- Over at Beatrice, Emily Gordon covers the New Yorker. J-Franz and J-Updike make cameo appearances.

- Laila Lalami meets Salman Rushdie and gets an unexpected surprise.

- John Leonard returns momentarily to the NYTBR to offer thoughts on James Agee (in our view, one of the finest film critics of the 20th century).

- More Banville interview to come over at Mark’s.

Month / September 2005

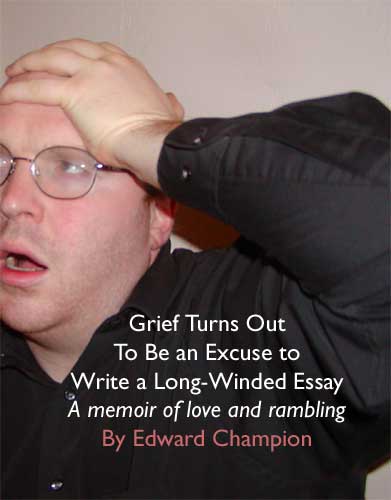

After Blog Life

1

Blog life changes fast.

Blog life changes more times than you can change your underwear.

You sit down to lunch and you know that there’s a blog awaiting you.

The question of pity parties.

Those were the first words I wrote after it happened. I had sent off yet another epistle to a media outlet. Mr. Tanenhaus’s assistant had personally telephoned me, telilng me that I was “chasing windmills” and that the New York Times office would no longer be accepting my brownie shipments. I can’t be sure about the dating on the Microsoft Word file (“Last-ditch olive branch letter to Sam Tanenhaus.doc,” I think it was called). I had long since deleted it and freed up that portion of my hard drive to download more porn. I sure as hell was’t Joan Didion, who clearly had more important things to say to the Gray Lady’s affluent and upper middle class demographic. I could sweat long and hard on a thoughtful essay about Gilbert Sorrentino or the interesting history of Soft Skull Press, but in the end if Didion wanted to write some 6,000 word essay on the sensation of putting two quarters into a soda machine, she’d have top priority and wouldn’t be edited at all. Never mind that I had suffered my own personal grief in 2005 and had used my sense of humor and perseverance to keep on writing.

For a long time I wrote haikus.

Blog life changes more times than you can change your underwear.

The ordinary underwear, not the expensive boxers I wear to give girlfriends smooth and easy access.

At some point, in the interest of remembering that letter, I decided not to allow myself to be crippled by morally complex decisions. Instead of laboring over a Word file, I wrote half a play, traded notes with a producer about a screenplay we were developing, banged out a lot of words on a novel-in-progress, began a literary podcast, and continued to blog profusely. All this with a full-time job. Like most writers, I didn’t have the luxury of a literary reputation to fall back on. I saw immediately that quibbling over the haikus was probably a bad idea, because, really, what good is there in laboring months over a sentence? I recognize now that there is nothing unusual in this, that most writers aren’t nearly high-profile enough to earn that particular advantage and that the Times was culpable in allowing a talented writer to take a colossal misstep, playing into the sympathies of a liberal elite that had very likely never known a day without a hot meal, much less stretched their hand across the class chasm to listen to and understand the very people they purported to support. Maybe back in 1966, when they were hungry and struggling and dealing with editors who would call them on their shit, these writers might be capable of stunning us with their amazing powers of observation; without exception, they had declined to do this for quite some time, never deigning to speak with the freaks and the bohemians and the dissidents and the crackheads and the troubled souls so regularly observed in my everyday life (but apparently not theirs) that the Sunday Times Magazine had so regularly ignored. Instead, they bankrolled top talent and suggested that they write about vacuity. They played into the whole essayist superstars mythos. And all this as the New York Times Company had laid off staff while silently pondering why the shares had dropped.

“And then — blogged.” In the midst of life we are surrounded by obsessions, and I had said this sentence one too many times. It had not been said by any philosopher of note. Later I realized that my rage at the newspapers, compounded by their deafness to my creative pitches, is what led me to become some febrile chronicler of literary motifs and happenings. Friends were kind enough to not tell me directly that I was chasing windmills, letting me find out for myself that such a regular plan was far from tenable. Never once did I exploit the intimate details of my personal life. All this without that bradykinetic yet pivotal period of thinking, of allowing dreams to unfold and wild ideas to transform into arguments and complex tales.

