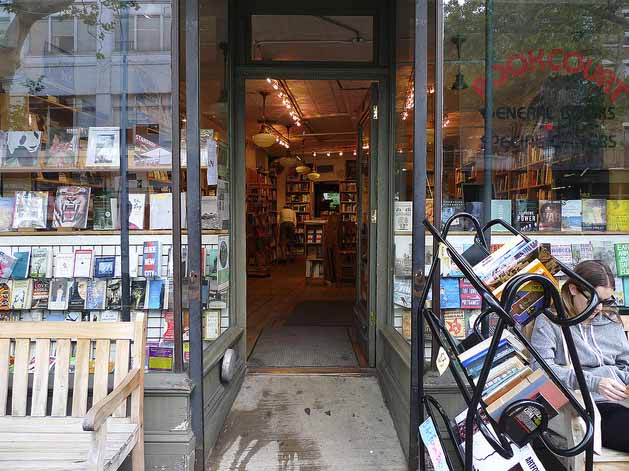

It was a humid Wednesday afternoon, and I was outside BookCourt with a microphone.

That morning, a New York Times story about paid author events ignited a firestorm on Twitter. Some independent bookstores, hurting for cash, were now charging admission for a reading. Sometimes it was as little as $5. Sometimes it was the price of the hardcover for an off-site event. What had once been free was now the cost of a pint at happy hour.

These developments began in April. In Colorado, Boulder Book Store announced that it would charge $5 a head to attend an event. In California, Kepler’s demanded a $10 gift card to admit two people through the new paywall.

Was this reasonable? Or was this a form of gouging? Wasn’t the purpose of an author event to give the customer a chance to sample the goods? And would such a practice, as Ann Patchett suggested, scare off those who didn’t have the clams for a hardcover?

And why had nobody talked to the customers about this?

The time had come to sweat in the sun and ask every person leaving BookCourt to take part in “a journalistic survey.” I talked to as many customers as I could before the next thunderstorm broke. Some people were skeptical. Others were kind, but in a rush. One woman ran away, calling me “one of those goddam bums.” (In my haste, I had forgotten to shave and I was wearing an old T-shirt.) But most were accommodating.

Listening to the Customers

During the afternoon of June 22, 2011, we conducted several interviews with book customers outside Bookcourt for this story. Listen to Glenn Kenny discuss his thoughts on author events with Our Correspondent. (3:27)

Lucas, a smiling 50-year-old man who doesn’t work, told me that he doesn’t really attend author events, but that he “bumps into them.” He said he wouldn’t pay for an author event, largely because he views it as a meeting. In his view, the reader shouldn’t pay to meet people. “It’s very bizarre to go to an author meeting or gathering. Because basically you meet authors through their books. So I read their books. And I sort of dream about meeting them. But I don’t really want to meet them.”

Miriam, a 35-year-old consultant, told me she attended two to three author events a year. She likes “to learn about the work that goes behind the writing.” Asking stimulating questions and “the author’s voice” were also big draws. She said that she would pay $5 for an author event “if it was an author I liked.” The $5 fee wouldn’t make a huge difference, but she felt that “these things should be free to get the maximum number of people.” Miriam said that, if she were intrigued, she would pay for a debut or an unknown author event. But the biggest reason that Miriam went to events was knowing the author in question.

Patty Greenberg, a 60-year-old stay-at-home mom tightly gripping the leash of a rather large and very well-groomed poodle, told me that she only attended one author event a year and that she would only pay $5 if she was really interested in the author.

A 24-year-old dancer who claimed to be “Devon Alberta” (stage name or lark?) said that he doesn’t attend author events, but that he would pay money “if he liked the author.” He would even purchase the book if this was the cost to attend. Why does he attend author events? “I always like to have access to the writer and the way that they communicate outside of the text.”

