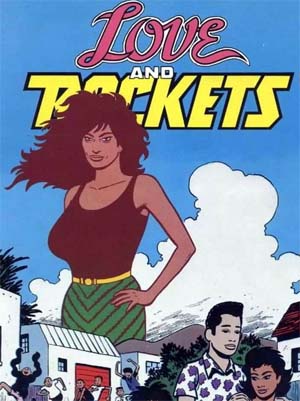

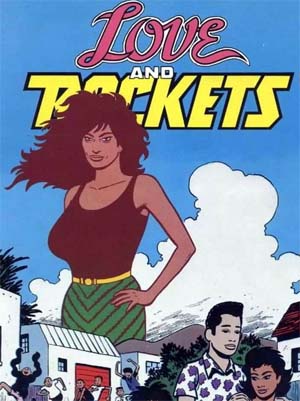

Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez are the creators, writers, and artists for Love and Rockets, the long-running and much acclaimed series celebrating its 30th anniversary this year.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Revisiting a moment in 1969 which sealed his fate.

Authors: Gilbert Hernandez and Jaime Hernandez

Subjects Discussed: Mario Hernandez, the way that Gilbert and Jaime collaborate, the six characters speaking in the same panel with six balloons, egging each other on, growing up in a household in which Gilbert passed down comics to Jaime, The Twilight Zone, Les Miserables, Gilbert’s lack of interest in prose, magical realism, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, creating an entire character based off a certain detail, finding new angles on heavily defined characters, why Maggie’s hairstyles and weight constantly change, how the Love and Rockets run is organized, allowing space in case one of the brothers decides to go long, seeking extreme character qualities, furry culture, turning exploitation on its own head, goofing around, dealing with serious topics (in stories such as “Browntown” and “Farewell, My Palomar”), the problems in elevating superheroes, emotional areas, why Jaime returned to superheroes after a long absence, Gilbert’s frustrations with The Dark Knight Rises, balancing work on L&R in the early days while having jobs, how economic forces have affected Love and Rockets, knowing that L&R wasn’t going to be a hit comic, maintaining a realistic view to make a living, Gilbert’s tendency to work on three comics at the same time, why the Hernandez brothers find women more interesting than men, fondness for butts and curves, the responsibility to imbue all comic book characters with humanity, Jaime being terrified of women in high school, creating a universe run by women, creating stories that are mostly visual (such as “Whoa Nellie” and “Hypnotwist”), the influence of words, L&R as a comic shop with endless back issues, Jack Kirby, why superheroes still have the upper hand in comics, wrestling, following through on a story, the joys of action poses, the influence of Peanuts in the children’s stories, drawing kids with big heads, visually representing a child’s imagination, the difficulty of sizing up the anatomy of a kid standing next up to a grownup, anatomical weak spots, when visual memory works better for art than research, being lazy when drawing hands, scaling children, optical theory, forced perspectives in cinema, eyeballing perspective, vanishing point and backgrounds, Warren Beatty’s Dick Tracy, “An American in Palomar,” whether culture is exploited in telling a story, what the Hernandez brothers hear from academics and fans, when people co-opt L&R as the “pro-Latino comic,” Daniel Clowes, coming up with stories just by looking at a picture, the virtues of not reading all the comics in your collection, reader misinterpretations, valuing the reader’s takeaway, the inspiration that comes from willful blindness, shifting from panel to panel on autopilot, looking back at old material, positive mistakes, and keeping characters alive and material fresh after thirty years.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: Let’s talk about extreme qualities in character. I think of Jaime’s Doyle Blackburn. I mean, here’s a guy who has to be as raucous and as violent just to match the wrestling and the punk rock and Maggie and Hopey. And then, of course, there’s Isabel the witch lady, where you physically change her size. Now, Gilbert, you’re more inclined to see someone like the IRS collector who dresses in a gorilla suit in “Girl Crazy” or even the forest people in “Scarlet by Starlight,” and, of course, the representation of them in the sequel to that story. So to what degree do you feel that this transgressive behavior, this extremity, needs to be predicated in reality? How important is it to stray from real behavior? And how important is it to keep it real? How do the two of you deal with things that are almost hyperreal in service of a story?

Gilbert Hernandez: Well, for me — even if I want to do a story about scientists from the future in the forest and those animal people living with them — for that kind of story, you balance how much is going to be a part of us there and then what it’s going to be like in the future. It’s a bit of a balance. And so I was dealing with scientists and these forest creatures. So for that story, I just felt like there should be a human connection in it. Like some real sympathy for the forest people. The forest people didn’t know what hit them and the scientists could care less about them. But there’s that superficial attraction one scientists has for one girl. And then I’m toying with the whole fetish aspect of that furry thing. The fans of that sort of thing are called furries. They have this fetish for sexy furry animals. I’m getting into trouble here. And so naturally I drew the forest girls as sexy as possible. So that would trip up the reader and feel really weird about being attracted to her. But at the same time, there’s that on the surface. There’s that going on. But it’s important to have the human element within those stories, that being the most important thing.

