“I don’t see any need for arguing like this. I think we ought to be able to behave like gentlemen.” — Juror Four, Twelve Angry Men

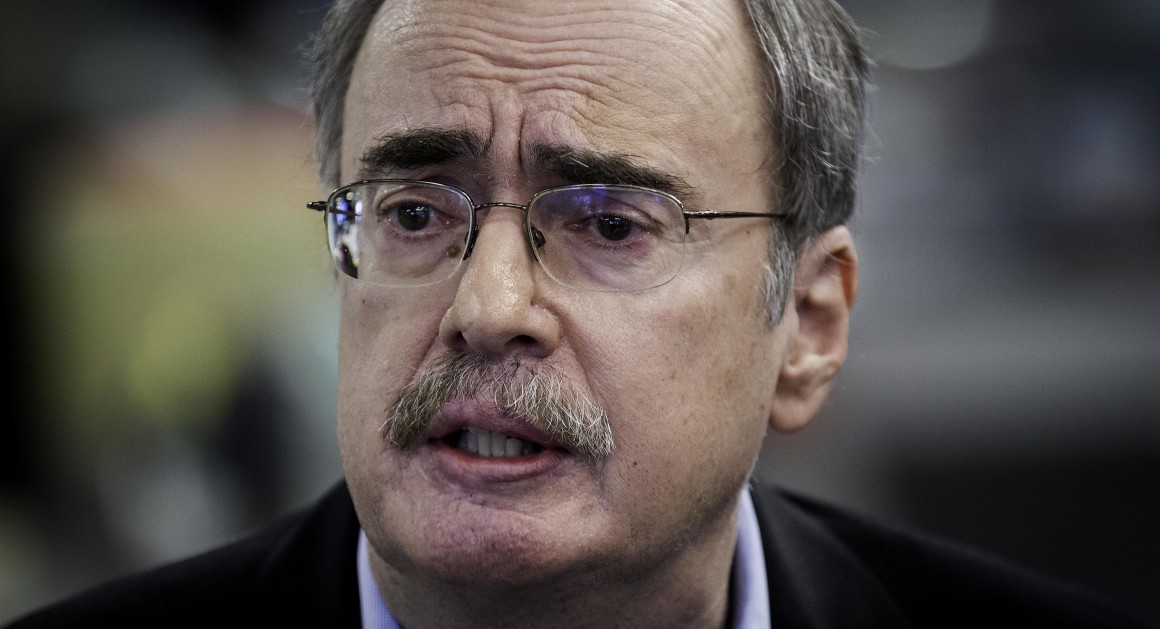

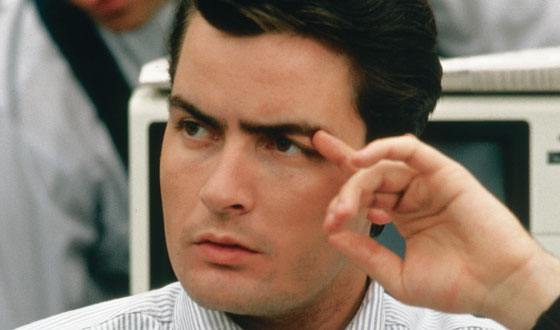

Scott Tobias is a 41-year-old man who lives in Chicago with a wife and daughter. In 1999, he started work at The Onion, where he became the film editor at The A.V. Club — a print supplement that is bundled with The Onion in eight cities. According to Quantcast, The A.V. Club has a global monthly online reach of 1.9 million unique visitors. Tobias also contributes reviews to NPR, whose ethical handbook specifies this high-minded guideline:

Everyone affected by our journalism deserves to be treated with decency and compassion. We are civil in our actions and words, avoiding arrogance and hubris. We listen to others. When we ask tough questions, we do so to seek answers — not confrontations. We are sensitive to differences in attitudes and culture. We minimize undue harm and take special care with those who are vulnerable or suffering. And with all subjects of our coverage, we are mindful of their privacy as we fulfill our journalistic obligations.

At the beginning of this week, this seemingly mild-mannered man, who had graduated from the University of Georgia with a bachelor’s degree in comparative literature and had worked on a Master’s degree in Cinema Studies at the University of Miami, devolved into a defamatory diablo on Twitter.

Over two and a half days, Tobias, who has nearly 15,000 followers, posted approximately forty-nine tweets which implied that a man, who has nearly 6,000 followers, had wronged him. Rather than participating in a civil and constructive dialogue, Tobias preferred arrogance and indecency and used his influence to vilify this man on Twitter before the man had a chance to see or respond to his tweets. Tobias never thought to contact the man by email until the wrongful insinuations he had put forth had propagated among his peers. That man was me.

