Most my reading this year was devoted to research for several projects and to dead authors — in particular, just about everything ever written by Henry Green, a good chunk of Penelope Fitzgerald, and many volumes of the great Iris Murdoch, whose volume of letters (forthcoming in January here in the States) I will undoubtedly opine on somewhere. The nice thing about the dead is that you never have to worry about their social media presence, much less being that hip kid on Twitter being the first to skim through a status galley that nobody will give a toss about in six months. But I did squeeze in some time for contemporary titles and what follows is a list of exceedingly worthwhile books that greatly moved me and are very much worth your time:

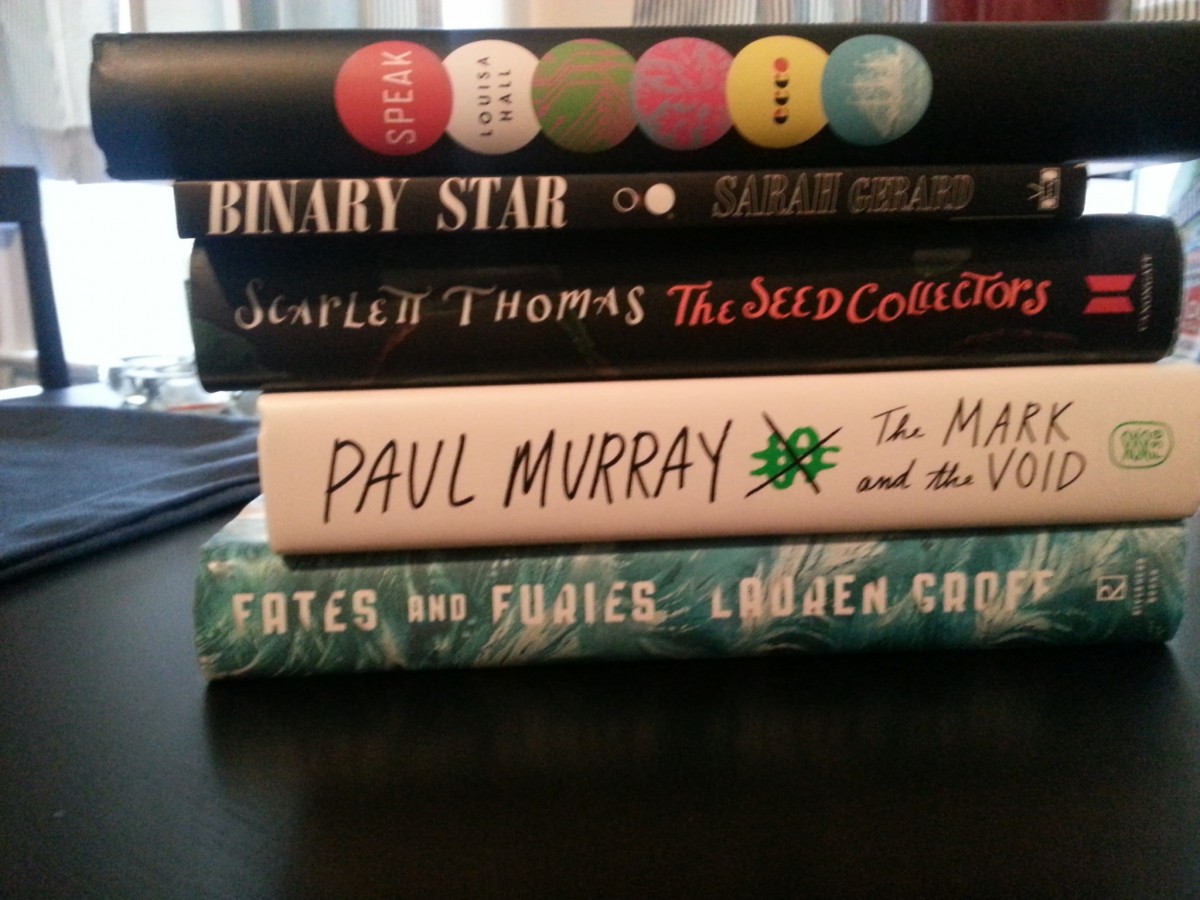

Sarah Gerard, Binary Star: Among many deceptively slim volumes published this year containing great wisdom about consciousness and interconnectedness, Gerard’s road trip saga was a standout. The couple at the center of this often fierce, sometimes breezy, sometimes heartbreaking novel is a woman who suffers from aneroxia and a man who is an alcoholic. The juxtaposition of rocket imagery and the nameless anorexic woman’s physical erosion from rapid weight loss finds a painful cadence with clipped sentences and a dialectic involving vegan anarchism. One reads this book, wondering if we are living in a world of disorders, or whether judgment itself may be causing us to see disorders. The book’s epigraph to Raoul Vaneigem’s The Revolution of Everyday Life hints further at the nature of this perceptual manipulation and one is left wondering what “irreducible core of creativity” that the main character may find. Perhaps it’s not meant to be glimpsed. This woman is, after all, becoming quite blind herself. Perhaps all we have left, wherever we are, is in the stars.