Then there was an unexpected run-in with the film critic Glen Kenny, who told me that he attended five author events a year. Would he pay? “Five dollars is about reasonable if I wanted to go. And if there was seating.” Kenny confessed that he mostly goes to events if he knows the author, but he is interested in the presentation. “Just a window into his own perception of what he’s doing, I think, is often conveyed through reading.” He pointed to key differences between seeing Martin Amis at an event when he wasn’t well-known versus when he was well-known. But he did admit that an author event “doesn’t necessarily enhance my appreciation of the work.”

Brandon Pederson, a 24-year-old gentleman who identified himself as “a real-time highlighter for Major League Baseball,” said that he usually attended four author events a year. He said he would pay $5 if he “was sold on them being someone I would give $5 to” — note the way Pederson views the money as going to the author, not the bookstore. Pederson said that he often attended author events because “friends told him to.” I suggested to Pederson that surely he had free will. He then told me that he was new to the city and interested in “theory” and “fiction that pushes what fiction is.” He enjoyed hearing authors talk about books, sometimes buying them to be signed. But if Pederson was asked to pay $5 for an author he hadn’t heard of, then his criteria changed: “if the work sounded relative to what I was interested in.”

Jen, a 27-year-old teacher, told me that she probably hadn’t been to an author event at a bookstore. She was fond of going to author lectures –“usually authors that we’re reading about and stuff that we’re taking excerpts from.” Why did she avoid bookstore events? “Honestly? Probably because it’s not marketed that well. I don’t know about them.” Jen said that she would pay for an author event at a bookstore, but, like the majority of the people I spoke with, it would depend on who the author is. She would pay for favorite authors, but she wouldn’t pay for debut or unknown authors. “Not unless it was a friend I was trying to help out.”

Another 27-year-old teacher named Lynn, accompanied by a highly animated dog, was an even bigger fan of author events than Jen, in large part because she teaches English. She copped to attending 40 author events a year and she was the only person I talked with who had read the New York Times article. Why did she attend author events? “I’m bad in bars.”

While paying for an event would make her think twice, Lynn said that, despite her teacher’s salary, she would pay $5 if she had to because she loved independent bookstores and wanted to see them flourish. “There’s a reason I don’t buy used books.” But she did say that her husband would probably give her a hard time if she was forced to pay out $200/year.

Lynn told me that she had been disappointed by some author events. “I just go to go. It would have to be more of a schtick. Some do interviews. And some just read. I might be a little more thoughtful about the events that I go to.” I asked if she would want more from a reading if she was ponying up a Lincoln. “Yeah,” said Lynn. “Instead of Paul Auster reading, Jonathan Lethem interviewing Paul Auster. Maybe there’s wine and cheese.” Like other paid author event supporters I talked with, Lynn said that she would have to be somewhat familiar with a debut or unknown author to attend a paid author event — perhaps through a story in The New Yorker or One Story.

Will Paid Author Events Create More Demands?

“Instead of Paul Auster reading, Jonathan Lethem interviewing Paul Auster. Maybe there’s wine and cheese.” Listen to Lynn, a 27-year-old schoolteacher, discuss her thoughts on paid author events with Our Correspondent. (1:59)

Doug Stone, a 40-year-old writer, said that he attended somewhere between three and four author events a year. Asked if he would pay $5 for an author event, he replied, “Well, it can’t be anybody.” Stone said that readings had a certain feel of inclusiveness that might be diminished by asking people to pay. “I’ve been to bookstores where you’re browsing and you didn’t even know there was going to be a reading. Then all of a sudden, we’re doing a reading. And you go over and you’re introduced to people.” He felt that charging money changed the spirit of the event and audience expectations. “The readings that I’ve enjoyed the most, they’re just a free event.” But Stone was not averse to someone passing the hat after an author event, if certain needs were stated. “I would put ten frigging dollars in that hat.”

What do these conversations tell us? It reveals that people like Lucas and Doug Stone often attend author events when it is random and that these happy accidents can produce potential acolytes. Nearly all of these customers see the author event as an experience to get to know the author beyond the book. Attending an event represents a perceived social experience. A $5 fee not only created the distinct possibility that debut, experimental, and unknown authors would be cut out of the loop, but it created new demands upon authors and bookstores. Would authors be required to perform? Should the authors be compensated? Would the audience demand more?

