[EDITOR’S NOTE: On April 2, 2013, I set out on a twenty-three mile “trial walk” from Brooklyn, New York to Garden City, New York, to serve as a preview for what I plan to generate on a regular basis with Ed Walks, a 3,000 mile cross-country journey from Brooklyn to San Francisco scheduled to start on May 15, 2013. This is the second of three trial walks and I have been forced to split it into two parts because so much happened. (You can also read about the first trial walk from Manhattan to Sleepy Hollow.) The project will involve an elaborate oral history and real-time reporting carried out across twelve states over six months. But the Ed Walks project requires financial resources. And it won’t happen if we can’t raise all the funds. But we now have an Indiegogo campaign in place to make this happen. If you would like to see more adventures in states beyond New York, please donate to the project. And if you can’t donate, please spread the word to others who can. Thank you! (I’ll be doing another walk on Friday, April 5, 2013 from Staten Island to West Orange, New Jersey and will also be live-tweeting the walk at my Twitter account.)]

Other Trial Walks:

1. A Walk from Manhattan to Sleepy Hollow (Full Report)

2. A Walk from Brooklyn to Garden City (Part Two)

3. A Walk from Staten Island to Edison Park (Part One and Part Two)

When you walk east in the early morn, there is no greater beauty than the sun slicing the last signs of night with the leisurely pace of a slow executioner. Dazzling white-orange light laps at the mandible of toothy square buildings. There are long stretches where you saunter ahead as blind as a blues virtuouso, with the sun swallowing the dark sky and spitting out a light blue. The white moon coughs out its last gasps as good tired souls who work graveyard shuffle homeward, swinging brown bags of breakfast. Onyx sidewalks brighten into drab square slabs and the ruddy beauty of Brooklyn brick shimmers out of the dark, beckoning humanity to bolt from bed and join the party.

I heard the jerky squeaks of rolling steel doors popped upward by small businessmen who had carefully tucked in their establishments the night before. There were twisted folding chairs and near dead portable alarms spewing feeble beeps in the street next to dead mattresses, all awaiting the pickup game of Tuesday morning’s trash collectors. There were people waiting at bus stops and dark trees pining for the fresh buds of spring. There was a man sitting on the sidewalk, his back angled against the building, his cane flat on the cement, and his right knee raised, as he smoked a thin cigarette and awaited a day of hustling that most heading to nine-to-five lives could not know. Just outside a Bed-Stuy deli, two older gents discussed how the neighborhood was changing. “More kids come from the Junction than they come from downtown,” said one. The hell of it was that the Junction was where I was heading.

“I don’t know how many people have ever seen or passed through Broadway Junction. It seems to me one of the world’s true wonders: nine crisscrossing, overlapping elevated tracks, high in the air, with subway cars screeching, despite uncanny slowness, over thick rusted girders, to distant, sordid places. It might have been created by an architect with an Erector Set and recurrent amnesia, and city ordinances and graft, this senseless ruined monster of all subways, in the air.” — Renata Adler, Speedboat

Adler also wrote about Brownsville’s “crushed, hollowed houses” and the “deserted strangeness” of a community cemented by tenants and funeral homes, although much of this has improved in recent years. Many young people who have no knowledge or interest in the city’s history before Bloomberg have taken to Adler’s 1976 novel — recently reissued by New York Review Books — as a handbook for life, much as Jonathan Franzen talked up Paula Fox’s Desperate Characters in a 1999 introduction (“I hoped that the book, on a second reading, might actually tell me how to live”). These are not the people who marvel at Broadway Junction, but you will find them hiding behind the latest issue of The Paris Review.

[haiku url=”http://www.edrants.com/_mp3/tw2-a.mp3″ title=”Conversation with Gary — Surface Transit HQ” ]

“I can’t really let you up.”

“Here,” said the woman from the executive office who had curled around the aperture leading into the security cage, “you cannot just go upstairs to the fourth floor…”

“That’s what I told him.”

“…and interview people.”

“As much as I would like to do that,” said Gary, the good-humored man keeping watch at Surface Transit Headquarters.

The woman from the fourth floor had come down because some recent packages had disappeared. There were people coming in for interviews. I certainly didn’t want to get Gary in trouble. But Broadway Junction’s twisted wonders had rekindled my desire to know more about transit. But I had been spoiled by the hospitality I received at Yonkers City Hall.