Gilbert Hernandez: Well, for me — even if I want to do a story about scientists from the future in the forest and those animal people living with them — for that kind of story, you balance how much is going to be a part of us there and then what it’s going to be like in the future. It’s a bit of a balance. And so I was dealing with scientists and these forest creatures. So for that story, I just felt like there should be a human connection in it. Like some real sympathy for the forest people. The forest people didn’t know what hit them and the scientists could care less about them. But there’s that superficial attraction one scientists has for one girl. And then I’m toying with the whole fetish aspect of that furry thing. The fans of that sort of thing are called furries. They have this fetish for sexy furry animals. I’m getting into trouble here. And so naturally I drew the forest girls as sexy as possible. So that would trip up the reader and feel really weird about being attracted to her. But at the same time, there’s that on the surface. There’s that going on. But it’s important to have the human element within those stories, that being the most important thing.

Correspondent: But you also twist that exploitative quality on its head when you have, of course, the massacre later on in that story. It seems to me that you almost want to play with the idea of exploitation while simultaneously give into various transgressive behavior and so forth.

Gilbert: Well, I just through a bit of ugly reality in the end that, yes, even though the humans are hanging out with the forest people and they treat them relatively well and everybody’s getting along on that end, there’s that drop inside a lot of people that the moment they get the opportunity to exploit people, they’ll do it. That’s more of a criticism of people than animal creatures. (laughs) Cat people.

Correspondent: Well, Jaime, how does this transgressive work for you? I mentioned some examples at the head of that last question. How much do your characters have to be steeped in reality? And when do you feel the need to stray from it?

Jaime Hernandez: When I’m bored with reality.

Correspondent and Gilbert: (laughs)

Jaime: And seriously when I just want to have fun and goof. Like that story about Izzy growing big. I just wanted to throw a big curveball just for the hell of it and see how it would fly with the reader. And I don’t know why. But when I’m doing that, I’m really not worried about ruining the reality of it. Maybe because it’s just something I grew up with in comics. That the real life and fantasy go together. Like I said, it’s all just having fun and just goofing. But I do have the responsibility of keeping the reader there. I mean, making it real for the reader.

Jaime: And seriously when I just want to have fun and goof. Like that story about Izzy growing big. I just wanted to throw a big curveball just for the hell of it and see how it would fly with the reader. And I don’t know why. But when I’m doing that, I’m really not worried about ruining the reality of it. Maybe because it’s just something I grew up with in comics. That the real life and fantasy go together. Like I said, it’s all just having fun and just goofing. But I do have the responsibility of keeping the reader there. I mean, making it real for the reader.

Correspondent: But on the other hand, I look at a story like “Browntown,” which deals with sexual abuse and some very heavy topics, and I say to myself, well, I have to ask both of you — and also in “Farewell, My Palomar” — do you think that comics really need to grapple with this extreme heft in order to really matter as a medium? Are there any areas emotionally that you have not tapped and you really see Love and Rockets going further as? It has to be grounded in reality in some way, don’t you think?

Jaime: Right. Okay, so with a story like “Browntown,” there was no room for goofing. Because this is serious stuff. And I wanted to tell a real story that, tragic or otherwise, it was just really serious. And I didn’t want to almost make fun of it. Because it’s a serious issue. When I go there, I get really serious and there’s no room for goofing. In the case of Izzy growing into a giant, no one was getting hurt. So it was fun. Everyone got to go home and live their normal lives after that. But in “Browntown,” this was serious stuff. And I’m not going to mess with it.

Correspondent: So there’s an inevitable emotional filter you will have to apply, depending on the story. Depending on how people are going to get hurt or not.

Jaime: Yes. I only goof when it’s safe.

Correspondent: Well, what about you, Gilbert? Do you feel the same way? That a certain emotional tone requires a certain narrative filter to a story? That you have to be explicitly serious or explicitly ridiculous or fun in order to actually pursue a story? How does this work for you?

Gilbert: Sure. It’s the same thing. Like he said, he’s dealing with an aspect, an unfortunate aspect, of childhood that’s real for some people. All of a sudden, our brain goes into that mode. This is going to be told this way. I’m going to leave all the goofy stuff out and all the distractions out of it. Because this is how the story’s told. Even though, uncomfortably, this is still an entertaining story. You know, he wants to tell it as a story as you’re reading the story. It’s not a lesson being clobbered over your head. This is a story about characters, but it reflects on a problem that happens to children. So I approach it the same way. I have done serious things like attempted suicides in goofy stories. And I didn’t think that was right. I thought, “That’s something I don’t want to do anymore.” Because that was when I was learning. I was learning to tell stories. And in one of the first stories I did, I decided to have a guy attempt suicide. But it was in a science fiction story. And I got that uncomfortable feeling. Well, yeah, the reader looks at it like “Oh, it was a very shocking scene.” And I thought, “Well, it should have been about something. Not just gorillas from outer space or whatever.” That’s the problem I have with mainstream comics. Because they’re always trying to elevate the superhero by having drug problems and suicide attempts and stuff. And I just think that’s not where I’m at. That’s not where I want to read that. I mean, I suppose there are good stories about that in a Batman comic. But it makes me uncomfortable to read it that way. I kind of just miss the seriousness of it. Because it’s a guy in a bat suit in it.

Correspondent: Yeah. Are there any other stories that the two of you regret doing? That you would have done differently? Along these lines that you were just learning and you didn’t really understand the gravity of what that story was trying to say. Any other examples?

Jaime: Nothing really earth shattering. But there’s parts of “The Death of Speedy [Ortiz]” that I look back at, that I could have just put a little more into it. When I did it, it felt right. Years later, down the road, I look back at it and I go, “Well, maybe I could have explored this more on this part.” And then there’s a part of me that goes, “No.” But it’s been done. It’s been over. If I want to correct it, do it in a different story.