“Paid author events are common in Europe,” says novelist Stewart O’Nan. “In fact, a free author event would be uncommon, and even those are subsidized by the publishers and bookstores in co-op fashion, with the author being paid for each and every tour appearance. Because the author, when not writing, is being asked to be a performing artist. What other professional would be asked to travel across the country and perform their work for free? Even the lowliest dive bar has to give the band half of the door. This ain’t open mike night. The store provides the venue & the advertising & logistics, so they should definitely get a cut, but the author, being the attraction, should definitely be compensated.”

“Author events are a kind of gentlemen’s agreement, in a way,” says memoirist Alison Bechdel, who also offered an idea of authors performing foot massages for a small fee and splitting the take with the bookstore. “It’s understood that the bookstore and the author and the publisher all have a stake and a responsibility, but it’s a complex, overlapping mix in which you all depend on one another and work as hard as you can to have a successful event. All three parties want to sell the book. But there are other, less commodifiable, elements in the mix. It’s worth something to readers to have access to an author. It’s worth something to authors to have the opportunity to reach readers. It’s worth something to bookstores to get traffic and possible new customers. And when, inevitably, there’s an event that no one shows up to, the toll is not just financial — it’s depressing.

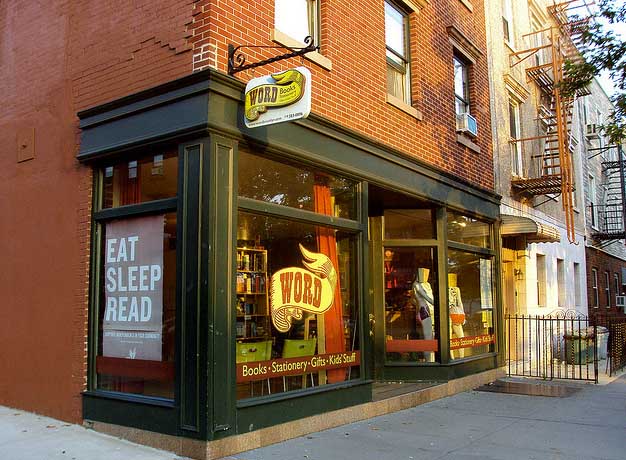

Stephanie Anderson, manager of the independent bookstore WORD Brooklyn, concludes that the author is being compensated on some level. “We’ve definitely noticed a strong correlation between how much an author and audience connect and how many books sell. I know royalties aren’t huge, but they are a good reason to want to sell a lot of your own book.”

I reached Tayari Jones by telephone as she was in the middle of a very involved indie-friendly tour for her latest novel, Silver Sparrow. Jones said that she was very grateful to the independents for their support of her book and that she wanted to do whatever she could for them. But she did express some reservations about paid author events could solve present problems.

“We need to raise awareness,” said Jones. “But I think that charging money feels punitive.”

Jones brought up a hypothetical example of a customer driving all the way from Detroit to an Ann Arbor bookstore and being turned away because she didn’t have the $5. “Can you imagine that?” Jones said that she didn’t want anybody turned away. Would this mean authors and publishers subsidizing author events for those facing financial hardship? I asked Jones if she would pay out of pocket. “$100,” said Jones. “I could front twenty people.”

Jones has adopted one strategy of informing her audience why it’s important to purchase a book at an indie — even if members of her audience have already done so. “It’s worked every time.” She notes that when such a request comes from the author (instead of the bookseller), it tends to have a less partial perception.

“My bottom line is this,” says novelist Jennifer Weiner. “I don’t think authors have any business telling readers where or when to buy their books. Would I love it if everyone bought my new hardcover the day it was published at Headhouse Books, which is my neighborhood independent in Philadelphia? Absolutely. Do I understand if they’ve got e-readers, or can find the books more cheaply at Sam’s Club or Target, or wait for the paperback, or visit the library because a hardcover isn’t in their budget? Absolutely. I’m grateful to have people reading my books, however and whenever they do it.”

