Maud points to this New York Times item on Gawker. David Carr criticizes blogs (and specifically Gawker) for being “remarkably puerile to make jokes…[when Fairchild Publication] has posted guards in the company’s office because [Peter Braunstein] is suspected of drawing a target on people working there.” Gawker editor Jessica Coen may revel in bad taste (certainly Coen’s ridiculous identification of Laila as a “Muslim-by-way-of-Portland blogger” has been deservedly taken to task by several parties). But who is to suggest that Gawker, as tasteless as it might read at times, should be criticized solely because Carr finds it offensive? Is it possible, perhaps, that in finding gallows humor in the verboeten (even through Gawker’s decidedly tawdry timbre), Coen may very well be discovering another mode to express “the vocabulary for genuine human misfortune?” Or maybe she’s alerting six million readers that yes, Virginia, contrary to the safe ‘n’ sane overlords who hold the keys to the castle where none are offended, tea is served at noon and the happy little elves dance a harmless waltz, you can indeed find a guffaw in the forbidden.

I haven’t been all that much of a Gawker fan since the halcyon days of Spiers and Sicha. But it’s truly unsurprising that we have another telltale sign here from an outlet which, on a daily basis, fails to stand by its dubious credo “all the news that’s fit to print” because they fear offending subscribers. One indeed that has suffered credibility problems of its own and that would publicly denounce anyone daring to push beyond the threshold into issues unseen and unexamined. First off, there’s the possibility that the image-obsessed world of the Condé Nasties or the sordid and duplicitous subculture of gossip journalism may have had a hand in pushing this sociopathic personality over the edge. Further, why was such a man employed, even after he exhibited stalking tendencies? Surely, any company who regularly sends reporters into the field would not want to face a costly harassment lawsuit from one of its employees.

That’s interesting from a human behavior standpoint and, as far as I’m concerned, ripe for comedy. Or as Mel Brooks once put it, “Tragedy is when I cut my finger. Comedy is when you walk into an open sewer and die.”

Coen’s tossed off posts may be unfunny, but only because they are poorly phrased or lack a specific association. This is not to suggest the topic of rape, as hideous and as awful as the subject matter is, is entirely devoid of comic value. Mostly unfunny, sure. But did we learn nothing from Lina Wurtmuller’s ingenious cinematic satires of the 1970s or, more recently, Catherine Breillat’s films or Pedro Almodovar’s Kika, which have employed rape sequences to make audaciously satirical statements about how women are regularly subjected and humiliated? The Lenny Bruces, the Richard Pryors, the Lina Wurtmullers, the Onions and the Terry Southerns of our world all understood that comedy designed for audiences who are easily offended by studs which mismatch a country squire’s cufflinks is never revolutionary and, for the most part, quite dull.

One of the reasons blogs have thrived is because they combat stiffs like Carr, columnists who exist on the Gray Lady’s payroll solely to bang out 1,000 words pointing out the bleeding obvious. Blogs dare to employ tones and write about taboo subjects that elude a profit-driven newspaper. They eschew the American newspaper’s prudish tone and have no full-page advertisers to answer to. In the best of cases, they combine wit, irreverence and an original idea. Perhaps the six million people are drawn to Gawker because they want to see what Coen will come up with next. Or perhaps they wish to take a trip down a dark road to discover the sordid alleys that mainstream outlets fear to tread.

Sure, it may be “more adult” to look the other way, avoiding some of the more deranged realities of our world, whether through disgust or willful ignorance. But such an approach also means siding with the newspaper-reading Babbitts of the world, those who would remain unchallenged and trapped within the obligations of crippling mortgages they must meet, children they must raise, and bosses they dare not cross. Humorless miens indeed.

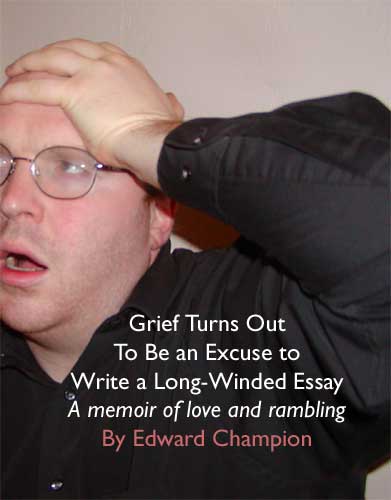

“And then — blogged.” In the midst of life we are surrounded by obsessions, and I had said this sentence one too many times. It had not been said by any philosopher of note. Later I realized that my rage at the newspapers, compounded by their deafness to my creative pitches, is what led me to become some febrile chronicler of literary motifs and happenings. Friends were kind enough to not tell me directly that I was chasing windmills, letting me find out for myself that such a regular plan was far from tenable. Never once did I exploit the intimate details of my personal life. All this without that bradykinetic yet pivotal period of thinking, of allowing dreams to unfold and wild ideas to transform into arguments and complex tales.

“And then — blogged.” In the midst of life we are surrounded by obsessions, and I had said this sentence one too many times. It had not been said by any philosopher of note. Later I realized that my rage at the newspapers, compounded by their deafness to my creative pitches, is what led me to become some febrile chronicler of literary motifs and happenings. Friends were kind enough to not tell me directly that I was chasing windmills, letting me find out for myself that such a regular plan was far from tenable. Never once did I exploit the intimate details of my personal life. All this without that bradykinetic yet pivotal period of thinking, of allowing dreams to unfold and wild ideas to transform into arguments and complex tales.  I used to have a large white dry erase board in my small rented room, for reasons having to do with a silly effort at appearing professional. Initially, I drew task lists for what I needed to do during any given week. But because the markers were colorful, I soon began drawing obscene pictures involving stick figures in flagrante delicto. I would invite friends to come by to play drunken games of Pictionary, carefully rationing the large bottle of Jim Beam that I had purchased on sale at a Safeway earlier in the year. I was using the dry erase board as a way to keep things going in light of the grief that threatened to destroy my routine.

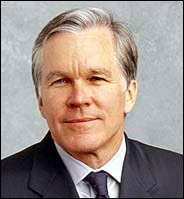

I used to have a large white dry erase board in my small rented room, for reasons having to do with a silly effort at appearing professional. Initially, I drew task lists for what I needed to do during any given week. But because the markers were colorful, I soon began drawing obscene pictures involving stick figures in flagrante delicto. I would invite friends to come by to play drunken games of Pictionary, carefully rationing the large bottle of Jim Beam that I had purchased on sale at a Safeway earlier in the year. I was using the dry erase board as a way to keep things going in light of the grief that threatened to destroy my routine.  In a letter, New York Times Executive Editor Bill Keller

In a letter, New York Times Executive Editor Bill Keller