Charles Yu appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #424. He is most recently the author of How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Saying goodbye before saying hello.

Author: Charles Yu

Subjects Discussed: Accusations of egomania, Abbott and Costello, the real Charles Yu vs. the fictive Charles Yu, writing a novel in a nonlinear fashion, how time travel encourages emotional truth, father-son bonding experiences, viewing your own memory as a bystander, freedom of movement within text, skimming vs. careful reading, intense reading experiences, Finnegans Wake and recursive reading, David Foster Wallace, Faulkner, lack of concentration and the Internet, Dan O’Bannon, Red Dwarf, working stiff protagonists, schlubbiness, inner worlds and inner schlubs, gazes and looks within fiction, non-conflict conflict, drawbacks within time travel novels and extended meditation, diagrams contained within the middle of books, loneliness and sexbots, genre and MacGuffins, sticking with skeletal plot no matter what, gobbledygook and cryogenics, Richard Feynman, legitimate and illegitimate research into quantum mechanical texts, the appeal of language vs. the appeal of ideas, the fun tone of fake science, “Problems for Self-Study” (PDF) as a precursor for How to Live Safely, schematics as the genesis for finished fiction, smudging a list and Silly Putty, not laughing at one’s own comic writing, the funny qualities of email vs. fiction, Twitter, Moisture Man, schlubbiness vs. Asimov’s robotics, Phil the Computer Program, crushing the sentient feelings of computers in the future, reconstructing individual AI personalities from Twitter feeds, personality algorithms generated from books, books as simulacrums of consciousness, fakery injected into fakery, stories that are told in other voices, the use of hypothetical robots within fiction, fakery used to aid the idea of conflict, tangible boxes that have levers and stuff, and projections of machinery.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Yu: I think schlubbiness is my default protagonist, unfortunately.

Correspondent: Oh yeah?

Yu: Yeah. I’ve yet to write — and lots of people have pointed it out, but really now it’s coming into focus. Because I realize how much I kind of schlub it up when I start designing. Not designing. But that’s how they come out. Maybe it’s a reflection of my inner schlub that I don’t know how to create a dashing hero yet.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Yu: I want to.

Correspondent: You’ve made attempts? (laughs)

Yu: I’ve probably made some half-hearted attempts. But I’m going to try harder to make a non-schlub protagonist. Because I want to try something different. I think it’s partly a reflection of just the worlds too that these guys live in — and so far they have been guys. That they’re sort of slightly broken, damaged worlds in the stories I’ve written too, for the most part. So they fit into that, I guess.

Correspondent: Inner worlds create inner schlubs.

Yu: (laughs)

Correspondent: So you’re saying that the schlubbiness is dictated more by the worldbuilding that you’re undergoing in a short story or a novel. Or the fact that you can be more, I suppose, confidently schlubby on paper as opposed to life.

Yu: No, I think the worlds make the schlub. And I think there’s a bit of a change in the Charles Yu character. I think he tries to stop being such a depressed navel gazer and look forward a bit. I mean, I don’t mean to spoil anything for people who haven’t read it and want to read it. But it also seems easier for me to see the change that I want to have in the character. Or to start with somebody who’s really sort of broken. And have them find some measure of some resolution or something.

Correspondent: Well, on that subject of something else being in plain sight — no pun intended for the next question, which is rather elaborate — in describing a sexbot, you write, “Something about the look in her eyes gets me, even though I know they aren’t really eyes.” When an older Charles observes a younger ten-year-old Charles and his father, you write, “And it looks as if they are staring, not through me, but right back at me, and with their minds immersed in the theory of time travel and their eyes fixed on the future.” Late in the book, when Charles Yu faces a serious existential crisis and contemplates several options, he has one choice. “Nor can I change the path of my body, the words from my lips, not even the focus of my eyes.” So it’s interesting to me that Charles Yu — in the book, not you — is just as aware of these fixed looks and staring into these windows of the soul and he can’t quite connect through the space-time continuum and through the act of writing. So I’m curious where this interest in eyes came about. Was this a way of informing the reader on what Charles Yu is missing out on? These recurring stares? This recurring communication with souls and the like?

Yu: Yeah, that was an elaborate question. So I’m going to try and give an appropriately elaborate answer.

Correspondent: Fantastic.

Yu: It only seems right to do justice for that question. Because I think you’ve put your finger on something I was trying to get out. Which is this kind of feeling of missed connection across time. And yet when Father and Mother are gazing toward the future, or Charles is looking at something, can sometimes sense something in the room, it’s this idea that now that future Charles is in that room looking back, maybe the first time around you feel the future there too. And that’s what you’re looking at. But you can’t connect. As you pointed out, you’re not directly looking at it. But there’s a sense in which what’s going to happen is already in the room with you and you can feel it there. You can’t see it yet. And then in the past, you can see it now. But you can’t change anything about it. And that also, in terms of narrative mechanics, there is some squiahiness to my sci-fi here. It’s not hard at all.

Correspondent: Squishy and schlubby. This is great.

Yu: That’s right. Yeah. Not hard sci-fi. Squishy, schlubby, mushy sci-fi.