Weiner hopes that struggling independent booksellers can consider the long-term customer. “Maybe the graduate student or young mom who shows up at my reading isn’t going to drop $27 on my newest hardcover, but maybe she will buy a trade paperback, and a few Judy Moodys for her kid. So the store’s making money, even if it’s not on my book. Or the putative reader won’t buy the book that day, but she’ll get it in two weeks. Or she won’t get it at all, but she’ll tell a friend, who will then buy a copy.”

Still, as former bookstore marketing manager Colleen Lindsay has observed, the author event is fraught with significant costs, including expenditures for returned books and those customers who couldn’t purchase a book that they wanted.

Off-site events, such as WORD Brooklyn’s recent ticketed event with China Mieville, have made a difference. “I think ticketing the event and having the vast majority of the books pre-purchased ended up making the event a better one overall,” says Anderson. “We and the venue were able to properly plan because we knew how many people were coming, which made setting up and transitioning from Mieville’s interview to his signing much easier (and meant he could spend more time with fans). It also meant that the act of commerce was essentially disassociated from the event, because everyone had already paid. There was no pressure to buy, because everyone had already bought. The staff could spend more time talking with people and helping out, instead of running a million credit cards. We did have some backlist titles available for sale and sold a few, but most people just got right in line with the book they had gotten when they walked in the door, and it all went very smoothly.”

Yet O’Nan suggests that shifting to a pay-for-play model generates additional problems of writers competing with celebrity writers. “Sarah Palin will sell a truckload more books and draw much bigger crowds than, say, Tom Wolfe,” says O’Nan, “who will sell a truckload more books and draw a much bigger crowd than, say, Steven Millhauser. In the end, is the idea merely to turn out the largest crowd and make the largest profit (and to sell the largest number of copies)? If so, book Sarah Palin. If it’s to enjoy the genius of a master storyteller, call Steven Millhauser. I’ll pay good money to see him.”

“There many be some evolution towards a revenue share model similar to what you see at a music venue, where they book in an act and share the door with the performer,” says Christin Evans, co-owner of The Booksmith in San Francisco. “We’d be open to considering that type of model. We already have a similar arrangement with the performer as our monthly adult cabaret event, The Literary Clown Foolery.”

Jones, O’Nan, and Weiner all tell me that they work very hard at their author events.

“I bring an A-game regardless,” says Jones. “There could be no more additional pressure.”

“I go out and give my all every time, whether I’m being paid decent money at a big university or reading for free at a tiny library,” says O’Nan.

“My secret weapon is baked goods,” says Weiner.

But do performance elements — what the dedicated bookstore customer might call “schtick” — create new demands for authors and bookstores in the 21st century?

Glenn Kenny suggests that some of these performance elements have been there all along. “I remember going to benefit events,” says Kenny, “which combined readings with music. It was something that McSweeney’s did after 9/11 at Angel Orensanz that had Chuck Klosterman reading from Fargo Rock City and David Byrne doing a PowerPoint presentation. So those things, which are packaged like entertainment events, they make more sense to be paid events, per se. But a plain reading might not necessarily be it. But I can’t rule anything out.”

While Weiner says that she would pay considerably more than $5 to listen to author Jen Lancaster, which she compares to “attending a stand-up performance,” author events can sometimes work in reverse.

“Some authors just aren’t very good at the performance component of this job,” says Weiner. “Which doesn’t mean they’re bad writers. It just means that maybe they aren’t necessarily the ones publishers and bookstores should send on the road and make readers pay to hear. And yes, there is something a little off-putting about charging for an event and the author, and her publisher, and whoever interviewed her if it was a Q and A, not seeing a cent of the money, particularly since publishers are the ones who pay to send authors on the road. I can see that independent bookstores feel like they need to take a ‘by any means necessary’ approach to cultivating revenue streams, but maybe there’s an approach where a bookstore could say, ‘If we clear more than X dollars that night, we’ll split the cost of the author’s plane ticket and hotel stay with her publisher.’ And anyone who volunteers his or her time to interview an author should at the very least get a gift card, or a few books for their trouble.”