Gary had an intimate knowledge of the city. He has contributed several invaluable articles to Forgotten New York. We talked of Chase’s troubling tendency to gobble up old bank buildings and sully them with their dreaded branding. I mentioned Pat Robertson’s religious awakening on the edge of Clinton Hill and Gary corrected my pronunciation of Classon (the correct “KLAW-sun” has been uprooted by “CLAH-sun” — it’s a hard habit to break).

That morning, Gary was working as an “extra” for the MTA, which he’s been doing for eight years. Before that, he was a bus operator for twenty years until he was reclassified into security because of health issues. He works five days a week, has no complaints about the job, and sees about 50 to 100 people a day — nearly all of them transit workers. I asked about the craziest thing he’s seen on the job.

“A dead body floating in the Hudson River at the end of the line.”

But Gary’s great passion is keeping local history alive — especially the areas that few others appreciate. He suggested that I walk the southern end of Staten Island and I thanked him for his time.

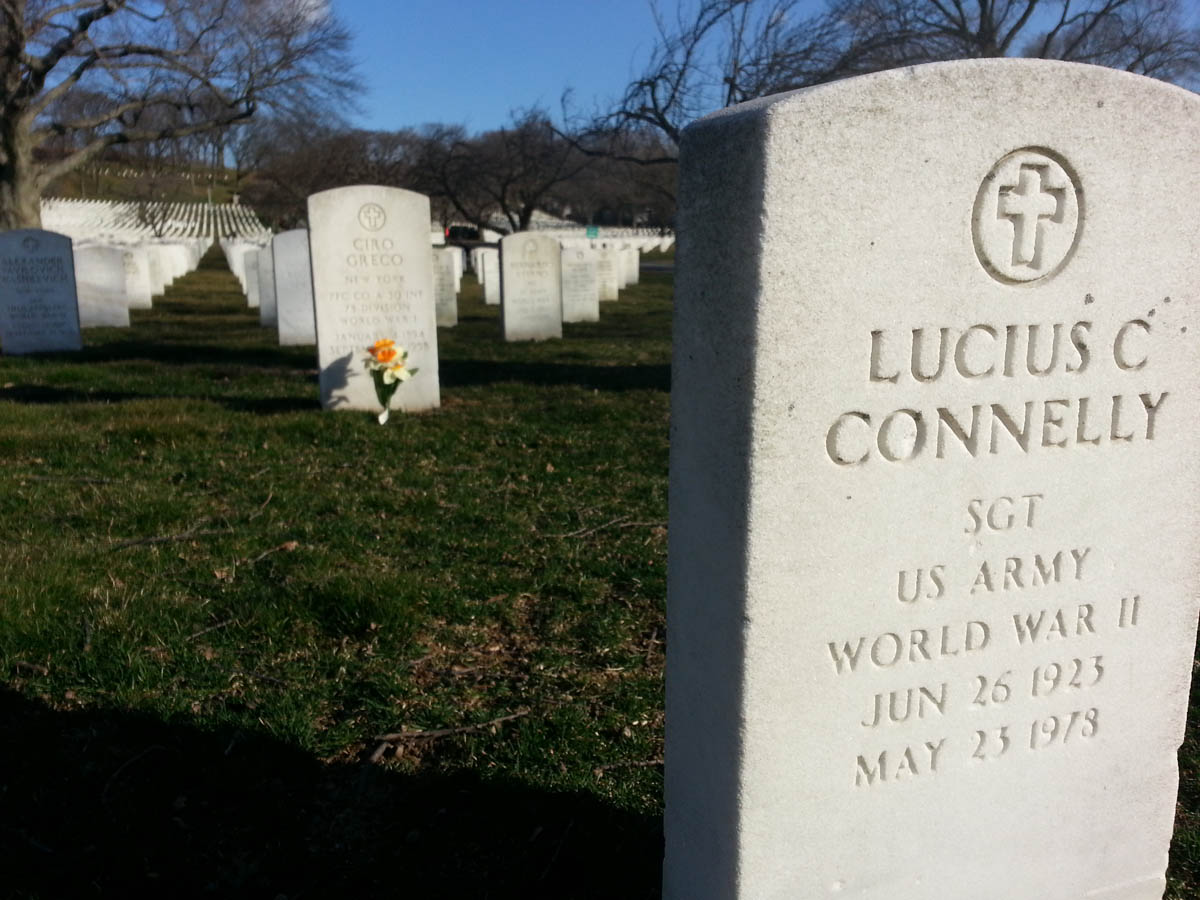

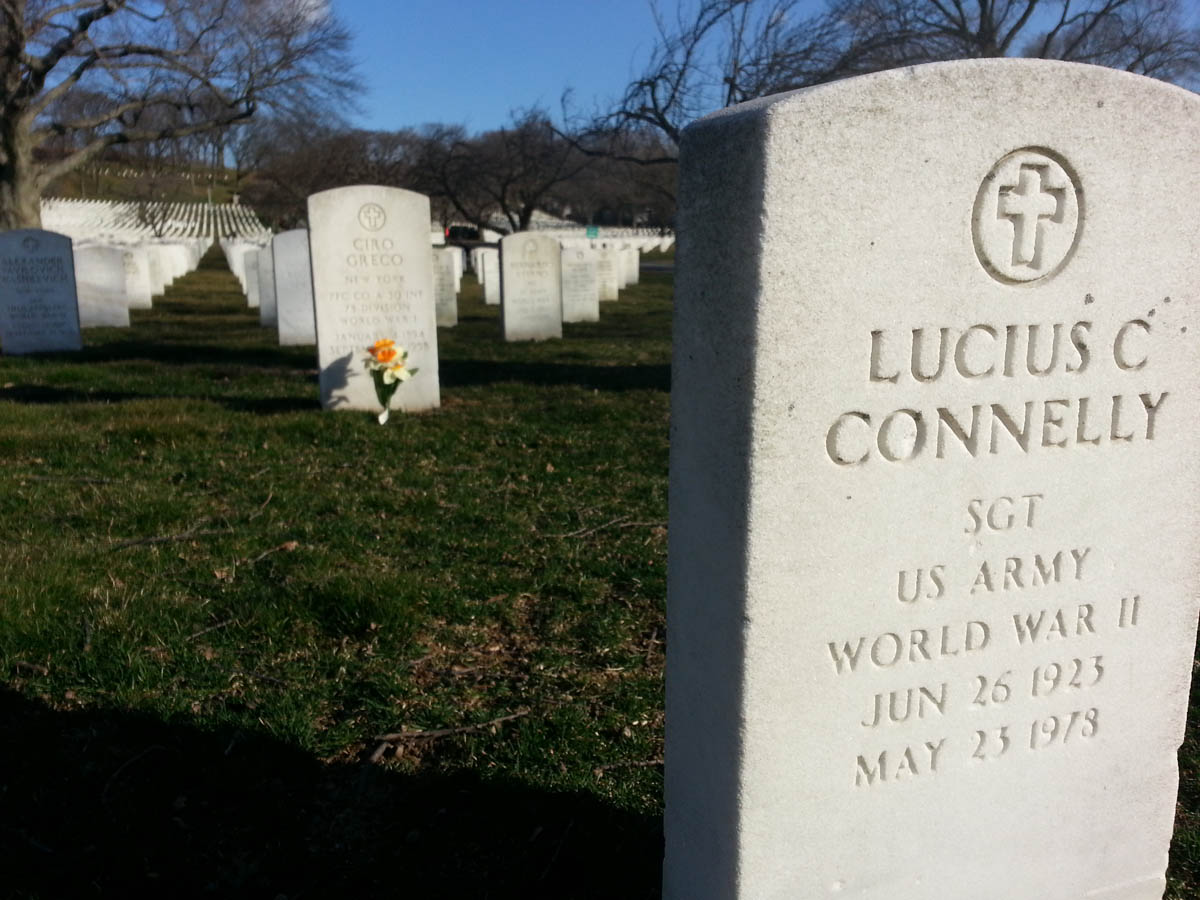

Gary’s talk of dead bodies led me quite naturally to Cypress Hills Cemetery. I learned a very hard lesson about visiting hours at Sleepy Hollow and figured that my interest in cenotaphs and tombstones should probably be tapped early for this walk. The veterans wing contained a notice banning firearms and weapons on the property under 18 U.S.C. § 930 — largely because the cemetery was considered a federal facility. No impromptu 21-gun salutes here.