Sarah Gerard, Binary Star: Among many deceptively slim volumes published this year containing great wisdom about consciousness and interconnectedness, Gerard’s road trip saga was a standout. The couple at the center of this often fierce, sometimes breezy, sometimes heartbreaking novel is a woman who suffers from aneroxia and a man who is an alcoholic. The juxtaposition of rocket imagery and the nameless anorexic woman’s physical erosion from rapid weight loss finds a painful cadence with clipped sentences and a dialectic involving vegan anarchism. One reads this book, wondering if we are living in a world of disorders, or whether judgment itself may be causing us to see disorders. The book’s epigraph to Raoul Vaneigem’s The Revolution of Everyday Life hints further at the nature of this perceptual manipulation and one is left wondering what “irreducible core of creativity” that the main character may find. Perhaps it’s not meant to be glimpsed. This woman is, after all, becoming quite blind herself. Perhaps all we have left, wherever we are, is in the stars.

Lauren Groff, Fate and Furies: I was late to the party, but I’m so glad I took the plunge. This is an extremely well-observed portrait of a marriage built on a mirage. Groff expertly disguises the rapid-fire courtship of Lotto and Mathilde with a fusillade of college friends who live and disappear and reemerge as the couple enters middle age. That Groff has made the troubled husband a middling playwright and submerged this harrowing man in famous Greek classics (including a riff on Antigone) attests to the time-honored theater that humans have been encasing their relationships in for time immemorial. Almost serving as counterpoint to Mark Z. Danielewski’s respectable two volumes of The Familiar, Groff has also included a mysterious commentator within the narrative who offers bracketed asides. As painful as this novel can be to read for anyone who has been through a very long and sour relationship predicated on lies (or who has to watch a friend going through something like this), the sorrow nevertheless beckons the reader to summon more honesty, openness, and communication in real life. And for that reminder alone, Groff has emerged as a writer whose every future volume I will read upon publication.

Lauren Groff, Fate and Furies: I was late to the party, but I’m so glad I took the plunge. This is an extremely well-observed portrait of a marriage built on a mirage. Groff expertly disguises the rapid-fire courtship of Lotto and Mathilde with a fusillade of college friends who live and disappear and reemerge as the couple enters middle age. That Groff has made the troubled husband a middling playwright and submerged this harrowing man in famous Greek classics (including a riff on Antigone) attests to the time-honored theater that humans have been encasing their relationships in for time immemorial. Almost serving as counterpoint to Mark Z. Danielewski’s respectable two volumes of The Familiar, Groff has also included a mysterious commentator within the narrative who offers bracketed asides. As painful as this novel can be to read for anyone who has been through a very long and sour relationship predicated on lies (or who has to watch a friend going through something like this), the sorrow nevertheless beckons the reader to summon more honesty, openness, and communication in real life. And for that reminder alone, Groff has emerged as a writer whose every future volume I will read upon publication.

Louisa Hall, Speak: Could human beings become addicted to robots? Why not? We walk the streets staring down at our phones, saturating our Instagram accounts with relentless photos, and logging every sordid detail about our lives on social media. Suppose that level of addiction had a conscience attached to it. And suppose it was modeled on the diary of a 17th century woman. Suppose further that an ELIZA-like program was somehow an AI missing link between the diary and the robots and that Alan Turing, just on the throes of being subjected to DES and its accompanying gynecomastia by a frightened homophobic government, was involved. You begin to have some inkling of what Hall’s ever thoughtful novel, which is brave enough to explore how our seduction to technology and its many byproducts may just be dwarfing the more important seduction of real life.

Louisa Hall, Speak: Could human beings become addicted to robots? Why not? We walk the streets staring down at our phones, saturating our Instagram accounts with relentless photos, and logging every sordid detail about our lives on social media. Suppose that level of addiction had a conscience attached to it. And suppose it was modeled on the diary of a 17th century woman. Suppose further that an ELIZA-like program was somehow an AI missing link between the diary and the robots and that Alan Turing, just on the throes of being subjected to DES and its accompanying gynecomastia by a frightened homophobic government, was involved. You begin to have some inkling of what Hall’s ever thoughtful novel, which is brave enough to explore how our seduction to technology and its many byproducts may just be dwarfing the more important seduction of real life.

