[2021 UPDATE: I have since recanted this position. But I leave this essay up for any dubious historical value it may hold.]

On Monday night, I discovered quite by accident that a midlist author had blocked me on Twitter. Not unfollowed, but blocked. This had come after nearly a year and a half of mutual help and steady correspondence. In recent months, this author confided to me about his problems. I made several gestures to meet up with the author on his next trip into the city so that we could talk about this in person. I believed in his talent. I knew a few people who could help him out.

After I had interviewed the author before an audience, we pledged a get together. He didn’t respond for weeks. He had secured what he needed. Now I could be dropped. It was probably impetuous of me to conclude this, much less assume that the author was capable of responding to email or even following up on his many pledges while on the road. On the evening that the author next rode into town, the two of us exchanged hostile words through that woefully unsubtle and impulsive form of communication known as email banged out on smartphone keyboards. Neither of us came across very well. Shortly after this, the author’s wife, who had a much wiser head about the way men emote than the two foolhardy men here in question, sent a diplomatic email trying to find out what happened. I thanked her for her email and explained my frustrations, apologizing for my part in the exchange, and pledged a cooling off period. Weeks later, I discovered that the author had blocked me on Twitter. He had also blocked my longtime partner, who had no role in the dispute whatsoever.

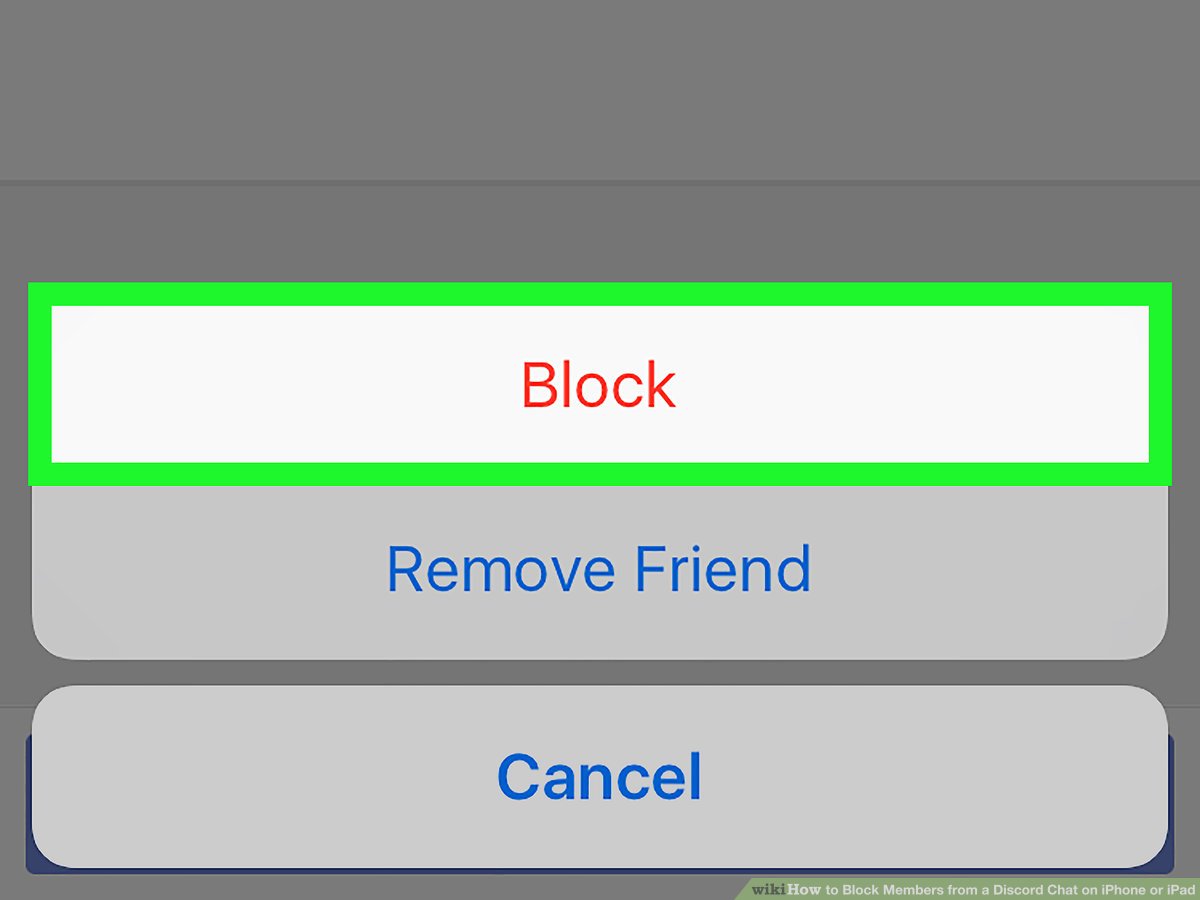

I know that I behaved badly and the reasonable email from the author’s wife helped me arrive at that conclusion. I also recognize that nobody is under any obligation to follow anybody. But isn’t blocking over the top? Pushing the online world’s answer to the big red button is something one reserves for a cyberstalker, a full-bore troll, a spammer, or a truly dangerous individual, not a former acquaintance that you had a vitriolic spat with.

Yet the power to block people on social media over pedantic offenses has encouraged many otherwise sharp blades to push down their capacity for tolerance and ratchet up the fear. It’s a remarkably contemptuous response to the paradoxical nature of existence. For who among us hasn’t uttered rash words or muttered moronic quips? The block button is free speech’s answer to the gun-toting libertarian who holes up in his bunker, claiming that he doesn’t need government services to put out the fires or stop crime or service the highways or take out the trash or maintain the sewers. It is an ideal that sounds noble in theory, but is precipitous in practice. As Jacob Silverman argued in Slate back in August, offense or disagreement doesn’t have to be toxic.

In writing this essay, I don’t wish to make the same mistakes that New York‘s Nathan Heller did two weeks ago, approaching this complicated subject from a privileged and blinkered position. Back in May, Richard Cooper pointed out how Twitter media bigshots shut down their critics. This was followed in October by a lengthy post from Neil Bomb’d about how comedians employed their fans to bully detractors in numbers. This week, Chris Brown and his followers attacked Jenny Johnson on Twitter with deeply misogynist remarks. There are also Laurie Penny’s ongoing reports about the sexual bullying of women and girls online, the IDF’s recent aggressive use of Twitter to foment ideological conflict, and sites which pilfer pictures from social media in the name of scummy extortion.