As Richard Cooper has astutely observed, when a figure on Twitter climbs his way up the social hierarchy after racking up followers like a rabid pachinko addict, there’s the risk that he’ll develop a weird and entitled attitude against anyone sending him a critical tweet. And Tobias became just that: a small-time ochlocrat who hoped to shut me down because I had the audacity to question his stance on a tweet widely perceived as unthinkable.

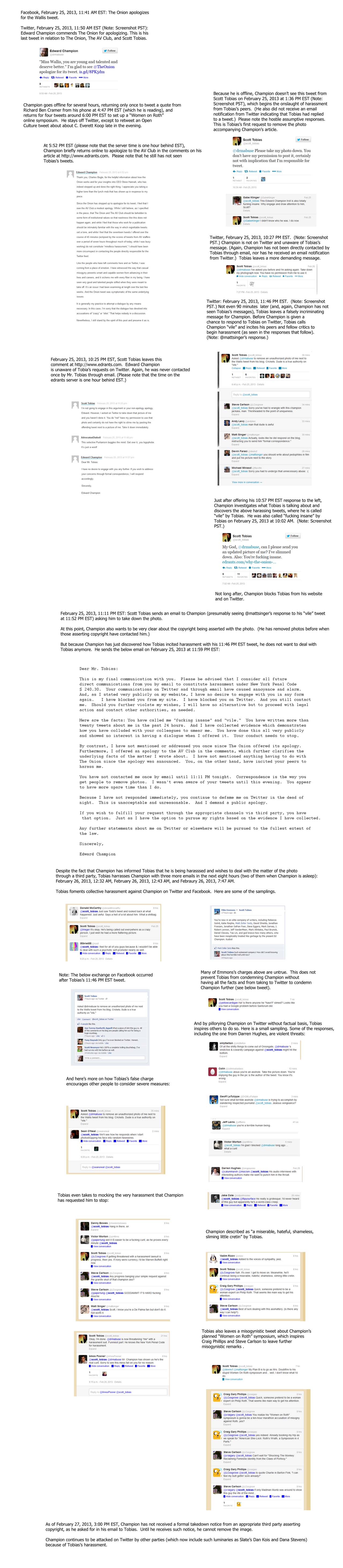

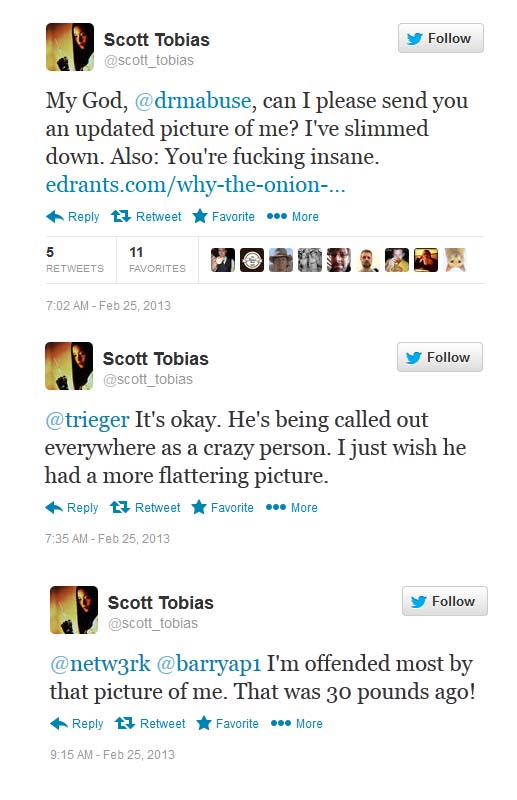

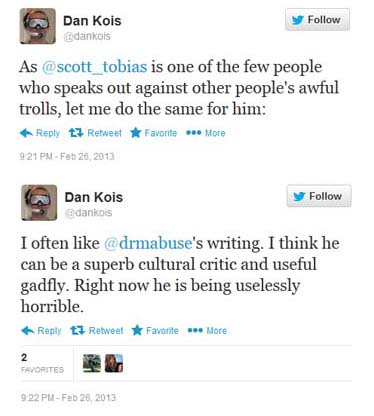

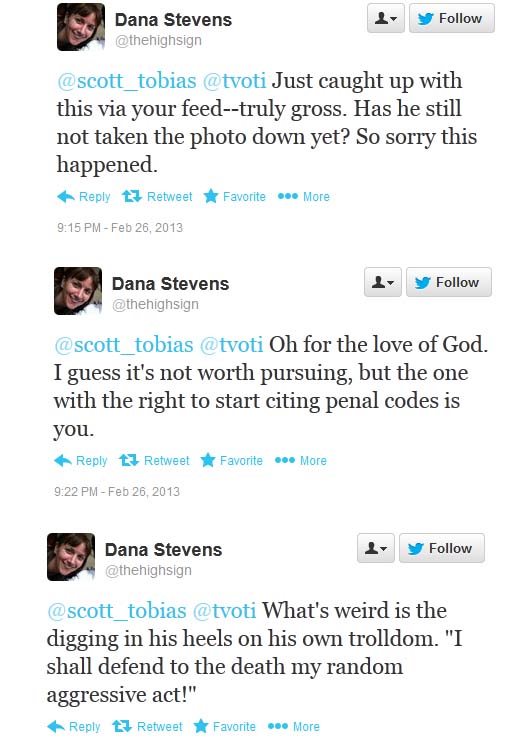

Tobias called me “vile” and “fucking insane” and “a miserable, hateful, shameless, sliming little cretin.” (The worst I had called Tobias was “spineless” when he would not answer a question.) He summoned the wrath of such cultural figures as Slate‘s Dana Stevens and Dan Kois, HitFix‘s Daniel Fienberg, and several others, who never thought to question Tobias’s position or investigate the facts. They preferred to feed Tobias’s blind and unthinking fury, which had emerged well after the underlying issue involving The Onion had been resolved. It came about because I had not removed a photo that was well beneath the mildly irreverent temperature set by The Onion in publishing such images as one featuring doctors hovering over a sickly Fidel Castro (published on February 26, 2013) or the infamous juxtaposition of 6-year-old murder victim JonBenét Ramsey (published on August 9, 2012). It came about because Tobias wanted revenge.