Paul Murray, The Mark and the Void: Some critics have accused Murray of tackling too much in this hilarious, insightful, and often poignant book — almost as if the comic novel is not permitted ambition in our increasingly intolerant age. But Murray’s talent has sharpened considerably since Skippy Dies and we are all the richer for it. This penetrating tale involves a writer named Paul who asks a banker named Claude if he can follow him for a novel Paul’s writing about the Everyman. Paul, of course, has another ill-fated plan up his sleeve, one I don’t have it in my heart to give away. I’ll just say that Murray’s many twists and turns lend this book a kind of madcap momentum that, even before we’re aware of it, leads us into very heartfelt questions about what it is to be human at a moment in history in which banks resort to the most sinister plans imaginable (including building a golf course on an island fated to be flooded from climate change, under the theory that the investors can win back their investment from an insurance payout). What makes Murray such a great writer is the way he keeps his cleverness close to his chest. He is more interested in winning over readers, whoever they may be, by appealing to many brows, whether it be a Rothko-like painting that hangs in a rich man’s study or a sloppy low comedy Russian accomplice named Igor. This novel is a gripping portrait on what may be happening to our world as we surrender our invention and curiosity. At one point, an interoffice memo reading “All that glitters is not gold” is distributed throughout the bank. Not a single employee remembers this as a Shakespeare quote — indeed, a quote from one of the Bard’s most infamous plays about usury — but all take this “mantra” quite literally as a strategy to act on. Yet for all this, Murray never ridicules his subjects, which aligns this book with John P. Marquand’s underrated novel, Point of No Return (also about a banker). This novel is so terrific that I’m willing to suggest that Paul Murray may be our best shot at an Evelyn Waugh (albeit a kinder one) for the 21st century.

Paul Murray, The Mark and the Void: Some critics have accused Murray of tackling too much in this hilarious, insightful, and often poignant book — almost as if the comic novel is not permitted ambition in our increasingly intolerant age. But Murray’s talent has sharpened considerably since Skippy Dies and we are all the richer for it. This penetrating tale involves a writer named Paul who asks a banker named Claude if he can follow him for a novel Paul’s writing about the Everyman. Paul, of course, has another ill-fated plan up his sleeve, one I don’t have it in my heart to give away. I’ll just say that Murray’s many twists and turns lend this book a kind of madcap momentum that, even before we’re aware of it, leads us into very heartfelt questions about what it is to be human at a moment in history in which banks resort to the most sinister plans imaginable (including building a golf course on an island fated to be flooded from climate change, under the theory that the investors can win back their investment from an insurance payout). What makes Murray such a great writer is the way he keeps his cleverness close to his chest. He is more interested in winning over readers, whoever they may be, by appealing to many brows, whether it be a Rothko-like painting that hangs in a rich man’s study or a sloppy low comedy Russian accomplice named Igor. This novel is a gripping portrait on what may be happening to our world as we surrender our invention and curiosity. At one point, an interoffice memo reading “All that glitters is not gold” is distributed throughout the bank. Not a single employee remembers this as a Shakespeare quote — indeed, a quote from one of the Bard’s most infamous plays about usury — but all take this “mantra” quite literally as a strategy to act on. Yet for all this, Murray never ridicules his subjects, which aligns this book with John P. Marquand’s underrated novel, Point of No Return (also about a banker). This novel is so terrific that I’m willing to suggest that Paul Murray may be our best shot at an Evelyn Waugh (albeit a kinder one) for the 21st century.

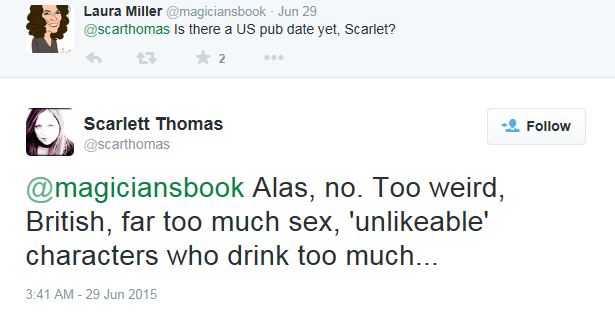

Scarlett Thomas, The Seed Collectors: As I wrote about this novel’s considerable achievements in September:

Scarlett Thomas, The Seed Collectors: As I wrote about this novel’s considerable achievements in September:

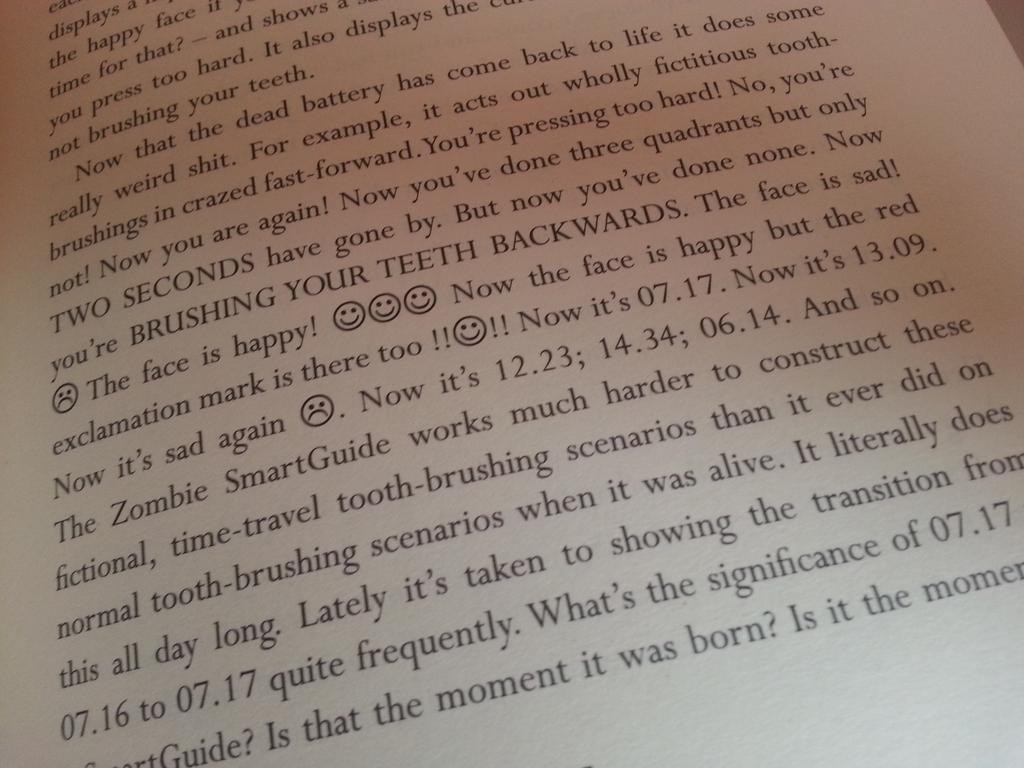

The Seed Collectors is holding up a very large mirror to the Quantified Self movement, whereby everything we do in this world creates data, collected and hawked and redistributed in ways that are not necessarily compatible with our complex feelings. The above passage, a glorious pisstake on gamification, sees Ollie, a man who Bryony is considering sleeping with, at the mercy of an Oral B Triumph SmartGuide, an alarmingly horrific (and quite real) device that demands its practitioners to brush teeth in highly specific ways, with emoticons rewarding a commonplace activity with Candy Crush-style perdition. Even a monstrous man named Charlie, who is introduced sexually violating a blind date before the thirty page mark (perhaps another reason why American houses lack the spine to publish this book), is someone who clings to a list of attributes that he’d like to see in “my perfect girlfriend.” And if quantification is the deadly condition uniting all these characters, then how do these disparate characters live? As the novel progresses, Thomas introduces a great deal of dialogue in which the speakers are never identified. And this missing data, so to speak, steers the reader towards an emotional intuition well outside any data subset. And as Thomas serves up more twists and revelations, we come to understand that it is still possible in our age of unmitigated surveillance to be attuned to our private thoughts (though for how long?). The novel, which we have believed all along to be thoroughly structured, has perhaps been a lifelike unstructured mess all along. And this unanticipated alignment between fiction and our data-plagued world feels more artful and poignant than such conceptual stunts as writing a short story composed entirely of tweets. It makes The Seed Collectors almost a cousin to Louisa Hall’s recent novel, the quite wonderful Speak, which used a computer algorithm to determine which of its five perspectives would be on deck next. But even if you don’t want to play this game of six-dimensional chess, The Seed Collectors still works as a sprightly narrative on its own terms, at times reading like an Iris Murdoch novel written for our time and beyond.