It remains to be seen if paid author events will become a new regular fixture at this early stage in the game. In the meantime, some authors simply hope to go on with their business.

“The road of thinking that what we do is simply quantifiable — my ‘words’ or my ‘appearance’ having some fixed value — is the path of madness,” says Jonathan Lethem. “I’m just glad that anyone cares at all to either read the work or come catch a glimpse of me, and anything a bookstore can do to go on being a bookstore is just fine with me.”

“Everything is an experiment in the book business,” says Sherman Alexie. “We are talking about writers and independent booksellers. We are not talking about economic geniuses. We are all flailing.”

(Images: Rebecca Williamson, Daniel Huggard, bitchcakesny, Steve Rhodes)

Now ACWLP is a bookstore that Your Correspondent doesn’t frequent nearly as much as he should, in large part because Your Correspondent is somewhat vexed by the sizable contingent of smug and excessively coiffed and (most of all) humorless folks found in that area. No fault of the amicable ACLWP people, I assure you. You can find this contingent in

Now ACWLP is a bookstore that Your Correspondent doesn’t frequent nearly as much as he should, in large part because Your Correspondent is somewhat vexed by the sizable contingent of smug and excessively coiffed and (most of all) humorless folks found in that area. No fault of the amicable ACLWP people, I assure you. You can find this contingent in

I had hoped to get Tom Robbins booked on the Bat Segundo Show, but while the people at Bantam were more than accommodating, it wasn’t in the cards. As Robbins himself explained to the crowd, he had recently had surgery in his right eye and had recently been the victim of “a Category 5 dental emergency.” This resulted in Robbins, at times, speaking out of the corner of his mouth. Robbins warned the audience that he “sounded like a cross between Gomer Pyle and Boy George.” Nevertheless, he still maintained the traces of his North Carolina drawl with a deadpan timbre, speaking at a measured pace and pausing to shout specific words into the mike for emphasis.

I had hoped to get Tom Robbins booked on the Bat Segundo Show, but while the people at Bantam were more than accommodating, it wasn’t in the cards. As Robbins himself explained to the crowd, he had recently had surgery in his right eye and had recently been the victim of “a Category 5 dental emergency.” This resulted in Robbins, at times, speaking out of the corner of his mouth. Robbins warned the audience that he “sounded like a cross between Gomer Pyle and Boy George.” Nevertheless, he still maintained the traces of his North Carolina drawl with a deadpan timbre, speaking at a measured pace and pausing to shout specific words into the mike for emphasis.

But he?s also a lively conversationalist and a true raconteur. His comments were leavened with humor: ?These guys [Bush and Cheney] have turned me into creationists?Darwin was wrong!? And of course, it?s hard to imagine anyone else who knows so much about US history. His faculties remain undiminished by the fact he?ll turn 80 this year or that he now walks haltingly with the aid of a cane (he recently had knee surgery). He speaks in a deep baritone and, while regaling the packed house with his inexhaustible supply of anecdotes, treated us to spot-on imitations of JFK, Eleanor Roosevelt, FDR, Orson Welles and W (natch).

But he?s also a lively conversationalist and a true raconteur. His comments were leavened with humor: ?These guys [Bush and Cheney] have turned me into creationists?Darwin was wrong!? And of course, it?s hard to imagine anyone else who knows so much about US history. His faculties remain undiminished by the fact he?ll turn 80 this year or that he now walks haltingly with the aid of a cane (he recently had knee surgery). He speaks in a deep baritone and, while regaling the packed house with his inexhaustible supply of anecdotes, treated us to spot-on imitations of JFK, Eleanor Roosevelt, FDR, Orson Welles and W (natch).