For a large chunk of Tuesday, just as the dust started to settle upon the tail of a particularly dystopian year, I kicked Jonathan V. Last in the balls. Repeatedly. Regrettably, this low-hanging flagellation (and Last’s responsive groans of pain) was confined strictly to my imagination. However, I found that the more that I fantasized about my steel-toe Doc Martens colliding into the scrotal region of one of America’s foremost political grifters, the more it became possible in the real world. Perhaps it had already happened? The thought had given me hope. A New Hope, as it were. (Stay tuned!)

If you consider this to be a strange pastime, well, it’s not altogether different from the remarkably predictable way that Jonathan V. Last has devised his half-baked and covertly fascist theses over the course of his checkered career (a small sample of Last’s pablum to neutralize any potential “Trust me, bro!” allegations leveled at yours truly: Maybe it’s just too much effort to protect immigrants from ICE! Mike Pence is a hero! Let Trump be Trump!). Except that my idea was more violent and thus decidedly more entertaining.

Before this remarkably vapid and autocracy-friendly douchebag fell upward to become editor-at-large at The Bulwark, Last was known for defending the Galactic Empire in Star Wars — quite literally the only self-identifying geek who has ever defended one of the most tyrannical fictitious institutions in cinematic history. I can legitimately imagine George Lucas reading Last’s piece and saying, “How did this ghettoass motherfucker come up with that takeaway?” But let us adopt a more pragmatic tenet from the Spielberg-Lucas oeuvre, shall we? It stands to reason that if it was okay for Indiana Jones to punch a Nazi, then the modern day parallel would involve kicking Nazi-friendly transphobic fuckheads like Jonathan V. Last repeatedly in the balls. He is, after all, a not very perspicacious scumbag who now spends many of his spare moments stroking his salami to Marjorie Taylor Greene. And, look, I don’t want to kink shame. But when an extremely stupid person’s kink begins to dwarf his understanding of basic democratic principles, there comes a time for violent fantasies and longass vitriolic essays to be directed against the dunderhead in question.

Let us state the truth plainly:

Jonathan V. Last is more equipped to pump gas during a particularly harsh New Jersey winter than write a regular political column.

Back to Mr. Last’s gonads.

Earlier this week, the general region down there, which was quite chapped and inflamed because of Last’s penchant for onanism (both as a sad sack conservative writer and as a sad sack human being), needed a little more variety (and perhaps a little more lube). Last’s hands had been down there far too frequently when writing his “thought pieces.” And if he was going to abuse himself (and damage his junk) in the privacy of his own home, why not replace the incessant and overly rigorous stroking with sharp painful kicks? Perhaps Last’s painful yelps in response to this well-earned testicular violence could be recorded with a quality Neumann microphone and become a new Wilhelm scream for the 21st century or, failing that, walla for some forthcoming episode of Pluribus. Last also required apposite payback for risibly claiming that MTG — one of America’s foremost fascists, a believer in Jewish space lasers, a 9/11 truther, a monster who suggested that Nancy Pelosi be executed for treason, a racist who had called whites “the most mistreated group” in America, an evil and illiterate grifter who knowingly denied that Biden had won the 2020 election and who was involved with the January 6th insurrection — was a champion of what Last called “liberal democracy.”

I kid you not. This is the remarkably gormless and highly gullible mouthbreather steering a sizable chunk of the “liberal” ship The Bulwark. He has, rather amazingly, not been given a banker’s box for his office possessions and a thorough ass-beating by a security guard. And the fool still holds onto his job. And on BlueSky, Last tried to have the last word by delivering this whopper:

Yes! By all means, give MTG a cookie for adopting such “policy preferences” (a phrase that sounds as ridiculously harmless as a health-conscious diner seeking the gluten-free options on a labyrinthine menu) as deliberatly misgendering a colleague’s daughter, banning the display of Pride flags, opposing the Equality Act, warning everyone about the Gazpacho Police (an apparent existential threat to all hot soup in America!), calling all Democrats “pedophiles,” calling anyone aiding the FBI “a traitor,” and many other gaffes and perversions of “liberal democracy” as we have known it in America for more than two centuries!

