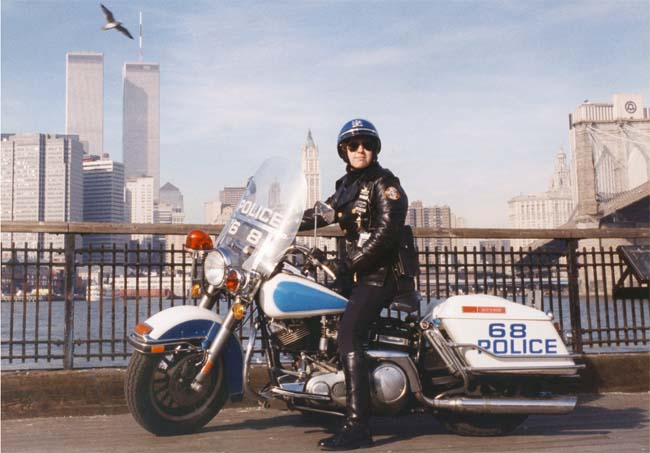

In 1953, the idea of a single female police recruit to the New York City Police Department, let alone a handful, was big news. And when the New York Times wrote up the-then shocking idea of these women engaged in public outdoor physical activity as part of the examinations they needed to pass, naturally they included photos of the department’s newest members — including one young mother and engineer’s wife, born and raised on Ryer Avenue in the Bronx. A decade later, Dorothy Uhnak immortalized her beat-walking experiences — which included knocking down a robber more than twice her size — in her memoir Police Woman.

By the end of the 1960s, Uhnak had added to pioneering police work literary acclaim with a trio of award- winning novels following the career of Christie Opara, a detective protagonist as cool and methodical on the trail of multiple murderers (The Bait) political protesters (The Witness) and mobbed-up types (The Ledger) as she was raising a child on her own and considering a romance with her brash and sharp-tongued boss. Consciously or otherwise, Uhnak was planting the seeds for female detectives more private-minded — like Millhone, McCone and Warshawski — and subsequent generations of hard-boiled literary women. But until the Times reported Uhnak’s death of a self-administered drug overdose in 2006, her contributions went unnoticed by a great many readers — including me. I soon realized this void was shameful on several levels.

Uhnak dispensed with Christie Opara so quickly (a much-altered version of the character surfaced briefly on television in Get Christie Love) because her matter-of-fact prose and complex characters needed more room to breathe. Spurred by her editor’s desire to emulate such 1970s publishing phenomena as Mario Puzo’s The Godfather and Joseph Wambaugh’s The New Centurions, Uhnak made the leap from tight-focus cop chronicles to blockbuster sagas, including 1977’s The Investigation and Victims (1985), a loose account of the Kitty Genovese murder. Sadly, the only one of these novels that remains in print is the first, the meaty, multi-generational doorstopper Law and Order (1973), which charts the entwined fates of the O’Malley family and their perpetual employer, the NYPD.

Those twin worlds, depicted between 1937 and 1970, are insular ones. The O’Malleys, with their repeating names and vigorous breeding habits, are too busy taking care of their own — personally and professionally –to bother with what happens outside their Ryer Avenue environs or the codes, written or otherwise, of the department. A brutal opening scene sketches the boundaries of the mindset. When the elder Brian O’Malley, a hard-drinking, rough-living Irish cop, meets his grisly death at the hands of a black prostitute he frequents, “I don’t want any part of it,” thinks his brand-new partner, Aaron Levine. “God he wished they were on their way back to the precinct house. It was nearly time for the tour to end. He never thought that filthy precinct would feel like home, but it was where he wanted to be right now.”

Levine’s wilful blindness, which continues as he slides all the way up to a cushy academic position (the reward for his “not wanting any part of it”) is the key metaphor for how people operate in Law & Order. O’Malley’s death is covered up, blamed on a robbery gone wrong. His eponymous son Brian steps in his father’s place, a brilliant recruit on the fast track to becoming Detective Chief Inspector — but not before he also tunes out the disturbing signals that don’t fit the overall narrative of cop culture. As for the O’Malleys as a family, they too doom themselves to repeating the same mistakes, generation after generation. Margaret, wife of the original Brian, grows from a young woman fearful of the clan she’s married into a hardened shell prone to snapping at her children. Eldest daughter Roseanne pays the price of her insolent adolescence when the wild young man she fancies turns out to be a rotten husband (her niece Maureen, the daughter of Brian Jr., will make virtually the same mistakes decades later.) Brian is himself prone to self-castigation about “sins of the flesh”, going so far as to try purging himself at the confessional, but — even after marrying a girl whose supposed job it is to rid himself of base desires — he indulges in multiple affairs.

The sense of fait accompli comes out even in how Uhnak depicts Brian Jr.’s original police examination: “Thirty-three thousand young men took the examination for Patrolman, New York City Police Department. Fewer than twelve hundred survived the written, physical, medical and background check-out. The class at the Police Academy was comprised of the top 10 per cent of the resulting list of eligibles. Eighty-five per cent of them held college degrees. By the time they received their appointments, they all knew they were something special.”

No wonder then such recruits, like Brian, are invited to do as they please; to free, for example, a statutory rapist of a neighborhood girl considered to be a slut — while another man, guilty of raping Brian’s young sister, merits a life-threatening assault. No wonder certain recruits are allowed to take a doctored exam while others cavalierly murder in the name of shutting up a would-be snitch determined to expose department-wide corruption. It’s only when the stage is set for Brian’s son Patrick, fresh off a tour in Vietnam that’s exposed him as much to war as it has to racial divides, to take his place in the cop pantheon, that the presumptions undergirding the system are threatened.

Which is why, when the bad apples have been shaken loose and events mimicking the 1972 Knapp Commission partially reveal the fault line of corruption – as well as the truth about what happened to Brian, Sr. — we’re left with Patrick, having a drink with his old man, his mouth open and holding his hands up. “Christ, isn’t there a moral way to commit a moral act?” asks the younger O’Malley, sick with disillusionment over how the Department handles corruption from within. His father has none of it. “In all of my life I’ve found morality counts shit when it comes to getting a job done. What counts is doing it any goddamn way you can, but get the job done.”

When their minds meet, resolved in a middle ground, Law & Order completes its newest generational cycle, where innocence crumbles in the face of hard-earned cynicism and means justified by the ends. The NYPD is as much family as the O’Malleys, and in Uhnak’s hard-bitten world, both of them — no matter the cost — take care of their own.