* * *

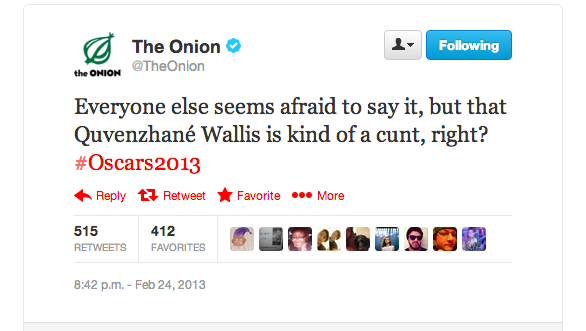

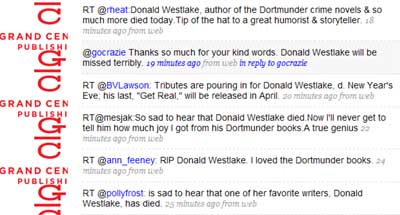

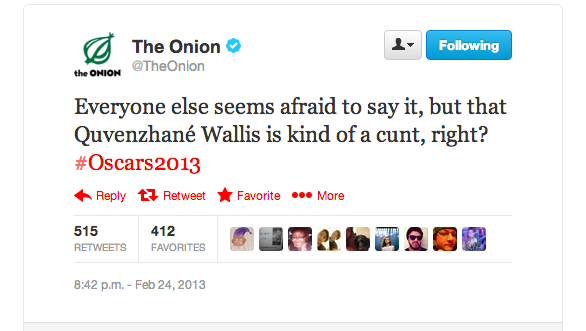

On Sunday night, The Onion had posted the above tweet during the Oscars ceremony. This thoughtless verbal assault on Quvenzhané Wallis, a nine-year-old actress nominated in the Best Actress category for Beasts of the Southern Wild, raised many hackles. The Onion deleted the tweet an hour later. Nobody at the time took responsibility.

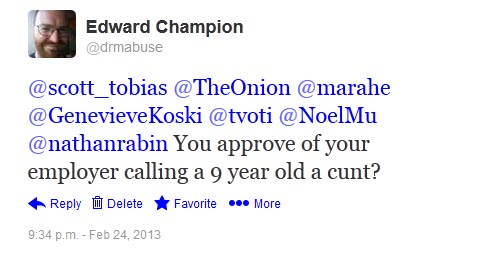

That evening, on Twitter, I sought vital answers. Why didn’t anybody at The Onion or The A.V. Club wish to be held accountable for the tweet’s underlying misogyny?

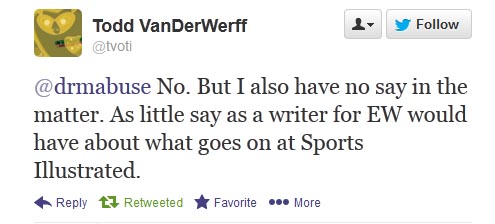

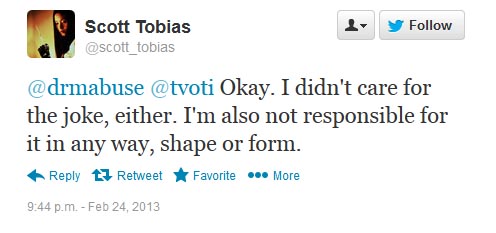

On Sunday night, I entered into a seventeen tweet volley with two editors at The A.V. Club: Scott Tobias and Todd VanDerWerff. VanDerWerff was fair, civil, and unimpeachable throughout the exchange. When the imbroglio hit a low point two days later, it was VanDerWerff who provided insight into The Onion‘s operational structure and tried to mediate in the comments. On Sunday night, as The Onion was being profusely lacerated, VanDerWerff would respond with calm, kindness, and grace to a woman who had raised concerns about the casual sexism on The A.V. Club‘s forums:

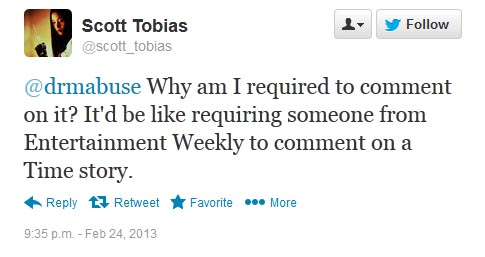

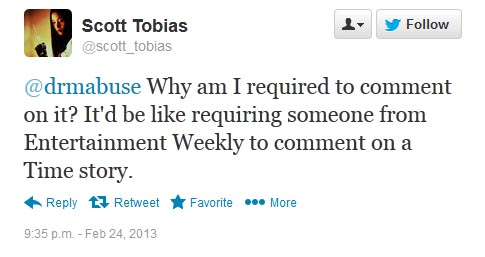

By contrast, Tobias was hostile to dialogue.

So I wrote an article about the Onion‘s tweet and the exchange I had with Tobias. The article was accompanied by a photo of Tobias, with the “cunt” tweet positioned across The A.V. Club‘s logo to his left.

I cop to the possibility that it may not have been a good idea to put the photo up. But in the early stages of the affair, nobody had deemed the photo especially noxious. Before The Onion apologized for the Wallis tweet on Monday morning, nobody had said a word in my article’s comments about the photo’s apparently offensive qualities. It was only after I issued an apology to The A.V. Club in the comments that Tobias showed up, decrying my “non-apology apology” and bringing up the photo issue on this website. In examining Scott Tobias’s Twitter timeline, we discover that just before The Onion‘s apology, Tobias’s concerns about the photo had nothing to do with the tweet’s juxtaposition:

The photo’s copyright did not belong to Scott Tobias. My subsequent investigation revealed that the photo belonged to The Onion, Inc. Tobias never had the right to assert copyright.

The photo did not libel or defame Mr. Tobias in any way. It depicted very clearly what I wrote about in the piece: a disembodied tweet lingering at a slight diagonal angle in The A.V. Club‘s environment as Scott Tobias stands with a reluctant grimace to the left. The photo did not sully Tobias’s image and likeness in any way. There was certainly no malice intended by this contextual abutment. It merely illustrated how misogyny exists in our culture, how it isn’t going away anytime soon, and how men often stand in place grimacing as the atavism continues.

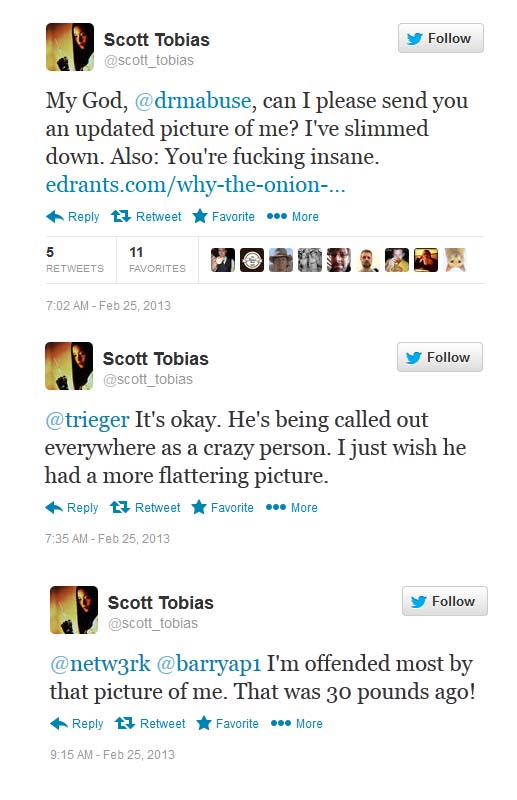

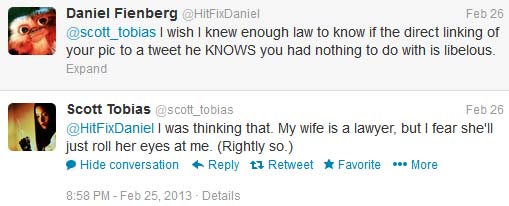

Tobias’s motivation to remove the photo shifted from vanity to a case of hypothetical libel, as suggested by HitFix‘s Daniel Fienberg:

It was clear that these guys didn’t know what they were talking about, but the suggestion of libel kept Tobias licking his lips. While all this was going on, I wasn’t even on Twitter.

