Four new podcasts were released today at The Bat Segundo Show. And since we’re on the subject of Segundo, what follows is a short excerpt from my conversation with Philadelphia-based artist Charles Burns, who I chatted with during a recent visit through New York.

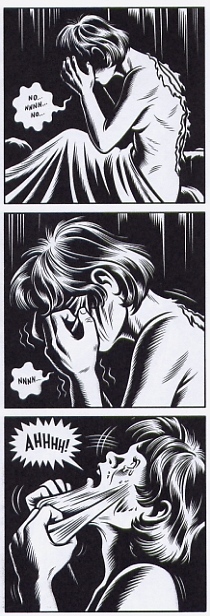

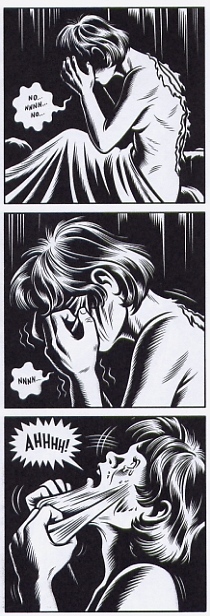

You might know Burns’s work from his advertisements or his illustrations for The Believer. But he’s best known as the writer and illustrator of the graphic novel, Black Hole, a compilation of his twelve-volume comic book. Burns worked on this over the course of ten years. And one of its remarkable qualities is the way that it remains remarkably consistent in its tone, despite the fact that Burns saw his two daughters grow up as he patiently put his work together. Black Hole depicts the story of a sexually transmitted disease that afflicts various teenagers in the Pacific Northwest. The work is very much a Rorschach test for the reader. One might infer a parable about AIDS or, if you wanted to get really reductive, innocence lost. Or it can be simply enjoyed as a dark tale of American adolescence gone awry.

You might know Burns’s work from his advertisements or his illustrations for The Believer. But he’s best known as the writer and illustrator of the graphic novel, Black Hole, a compilation of his twelve-volume comic book. Burns worked on this over the course of ten years. And one of its remarkable qualities is the way that it remains remarkably consistent in its tone, despite the fact that Burns saw his two daughters grow up as he patiently put his work together. Black Hole depicts the story of a sexually transmitted disease that afflicts various teenagers in the Pacific Northwest. The work is very much a Rorschach test for the reader. One might infer a parable about AIDS or, if you wanted to get really reductive, innocence lost. Or it can be simply enjoyed as a dark tale of American adolescence gone awry.

Since Burns has conducted many interviews for his magnum opus, the challenge was to come up with a few conversational angles that he hadn’t encountered. But the interview frequently drifted into abstract personal memories when I asked him about a specific facet of Black Hole, demonstrating perhaps that artistic ambiguities aren’t always so easily pinpointed.

Correspondent: You’ve probably seen Vanessa Raney’s really lengthy critical essay of Black Hole, where she analyzes your panels quite in-depth. And I actually wanted to ask you about a comparison she made. She pointed out that Keith, Chris, and Eliza actually represent the same relationship structure in Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit. And I wanted to ask you about this. Was Sartre ever on the mind in concocting this narrative? How did the relationship structure begin?

Burns: Boy, that’s a good question. I don’t know that I’ve read the essay that you’re referring to. But there have been some questions asked along those lines before. It really wasn’t an influence or that wasn’t in my mind when I was creating the story. I guess I was trying to create these characters. Two very different types of women. The main character is just coming to terms with the differences between them and his attraction to them. His initial attraction to Chris, a girl that he admires from his biology class, is this very kind of clean-cut — what he thinks is kind of clean-cut. The kind of woman that he’s putting on a pedestal. She’s perfect. But he doesn’t really know anything about her at all in reality, other than just that she seems amazing.

And then he meets a very different kind of woman, who’s very much earthy. Much more sexual. And he finds himself attracted to her, much to his dismay. So the story’s really his coming to terms with his reaction, I guess, to these different women.

Correspondent: But no Jean-Paul Sartre.

Burns: No.

Correspondent: Any literary…

Burns: I would love to be able to say that there’s a good comparison there. But, no, that wasn’t the case.

