Love and Sex with Robots

Love and Sex with Robots

David Levy

HarperCollins, 334 pages, $24.95

Review by Erin O’Brien

Let’s start with the RealDolls.

Actually, it’s not the dolls I want to dwell on, but the men who own them. I spent untold hours conversing on an online forum set up specifically for sex doll owners while researching this article. The human aspect of the sex doll fetish/hobby has stuck with me ever since that piece ran almost a year ago. The love doll phenomenon might seem banal at first blush, but I found it to be complex and surprising at every turn.

Sex is the most popular doll activity, but owners also dress the dolls, talk to them, kiss them, and purchase lingerie and perfume for them. They pose and photograph the dolls. They name them and often imbue them with fantasy personalities. Some men even present themselves on The Doll Forum as their doll. As I struggled to understand it all, one of the forum members asked me if I love my car. That stopped me. My Mini Cooper is compact and responsive and never takes more than it needs. I want to emulate it at every turn. Do I love it? I practically deify it. And it’s not the only object that is more to me than the sum of its parts. My iPod is not only a jewel, but also a valued companion on my endless walks. I am free to enjoy those affairs without fear of persecution, but the rules are different for men who enjoy love dolls. Most owners are terrified of being outed.

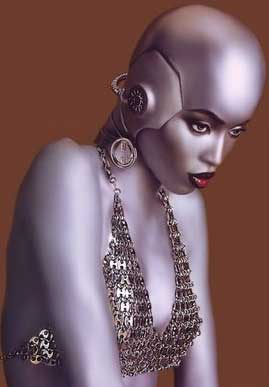

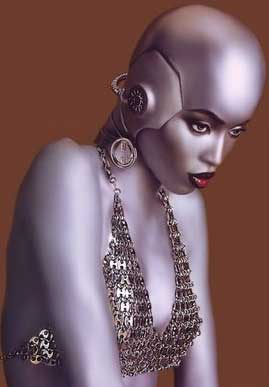

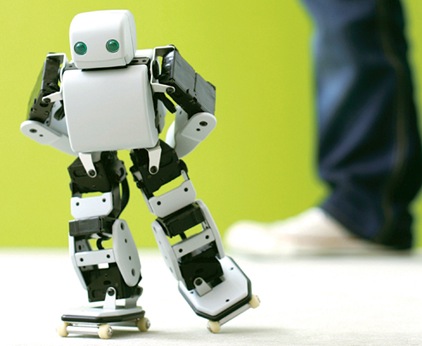

Doll owners constantly discuss advances in doll technology. They want convenience features such as removable sex organs that can be easily cleaned but stay put during critical moments. They want their dolls to talk and move. They pine for fully functional “gynoids” that they can be programmed to accommodate any sexual proclivity. Forum discussions wax and wane with excitement and disappointment, depending upon how close technology is to making their dreams come true. While on the forum, doll owners evoked my sympathy, empathy and antipathy — as well as my fascination. So when I heard about David Levy’s book Love and Sex with Robots, it piqued my interest.

“Accepting that huge technological advances will be achieved by around 2050,” claims Levy in the book’s introduction, ” … Love and sex with robots on a grand scale is inevitable.”

From day one, my world was filled with technology. My father designed and built machinery. My degree is in electrical engineering. I respect milling machines, I remember the Radio Shack TRS-80 computer, and I consider my laptop to be an attractive accessory that complements who I am. I agreed with Levy’s assertions about our advances in AI and computer technology. And yes, the human fascination with automata is boundless. It starts early too. Every kid is transfixed by a window display of animated Christmas elves no matter how repetitive and mechanical their movement. I know I was. I still am.

From this starting point and through three hundred odd pages of text, Levy’s premise could surely convince me to fall in love — and maybe even marry — a robot.