Cypress Hills Cemetery is divided by the Jackie Robinson Parkway, which has faced a problematic history of poor planning and ancillary inadequacies. These design defects were very much in place as I made my way to the cemetery’s north end, where there was a paucity of passages across the parkway. I had hoped to see Mae West’s grave, which I knew was in the abbey. I had hoped that Ms. West would speak from the tomb. “Is that a joss stick in your pocket or are you happy to see me?” I had prepared a witticism for such an unlikely eventuality.

I found the abbey. The doors were locked. There were a few vans and some red machinery. Then I discovered a pair of knockers, which were round and delectable. Since I am somewhat perverse, I knocked. I halloed on hallowed ground. I shouted “You bad girl!” and cupped my ear to the door for a reply.

A car rolled up. A man rolled down his window. He worked for the cemetery.

I asked if it was possible to see inside the abbey for a few minutes. I was told that the workers were “on a break.” How long was the break? Of indeterminate length, but possibly fifteen minutes. And even then, I’d have to persuade them to jangle the keys. The unions must be pretty good at Cypress Hills Cemetery. I thanked the man and wended my way back to Jamaica Avenue.

I had lost time hoping to commune with Mae West. And because I still had a good fifteen miles to walk, I was forced to jet through Woodhaven. But I did make a southward drift to check out Neir’s Tavern, immortalized in Goodfellas. But I was more impressed with the breed-specific, machine-printed nature of many of Woodhaven’s residential signs. In the above case, I didn’t see any Rottweiler. I was somewhat disappointed that there wasn’t a dog who desired to tear me to shreds.

These morbid thoughts were percolating because I had eaten a light breakfast at a very early hour, which is not a strategy I would recommend for a 23 mile walk. I walked past costume shops with plus-size Supergirl costumes, a magnificent mural of a young woman in a yellow cardigan looking into a laptop, a lonely Donald Duck ride outside a supermarket, and an ancient post office. I walked past a bookstore that had been run by the late Bernard Titowsky. I walked…I walked…energy waning….I…

…emboldened by an early lunch, I walked through the long and dark tunnel beneath endless rail just west of Jamaica Station, past JFK and the AirTrain terminal, and into the brick sidewalks with young men shivering in hoodies before storefronts.

“We got top dollar shoes. Come inside and check it out! Come inside and check it out! All sizes available! Come inside and check it out! We got…”

But the wind chill was nippy enough to stanch the barkers. Although some men stood before shops, these hopeful words of commerce flowed into the street from speakers. The incantation “Come inside and check it out!” suggested something prerecorded, and I peered inside windows hoping to find majestical figures perched inside with microphones.

* * *

I arrived at Bellitte Bicycles at the beginning of peak bike season, which typically runs from March into October. This Jamaica shop has been owned by the same family since 1918 and it may be the oldest continuously operated bicycle shop in the United States. (The only authority for this claim is The New York Daily News.)

Every family member ends up going into the business and it’s been this way for several generations. I asked if there were any recalcitrant family members — perhaps a few stray Bellittes who shirked family destiny to become cutthroat corporate attorneys or HBO showrunners. But nobody resists. Bicycles are in the Bellitte blood. And if you don’t understand that, then you’re simply not a Bellitte.

The bicycle business is recession-proof. With rising gas prices and escalating MetroCard fares, people in the outer parts of the New York metropolitan area have sought affordable alternatives. And Bellitte Bicycles has been there to pick up the slack for some time. The shop has not seen a dip in sales throughout its history.

Nobody quite knows why Salvatore “Sam” Bellitte — the original owner of the shop — got into the bike business or why he was an early adopter. In the 1910s, Sam worked as a motorcycle and bicycle mechanic for another guy named Sam Hurvin, but there’s no trace of the mysterious Mr. Hurvin on Google. (However, I did find Hurvin in the 1920 U.S. Census.)

But the Bellittes have a very helpful book of photographs that you can look through if you’re interested in this history. They were exceedingly kind, run a very clean and well-organized shop, and are flexible enough with their stock to appeal to everyone from regular Joes to triathletes.

* * *

I was just outside Jamaica when the news jackals came at me. The crosswalk light was red. And I was confused when a CNN cameraman and some guy with wet cropped hair, sunglasses, and the sleaziest of smiles approached me with a mike. “Hey,” said the jackal with the sleazy smile, “do you know about Malcolm Smith?”

Yes. The white guy with glasses. Get him! He’s safe for our audience.