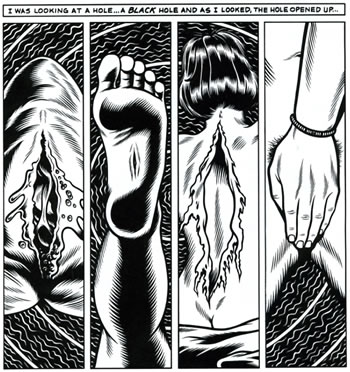

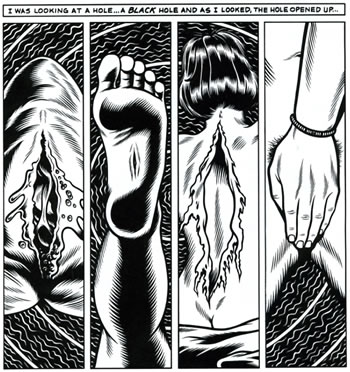

Correspondent: Okay. I also wanted to ask you about some of the anatomical close-ups throughout Black Hole. They remind me very much — in addition to the pustules and the various biological impediments that many of the characters have — it reminds me very much of the sort of World War II venereal disease films.

Correspondent: Okay. I also wanted to ask you about some of the anatomical close-ups throughout Black Hole. They remind me very much — in addition to the pustules and the various biological impediments that many of the characters have — it reminds me very much of the sort of World War II venereal disease films.

Burns: (laughs)

Correspondent: I was wondering. What kind of visual references did you use for these particular decisions? Or was it just more of an intuitive choice?

Burns: It was probably more of an intuitive choice. I mean, there’s those things that I grew up that are out there. I think there’s references in the movie to sitting in the biology health class and looking at — learning about sexuality that way. There’s was always this kind of very strange antiseptic situation. I remember one time in biology class, there was — I guess, what do you call it? — a TA. A student teacher. And there was some film on — I don’t know, reproduction. And she showed the first half of it. And then she abruptly turned the film off. And, of course, everybody in the class said, “Oh, keep running it! We want to see it again! We want to see the rest of it.” And she would say, “No, no, no, no.” And finally she turned it back on. And there was this very graphic portion of the movie, where we were seeing an IUD inserted into a vaginal — (laughs)

Correspondent: Yeah.

Burns: And everybody just immediately got very, very quiet and very, very uncomfortable. Because here’s this — suddenly after seeing these very typical movies about “Your Growing Body,” suddenly we were seeing these very graphic representations. It was an odd moment.

Correspondent: Is it something about that period between, say, 1945 and 1975? Was that very much on the mind — in terms of getting this particular look? Or this particular emphasis on close-ups and warts and the like?

Burns: I don’t know. I guess that’s more of a personal thing. I guess that’s just how my brain works or thinks. Those were the kinds of images that were coming up. Again, it has to do with all the things that you’re subjected to and that you come across from that time period. But nothing as thought out as that, no.

Correspondent: So really it’s more of a personal intuitive experience that you’re drawing upon here? I know…

Burns: That would be a better description.

Correspondent: Yeah, because this leads me into another question. I know that the yearbook photos, or rather the photos on the inside cover, were taken from your own yearbooks.

Burns: Yeah.

Correspondent: And this leads me to ask you about how much of what is in Black Hole is taken from your personal experience, and where do you imagine certain details. I mean, certainly, the disease which plagues all these various people is imagined in some sense. But I’m wondering, in terms of the more personal observations, were these taken more from anecdotes? Were these imagined? On what level did you feel the need to draw upon real life and your own instinct for reimagining behavioral scenarios?

Burns: I mean, my situation growing up was a much more benign situation than what I’m depicting. I mean, there were internal struggles that I was going through, that I think everybody goes through during adolescence, that seemed extremely dramatic and extremely heartrending, difficult times. And I guess I was trying to depict that. What those feelings were. The kind of internal struggle that I was going through.

There are certainly situations in the story that are drawn directly from my life. I never met a half-naked girl with a tail.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Burns: I would have loved to.

Correspondent: Wouldn’t we all really?

Correspondent: Wouldn’t we all really?

Burns: That never happened. My existence was much more sedate and pedestrian, I suppose. But again, these sorts of things were brewing in my mind. My sense of not fitting in. My sense of this kind of internal horror that I was feeling in a lot of situations. Whether they were anywhere near…

Correspondent: Well, in terms of personal experience vs. what you observed, I mean, it seems to me that personal experience is more the motivating impetus for what you put into Black Hole more than anything else. If what I’m understanding you to say is correct. Were you more of an observer or were you one of those types of people?

Burns: I was one of those types of people in varying degrees. Someone was asking me the other day, “Were you a punk?” I was there in all those concerts participating, but I never shaved my head or carved a swastika on my forehead. But yeah, I was there. I guess that’s what I wanted to do too — in the book, talk or just have a realistic look at the times I was growing in. There’s moments in there, even though they’re very sedate, that are very horrific to me. To be sitting in a room for four hours listening to Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon get played over and over, and sitting around with a bunch of guys for hours and hours, is horrific to me.