I’m just a love machine

Early in the book, Levy says he will not detail the mechanics behind the robot frontier. This immediately felt like a cheat to me and put a big chink in Levy’s credibility. The emulation of the human hand, lips, and tongue seem like important components to address when pondering lovebot technology. Yet Levy does not address such issues. No matter how hard I tried, the cunning engineer in me couldn’t stop worrying about design. A lovebot will require a heating system. (RealDoll owners often use an electric blanket.) Will the user manually lubricate the robot for sex or will it have a system with refillable reservoirs? Something along the lines of windshield washer fluid? That robot kid in AI got bested by a mouthful of spinach, but he did fine even after he fell in a pool. This is more than I can say about my cell phone. I eat a falafel sandwich to stay powered up. What will fuel a lovebot? How long will the rechargeable battery last? Coitus interruptus because of a drained battery would be a real drag. Sort of like having to put your cool road trip on hold for a few hours in Shamrock, Texas while the electric car juices up.

These mystifying “huge technological advances” didn’t sit well with the Los Angeles Times‘s Seth Lloyd either.

Lloyd brought his own credentials (quantum-mechanical engineering professor at MIT) to the intrinsic problems of programming computerized robots to perform even the humblest of tasks. He calls Levy on forecasting developments so far in the future that no one can refute them, calling such extrapolation a “mug’s game.” And make sure you dig his comments on Levy’s lack of literary references. Remember Data in Star Trek: The Next Generation? We thought R2D2 was adorable. And everyone drooled over Cherry 2000. Levy doesn’t mention any of them. Not even Jude Law’s silken Gigolo Joe, who would seem to embody Levy’s vision.

Levy also forecasts that lovebots will cost the equivalent of two C-notes by the middle of the century. Right now, $199 will buy you an iRobot Roomba Robot Vacuum at Target, but the only thing it sucks is dust bunnies and pet hair. Sure, the Roomba may go down in price. Electronics generally do. Mechanical devices do not. Build them cheap and, well, is anybody out there still driving a Yugo?

You make me feel like a natural woman

From Sex and Love with Robots:

Anyone who has doubts that women will find it appealing or even possible to receive the most incredible, amazing, fantastic orgasms, courtesy of sexual robots, should think again. Think vibrators.

Did someone say vibrator?

The Cone Vibrator boasts 16 settings courtesy of a 3,000-rpm motor and is fueled by three C-sized batteries. The smooth medical-grade silicone surface is easy to clean and comfortable to (ahem) interact with. And believe me, set this baby in the center of the bed and it stays put no matter how enthusiastic that interaction gets. It costs about a hundred bucks.

Purrr.

I love my ridiculous toys. But the idea of a life-sized male sex doll does nothing for me. Sure, a toy delivers satisfaction. But it is just a toy. It has nothing to do with men or lovemaking. (Well, maybe as an accessory. I mean, insinuate yourself on the cone and your entire upper body is free to … um … oh, never mind.)

Why? It has to do with the essence of our subtle physiological yin and yang: that swirling vortex wherein you find the quest for a woman’s climax, fear of impotence, a lover’s thrill at the sight of a swelling erection on a man he or she wishes to arouse and the sense of failure a flaccid member evokes in the same situation. The lie of a woman’s faked orgasm and the intensity of pleasure between two people exchanging undiluted desire.

That said, the vagina has more wiggle room than the penis. Erica Jong called the fairer genitalia an “all-weather” organ, suitable for use anytime as long as a bottle of lubricant is in arm’s reach. The passive nature of the vagina makes it easier for a heterosexual man to suspend disbelief and engage in activities such as prostitution and doll play. Not so with the penis. The Viagra discussion notwithstanding, arousal must produce a man’s erection, which silently proclaims, you are sexy and desirable to me. It is an honest organic response, not the proper execution of computer programming. An erection imparts affirmation that a phallus will never evoke.

That said, the vagina has more wiggle room than the penis. Erica Jong called the fairer genitalia an “all-weather” organ, suitable for use anytime as long as a bottle of lubricant is in arm’s reach. The passive nature of the vagina makes it easier for a heterosexual man to suspend disbelief and engage in activities such as prostitution and doll play. Not so with the penis. The Viagra discussion notwithstanding, arousal must produce a man’s erection, which silently proclaims, you are sexy and desirable to me. It is an honest organic response, not the proper execution of computer programming. An erection imparts affirmation that a phallus will never evoke.