Correspondent: Is there any specific emotional terrain that the two of you have not tapped and perhaps would like to tap or would like to try? Or that is just purely verboten?

Gilbert: You know? I don’t know what that would be. It’s not there yet. We usually discover as we’re formulating a story. As we’re working on a story that’s going to build. That’s when it comes. It’s hard to think of that ahead of time. For us. Or for me at least.

Jaime: Yeah. Same here. Let’s say I’m doing a Maggie story. It’s going a certain way. And then I start to think about some serious issue. And I say, “Well, what if I turned it into this?” And I go, “Well, it’s not…it wouldn’t fit.” I would have to think about it harder. I would have to write around it. I couldn’t put the thing just…blam. All of a sudden in a story. Maggie’s having fun eating lunch and then something tragic happens. And all of a sudden, it’s wait a minute. Wait a minute. No, no. I would have to write around the tragedy instead of just throwing it in any old time.

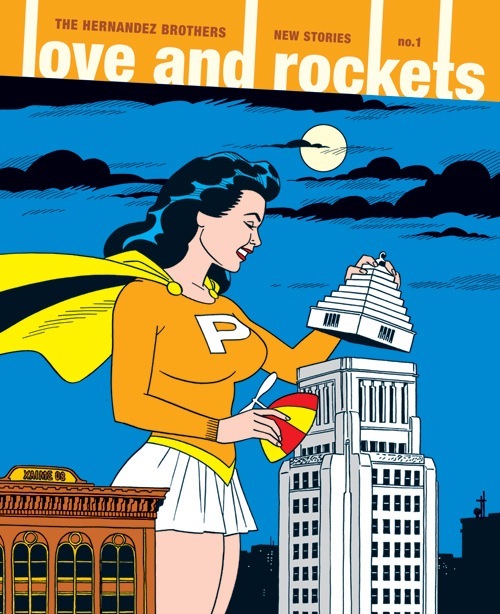

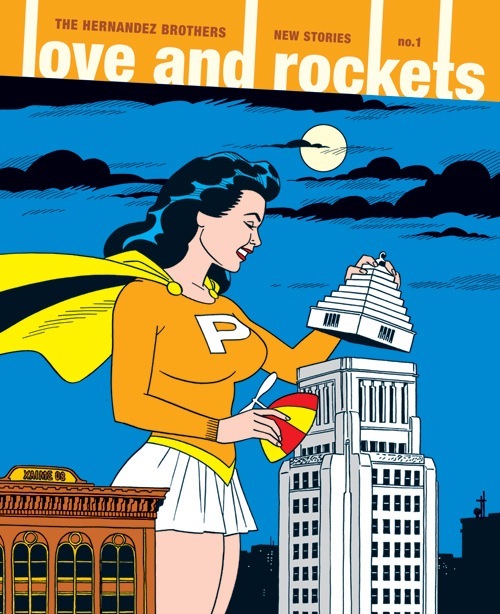

Correspondent: Well, both of you have resisted superheroes and referring to the comic book industry for a long time until recently. Penny Century finally gets her wish to be a superhero in the early portion of the New Stories. And I’m wondering why you resisted the whole superhero, comic book, self-referential notion for so long and why you would inevitably succumb to that impulse to portray it in Love and Rockets.

Correspondent: Well, both of you have resisted superheroes and referring to the comic book industry for a long time until recently. Penny Century finally gets her wish to be a superhero in the early portion of the New Stories. And I’m wondering why you resisted the whole superhero, comic book, self-referential notion for so long and why you would inevitably succumb to that impulse to portray it in Love and Rockets.

Jaime: I just didn’t want to do superheroes anymore. Seriously, I just wanted to tell more real life stuff. I thought stuff I had seen in my life was much more interesting to me. And a lot of it was not being seen in comics. And I kind of took advantage of that. And I kind of outgrew the superhero thing by the time Love and Rockets came. So by the time I did the Ti-Girl story, I just wanted to have fun with my own superhero comic.

Correspondent: The allure just kind of came back for some reason.

Jaime: Yeah. It was just for fun. I said, “Hey, I’m going to do a superhero comic. And I’m going to follow through to the end and see how it turns out.” Just for fun. Like that’s what I want to do right now. Gilbert always talks about this. That Love and Rockets has always been a comic book. He could explain this better. But it’s a comic book and whatever we want to put in there, we put in. Whatever interests us. So it’s like, “Whoa! You did a really serious true life adventure. Now you’re doing superheroes! What the hell is that about?” Nothing. Other than I just wanted to a superhero story the next time.

Gilbert: And we don’t try and elevate the superhero thing in Love and Rockets. Superheroes are a fun affectation. They’re just about fun and doing nutty stuff. And if you have some characterization in there and some pathos, there’s nothing wrong with that. That makes a story, you know? But we never think — like in the new Dark Knight Rises movie, we don’t think, “Well, to elevate this, we must eliminate Batman.” He’s in it for fifteen minutes in a three hour movie. You know, I came to see a Batman movie! Where’s his car? Where’s the Batcycle? “No, no, no, this is better than that!” Well, why do I want to see something better than that? I wouldn’t go see this stupid cop movie if Batman wasn’t in it. I’m serious. This is how I feel. The stuff doesn’t need the elevation. It goes back to the movie Greystroke, with Tarzan. It was a flop. Because it wasn’t about frickin’ Tarzan. “Oh, here’s the serious Tarzan movie. Let’s get rid of Tarzan and what he does.” And this is this dumb elevation that they do in mainstream comics, where they’re trying to elevate superheroes because they just can’t let go of Batman.