* * *

I first became aware that something was going on when Tobias had left a comment on this website on Monday night. At the time, I was unaware of his public requests to remove the photo on Twitter.

When The Onion apologized on Monday morning, I thought that the matter was closed. I have said nothing further about The Onion, The A.V. Club, or Mr. Tobias on Twitter since that morning. (I would hold my silence as the nasty accusations, fallacious charges, contemptible threats, and scabrous suggestions, all instigated by Tobias, poured in over the next three days.)

I had stayed offline during most of Monday to get some work done. But I did briefly poke my head from the thickets of real life at 5:52 PM to offer an apology in the comments:

Since The Onion has stepped up to apologize for its tweet, I feel that I owe The A.V. Club a modest apology. While I still believe, as I specified in the piece, that The Onion and The A.V. Club should be beholden to some form of institutional values so that nastiness like this does not happen again, and while I feel that those who work for a publication should be intimately familiar with the way in which regrettable tweets set a tone, and while I feel that the seventeen tweets I offered over the course of 45 minutes (eclipsed by the scores of tweets from A.V. staffers over a period of seven hours throughout much of today, while I was busy working) do not constitute “mindless harassment,” I should have been more circumspect in contacting the people directly responsible for the Twitter feed.

In the interest of clarity, I should note that, even though I mentioned the “scores of tweets from A.V. staffers” in my comment, this was based on a cursory glance at Twitter on my phone in the afternoon, when I had tweeted a Richard Ben Cramer quote. I did not see tweets from Tobias calling for the photo to be removed.

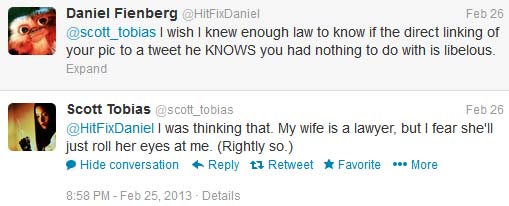

What I did not know was that Tobias, not pleased in being challenged, had initiated a plan to condemn me on Twitter and attempt to destroy my reputation. (The complete timeline of events is presented in this detailed graphic.)

On Monday afternoon, at 1:36 PM EST, Tobias tweeted a public request for me to remove the photo. I did not see it. There was no Twitter notification by email. At 10:27 PM EST, Tobias tweeted a second public request. I did not see it. There was no Twitter notification by email.

Tobias had not emailed me.

At 10:25 PM EST, Tobias left a comment on this website, which I approved and read shortly thereafter. I replied at 10:57 PM EST, asking Tobias to address his concerns through formal correspondence.

Curious about what Tobias was referring to, I went to Tobias’s Twitter feed and learned that Tobias accused me of being “vile,” called me “fucking insane,” and had suggested to his followers that I had deliberately rebuffed him.

Again, I had not seen his tweets before then.

I am normally quite happy to remove photos when people ask. I have done so in the past. But Tobias’s harassing behavior is not how you go about getting a photo removed. And when I went to the trouble of getting the notice necessary to remove the photo, something that was not my obligation, the process took two days.

I was unclear about the copyright being asserted and I wanted to be absolutely pellucid on the facts. This was because I had not been entirely circumspect about The Onion‘s organizational structure with my initial article. For this, I was pilloried by Tobias’s peers as “a terrible asshole,” “a cunt,” “a real cunt,” “a fucking cunt,” “a world-class creep,” “an awful troll,” and numerous other epithets that flowed late into the night. I was condemned for being slow and methodical. I had not received a takedown notice.

I contacted people at The Onion on Wednesday and Thursday morning (including CEO Steve Hannah, TV editor Todd VanDerWerff, and HR Coordinator/Office Manager Theresa Lyon), apprising them of the full situation and instructing them that I would need something specifying (a) copyright information on the photo, (b) contact information for the aggrieved party, and (c) a statement asserting in very clear language why the material is not authorized, and also requesting a public apology. (In fact, I have yet to receive any apology, either private or public, from Scott Tobias or anyone at The Onion or The A.V. Club.)

It was never my job to educate Tobias about copyright law. There is a formal process to remove a photo. But despite working in the media business for at least fourteen years and being married to a lawyer, Tobias did not follow the procedure. As the detailed timeline demonstrates below, he was more interested in devoting his energies to harassment. (If you can’t see the image in full, right click on the image in your browser and select “View Image” and click again to zoom in.)

The collective outrage was never about the photo. It was about power. In the 1980s, Heinz Leymann investigated mobbing, a collective form of harassment in the workplace which he defined as “hostile and unethical communication which is directed in a systematic way by one of a number of persons mainly toward one individual.” As cafes have increasingly transformed into offices, Twitter has created a new virtual “workplace” atmosphere.