“And then — blogged.” In the midst of life we are surrounded by obsessions, and I had said this sentence one too many times. It had not been said by any philosopher of note. Later I realized that my rage at the newspapers, compounded by their deafness to my creative pitches, is what led me to become some febrile chronicler of literary motifs and happenings. Friends were kind enough to not tell me directly that I was chasing windmills, letting me find out for myself that such a regular plan was far from tenable. Never once did I exploit the intimate details of my personal life. All this without that bradykinetic yet pivotal period of thinking, of allowing dreams to unfold and wild ideas to transform into arguments and complex tales.

One thing’s for sure: there was never any hired help named Jose to pick up my mess. I cleaned my own toilet. I washed my own dishes. Every week, I picked up the detritus. And I never once asked my reading public to feel sorry for me through such a shameless publicity stunt: a desperate attempt to draw in more readers by headlining one individual’s personal misery.

2

August 23, 2005, a Tuesday.

I had ordered a large pizza.

I had seen the pizza advertised in a leaflet that had somehow been crammed into my mailbox and decided to give it a shot.

The pizza, with its pepperoni and mushrooms, would give me the strength to blog some more.

The pizza man arrived, I tipped him generously, I offered two slices to a friend and one to a homeless lady in my neighborhood.

All this, of course, is unimportant. But one must understand the exact contents in which the Tanenhaus letter was sent.

If the pizza could be said to have any feelings, I’m guessing it would have felt relieved yet somewhat homicidal as the pizza slicer partitioned it into eight pieces. If it could read, the pizza would probably be reading Sun Tze’s The Art of War, which is particularly sad, as the pizza itself was unarmed and had no appendages, much less a sentient mind, with which to attack its assailants.

The pizza was scarfed down by dawn.

Another one was ordered less than two weeks later. It was a pretty good idea, considering the untold burden of grief.

* * *

I used to have a large white dry erase board in my small rented room, for reasons having to do with a silly effort at appearing professional. Initially, I drew task lists for what I needed to do during any given week. But because the markers were colorful, I soon began drawing obscene pictures involving stick figures in flagrante delicto. I would invite friends to come by to play drunken games of Pictionary, carefully rationing the large bottle of Jim Beam that I had purchased on sale at a Safeway earlier in the year. I was using the dry erase board as a way to keep things going in light of the grief that threatened to destroy my routine.

I used to have a large white dry erase board in my small rented room, for reasons having to do with a silly effort at appearing professional. Initially, I drew task lists for what I needed to do during any given week. But because the markers were colorful, I soon began drawing obscene pictures involving stick figures in flagrante delicto. I would invite friends to come by to play drunken games of Pictionary, carefully rationing the large bottle of Jim Beam that I had purchased on sale at a Safeway earlier in the year. I was using the dry erase board as a way to keep things going in light of the grief that threatened to destroy my routine.

I sobbed as I scrawled those naughty pictures of stick figures. At the time, I wasn’t getting any and I had resorted to relentless masturbation to maintain my sangfroid. So should we all.

There was still no hired man named Jose who would help me balance my checkbook. I couldn’t afford such a man. Like most people, I had to sort this all out by myself.

But the dry erase board helped, even if it proved the wrong conduit for me to organize my life.

3

I had to believe that the grief could die. I had to believe that learning to laugh at the crazy world around us, without resorting to a long-winded personal essay, was the right road out.

I did lots of laughing in the months that followed. I’ve always done a lot of laughing. I’ve been kicked out of funeral homes for laughing. The fault, I suppose, is mine.

Yet.

I didn’t own a car and I slept on a futon. What kind of conditions were these for a man in his early thirties? Would things eventually happen for me because I had a pretty strong work ethic and produced who knows how many thousands of words? If there were any deficiencies in the way that I was approaching this, it was perhaps the simple fact that the things that interested me were quirky and alternative and not always highbrow. I had actually enjoyed The 40 Year Old Virgin! What was wrong with me?

Dale Carnegie, in How to Win Friends and Influence People, points out that the essential characteristic of winning people over is to dun your nose as you listen to a person of influence. Certainly, people interested me and I fancied myself a halfass listener. But why should anyone have to suffer fools gladly when one exists in either an imagined or a palpable sense of grief? Why should anyone reveal so many pedantic details to move newspapers? Shouldn’t some things be kept close to one’s chest? Shouldn’t more substantial things be written about?

The smell of sweet bullshit.

That was one way I could come to terms with this ethical conundrum.

I did not anticipate a midlife crisis at the age of 31.

SF Sightings: Tom Robbins

The Love Parade, the Blues Festival, Webzine 2005, antiwar protests, and that remarkably sunny weather that creeps into San Francisco during this time of the year didn’t stop about 250 people from gathering at the All Saints Church to listen to Tom Robbins read from his newest book, Wild Ducks Flying Backwards — an event sponsored by the Booksmith. The crowd consisted mostly of people in their twenties and early thirties, with a few hoary-haired holdouts that had somehow kept their humor and idiosynchratic faith while flaunting sartorial garb from the L.L. Bean catalog: no mean feat by anyone’s standards.