Correspondent: Superheroes are inherently silly.

Gilbert: Yeah. Or fun. Or adventure characters. That’s okay with me. I’m okay with Star Wars being about nothing but action adventure. Indiana Jones. The new Avengers movie was a success because it was a matinee film about the Hulk being funny and all this goofy stuff going on. It was a lot of fun. But then they try to elevate the stuff. And that’s what keeps me away from mainstream comics. Well, here’s the new Batman comic. But we elevate it to the drug war or serious crime stories. And I go, “Okay, but where’s Batman? Where is he doing stuff?” Batman does stuff. He doesn’t want to constantly mope. He’s in costume to do stuff! So, anyway, that aside, having superheroes and doing all that stuff — Jaime’s just doing superheroes to be fun and it’s part of our comic world. I like to think of Love and Rockets as a comic store with a lot of back issues. That’s what Love and Rockets is.

Correspondent: How much does this idea of elevation plague Love and Rockets today? I mean, in recent years, comics have become this supercommodified, maintream, pro-geek, “geek is the mainstream now” type of situation. How has this affected Love and Rockets? And how has Love and Rockets over the years been affected by economics? In terms of commercial forces. Has this really been as much of a consideration? Have there been certain storylines and characters that audiences have rejected or had to make adjustments for? Anything like this?

Jaime: We really don’t think about that that much. I mean, we just do our comic and hope it won’t be bumped off the shelf. Serious. It’s that simple. I mean, we just want to do comics that we think are good and have our share of the comic store. It may be naive of me, but I really don’t think about what’s going on around me when I am doing my comic. It’s just me and my comic, and I’m just happy that I’m able to do the next issue without starving.

Correspondent: Yeah. Well, how long during the Love and Rockets run were you doing this with other jobs and so forth? And what did you do to make sure that you got your pages in for the next Love and Rockets issue over the years? When you were doing simultaneous employment? Or has it pretty much been full-time most of the way?

Jaime: Right. Well, there was a time when we were starting the comic that it wasn’t really going anywhere financially. So I had to get a job as a janitor on the side. But then when Love and Rockets kinda started taking off and I started going, “Hey! I can support myself with this!” — because I was young and all I needed was an apartment and maybe a car. And just taking care of myself. I had no responsibilities. So it was easy to live pretty cheap with Love and Rockets in the beginning. And I was able to quit that dumb janitor job.

Correspondent: Roughly around when were you able to quit the janitor job?

Jaime: Mid-’80s. Like about three years into Love and Rockets. And I realized, “Hey, I can afford my cheap apartment. Hey, maybe I can even buy a car!” And stuff like that. And as I got older, Love and Rockets started to sell more. And I started to get more responsibility. I got married. And I started to think like a grown-up. But luckily, Love and Rockets was helping me get there. We were both growing together. So, like I said, in the carefree days, when we didn’t have any money, I didn’t care. I was just young and carefree.

Correspondent: Has the influence of responsibility and money adjusted your freedom on Love and Rockets to a certain degree? Or have you both felt relatively free beside responsibility?

Jaime: No. Beside responsibility, I’ve always kept Love and Rockets in its own safe pocket.

Correspondent: Compartmentalized.

Jaime: Yeah. Yeah. No matter which way my life was changing, whether I needed to buy a house or whatever, or raise a child or something like that, I always was able to keep Love and Rockets separate from that. I would be a dad and a husband, and then I would go away to my room and then I was the comic artist. So Love and Rockets, as far as art-wise, has always been left alone. I’ve always made sure that Love and Rockets was able to flourish artistically. Because nothing else could interrupt it.

The Bat Segundo Show #490: Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez (Download MP3)