Hanya Yanagahira, A Little Life: Nasty little men like Daniel Mendelsohn, a vicious narcissistic troll with a small penis (or so a source informed me; take it for what it is; this is a blind item I have no wish to corroborate), have no real understanding of trauma or pain or abuse, much less the painstaking empathy that friends and family must expend in helping the victim out of a self-perpetuating abyss. Thus, this critic is ill-equipped (in more ways that one) to speak of the relentless cycle of violence and vitriol that victims of abuse must not only live with, but often eke out to the people who love them. A Little Life is not a “woman’s novel.” It is a first-rate novel, independent of that belittling sobriquet, that dares to explore the uncomfortable interior of the ineffable in ways that misogynist novels like Jonathan Franzen’s Purity lack the honesty or the heart to broach. Its central character, Jude, is brilliant in all the right ways and scarred in all the wrong ones. While the prose does lean on a dismaying magazine shorthand, Yanagahira’s truths hit hard enough to overturn this stylistic cavil. “We didn’t know how to help him because we lacked the imagination needed to diagnose the problems,” a sentiment uttered by one of Jude’s friends, may sound trite to a heartless snob like Mendelsohn, but it is an especially succinct expression of America’s relationship to the afflicted. The book covers many years, often far into the future, and smartly avoids mentioning any current events. And that is because the problem of abuse needs to be isolated and examined at length, especially as we see its terrible culmination in the many mass shootings that have riddled our nation this year. As a victim of abuse, I cried tears of recognition when Jude allowed a man to assault and abuse him. For there was a time in my twenties when I allowed a lover into my life who did something quite similar. It took me years to recognize the threads that led back to an earlier life in which my very parents physically and emotionally abused me. And while I am now doing very well and am now the happiest I have been in years, I am ever on the alert for any small misstep that could send me even a few feet away from the self-destructive pit. Because as tough and as resilient and as seemingly well-adjusted as we survivors are, there’s always a chance. So Yanagahira’s novel almost served as exposure therapy, especially since I was down and out when I read it. For anyone fortunate enough to never experience abuse, I urge you to read A Little Life. Its worldview is far from “little,” unless you’re a small-minded hyperbolic attention whore paid to bray sociopathic sentences on command in one of the literary world’s declining institutions.

Hanya Yanagahira, A Little Life: Nasty little men like Daniel Mendelsohn, a vicious narcissistic troll with a small penis (or so a source informed me; take it for what it is; this is a blind item I have no wish to corroborate), have no real understanding of trauma or pain or abuse, much less the painstaking empathy that friends and family must expend in helping the victim out of a self-perpetuating abyss. Thus, this critic is ill-equipped (in more ways that one) to speak of the relentless cycle of violence and vitriol that victims of abuse must not only live with, but often eke out to the people who love them. A Little Life is not a “woman’s novel.” It is a first-rate novel, independent of that belittling sobriquet, that dares to explore the uncomfortable interior of the ineffable in ways that misogynist novels like Jonathan Franzen’s Purity lack the honesty or the heart to broach. Its central character, Jude, is brilliant in all the right ways and scarred in all the wrong ones. While the prose does lean on a dismaying magazine shorthand, Yanagahira’s truths hit hard enough to overturn this stylistic cavil. “We didn’t know how to help him because we lacked the imagination needed to diagnose the problems,” a sentiment uttered by one of Jude’s friends, may sound trite to a heartless snob like Mendelsohn, but it is an especially succinct expression of America’s relationship to the afflicted. The book covers many years, often far into the future, and smartly avoids mentioning any current events. And that is because the problem of abuse needs to be isolated and examined at length, especially as we see its terrible culmination in the many mass shootings that have riddled our nation this year. As a victim of abuse, I cried tears of recognition when Jude allowed a man to assault and abuse him. For there was a time in my twenties when I allowed a lover into my life who did something quite similar. It took me years to recognize the threads that led back to an earlier life in which my very parents physically and emotionally abused me. And while I am now doing very well and am now the happiest I have been in years, I am ever on the alert for any small misstep that could send me even a few feet away from the self-destructive pit. Because as tough and as resilient and as seemingly well-adjusted as we survivors are, there’s always a chance. So Yanagahira’s novel almost served as exposure therapy, especially since I was down and out when I read it. For anyone fortunate enough to never experience abuse, I urge you to read A Little Life. Its worldview is far from “little,” unless you’re a small-minded hyperbolic attention whore paid to bray sociopathic sentences on command in one of the literary world’s declining institutions.

But if my plaudits aren’t enough to sell you on A Little Life, I should also point out that the only reason A Little Life is not pictured among the books in the header image is because, months ago, someone who had spent the night at my apartment and heard me rave about it happened to pilfer it.