The block button is the very instrument which has permitted these many unpleasant online conflagrations to flourish. It is a poor and inefficient mechanism that has deigned to place judgment in the hands of the users, but that has mostly encouraged our worst instincts and clearly not learned from history. It was the hideous phrase “blocked for stupidity” which attracted Cooper’s notice. Bomb’d reports that a user named MissSpidey tried to report abusive users to seek understandable redress. She became suspended from Twitter for “aggressive blocking.” Not only does the block button incite users to feel anger and retaliate when on the receiving end, but it can’t even be properly used in its native mode.

I believe that getting beyond all this will involve either extirpating the block button from our social media interfaces or resorting to more enduring human qualities that don’t require any particular software platform. As I noted back in August, it isn’t an epidemic of niceness that’s the problem, but a paucity of kindness and respect. If we can stop erecting massive edifices that get in the way of conversations and we learn from the free flow that has permitted a thousand cat videos and a million animated GIFs to bloom, there’s a chance of improving how we communicate.

* * *

Before the block button granted every individual the power to stub out any vaguely offensive viewpoint from a timeline, there were comment moderators. The comment moderator had the thankless yet invaluable duty of sifting through tens of thousands of comments each month in an online forum, flagging highly offensive or disruptive remarks that went over the line. Not only did this system create a third party that arbitrated disputes and explicated motivations in a respectful and relatively neutral tone, but it permitted users and moderators alike to strike an acceptable compromise between preserving distinct voices and perpetuating a healthy community.

Lessons from 11 years of community (my SXSW 2011 talk) from Matt Haughey on Vimeo.

In a video adapted from his 2011 SXSW talk, Metafilter founder Matt Haughey smartly outlines some vital maxims he learned during eleven successful years of community moderation. He suggests that community moderators refrain from being overprotective. “I mean, we’ve come to the conclusion,” says Haughey at the 4:15 mark, “you know, putting up barriers when necessary, only after they’ve been permissive for years and years. And I like to think of this as a concert. You know, you don’t want your security at the front, between the band and the crowd, pushing the crowd back. That’s not really what you want moderators to be. You want them to be kind of part of it. Participants in it.” Haughey also mentions in the video that the burnout emerging from constant complaints from users causes moderators to turn into bad cops, losing sight of the initial reasons why they organized the community in the first place. Haughey also says it’s helpful to give users a forum to vent and offer feedback.