This text will be replaced

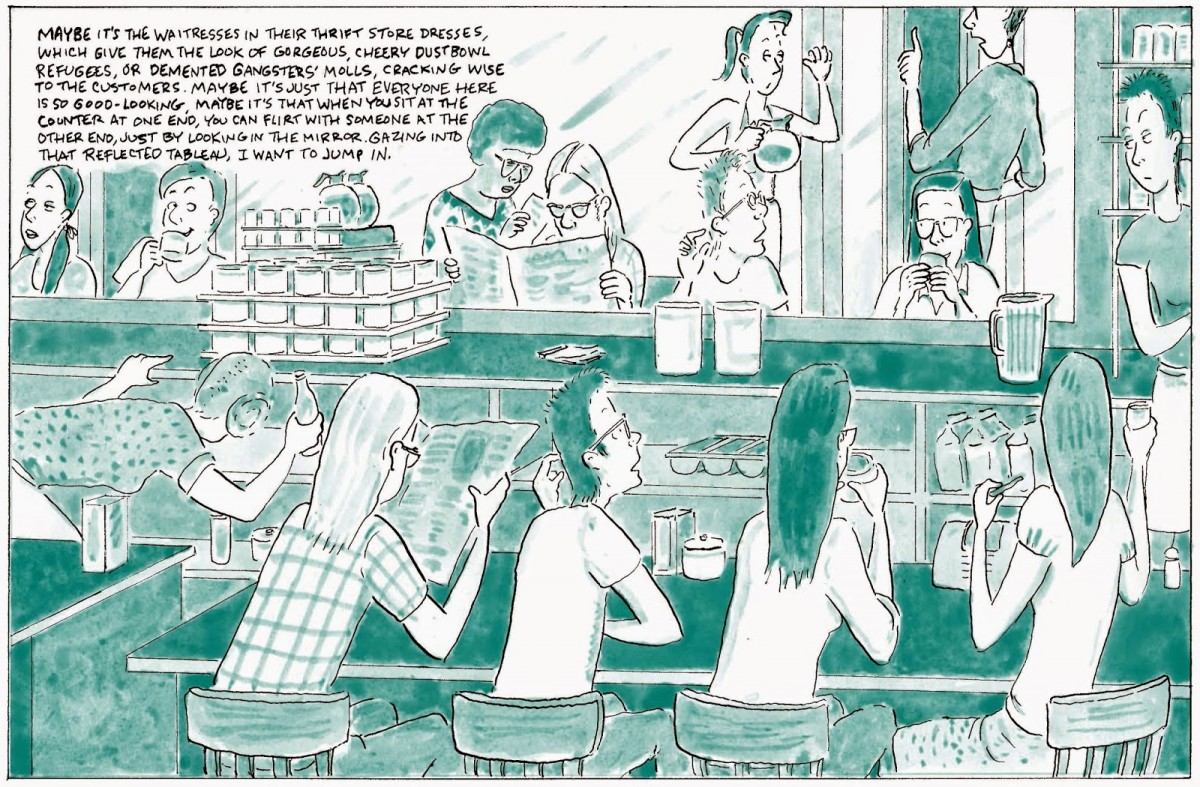

This graphic novel tells the story of Corrina Park, a young woman who works in an advertising agency. There is nothing interesting or unusual about her, unless you believe the occasional pilfering of a magazine from a convenience store to be jaw-dropping criminal mayhem. She complains about an unfulfilled creative life. She spends her evenings in a spacious apartment guzzling down wine and watching television. She listens to her boss quote Khalil Gibran while he steeples his fingers in the hackneyed manner of a corporate stooge smuggled from behind the arras at the last minute. While I was very fond of Corrina’s hissing cat (and what does it say that the only real character with any personality in this dull and pandering volume is an animal?), I could not find any open nook in my warm and expansive heart for this extraordinary listless protagonist. Corrina is no different from millions of young bourgie aspirants whinging throughout North America. If I wanted this kind of vanilla and unadventurous narrative, I’d spend two insufferable hours being barraged by other people’s First World problems at the Whole Foods overlooking the Gowanus Canal.

This graphic novel tells the story of Corrina Park, a young woman who works in an advertising agency. There is nothing interesting or unusual about her, unless you believe the occasional pilfering of a magazine from a convenience store to be jaw-dropping criminal mayhem. She complains about an unfulfilled creative life. She spends her evenings in a spacious apartment guzzling down wine and watching television. She listens to her boss quote Khalil Gibran while he steeples his fingers in the hackneyed manner of a corporate stooge smuggled from behind the arras at the last minute. While I was very fond of Corrina’s hissing cat (and what does it say that the only real character with any personality in this dull and pandering volume is an animal?), I could not find any open nook in my warm and expansive heart for this extraordinary listless protagonist. Corrina is no different from millions of young bourgie aspirants whinging throughout North America. If I wanted this kind of vanilla and unadventurous narrative, I’d spend two insufferable hours being barraged by other people’s First World problems at the Whole Foods overlooking the Gowanus Canal.

Gilbert Hernandez: Well, for me — even if I want to do a story about scientists from the future in the forest and those animal people living with them — for that kind of story, you balance how much is going to be a part of us there and then what it’s going to be like in the future. It’s a bit of a balance. And so I was dealing with scientists and these forest creatures. So for that story, I just felt like there should be a human connection in it. Like some real sympathy for the forest people. The forest people didn’t know what hit them and the scientists could care less about them. But there’s that superficial attraction one scientists has for one girl. And then I’m toying with the whole fetish aspect of that furry thing. The fans of that sort of thing are called furries. They have this fetish for sexy furry animals. I’m getting into trouble here. And so naturally I drew the forest girls as sexy as possible. So that would trip up the reader and feel really weird about being attracted to her. But at the same time, there’s that on the surface. There’s that going on. But it’s important to have the human element within those stories, that being the most important thing.

Gilbert Hernandez: Well, for me — even if I want to do a story about scientists from the future in the forest and those animal people living with them — for that kind of story, you balance how much is going to be a part of us there and then what it’s going to be like in the future. It’s a bit of a balance. And so I was dealing with scientists and these forest creatures. So for that story, I just felt like there should be a human connection in it. Like some real sympathy for the forest people. The forest people didn’t know what hit them and the scientists could care less about them. But there’s that superficial attraction one scientists has for one girl. And then I’m toying with the whole fetish aspect of that furry thing. The fans of that sort of thing are called furries. They have this fetish for sexy furry animals. I’m getting into trouble here. And so naturally I drew the forest girls as sexy as possible. So that would trip up the reader and feel really weird about being attracted to her. But at the same time, there’s that on the surface. There’s that going on. But it’s important to have the human element within those stories, that being the most important thing.  Jaime: And seriously when I just want to have fun and goof. Like that story about Izzy growing big. I just wanted to throw a big curveball just for the hell of it and see how it would fly with the reader. And I don’t know why. But when I’m doing that, I’m really not worried about ruining the reality of it. Maybe because it’s just something I grew up with in comics. That the real life and fantasy go together. Like I said, it’s all just having fun and just goofing. But I do have the responsibility of keeping the reader there. I mean, making it real for the reader.