I had hoped to get Tom Robbins booked on the Bat Segundo Show, but while the people at Bantam were more than accommodating, it wasn’t in the cards. As Robbins himself explained to the crowd, he had recently had surgery in his right eye and had recently been the victim of “a Category 5 dental emergency.” This resulted in Robbins, at times, speaking out of the corner of his mouth. Robbins warned the audience that he “sounded like a cross between Gomer Pyle and Boy George.” Nevertheless, he still maintained the traces of his North Carolina drawl with a deadpan timbre, speaking at a measured pace and pausing to shout specific words into the mike for emphasis.

I had hoped to get Tom Robbins booked on the Bat Segundo Show, but while the people at Bantam were more than accommodating, it wasn’t in the cards. As Robbins himself explained to the crowd, he had recently had surgery in his right eye and had recently been the victim of “a Category 5 dental emergency.” This resulted in Robbins, at times, speaking out of the corner of his mouth. Robbins warned the audience that he “sounded like a cross between Gomer Pyle and Boy George.” Nevertheless, he still maintained the traces of his North Carolina drawl with a deadpan timbre, speaking at a measured pace and pausing to shout specific words into the mike for emphasis.

A few words on the new book: While the title shares the exuberance of Robbins’ previous tomes, this book collects short pieces that Robbins had racked up over the years. There are travel articles, “tributes” (more like over-the-top paeans, a few of them from 1967) to the likes of Ray Kroc, Nadja Salemo-Sonnenberg and redheads, an extremely mixed bag of “stories, poems and lyrics” (the less said about the poems, the better), “musings & critiques” and finally various responses to questions. In form, the book reminded me of Douglas Adams’ The Salmon of Doubt; the difference, of course, being that Robbins isn’t dead. While it’s a bit odd to experience Robbins in short form, causing one to reconfigure one’s head for unexpected ends (often after a mere paragraph), like The Salmon of Doubt, it’s still an interesting portal into Robbins’ thought processes. Just don’t pencil in the entire afternoon. You’re likely to knock this puppy off in a few hours.

Robbins was dressed in a grey suit that was slightly rumpled, although just crisp enough for a public appearance, and a black tee with the portrait of a cherubic green boy with crimson devil’s horns (the cultural connection momentarily eludes me). On his right hand, there was an extremely large and extremely round watch. He only took off his shades during the reading to reveal hounddog eyes surrounded by the deep circular recesses of age. But he kept the shades on during the Q&A session and, of course, during the mad rush of Robbinites stampeding towards the book signing line. He had dark tousled hair that appeared to have been cut by a barber in a rush. Near the back of his head, several sharp spikes emerged like blades of jet grass hankering for a head-shaped lawnmower.

Since we were in a church, Robbins started off by observing that his two grandfathers were Southern Baptists and that, because of this, he felt that it was his disposition to be in the pulpit. He said that he had spent some time in the Haight dring 1967 and remarked upon the many things to do in San Francisco. By comparison, Robbins noted that in his Northwestern town, there was little to do but throw a stick of margarine in the microwave and watch the oysters and clams come in from the fields.

He noted that despite San Francisco having “the highest cost of living in the solar system,” he was shocked that a bohemian culture still existed. This was, he thought, very conducive to art. And Robbins said that he had experienced a sudden burst of artistic activity. He had started writing a script entitled Pyrex of the Caribbean, which involved maintaining an oven-ready backing condition on the high seas. His offering for reality television was Fungi for the Straight Guy, whereby the producers would take a conservative Republican and give him a syphillitic mushroom with a camera crew following him around. And he had devised a pitch for a dramatic television show, Helen Keller: Private Eye with the tagline: “She’s blind, she’s deaf, she’s mute, but she can smell a rat a mile away.”

He read a piece first written in 1967, in which he had just seen the Doors. He read another piece from 1967 about the Seattle arts community. He read the Sonnenberg piece, as well as a travel piece called “Canyon of the Vaginas,” a story called “Moonlight Whoopie Cushion Sonata” and his response to the question “How do you feel about America?” in which the original response had been written in 1997 and updated with a footnote for the book. During the course of these readings, he would frequently stop midway, saying “And this goes on and on….”