Of course, there have been many other reasons to kick Jonathan V. Last in the balls — repeatedly and with great accuracy so he can at long last understand that every opinion piece he has ever published is indistinguishable from five tons of shit burning in a dumpster. There’s the endorsement from imperious tadpole Chris Cilliza as “my favorite thinker and writer operating in the political space right now.” There’s Last’s superficial description of Trump’s dangerous policies as “a whole bunch of bad stuff that is coming,” which reads like something that the Pakleds on Star Trek might have written if they were hired as political pundits. There’s Last’s insufferable cleaving to the “JVL” moniker, as if he is some VIP regular at a five-star hotel or this acronym alone somehow absolves him of his limitless stupidity. The only rival to Last’s lock-in as a guy you want to repeatedly kick in the balls is probably Ezra Klein — another political “thinker” deserving of scabrous opprobrium whom I’ll have to take to the wood shed some other time.

As I imagined Last’s cadaverous lips careening upwards in agony as he keeled over with each and every cold swift kick to his balls, I began to wonder if kicking Last in the balls would be enough to get him to understand how useless his opinions were to the human race. I begin to wonder if I should keep a bottle of bubbly in the fridge in the event that Jonathan V. Last was stabbed. I began to adopt the position that inflicting pain upon a paleoconservative asshole like Jonathan V. Last, whether real or imaginary, represented the most common sense remedy against the present national epidemic of dumbass writers punching above their weight.

I was free to imagine and memorialize all of these condign responses because, unlike other writers, I have no interest in writing for The Bulwark and, as such, possess an ethical core that circumvents the possibility of being seduced by the devil. You see, that’s how a dope as unfathomably idiotic as Last has risen to the top. If you inure yourself to much-needed pushback from other writers by becoming someone who could theoretically assign another writer a freelancing piece, then your words, however stupid, will be taken as gospel by a certain trough-eating crowd. I mean, even the enjoyably ferocious writer Moira Donegan pulled her punches when Last was being rightfully dogpiled on BlueSky.

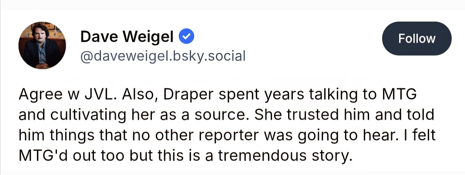

If I can offer one invaluable idea that we can carry into the new year — a year with very important midterm elections that will determine whether or not we still have a legitimate democracy — it’s this. Kick the grifters in the balls. Whether literally or with your imagination. People like Last have been allowed to bang out horseshit for years without consequences. Last has no real strategies, much less any real understanding of historical patterns or vital precedents. He is a parvenu and a grifter, a guy who should be 86ed from any bar with at least four regulars who are journos. He betrays the purpose of journalism with every piss-poor sentence he bangs out like some spastic monkey who just started a new antidepressant prescription. Kick the motherfucker in the balls. Starve him of oxygen. Block him. Do not link him. And pay attention to other grifters like Dave Wiegel, who — sure enough — stood up for Last in the manner of a sweaty and closeted linebacker snapping a tight end with a locker room towel right after the big game:

Access journalism has always been a line that I will never cross. I’ve done hundreds of interviews in my life and I’ve never agreed to prerigged questions. Normalizing fascists — in this case, following The New York Times’ greasy lead, is similarly a point on which I will never bend. (And I’ve turned down serious dinero that fuckheads like Last and Wiegel will lap up like demented six-year-olds scarfing candy down their corpulent gullets.) For Last and Wiegel, the betrayal of basic Fourth Estate principles represents a thrill that is as seminal as Laura Loomer dreaming about giving That Orange Sack of Shit a handjob under his desk as he is on the phone taking orders from Putin.

They are both enemies of the American people and enemies to journalism. And they both need to be kicked in the balls until they can summon a take that doesn’t answer the question “Do you spit or swallow?” If we want our nation to return to some semblance of how it was before Evil Motherfucking Trump, we have scrotums to kick and vital standards to uphold.