When I was 10, my favorite TV show was Window on Main Street. On CBS, it starred Robert Young, post-Father Knows Best, pre-Marcus Welby, as a widowed novelist in his late fifties who returns to his hometown, rents an apartment over one of the stores on Main Street and basically just hangs out and interacts with the townspeople, writing a new story about a different person every week.

The show was a flop and didn’t even last the whole 1961-62 season.

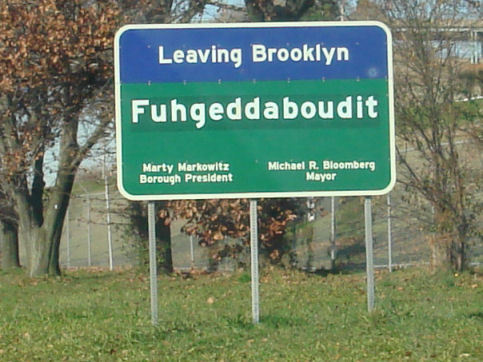

I’m writing this from the Starbucks in Dumbo, Brooklyn, sitting at a table in front of a window that overlooks Main Street. But Brooklyn’s Main Street is so short and nondescript that I lived the first 28 years of my life here and didn’t know it existed.

The neighborhood Dumbo didn’t exist back then either. For those who don’t know, and there’s no reason some of you should, it’s an acronym for Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass.

The Manhattan Bridge overpass is about a block in front of me; to my right, out the window on Front Street, I can see the Brooklyn Bridge overpass and cars going in both directions on the multilevel Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. Those on the upper level are going east to Long Island; those on the lower level are going west to America.

The most provincial people I’ve ever met in this country are lifelong New Yorkers.

Like Robert Young in Window on Main Street, I returned last summer for a temporary stay in my hometown. I’m a writer in my late fifties. Except I’m far from the only writer in Brooklyn, as Robert Young was in Millsburg. Sometimes it seems everyone in Brooklyn is a writer. Last fall the New York Times had an article by Sara Gran, a Brooklyn native like me, who now lives elsewhere, about the multitude of authors in the borough, which it termed “Booklyn.”

So I’d like to welcome Ed (odd, to welcome one’s host but this is Blogland as well as Brooklyn) to the ranks of Brooklyn writers. I don’t know if I really am one, though. I moved out at 28, and except for four short sublets in Park Slope, Sheepshead Bay, and the Williamsburg house where I’m currently living, I haven’t been a Brooklyn resident since 1979.

The past ten months have been an amazing experience. I recommend that everyone solve her mid-life (mid-life? I don’t expect to live to 112!) crisis by moving temporarily back to her hometown.

My friends and I at Brooklyn College in the early 1970s mostly couldn’t wait to get out of Brooklyn. We thought it was horrible in many ways, an embarrassing place to live. Nearly all of my friends moved away as soon as they could — to California, Florida (as I did), Boston, Seattle, Long Island, New Jersey, Manhattan.

The first line in the first story I ever published, in the undergraduate Brooklyn College literary magazine, paraphrased Norman Podhoretz in Making It: one of the longest journeys in the world is the one from Brooklyn to Manhattan.

Seven years ago this week, I was standing by the magazine rack in the Borders in Plantation, Florida, puzzled to read a line in the Publishers Weekly review of my book of gay-themed stories: “Grayson knows New York City, where many of these stories are set, inside and out.”

Huh? The title of the book was The Silicon Valley Diet and I thought I’d set the stories everywhere but New York: San Jose and San Francisco and Los Angeles, Miami and Gainesville and Tallahassee, Chicago and Philadelphia, Atlanta and Wyoming (yeah, I published a gay Wyoming cowboy story the same year as that other one).

But then I reread the book and saw that New York was everywhere: in the characters’ pasts and somehow even in the ones that never mentioned New York or Brooklyn.

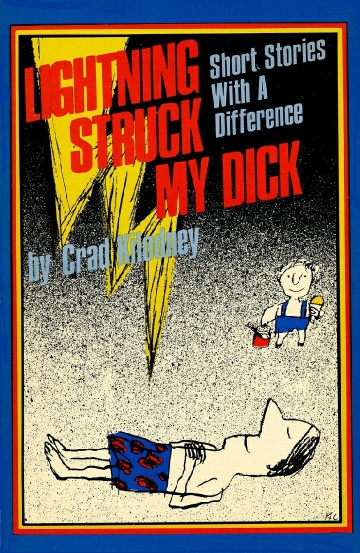

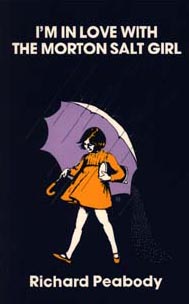

My last book was different: a deliberate Brooklyn book. The Kirkus review began, “The dynamic cityscape of Brooklyn serves as the backdrop in this” blah blah, and the Philadelphia Inquirer started with “Richard Grayson is a funny guy from Canarsie, Brooklyn…”

Actually, I’m from Flatlands, East Flatbush and Old Mill Basin — parts of Brooklyn where there are still very few writers. My childhood in the ’50s and ’60s wasn’t quite A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, not quite Last Exit to Brooklyn, and in my writing I’ve always tried, often unsuccessfully, to avoid strolling down the sticky paths of Stickball Street and Eggcreamery Lane.

When I was a kid, I used to collect Brooklyn bus transfers, which meant I had to ride every bus line in the borough. Since I’ve been back, I’ve been trying to replicate my childhood feat. Now, as then, I’m often the only white person on the bus. There’s a lot of Brooklyn that you don’t find in the mass of “Brooklyn” literature today.

Tomorrow I’ll be at my house in Apache Junction, Arizona, where the Starbucks on Apache Trail, not far from Old West Highway, has a hitching post. For horses. No horses here on Main Street: just a 24-hour parking lot, Fed Ex trucks, and a guy in a blue jumpsuit with the John Doe Fund logo sweeping up.

Because my arthritic knee is bad today, rather than walk to the nearest subway stop 6 or 7 blocks away, I’m going to take the B-25 bus. It goes along the Fulton Street Mall; over forty years ago I worked there in my uncle’s clothing store. I’ll get off by the G train stop next to the stage door entrance of the Brooklyn Academy of Music; over thirty years ago I stood there after a performance of Gorky’s Summerfolk to get the autograph of the play’s star, Dame Margaret Tyzack, whom I adored.

When she finally came out, I handed her my playbill and a pen and blurted out something about how much I loved her in The Forsyte Saga, The First Churchills and Cousin Bette. I guess I went on too long because this is what Dame Margaret said as she took my pen:

“Dear boy, it’s really very nice to hear all that, but you know, it’s sometimes good to know when to stop talking.”

Welcome to Brooklyn, Ed. I’m out of here.