As a heterosexual woman, I don’t think I’m alone in my indifference to the male sex robots of the future or the male dolls of today, but I’m not sure. Although Abyss, the manufacturer of RealDoll, sent me droves of info when I asked about their product, they didn’t respond to my numerous queries about how many “Charlie” male dolls they’ve sold. I’ve read that it’s only about a dozen.

Levy is completely at odds with this topic. In one sentence he proclaims that vibrator love means robot love. In the next breath, he admits that, unlike men, women do not buy love dolls.

Why not? Although breadwinning men with gleaming teeth and pompadours stiff with Brylcreem can have their RealDolls and eat them too, the cake of Levy’s argument asserts that women probably just can’t afford “Charlie” at $7,000. He admits that this probably isn’t the only reason, but it’s the only one he cites.

An angry red blush bloomed on my neck as I digested this factoid, but I must agree: $7,000 is a lot of money to pay for the privilege of lying beneath 100 pounds of inert silicone.

I suppose I could sit on top of it.

Nah.

They’ll never get that perfect spot where shaft meets torso right. Besides that, Charlie wouldn’t fit in the box under my bed.

Even the losers

Levy is a savvy proselytizer. He appeared on the January 17 episode of The Colbert Report. When asked why people would want a lovebot, he said, “The most common reason I think at the beginning will be that there are millions of people out there in the world who for one reason or another can’t establish normal relationships with humans. They’re lonely, they’re miserable and robots, when they’re sophisticated enough, will be an excellent alternative.” When Colbert asked him if he would ever have interest in a robot, Levy responded, “No … this is for the other people.”

Okay folks, queue forms on the right. You lonely miserables–raise your hands. You guys head straight up front. The ugly guys are next. No, no. No need for you dogheads to raise your hands. We can see who you are. Just get behind the miserables. When all the pathetic losers are settled, the rest of you normal, middle-class, right-as-rain Other People have at it. As soon as I blow the whistle, let the stampede begin.

When a writer distances himself from his topic, he risks insulting his material as well as his reader. This is particularly relevant when writing about sex. If you don’t put yourself on the playing field either directly or indirectly, you come across as judgmental. To get on that field, you must put forth your assertions in the context of your reader and yourself. That is vulnerable territory–upon which Levy dares not to tread. Instead he relies heavily on studies and history in order to broach his topic. His research is thorough and interesting. Unfortunately, too often it looks backward and not forward. Catastrophically, it never looks inward.

Levy cites our pets, our Internet romances and our ongoing love affair with electronic equipment as examples of alternative human affections. So because I love my cats, I’ll marry a machine? And, yes, I have a complex relationship with my computer, but it serves mostly as a tool and a vital connection to other people. That argument led me nowhere. It’s true that people have online affairs, but in the end, it’s still something conducted in the flesh between two people.

This was the absolute scientific fact that proves humans will soon universally love and marry robots? I was still miles away.

A humanoid robot that is programmed to perform its owner’s specific wishes sounded like a new-fangled way to say hooker, trophy wife, or sex slave. The more sophisticated the electronic entity, the more cruel the electronic leash. I couldn’t see it any other way.

What I needed was a deep thought.

But it’s all in the game

Levy is an international chess champion and the author of dozens of books on artificial intelligence and computer gaming. His passion for his subject is evidenced by a long list of international credentials concerning those topics. He led a team to win the 1997 Loebner Prize (world championship for conversational computer software) and is currently the president of the International Computer Games Association. In 1968, Levi wagered that no computer would beat him at chess within the next ten years. He won that bet against his fellow AI aficionados, which garnered him considerable notability. Eleven years later, however, he was defeated by the computer program “Deep Thought,” which leads me to the heart of the trouble with Love and Sex with Robots.

Levy is an international chess champion and the author of dozens of books on artificial intelligence and computer gaming. His passion for his subject is evidenced by a long list of international credentials concerning those topics. He led a team to win the 1997 Loebner Prize (world championship for conversational computer software) and is currently the president of the International Computer Games Association. In 1968, Levi wagered that no computer would beat him at chess within the next ten years. He won that bet against his fellow AI aficionados, which garnered him considerable notability. Eleven years later, however, he was defeated by the computer program “Deep Thought,” which leads me to the heart of the trouble with Love and Sex with Robots.