The jackal then offered a very condescending overview about Smith’s recent bribery scandal. I was bewildered, largely because the idea of asking random people in the street about their opinions on a major news story that only confirmed preexisting biases was not only lazy, but a missed opportunity. The ways that people live lives are far more meaningful and intriguing.

It was also comically unfathomable that I would be singled out as a local in a territory that was not mine.

“Actually,” I said to the jackals, “I may have a story for you.”

I told them about my walk, informing them that I was in the middle of a 21 mile* journey to meet an astronaut at the Cradle of Aviation Museum and that I had been walking there from Brooklyn all day.

“Oh,” said the jackal, “you’re not from the neighborhood.”

Then the jackals walked away.

I didn’t know if I could persuade a man who had nine spacewalks under his belt to give me a few minutes of his time. But I was too far into my walk to quit.

* * *

Part Two: Floral Park, keeping a racing pastime alive in Franklin Square, and meeting an astronaut in Garden City.

* — I did not know at the time that I would miscalculate the distance and that it would end up being 23 miles.

Correspondent: I’m wondering also about the Terri Schiavo narrative, because it does play in more later in the book than in the beginning of the book. Did you know immediately that there was this almost quasi-allegorical feel to that? Or did it start with the fact that you had Martin Miller in this coma?

Correspondent: I’m wondering also about the Terri Schiavo narrative, because it does play in more later in the book than in the beginning of the book. Did you know immediately that there was this almost quasi-allegorical feel to that? Or did it start with the fact that you had Martin Miller in this coma? Correspondent: Okay, well, if Davis and the donut girls was one of the key starting points, was this an imagined experience? Or was this drawn from anything specific that you observed? Because I am certainly not familiar with this phenomenon. (laughs)

Correspondent: Okay, well, if Davis and the donut girls was one of the key starting points, was this an imagined experience? Or was this drawn from anything specific that you observed? Because I am certainly not familiar with this phenomenon. (laughs) Correspondent: Going back to this issue of topography as a launching point, it’s reminiscent to me of Nabokov’s rule, where he basically said that he could not write a novel until he actually had a particular location. Likewise, in addition to this inspirational momentum, I wanted to first of all find out if this was a factor for you in terms of writing this. And it also leads into another question about Jarvis’s perspective, where she’s generally taking a small item and putting it into a larger neighborhood. For example, there’s a pack of cigarettes she observes. And she’s very clear in the way that she describes it as coming from a particular deli and how it was actually purchased and the like. So I wanted to ask you about this phenomenon. Was this a way for you to generate momentum in your book? You needed to get the lay of the land before the lay of the characters?

Correspondent: Going back to this issue of topography as a launching point, it’s reminiscent to me of Nabokov’s rule, where he basically said that he could not write a novel until he actually had a particular location. Likewise, in addition to this inspirational momentum, I wanted to first of all find out if this was a factor for you in terms of writing this. And it also leads into another question about Jarvis’s perspective, where she’s generally taking a small item and putting it into a larger neighborhood. For example, there’s a pack of cigarettes she observes. And she’s very clear in the way that she describes it as coming from a particular deli and how it was actually purchased and the like. So I wanted to ask you about this phenomenon. Was this a way for you to generate momentum in your book? You needed to get the lay of the land before the lay of the characters? After breakfast, I found myself offering an impromptu historical tour of Brooklyn, learning in media res that Grand Army Plaza at one point had a

After breakfast, I found myself offering an impromptu historical tour of Brooklyn, learning in media res that Grand Army Plaza at one point had a

Again, the great fun of the booths and barkers cannot be understated. One such booth was dubbed “Shoot the Freak,” where a young man was employed to dodge paintball pellets fired from gleeful rifle slingers. There was no apparent incentive to the participants — no stuffed animals, no kewpie dolls — other than the satisfaction of nailing a guy running around in a funny purple suit. It is difficult to fathom such a gleeful carny-style impulse at work at a Six Flags amusement park.

Again, the great fun of the booths and barkers cannot be understated. One such booth was dubbed “Shoot the Freak,” where a young man was employed to dodge paintball pellets fired from gleeful rifle slingers. There was no apparent incentive to the participants — no stuffed animals, no kewpie dolls — other than the satisfaction of nailing a guy running around in a funny purple suit. It is difficult to fathom such a gleeful carny-style impulse at work at a Six Flags amusement park.