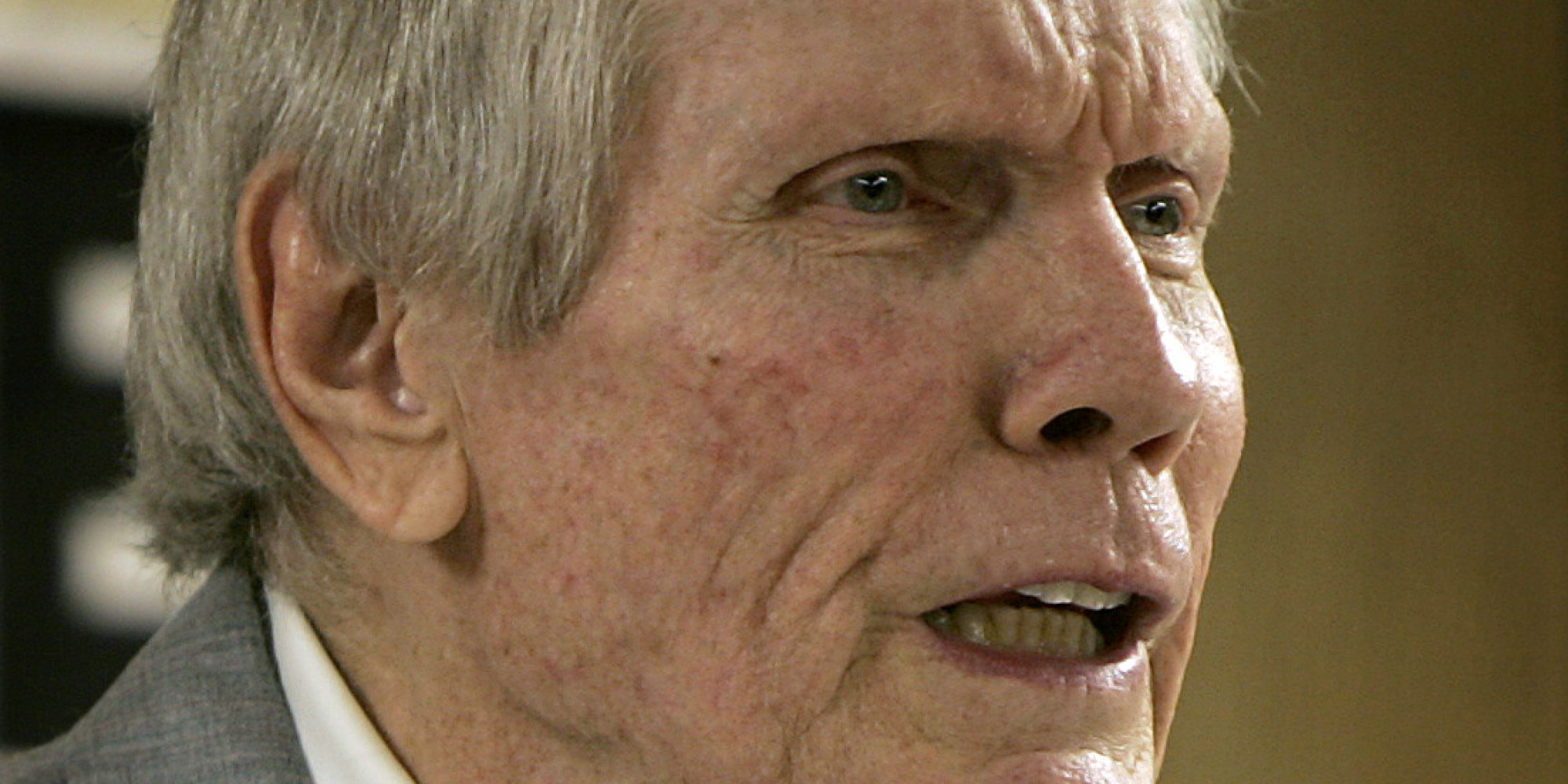

Jack Welch, a scurrilous American disease who was frequently misidentified as a human being, finally bit the bucket on Sunday. There are many business tycoons who will lionize this unapologetic ratfuck, but I, for one, am very glad that this unpardonable snollygoster, this vile enemy of the American worker, is dead. For Welch was an innovative corporate sociopath who prioritized profits over human life. He was known as “Neutron Jack” for a reason. It wasn’t just that he had the destructive force of a neutron bomb because of the callous way in which he destroyed the livelihoods of hard-working Americans for maximum gain. His very soulless demeanor resembled a weapon of mass destruction. If Fat Man and Little Boy could talk and carry on a board meeting, Jack Welch was the living embodiment of this murderous Faustian bargain. Jack tried to disguise his unrelenting evils with a phony smile and a bullshit avuncularism that was appealing to other white males who hoped to adopt and emulate his ruthless approach for their own ends. But make no mistake: for all of his candor, this scumbag was incapable of compassion and, as such, he deserves no respect.