Correspondent: It was never on the jacket copy though.

Yu: (laughs) But the one constraint I wanted to have in there. And I won’t pretend to know whether or not I ever violated it. But I think I said as a rule that you can’t change the past. And if you do, you shoot off into an alternate reality. But here’s where the sort of paradox comes in. You can’t — like the Charles when he realizes he’s caught in his time loop, if he wants to stay within his chronology, he can’t say or do anything different. And he can’t even look in a different place. But he can think something different. So I’m drawing what I understand is an artificial distinction between thinking and doing. But that was sort of where that comes from. It’s that even if my eyes — you know, everything I do is exactly the same as the first time down to where I’m looking. I have the tiny degree of freedom of changing how I feel about the same experience. Therein sort of lies the difference where he goes through this for the second time, basically.

Correspondent: Any alteration in the time stream causes the protagonist Charles Yu to not be able to see or to interact. Which is a really bummer offshoot of any of his decisions. Even a stray drift from this prevents him from doing anything. That’s quite a high wire act you set for yourself as a writer. How do you generate conflict if you have a protagonist who is incapable of doing what most humans are doing? When his pro-active decisions create this mess?

Yu: Right. That was a problem. It really was. And I’m not sure I surmounted that problem. I think if I were to judge by some of the responses I’ve gotten, some people have said, “Not enough conflict in this book.” And I think that’s a fair statement. And what conflict there is is necessarily pretty internal. One drawback for having a time loop novel and one in which the form of time travel requires you cannot change anything.

Correspondent: Was this form of non-conflict conflict the best way for you to explore these issues of memory and consciousness and choice and loneliness? That that was really the only comfortable or reader-accessible way for you to tackle these issues?

Yu: I think so. It’s the only way I could figure out how. I mean, I wanted it to be sort of an extended meditation on something. And that doesn’t make it sound terribly attractive when you’re thinking of reading and writing a book that’s going to last for a couple hundred pages at least on a meditation. But it was, to me, the only form that — it just kind of grew out of what I was writing about. For better or worse. So I was like, “Well, this is going to be the plot.” And as you know, there’s that diagram in the middle of the book, which sort of gives you the plot points. And there aren’t many of them But that’s what I did pretty early, like very early I drew that. And I said I’m going to stick to this. Because this will keep me from getting lost and violating the rules I’ve set up. And keep me focused on exploring the ideas of consciousness and memory that you pointed out.

The Bat Segundo Show #424: Charles Yu (Download MP3)

That said, the vagina has more wiggle room than the penis. Erica Jong called the fairer genitalia an “all-weather” organ, suitable for use anytime as long as a bottle of lubricant is in arm’s reach. The passive nature of the vagina makes it easier for a heterosexual man to suspend disbelief and engage in activities such as prostitution and doll play. Not so with the penis. The Viagra discussion notwithstanding, arousal must produce a man’s erection, which silently proclaims, you are sexy and desirable to me. It is an honest organic response, not the proper execution of computer programming. An erection imparts affirmation that a phallus will never evoke.

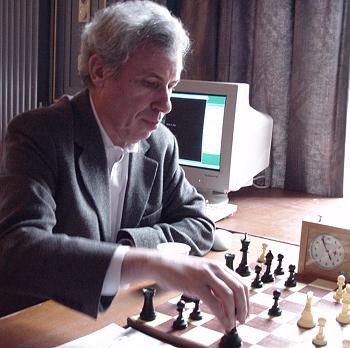

That said, the vagina has more wiggle room than the penis. Erica Jong called the fairer genitalia an “all-weather” organ, suitable for use anytime as long as a bottle of lubricant is in arm’s reach. The passive nature of the vagina makes it easier for a heterosexual man to suspend disbelief and engage in activities such as prostitution and doll play. Not so with the penis. The Viagra discussion notwithstanding, arousal must produce a man’s erection, which silently proclaims, you are sexy and desirable to me. It is an honest organic response, not the proper execution of computer programming. An erection imparts affirmation that a phallus will never evoke. Levy is an international chess champion and the author of dozens of books on artificial intelligence and computer gaming. His passion for his subject is evidenced by a long list of international credentials concerning those topics. He led a team to win the 1997 Loebner Prize (world championship for conversational computer software) and is currently the president of the International Computer Games Association. In 1968, Levi wagered that no computer would beat him at chess within the next ten years. He won that bet against his fellow AI aficionados, which garnered him considerable notability. Eleven years later, however, he was defeated by the computer program “Deep Thought,” which leads me to the heart of the trouble with Love and Sex with Robots.

Levy is an international chess champion and the author of dozens of books on artificial intelligence and computer gaming. His passion for his subject is evidenced by a long list of international credentials concerning those topics. He led a team to win the 1997 Loebner Prize (world championship for conversational computer software) and is currently the president of the International Computer Games Association. In 1968, Levi wagered that no computer would beat him at chess within the next ten years. He won that bet against his fellow AI aficionados, which garnered him considerable notability. Eleven years later, however, he was defeated by the computer program “Deep Thought,” which leads me to the heart of the trouble with Love and Sex with Robots.