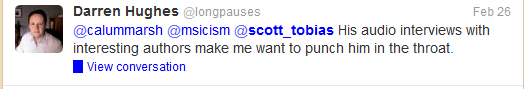

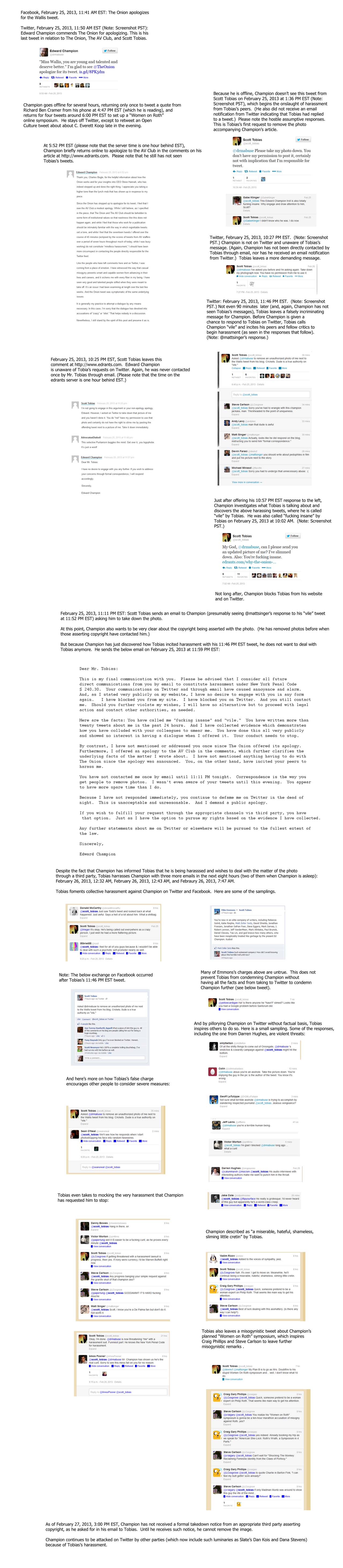

When I learned what Tobias was up to on Monday evening, I informed him by email that he was harassing me and that I only wanted to deal with third parties. He continued to harass me and it caused people such as Darren Hughes to make violent threats:

Tobias’s tweets inspired a few hundred additional tweets from his peers which hurled more invective along these lines. As the timeline graphic clearly demonstrates, not once did Tobias seek to mollify his followers. He was the ringleader in a campaign built on collective harassment. It’s the kind of behavior one associates with 4chan, not purportedly high-minded cultural critics or people who work for The Onion and NPR.

Tobias’s tweets also inspired an effort by Slate staffers to suggest that I was a troll. It was precisely the linguistic switcheroo that Richard Cooper had identified in his essay on Twitter hierarchies:

The hideous term “trolls”, previously reserved for the kind of racist or neo-Nazi filth people put in YouTube comments sections to get a reaction, was now being used to apply to the phrases “yawn” and “one step up from a mumsnet post”.

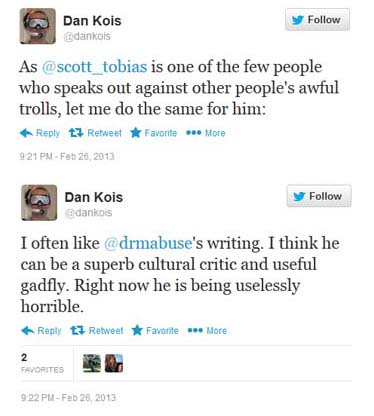

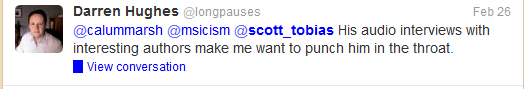

From Dan Kois, Slate senior editor:

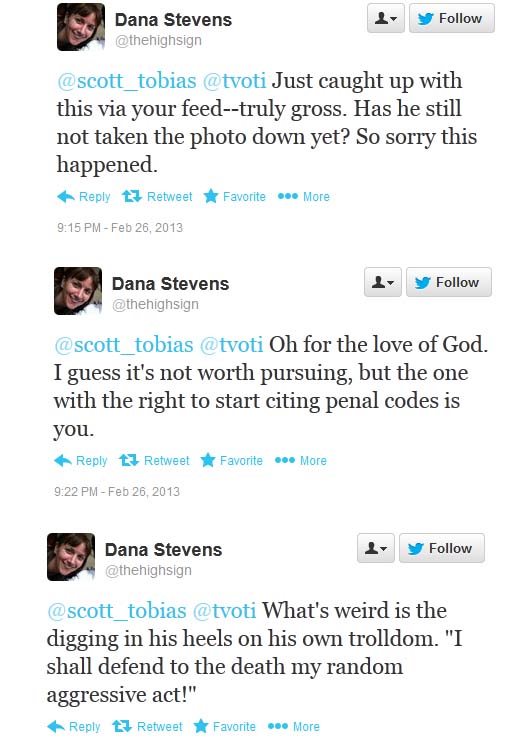

From Dana Stevens, Slate film critic:

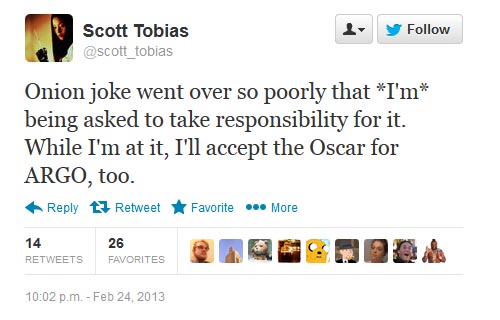

The irony of cultural critics smearing a critic of a critic has not been lost on me, nor has the irony of male critics who who are more offended by a mild photographic juxtaposition than a misogynistic tweet directed at a nine-year-old girl. This upholds the very point that my piece and the accompanying photo argued: that institutional values within today’s cultural outlets prohibit an examination of casual misogyny. With professionals like this, who needs critics?

* * *

It was amazing to me how Twitter had inspired the 21st century’s answer to The Ox-Bow Incident. I was never contacted or afforded a perspective. There was one creepy “assistant professor” who was spending his time between classes harassing me and stopped doing this after I called his program coordinator. The narrative that Tobias created left zero room for painting me as anything less than a baleful menace. All I had done was put up a photo and raise my voice. I never insulted anybody during the Sunday night exchange. I certainly hadn’t killed anybody or defended phone hacking. The reaction was tremendously out of proportion with the purported offense.

Scott Tobias had turned the film critic community on Twitter into a thoughtless mob.

In the end, I decided to remove the photo: not because of the harassment and not because I was pressured. Even though Tobias had harassed me and publicly crucified me before I had ever had the chance to respond to his requests, decency and compassion were essential parts of journalism. He had not been especially decent or compassionate to me, but I wanted to believe that there was a decent human being somewhere inside Scott Tobias. I wanted to be kind when the others were being quite unkind.

I took steps to get The Onion to send me a formal takedown notice and eventually heard back from A.V. Club general manager Josh Modell.

With the official takedown notice in my hands, I quietly removed the photo.

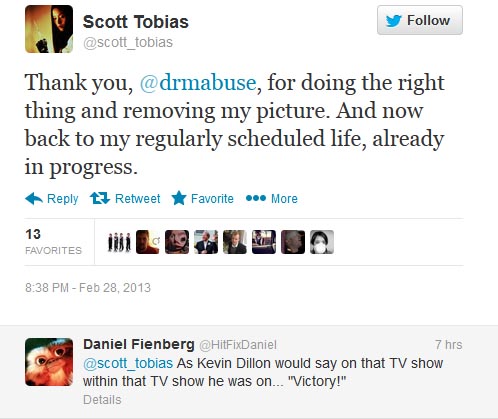

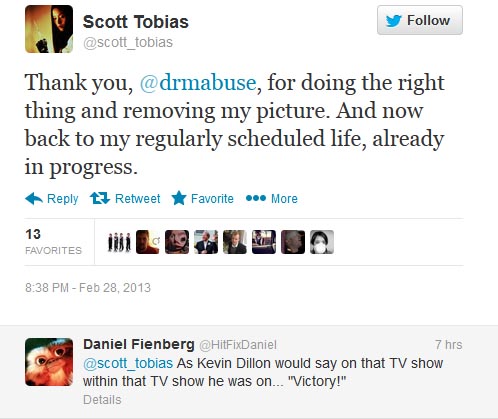

Within twenty minutes of the photo’s removal, Scott Tobias acknowledged this on Twitter. But he did not apologize for his conduct or for riling up his peers. Indeed, the tone here was rooted around celebration and “victory” rather than dialogue and decency. In Tobias’s mind, he had “won.” I don’t know if he has learned anything.

You can’t tar people because they haven’t responded to your timetable. I fully admit to being guilty of this in the past. Now that I’ve seen it from the other side through Tobias, I better understand why patience is essential. Without patience, we dehumanize ourselves by viewing other people as blank lemmings who fall into a natural pecking order.

I don’t know if the film critics who harassed me on Twitter are even cognizant of what they’ve done. Did Twitter turn them into monsters? I’ve certainly tweeted my share of foolish and angry sentiments, but it has never occurred to me to incite my friends to harass anyone writing something critical abiout me. As Nagasawa put it so well in Murakami’s Norwegian Wood, “A gentleman is someone who does not what he wants to do, but what he should do.” (To which Watanabe replies, “You’re the weirdest guy I’ve ever met.” To which Nagasawa replies, “You’re the straightest guy I’ve ever met,” just before paying the bill.)

