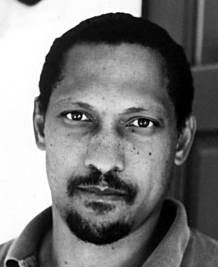

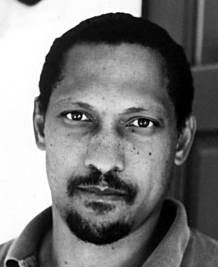

Percival Everett appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #295.

Percival Everett is most recently the author of I Am Not Sidney Poitier.

[For related links, check out Percival Everett Week over at Emerging Writers Network, as well as my specific thoughts about Everett’s most recent novel.]

Condition of Mr. Segundo: He is not Percival Everett.

Subjects Discussed: Name-related jokes, puns and internal metaphors, the many ways to pronounce “Le-a,” literal misunderstandings, whether there really is a Ted Turner, Bill Cosby’s Pound Cake speech, Richard Power’s Generosity, the relationship between reality and fiction, truth vs. reality, the “magic” of writing, stress, on not paying attention to the publishing industry, making the next book, not caring about the reader, on not writing commercial successes, the impulse to entertain, Everett’s world of Dionysus, reader reactions and interpretations, having no affection for previous books, becoming a better writer, the “experimental” nature of Wounded, outlandish one-dimensional figures and subdued prose, I Am Not Sidney Poitier as a “novel of ideas,” on not knowing how to write a novel, artistic creation and gleeful sabotage, narrative worlds and anarchy, Everett’s novels as concrete recreations, loving children geniuses and idiots alike, worldbuilding, subverting subjective character understanding, limitations, writing novels as a playground, having an interest in religion while remaining an “apath,” psychics for horses, believing with character belief, laundry list descriptions, strategic use of language, the relationship between story and language.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I recently read Richard Powers’s forthcoming novel, Generosity, which deals with the notion of what a novel really is and what ideas and characters really are. And I’m very curious to put this question to you. To what degree do you need reality to start from? And to what degree do you feel the need to be faithful to reality? Or even faithful to real-life figures? Or can you accept a Percival Everett figure in this who also happens to have a book called Erasure?

Correspondent: I recently read Richard Powers’s forthcoming novel, Generosity, which deals with the notion of what a novel really is and what ideas and characters really are. And I’m very curious to put this question to you. To what degree do you need reality to start from? And to what degree do you feel the need to be faithful to reality? Or even faithful to real-life figures? Or can you accept a Percival Everett figure in this who also happens to have a book called Erasure?

Everett: First, I owe nothing to reality. But, of course, for any novel to work, in spite of my disregard — maybe even my disdain for facts — truth is important. If it’s not true, you can’t stay with it. You won’t believe it. And there is no work. But truth has nothing to do with reality or facts.

Correspondent: But you do have names to draw from. Not just in this book, but also in your previous books. Thomas Jefferson, Strom Thurmond. You’re a guy who likes real names like this. And so, as such, I have to ask. Is it just a constant influx of information from newspapers that is your creative muse? Where do you stop from reality and start with the inventive process? Or the misunderstandings we’re talking about?

Everett: Well, it depends on the work. But I read all the time. So it just depends on what comes to me. Some figures just present themselves as too alluring to ignore. How could I go through my life and not at some point address Strom Thurmond? (laughs)

Correspondent: Yeah. Sure. But it can’t just be a simple impulse. Because obviously…

Everett: Why not?

Correspondent: Because I’m thinking when you set out to write a novel — and I’m not you obviously — but when you set out to find a concept or put your finger on something, is it a matter of instinctively knowing that that’s something to riff on or something to expand further? Or do you have any plan like this?

Everett: Sometimes I don’t have a plan. Sometimes it’s hit or miss. Trial or error. Feast or famine. All of those duals. I don’t know. For me, the way novels come together is magic. And I only question it so much.

Correspondent: Magic. Magic through pure work? You’re a prolific guy.

Everett: Yeah, I suppose. Yeah. It won’t get done unless I do it. So I try to do it. And I don’t stress.

Correspondent: You don’t stress? Never stressed at all?

Everett: I try not to be. There’s no reason to get upset about anything. Especially work. And then it happens. And the more it happens, the less stressed I become.

BSS #295: Percival Everett (Download MP3)

This text will be replaced

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Correspondent: I recently read Richard Powers’s forthcoming novel, Generosity, which deals with the notion of what a novel really is and what ideas and characters really are. And I’m very curious to put this question to you. To what degree do you need reality to start from? And to what degree do you feel the need to be faithful to reality? Or even faithful to real-life figures? Or can you accept a Percival Everett figure in this who also happens to have a book called Erasure?

Correspondent: I recently read Richard Powers’s forthcoming novel, Generosity, which deals with the notion of what a novel really is and what ideas and characters really are. And I’m very curious to put this question to you. To what degree do you need reality to start from? And to what degree do you feel the need to be faithful to reality? Or even faithful to real-life figures? Or can you accept a Percival Everett figure in this who also happens to have a book called Erasure?