Jaime: And seriously when I just want to have fun and goof. Like that story about Izzy growing big. I just wanted to throw a big curveball just for the hell of it and see how it would fly with the reader. And I don’t know why. But when I’m doing that, I’m really not worried about ruining the reality of it. Maybe because it’s just something I grew up with in comics. That the real life and fantasy go together. Like I said, it’s all just having fun and just goofing. But I do have the responsibility of keeping the reader there. I mean, making it real for the reader. Correspondent: Well, both of you have resisted superheroes and referring to the comic book industry for a long time until recently. Penny Century finally gets her wish to be a superhero in the early portion of the New Stories. And I’m wondering why you resisted the whole superhero, comic book, self-referential notion for so long and why you would inevitably succumb to that impulse to portray it in Love and Rockets.

Correspondent: Well, both of you have resisted superheroes and referring to the comic book industry for a long time until recently. Penny Century finally gets her wish to be a superhero in the early portion of the New Stories. And I’m wondering why you resisted the whole superhero, comic book, self-referential notion for so long and why you would inevitably succumb to that impulse to portray it in Love and Rockets.

Bechdel: Oh, I think of that Dr. Seuss spread, which was a purely visually driven sequence. I’m talking about one of my favorite childhood books, which was Dr. Seuss’s Sleep Book.

Bechdel: Oh, I think of that Dr. Seuss spread, which was a purely visually driven sequence. I’m talking about one of my favorite childhood books, which was Dr. Seuss’s Sleep Book.

Correspondent: I wanted to get into the ineluctable autobiographical angle through a different mechanism. Interviewers, critics — they’ve all said, “Oh, well, Tomine is totally autobiographical.” But here, you are tempting fate again with the subtitle of the book: “prenuptial memoir.”

Correspondent: I wanted to get into the ineluctable autobiographical angle through a different mechanism. Interviewers, critics — they’ve all said, “Oh, well, Tomine is totally autobiographical.” But here, you are tempting fate again with the subtitle of the book: “prenuptial memoir.”

Correspondent: I should point out I’m not trying to insist that stretching [the truth] is necessarily a bad thing. I’m merely pointing out that memory, as we all know, is a fallacious instrument.

Correspondent: I should point out I’m not trying to insist that stretching [the truth] is necessarily a bad thing. I’m merely pointing out that memory, as we all know, is a fallacious instrument.

Correspondent: I think we should really clarify this for the record. I mean, the stripes on Mo’s shirt become more pronounced over the course of time. And they increasingly grew thicker during the course of the early ’90’s. And then sometime around 1995, they solidified into that absolute thickness that we have enjoyed for the last decade or so. I know there have been many Harry Potter jokes that you’ve thrown around. But you were there, of course, before Harry Potter.

Correspondent: I think we should really clarify this for the record. I mean, the stripes on Mo’s shirt become more pronounced over the course of time. And they increasingly grew thicker during the course of the early ’90’s. And then sometime around 1995, they solidified into that absolute thickness that we have enjoyed for the last decade or so. I know there have been many Harry Potter jokes that you’ve thrown around. But you were there, of course, before Harry Potter.

Correspondent: I wanted to also talk with you about your “Family History” strip. I mean, it’s probably the closest thing in this collection to a hip-hop montage. You have, of course, the many births with the common images. A mother — one of your ancestors — giving birth with the “UNNNNH!” And you have a marriage with the “I do.” The swathed baby who is being held up by the white hands. And the like. I wanted to ask why repetitive images, or a hip-hop montage, seemed the best way to approach your own particular past.

Correspondent: I wanted to also talk with you about your “Family History” strip. I mean, it’s probably the closest thing in this collection to a hip-hop montage. You have, of course, the many births with the common images. A mother — one of your ancestors — giving birth with the “UNNNNH!” And you have a marriage with the “I do.” The swathed baby who is being held up by the white hands. And the like. I wanted to ask why repetitive images, or a hip-hop montage, seemed the best way to approach your own particular past.

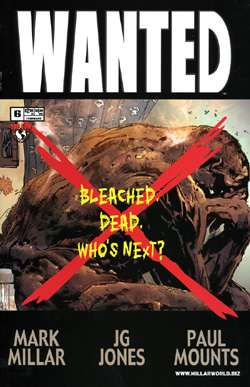

In the comic, Gibson is an unlikable narrator, who lacks the subtlety of another unlikeable narrator Millar wrote — Nazi Major Bauman in “Prisoner Number Zero,” which is one Millar’s best Wolverine stories. In Wanted, Gibson says, “I didn’t realize how much I hated the human race until I had the fuckers swanning around between my crosshairs.” This narration isn’t particularly antagonizing to the reader, but Gibson’s jokes about Down syndrome and babies born with spina bifida may be. Perhaps lazily, Millar titled the second issue, “Fuck You,” a charming name when considering some of the stale comic book in-jokes: in one scene, Mr Rictus, the super-supervillain (what do you call the villain in a story about supervillains?), kills the parents but spares their child, saying, “Leave him. With any luck, he’ll spend the next eighteen years training himself to avenge these idiots and give me someone interesting to fight when I’m an old man.”