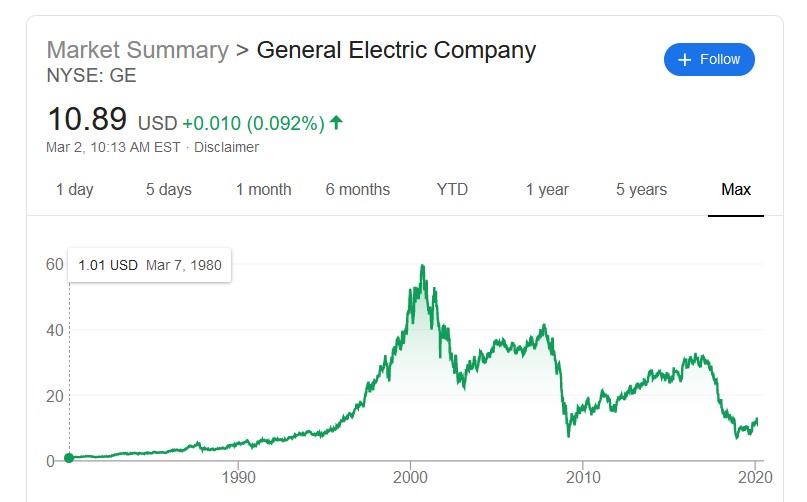

Welch’s fawning and uncritical acolytes claimed that everything he touched turned to gold. But at what cost? Welch was one of the first CEOs to break the covenant between a profitable company and the American worker. He believed in grouping workers into clusters — the so-called “vitality curve” — and not giving those who didn’t fall within the top 20% a chance, paying little heed or heart to human factors in a worker’s life that might temporarily alter their performance. Under his tenure at GE, he reduced 411,000 employees in 1980 to 299,000 employees in 1985. The GE stock kept shooting up during that time, rising to two and a half times the value. There was more than enough wiggle room to keep workers employed. But not for Jack. He sold off businesses and laid off workers and Forbes named him “Manager of the Century.”

But what was the end result of decimating GE like this? A swift rise followed by a sputtering fall. Because you can’t sustain this kind of growth forever. Under Welch’s handpicked successor, Jeff Immelt, it became very easy for GE Capital to become more cartoonish and thus flounder. And that is because Welch set the template for profit at any cost. It lines your pockets for a number of years, but it never lasts. And if that’s the case, are the many hundred thousand workers truly worth the sacrifice?

Jack Welch never gave a damn about the American worker or preserving job security. He was a dirty slithering hagfish who only existed to pursue mad and Machiavellian ends. In seven years, Welch not only reduced the GE workforce, but he reduced its unionized share. Unionized employees fell from 70% to 35% of the total workforce. This left them without the leverage to negotiate and they became targets under the vicious profit-motivated evil of Jack Welch.

There’s simply no way that anyone with a moral conscience can revere this guy. If you hold Jack Welch in any kind of esteem, then I don’t know if I could ever invite you to dinner. Before Jack Welch came along, there was a line in the sand in which it was understood that workers shared the profits and benefits of a company’s success. But Welch changed all that and inspired other lunatics to adopt similarly heartless policies that are now the norm. Welch only innovated in the way that he inflicted barbarism against this covenant with blue-collar Americans. And for that, his demise requires me to pop open a bottle of champagne and pledge a renewed commitment to standing up for the health, security, and wellbeing of the American worker as Jack Welch rots in hell.

Who knows how many beasts and wraiths Robin Williams confronted? One was too many. This was a terrible and needless loss that, irrespective of Williams’s talent and stature, demands that we take several steps back. We know that Williams was

Who knows how many beasts and wraiths Robin Williams confronted? One was too many. This was a terrible and needless loss that, irrespective of Williams’s talent and stature, demands that we take several steps back. We know that Williams was