This book is a commercialized version of Levy’s academic paper on the topic, for which he earned a Ph.D. The resulting scientific detachment about subjects that are not scientific–love and sex–is problematic. Although Levy’s passages about the histories of vibrators and sexdolls are wonderful, you won’t find one candid breath about the human beings behind them.

Love and Sex with Robots is screaming for eye-blinking moments such as an anecdote that a doll owner conveyed to me: he loved painting portraits but no model was patient enough for him. “A life-like doll seemed the ideal solution,” he said. “However, when she arrived, I was so taken with her realism that I automatically became fond of her.” And in an instant, this would-be Pygmalion instilled gentle poetry upon the idea of man and doll, which no longer seemed so strange.

That is how a writer must normalize a sexual subculture, by evoking the reader’s empathy over his sympathy. Exclude the anecdotal details and the droning research ends up sounding like the teacher in a Peanuts cartoon.

Levy didn’t have to go very far to find a humanizing facet for his subject. All he had to do was step from behind the scientific mask for a moment and describe his lifelong fascination with AI. I smoldered with curiosity about the tipping-point moment when he knew “Deep Thought” had the game in 1989. How did he feel? I imagine it was a thrilling culmination of anger, hatred, respect, frustration, admiration and humility–a stinging slap from a beautiful woman. Perhaps it was arousing as well as infuriating. Such disclosure would have increased the power of this book ten-fold.

But the future lovebots Levy depicts are no Deep Thought femme fatales. They are submissive Stepford Wives for the masses, programmed to meet their owner’s every whim. When I juxtaposed McRobot against the brilliant Deep Thought entity that defeated a genius, it amounted to a subcontextual insult. How would Levy respond if asked to check off the box on the order form that indicated whether he’d like his custom-built robot to let him win at chess (a) always, (b) once in a while, or (c) never?

Perhaps such pedestrian options are for the “other people.”

Electric slide

Levy devotes 27 pages to “Why people pay for sex” whereby he quietly admits that buying a mechanical companion is akin to prostitution. To his credit, there is no hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold or Pretty Woman moment. The section about why women pay for sex is one of the weakest in the book. A tidbit involving ten female johns that Levy cites from a February 1994 article of Marie Claire (UK) does little to normalize the idea of paying a man to share a bed. The johns discuss their lack of success with men, the freedom from complications and constraints that inundates relationships, and the need for companionship they cannot fulfill otherwise. He concludes the chapter by saying paid sex “can be a positive experience even though [the johns] know that their sex object has no genuine feelings of affection for them.”

I wanted to make sense of all this. So I reviewed AI while writing this essay. I watched Gigolo Joe’s love scene again and again. Who is this scene for? The woman is a teary middle-aged cliché. People with complex sexual troubles surely do not see themselves this way. They don’t need pity; they need a solution. It’s not Gigolo Joe, who is more contrived than his human counterpart. Paying for sex doesn’t make sense to most women, which is why the call for heterosexual male prostitutes is a barely audible peep. Gigolo Joe’s mechanical hard-on is a lie as well.

I detest the isn’t-it-wonderful-that-these-sad-people-have-this-option-available-to-them shtick, but that’s all Levy offers me here. Again, I needed a quotidian inroads, such as the heterosexual fiftysomething man in a strapless evening gown I discovered when conducting research for a feature on cross-dressing. “Glenda” told me that, when she leaves Glen’s rough work clothes behind and steps out in pantyhose and heels, the world treats her differently — even if she’s not all that convincing in her role. Glenda can also leave Glen’s troubles behind, such as the grief surrounding his 19-year-old daughter’s suicide.

Oh.

But at one point, Levy finally grabbed me. He chronicles the efforts of the Erotic Computation Group at MIT, which endeavors to explore modern computing, human sexuality and sex toys of the future. I sat up in attention, only to read the next paragraph, wherein Levy reveals that the group was a hoax, and was gravely disappointed.

Love and Sex with Robots represents a massive amount of work. But it fails to reveal a profound truth — something I believe is still waiting to be uncovered. I wish Levy had included some of his own secrets and desires. I wish he had gotten his hands dirty and talked to real people about real sex and fetishes. But the galvanizing details and their inherent vulnerability just aren’t here. As it is, Love and Sex with Robots feels like a date with a machine.