In the comic, Gibson is an unlikable narrator, who lacks the subtlety of another unlikeable narrator Millar wrote — Nazi Major Bauman in “Prisoner Number Zero,” which is one Millar’s best Wolverine stories. In Wanted, Gibson says, “I didn’t realize how much I hated the human race until I had the fuckers swanning around between my crosshairs.” This narration isn’t particularly antagonizing to the reader, but Gibson’s jokes about Down syndrome and babies born with spina bifida may be. Perhaps lazily, Millar titled the second issue, “Fuck You,” a charming name when considering some of the stale comic book in-jokes: in one scene, Mr Rictus, the super-supervillain (what do you call the villain in a story about supervillains?), kills the parents but spares their child, saying, “Leave him. With any luck, he’ll spend the next eighteen years training himself to avenge these idiots and give me someone interesting to fight when I’m an old man.” The Ultimates embraced a decompressed narrative – what Millar called novelistic – where characters didn’t appear in every issue, and the plot developed at a pace that strengthened suspension of disbelief; Millar and Hitch created a superhero story that reads as how it would really happen. The decompressed narrative was hardly the revolution Millar claimed it was in commentary of the first volume of the series, but a style characteristic that made The Ultimates distinct from the typical mainstream superhero book. Millar set the series in today’s pop culture world, dropping references to Shannon Elizabeth, Jennifer Tilly, President Bush, Samuel L. Jackson, Johnny Depp, and Robert Downey Jr. (Downey was used in a joke about drug use.) Millar also addressed U.S. politics as the country fought its “War on Terror” and its war in Iraq. Thor resists working for the U.S.-backed Ultimates team because of the country’s military operations and oil obsession. When Thor complains to Nick Fury about the U.S. negotiating with the terrorists, Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch, Fury says, “Ain’t the first time the security services done deals with terrorists, big man.” Millar risked alienating readers who did not agree with his politics, though it’s unlikely he cared. The aforementioned Frank Miller and Alan Moore commented on politics in their most famous superhero stories.

The Ultimates embraced a decompressed narrative – what Millar called novelistic – where characters didn’t appear in every issue, and the plot developed at a pace that strengthened suspension of disbelief; Millar and Hitch created a superhero story that reads as how it would really happen. The decompressed narrative was hardly the revolution Millar claimed it was in commentary of the first volume of the series, but a style characteristic that made The Ultimates distinct from the typical mainstream superhero book. Millar set the series in today’s pop culture world, dropping references to Shannon Elizabeth, Jennifer Tilly, President Bush, Samuel L. Jackson, Johnny Depp, and Robert Downey Jr. (Downey was used in a joke about drug use.) Millar also addressed U.S. politics as the country fought its “War on Terror” and its war in Iraq. Thor resists working for the U.S.-backed Ultimates team because of the country’s military operations and oil obsession. When Thor complains to Nick Fury about the U.S. negotiating with the terrorists, Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch, Fury says, “Ain’t the first time the security services done deals with terrorists, big man.” Millar risked alienating readers who did not agree with his politics, though it’s unlikely he cared. The aforementioned Frank Miller and Alan Moore commented on politics in their most famous superhero stories. Millar has conquered one mainstream, and could conquer the larger one. His new series with John Romita Jr.,

Millar has conquered one mainstream, and could conquer the larger one. His new series with John Romita Jr.,

Correspondent: I’m wondering though if there has ever been an instance in your comic career, in which an editor has come to you and said, “Hey, Peter, the sales for this particular title are flagging. What can we do to raise things up?” Has this ever an influence?

Correspondent: I’m wondering though if there has ever been an instance in your comic career, in which an editor has come to you and said, “Hey, Peter, the sales for this particular title are flagging. What can we do to raise things up?” Has this ever an influence?

Correspondent: Here we have a military strip. But there’s no reference to Iraq. And I wanted to ask you about this kind of balance.

Correspondent: Here we have a military strip. But there’s no reference to Iraq. And I wanted to ask you about this kind of balance.

Correspondent: I’m wondering if certain artists may have changed their names because the comic book industry was considered a great calumny for many of these various artists and writers. Did you face a problem along those lines in tracking people down?

Correspondent: I’m wondering if certain artists may have changed their names because the comic book industry was considered a great calumny for many of these various artists and writers. Did you face a problem along those lines in tracking people down?

A free book along those lines wasn’t in my thick stack. And I doubt that many people who were in a comic shop for the first time will visit again and leave with an altogether different stack that contains a receipt. Reading an FCBD comic is like talking to the friend who tells you that he has an amazing story, but he doesn’t have the time to tell it to you right now. There were people in the stores, and FCBD deserves credit for this. But all these people ever got was a tease.

A free book along those lines wasn’t in my thick stack. And I doubt that many people who were in a comic shop for the first time will visit again and leave with an altogether different stack that contains a receipt. Reading an FCBD comic is like talking to the friend who tells you that he has an amazing story, but he doesn’t have the time to tell it to you right now. There were people in the stores, and FCBD deserves credit for this. But all these people ever got was a tease.

Brown: Well, it’s something. And I haven’t entirely figured out why. I mean, there’s something about when you know it’s true. There’s something about that honesty, that authenticity, that kind of heightens the impact of things sometimes. Which is why I’ve avoided doing more fictionalized autobiography. And sometimes I’ve thought about moving in that direction. And then it just doesn’t feel right for what I’ve done so far. But on the other hand, books — like some of the Bighead stuff — there are some very personal autobiographical elements sort of in there. So in a way, I kinda do it occasionally. In various half-assed ways.