Then there were questions. Robbins was asked what his favorite novel was. He said that Still-Life with Woodpecker was his favorite to write because it was so short. Half Asleep in Frog Pajamas, he found, “the structually most impressive.” Skinny Legs and All and Fierce Invalids Home from Hot Climates were “the ones I most admire,” although he said this with some uncertainty. Robbins doesn’t read his books after he’s written them. And this proved problematic when he had done several interviews in Italy. Unknowingly, Another Roadside Attraction had been republished. Unlike American journalists, Italian journalists actually read the book. So he was forced to respond to questions for a book he had not read in 25 years. He couldn’t obtain a copy of his own book, as the only ones available were in Italian.

An extremely obsessive Tom Robbins fan asked Robbins if Fierce Invalids from Hot Climates‘ Switters, seeing as how Switters appeared at the end of Villa Incognito, would be appearing in a future book. Robbins was clearly mystified by this and answered, “I haven’t been thinking about another book.” But he did mention that he was thinking of outsoucing the next book.

Robbins was asked which book he most admired this year. He said that he hadn’t been able to do much reading this year because of the eye. But he did say that the best books from the past 3-4 years were Louise Erdrich’s The Report on the Miracles at Little No Horse and Manil Suri’s The Death of Vichnu.

Questioned about his thoughts on the film version of Even Cowgirls Get the Blues, he said, “It was a big hit in Hungary.” He noted that Gus Van Sant was such a fan of the language that he had decided, against Robbins’ suggestions, to present the book’s dialogue as is. Robbins felt the film spiraled downward after the “first ten to twelve exhilirating minutes” and that, given the stylized nature of the language and that people don’t talk like this in real life, he felt it was a mistake that Van Sant had made that decision. Particularly since the first words were said by an actress who had never acted before. “Not a lot of authors will tell you that,” he said, mentioning that most novelists want to retain the original feel of a book.

Robbins doesn’t base any of his characters on real people, save Jitterbug Perfume‘s Dannyboy, who was “50% Timothy Leary.” However, the aforementioned Switters was based in part on a CIA agent Robbins had met in Singapore. Despite being a member of one of the most evil agencies in the world and despite desiring to be posted in Southeast Asia so that he could have sex with underage girls, Robbins remarked that this agent was articulate, well-educated, charming, funny, and the kind of guy who would risk his life for you. It demonstrated to Robbins that human beings were more complex than we give them credit for. Thus, Switters was born.

There was another minor character who Robbins had based on a real person — a yuppie he knew in “one of those books.” Apparently, a note from the editor came back, indicating that this one character didn’t seem real and was “too artificial.” But in this instance, Robbins had essentially taken the details from ordinary life.

Asked about Finnegans Wake, Robbins again insisted that he was stuck on page 49 and that he understands it all. He said that it was “the most realistic novel ever written” and said that it was almost impossible to be real in fiction.

Once, Robbins was on a panel with John Irving. And Irving had remarked that he could never write a book until he knew the end. Robbins couldn’t believe this and said, “Isn’t that like working in a factory?”

Since this is San Francisco, there was one question asked about what Robbins’ stance was on polyamory. Robbins genuinely did not know what this was. He confused it with polygamy. After an explanation, Robbins said, “I had some experience with that. I tell ya, it only can lead to disaster.”

Book Reviewers Wanted

Situation: There are more books here than I can possibly read. I would like to give all of these books a fair chance, given that the publishers have gone to great lengths to send them my way. But I am one person and, in order to exist in this world and have something of a life, it would be completely unrealistic for me to read them all. I can read three books a week, but not fifteen.

Now I am far from a trust fund kid, but here’s what I propose as a solution: If you would like to review these books that I cannot read, please drop me a line at ed @ edrants.com. Tell me a little bit about yourself and the authors you dig. And I will hook you up with a book that works within that template. I cannot pay you, but what I can do is offer my services as an editor and I can ship you the book. I’ll help you hone your voice and I’ll work with you to find a kickass tone. We can take a firm whack at these books that warrant coverage and, together, we can ensure that this heinous backlog is, to some small degree, abated. So what do you say?

The Ultimate Development in the Frey-Eggers “Best Writer of My Generation” Fiasco

Just when you thought that Oprah had confined herself to dead writers and the “Summer of Faulkner,” Oprah recently announced a return to living writers. Her first new book along these lines is actually quite interesting: James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces. I must confess that I’m highly amused at the idea of suburbanites in upstate New York and Orange County reading Frey’s gritty memoir. But if this represents the timbre of Oprah’s future offerings, then Return of the Reluctant strongly endorses the Oprah Book Club revival with the following proviso: No more Wally Lamb! Let’s see the Oprah Book Club dig up the kind of books that will provide a much needed jolt for soccer moms.