The theatre at the 92nd Street Y was packed. It was a sold out house for three prominent international authors. Umberto Eco read in Italian from his well-known novel Foucault’s Pendulum in Italian, while its English counterpart scrolled across a screen behind him. (This surprised me. I expected him to read from his more recent novel The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana. Foucault’s Pendulum had come out twenty years ago.) I liked the idea of the author reading his work in the language it was originally written (as Rushdie later said, we should hear the words the author actually wrote). But the text scrolled far too fast and the last lines didn’t move for a long time as Eco finished his reading. Next, Rushdie emerged. In a major blunder, ushers paced down the aisle asking for question cards. You see, the Y decided that the best way it would conduct its audience Q&A was by having the audience write down their questions on little cards provided in their programs, then giving these to the ushers, who would then pass these cards up to the moderator. However, it wasn’t right to collect the question cards as one author stopped reading and another author started. We were too busy listening to think about the questions we might want to ask.

The theatre at the 92nd Street Y was packed. It was a sold out house for three prominent international authors. Umberto Eco read in Italian from his well-known novel Foucault’s Pendulum in Italian, while its English counterpart scrolled across a screen behind him. (This surprised me. I expected him to read from his more recent novel The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana. Foucault’s Pendulum had come out twenty years ago.) I liked the idea of the author reading his work in the language it was originally written (as Rushdie later said, we should hear the words the author actually wrote). But the text scrolled far too fast and the last lines didn’t move for a long time as Eco finished his reading. Next, Rushdie emerged. In a major blunder, ushers paced down the aisle asking for question cards. You see, the Y decided that the best way it would conduct its audience Q&A was by having the audience write down their questions on little cards provided in their programs, then giving these to the ushers, who would then pass these cards up to the moderator. However, it wasn’t right to collect the question cards as one author stopped reading and another author started. We were too busy listening to think about the questions we might want to ask.

That said, the vagina has more wiggle room than the penis. Erica Jong called the fairer genitalia an “all-weather” organ, suitable for use anytime as long as a bottle of lubricant is in arm’s reach. The passive nature of the vagina makes it easier for a heterosexual man to suspend disbelief and engage in activities such as prostitution and doll play. Not so with the penis. The Viagra discussion notwithstanding, arousal must produce a man’s erection, which silently proclaims, you are sexy and desirable to me. It is an honest organic response, not the proper execution of computer programming. An erection imparts affirmation that a phallus will never evoke.

That said, the vagina has more wiggle room than the penis. Erica Jong called the fairer genitalia an “all-weather” organ, suitable for use anytime as long as a bottle of lubricant is in arm’s reach. The passive nature of the vagina makes it easier for a heterosexual man to suspend disbelief and engage in activities such as prostitution and doll play. Not so with the penis. The Viagra discussion notwithstanding, arousal must produce a man’s erection, which silently proclaims, you are sexy and desirable to me. It is an honest organic response, not the proper execution of computer programming. An erection imparts affirmation that a phallus will never evoke. Levy is an international chess champion and the author of dozens of books on artificial intelligence and computer gaming. His passion for his subject is evidenced by a long list of international credentials concerning those topics. He led a team to win the 1997 Loebner Prize (world championship for conversational computer software) and is currently the president of the International Computer Games Association. In 1968, Levi wagered that no computer would beat him at chess within the next ten years. He won that bet against his fellow AI aficionados, which garnered him considerable notability. Eleven years later, however, he was defeated by the computer program “Deep Thought,” which leads me to the heart of the trouble with Love and Sex with Robots.

Levy is an international chess champion and the author of dozens of books on artificial intelligence and computer gaming. His passion for his subject is evidenced by a long list of international credentials concerning those topics. He led a team to win the 1997 Loebner Prize (world championship for conversational computer software) and is currently the president of the International Computer Games Association. In 1968, Levi wagered that no computer would beat him at chess within the next ten years. He won that bet against his fellow AI aficionados, which garnered him considerable notability. Eleven years later, however, he was defeated by the computer program “Deep Thought,” which leads me to the heart of the trouble with Love and Sex with Robots.