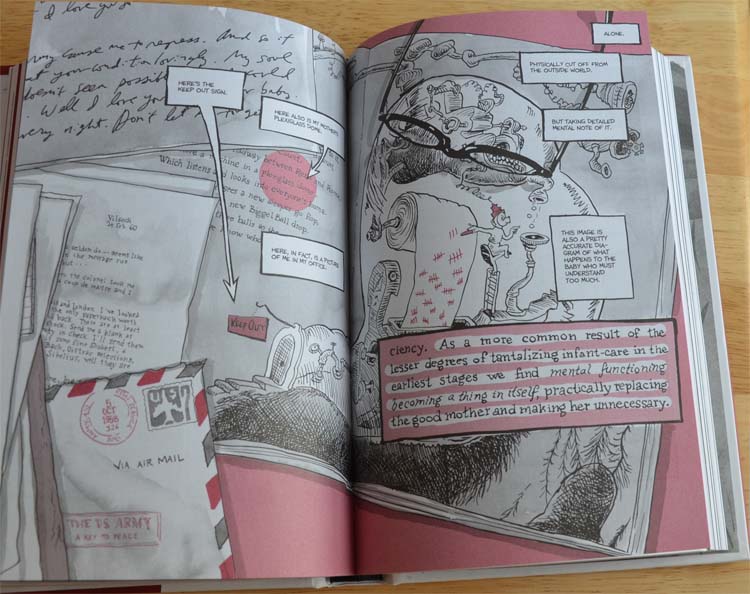

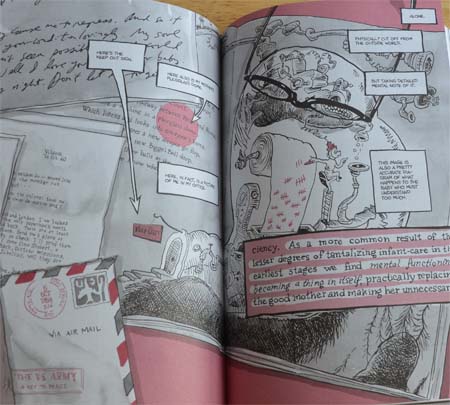

Brown: Well, it’s something. And I haven’t entirely figured out why. I mean, there’s something about when you know it’s true. There’s something about that honesty, that authenticity, that kind of heightens the impact of things sometimes. Which is why I’ve avoided doing more fictionalized autobiography. And sometimes I’ve thought about moving in that direction. And then it just doesn’t feel right for what I’ve done so far. But on the other hand, books — like some of the Bighead stuff — there are some very personal autobiographical elements sort of in there. So in a way, I kinda do it occasionally. In various half-assed ways. You might know Burns’s work from his advertisements or his illustrations for The Believer. But he’s best known as the writer and illustrator of the graphic novel, Black Hole, a compilation of his twelve-volume comic book. Burns worked on this over the course of ten years. And one of its remarkable qualities is the way that it remains remarkably consistent in its tone, despite the fact that Burns saw his two daughters grow up as he patiently put his work together. Black Hole depicts the story of a sexually transmitted disease that afflicts various teenagers in the Pacific Northwest. The work is very much a Rorschach test for the reader. One might infer a parable about AIDS or, if you wanted to get really reductive, innocence lost. Or it can be simply enjoyed as a dark tale of American adolescence gone awry.

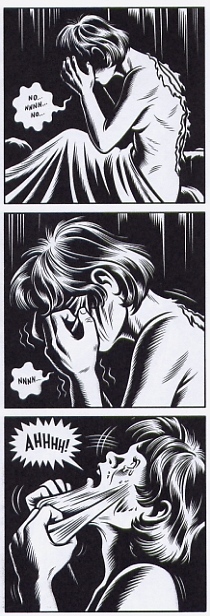

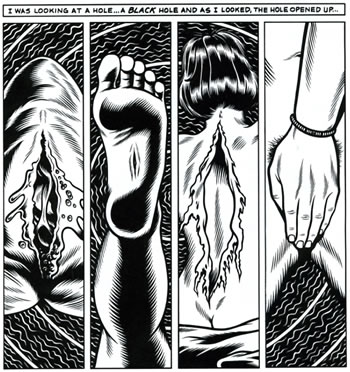

You might know Burns’s work from his advertisements or his illustrations for The Believer. But he’s best known as the writer and illustrator of the graphic novel, Black Hole, a compilation of his twelve-volume comic book. Burns worked on this over the course of ten years. And one of its remarkable qualities is the way that it remains remarkably consistent in its tone, despite the fact that Burns saw his two daughters grow up as he patiently put his work together. Black Hole depicts the story of a sexually transmitted disease that afflicts various teenagers in the Pacific Northwest. The work is very much a Rorschach test for the reader. One might infer a parable about AIDS or, if you wanted to get really reductive, innocence lost. Or it can be simply enjoyed as a dark tale of American adolescence gone awry. Correspondent: Okay. I also wanted to ask you about some of the anatomical close-ups throughout Black Hole. They remind me very much — in addition to the pustules and the various biological impediments that many of the characters have — it reminds me very much of the sort of World War II venereal disease films.

Correspondent: Okay. I also wanted to ask you about some of the anatomical close-ups throughout Black Hole. They remind me very much — in addition to the pustules and the various biological impediments that many of the characters have — it reminds me very much of the sort of World War II venereal disease films.