The high road doesn’t get enough credit in American life. It takes a hell of a lot of courage not to respond to beasts who want to bring you down. They are so eager to destroy and shame that they lose their sense of humanity. Yes, we all make mistakes. And we can’t expect people to react in the way we want them to. But isn’t it better to behave like a gentleman?

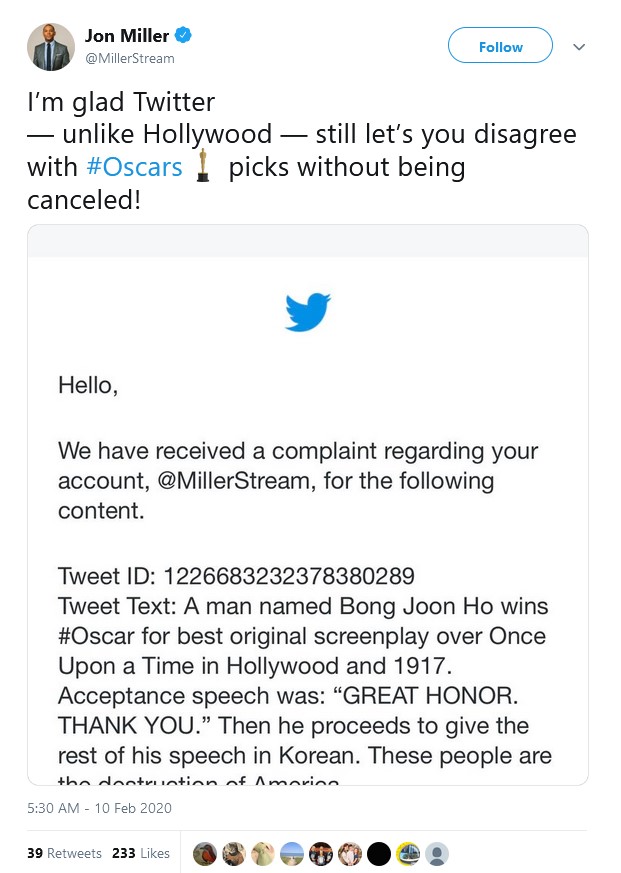

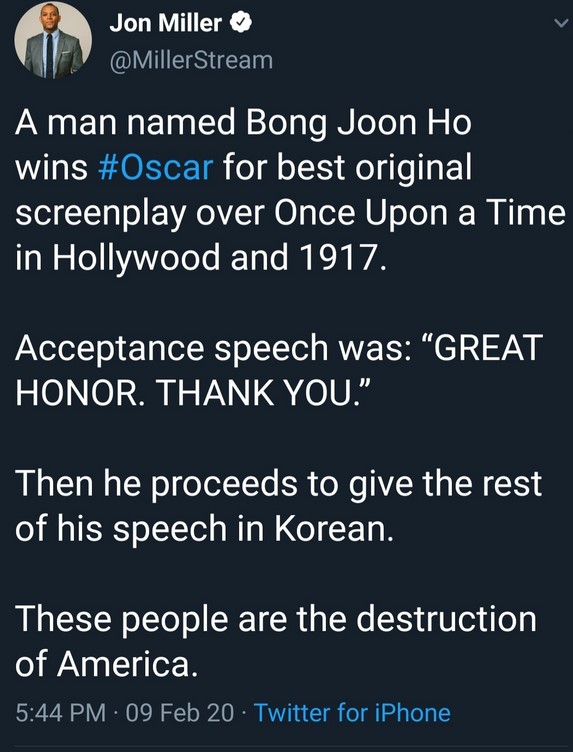

A man with a blue checkmark by the name of Jon Miller, a conservative “White House correspondent for BlazeTV,” tweeted an insulting, cruelly disparaging, and racist message mocking the great filmmaker Bong Joon-ho after he delivered one of his Oscar speeches in Korean. Miller’s disturbingly xenophobic words, which are still published on Twitter as of Monday morning, proceeded to claim that “these people are the destruction of America.” This is language that echoes anti-Semitism in 1930s Germany and

A man with a blue checkmark by the name of Jon Miller, a conservative “White House correspondent for BlazeTV,” tweeted an insulting, cruelly disparaging, and racist message mocking the great filmmaker Bong Joon-ho after he delivered one of his Oscar speeches in Korean. Miller’s disturbingly xenophobic words, which are still published on Twitter as of Monday morning, proceeded to claim that “these people are the destruction of America.” This is language that echoes anti-Semitism in 1930s Germany and