But as comment moderating power has shifted from third party mediators to individual users, the distinctions that retired community moderator Elliot Guest observed between someone who deviates from the accepted norm, someone who hasn’t read the full context and who enjoys tossing out acronyms like “tl:dr,” and someone who sets out to instigate chaos for chaos’s sake have become mangled. As individual users block with their emotions, anyone even remotely belligerent becomes a troll. Negative feelings perpetuate additional negative feelings. And instead of a thriving democracy, online community deteriorates into little more than a collection of volatile city-states perpetually at war with each other.

It didn’t help when many of the Web’s rosy pioneers encouraged the block button as it became a more prominent part of online existence. In 2010, Derek Powazek wrote:

I propose that blocking people on sites like Twitter or Flickr should not be interpreted as an insult. I propose that it’s simply taking yourself out of someone else’s attention stream.

If I block you on Twitter, my tweets no longer show up in your timeline. If I block you on Flickr, my photos no longer show up on your contacts page. In these settings, this is the only way for me to remove myself from your attention.

Not an insult? With all due respect, what could be more egomaniacal than Powazek’s “one strike” policy?

If you post a tweet that bothers me for any reason, no matter how small or petty, it’s extremely likely that you’ll do it again. It’s so likely, in fact, that I’m going to save myself the annoyance and just unfollow you now. After all, you’re not on My List of People I Must Be Okay With, and I’m not on yours. I’m just choosing to have one less brief annoyance in my day.

I’m bothered by all of this, but it would never occur to me to put Powazek on the same level as George Lincoln Rockwell. That’s as preposterous as forcing some drunken lout in a bar to vanish into thin air using a Samsung Galaxy and a pair of chopsticks. It’s simply beyond the laws of real world physics, yet faith in online simulacra has us thinking we can bend the rules. Well, it didn’t work for gamification advocates like Jane McGonigal and it won’t work for social media. The human spirit is too muscular and manifold to be packed into a digital valise.

Moreover, the willingness to write off some figure who tells us something we don’t want to hear, and to do this over a mere 140 character message, is nothing less than an irrational and unhealthy fear which fails to account for the distinct possibility that there may be some positive quality contained within the petty annoyances. It is a declaration against outside-the-box thinking, representing a growing incapacity to reckon with vital human realities or topics we may need to think about.

Nobody wants to be told, for example, that the global temperature could rise by 4 degrees Celsius as early as 2060, but it’s a very real consideration that even a neoliberal organization like The World Bank has warned against. Suppose that something like this or, for those who still think climate change is a hoax, the indisputable scientific fact that the carbon atom has six electrons is a petty annoyance for someone like Powazek.

At this point, the common fantasy expressed on Facebook and Formspring of being able to block people in real life takes on a more sinister and anti-intellectual quality. It becomes no different from a creationist attempting to block Darwin from being taught in the classrooms or an NYPD sketch artist resorting to racist stereotypes because he has blocked out the possibility that a suspect who killed three Brooklyn shopkeepers is some guy with a moustache. Perhaps most perniciously, it has the result of reducing thoughtful adults to oversensitive sixth graders plugging fingers in their ears and barking “La! La! La! I can’t hear you!” at every opportunity.

I’d like to think that most people, including the author I described at the beginning and me, are better than this. Online culture is disastrous in accepting people’s faults. It encourages a scorched earth mentality with a single click. What would happen if the people we disliked were allowed in our timelines? Perhaps if other people we trusted were retweeting and referencing these debauched or hopeless souls, we might reconsider our opinion. We might come to know them better, or at least as well as online communication will allow. We might see, as we often do when hanging out with somebody in real life, that one’s time on this earth is too short to roll out the howitzer over something small or petty. Kurt Vonnegut once suggested that the most daring thing for young people to do “is to create stable communities in which the terrible disease of loneliness can be cured.” I can’t think of a more deliberate cancer to court than blocking somebody over a stupid tweet. But until someone comes up with a better idea to manage the trolls, the button remains irresistible.