[The full interview will appear in a future installment of The Bat Segundo Show.]

You might know Burns’s work from his advertisements or his illustrations for The Believer. But he’s best known as the writer and illustrator of the graphic novel, Black Hole, a compilation of his twelve-volume comic book. Burns worked on this over the course of ten years. And one of its remarkable qualities is the way that it remains remarkably consistent in its tone, despite the fact that Burns saw his two daughters grow up as he patiently put his work together. Black Hole depicts the story of a sexually transmitted disease that afflicts various teenagers in the Pacific Northwest. The work is very much a Rorschach test for the reader. One might infer a parable about AIDS or, if you wanted to get really reductive, innocence lost. Or it can be simply enjoyed as a dark tale of American adolescence gone awry.

You might know Burns’s work from his advertisements or his illustrations for The Believer. But he’s best known as the writer and illustrator of the graphic novel, Black Hole, a compilation of his twelve-volume comic book. Burns worked on this over the course of ten years. And one of its remarkable qualities is the way that it remains remarkably consistent in its tone, despite the fact that Burns saw his two daughters grow up as he patiently put his work together. Black Hole depicts the story of a sexually transmitted disease that afflicts various teenagers in the Pacific Northwest. The work is very much a Rorschach test for the reader. One might infer a parable about AIDS or, if you wanted to get really reductive, innocence lost. Or it can be simply enjoyed as a dark tale of American adolescence gone awry. Correspondent: Okay. I also wanted to ask you about some of the anatomical close-ups throughout Black Hole. They remind me very much — in addition to the pustules and the various biological impediments that many of the characters have — it reminds me very much of the sort of World War II venereal disease films.

Correspondent: Okay. I also wanted to ask you about some of the anatomical close-ups throughout Black Hole. They remind me very much — in addition to the pustules and the various biological impediments that many of the characters have — it reminds me very much of the sort of World War II venereal disease films.

The reports promised snow but prevaricated. My mind marinated. You get that feeling when you are conned into picking away at a slice of red velvet cake because it’s there and you have only poor penmanship instead of an able fork. Never mind culinary sullies. The owl’s snooty hoots belied a ballistic solipsism suggesting the sword was mightier than any midnight rambler. And we were rendered into spittle and drivel hoping that flurry would scurry and leave us with some natural marching power.

The reports promised snow but prevaricated. My mind marinated. You get that feeling when you are conned into picking away at a slice of red velvet cake because it’s there and you have only poor penmanship instead of an able fork. Never mind culinary sullies. The owl’s snooty hoots belied a ballistic solipsism suggesting the sword was mightier than any midnight rambler. And we were rendered into spittle and drivel hoping that flurry would scurry and leave us with some natural marching power. The first time I saw a quadruple jump performed live, I was barely a mile from the house I grew up in. It was December 1995.

The first time I saw a quadruple jump performed live, I was barely a mile from the house I grew up in. It was December 1995.  Any doubts about Stojko’s fitness and quad mastery dissipated in practice. Where before I required a working television to count the setup’s 1-2-3, with the edge change and toe pick deep into the ice just before Stojko pulled his body together for four tightly wound revolutions, leaving me a half second to wonder if he would, in fact, land the jump cleanly on one foot, now I could do so in person. He whipped out quad after quad, sometimes in combination, during the practice sessions. The fans, far fewer than the numbers attending Nationals and later the World Championships in Edmonton, responded with the fervor and noise of a crowd twice its size. Stojko was relaxed, jocular, keeping up a perpetual professional equally adept with wide-eyed kids, sycophantic adults, and me — a teenager trying hard to be too cool for school and failing.

Any doubts about Stojko’s fitness and quad mastery dissipated in practice. Where before I required a working television to count the setup’s 1-2-3, with the edge change and toe pick deep into the ice just before Stojko pulled his body together for four tightly wound revolutions, leaving me a half second to wonder if he would, in fact, land the jump cleanly on one foot, now I could do so in person. He whipped out quad after quad, sometimes in combination, during the practice sessions. The fans, far fewer than the numbers attending Nationals and later the World Championships in Edmonton, responded with the fervor and noise of a crowd twice its size. Stojko was relaxed, jocular, keeping up a perpetual professional equally adept with wide-eyed kids, sycophantic adults, and me — a teenager trying hard to be too cool for school and failing.