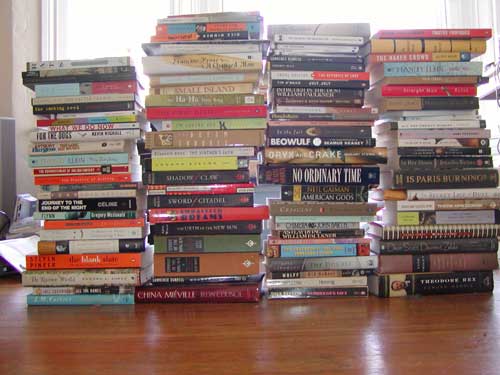

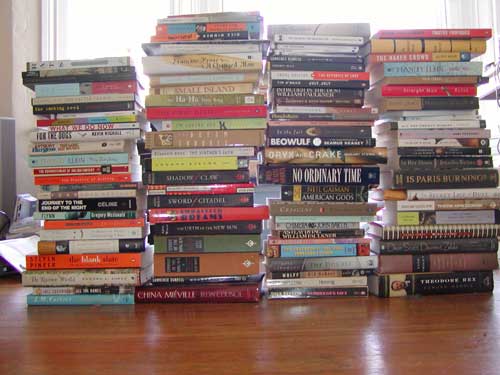

Since some of you asked… (Note: Some of these are rereads.)

Okay, I’m officially out of here.

Since some of you asked… (Note: Some of these are rereads.)

Okay, I’m officially out of here.

Rick Gekoski’s idea of bliss involves reading a book a day. He’s a Man Booker judge for 2005. And with 130 titles to read in five or six months, the real question here is how much is too much. And is Gekoski the intelligensia’s answer to Harriet Klausner? (via Bookninja)

Ulrich Baer has written to the Rake with a lengthy essay about the creation of his book, The Wisdom of Rilke: “My process of translation involves a lot of reading out loud, mumbling, and general behavior unfit for a public space. I read the German or French sentence a few times, try to allow its meaning, speed, and rhythm resonate within me, and then try it out in English. All the while I am more or less speaking to myself, listening for an approximation of the particular movement of Rilke’s thought and phrasing in English.”

Last night, at Chateau Mabuse, the power went off. We were sorry to see our pages on the computer lost into the ether. But this did, nevertheless, lead us to the romantic notion of reading by candlelight for several hours.

It proved more problematic than we expected. But since we had a few unexpected hours on our hands, we took the time to experiment and iron out the kinks. Here’s a checklist to help others plan for successful reading during a blackout:

Malcolm Gladwell‘s Blink isn’t as satisfying as The Tipping Point — in part, because Gladwell’s tendency to generalize is more prominent this time around. (Case in point: We’re supposed to marvel over John Gottman’s ability to determine if a married couple will still be together in fifteen years. Gottman can assess this with a 90% accuracy. Never mind that half of all divorces occur within the first seven years of marriage and that, depending upon what authority you consult, it is generally agreed that roughly half of all marriages end in divorce. An existing 50% probability weighed in with Gottman’s concentration on couples in their twenties — that is, divorces more inclined to occur, because younger people are more likely to divorce — and Gottman’s educated guesses leave a lot of wiggle room for the remaining 40%.)

Nevertheless, Gladwell’s interests in sociological and marketing casuism are always food for thought, particularly since he’s keen to serve up fascinating anecdotal examples. While he barely scratches the surface of “thin slicing” — the term Gladwell coins to describe what happens when someone uses latent subconscious impulses to serve up a quick judgment — he has got me thinking about how much of the publishing world is fixated on immediate judgment.

Terry Southern once remarked that, when he worked for Esquire, he could judge the quality of a manuscript based off of the first sentence. I’m wondering whether certain types of fiction are doomed because of the thin slicing editors have been applying to the slush pile. Was Richard Yates never published in the New Yorker because the editors trained themselves to react distastefully to Chekhovian naturalism? (Magical realism and postmodernism was very much the order of the day when Yates submitted his wares.) And just how much of this mentality is in place today?

(And I should point out that we’re all guilty of this. I don’t wish to inure myself. Recently, while reading its early pages, I was ready to damn Tricia Sullivan’s Maul based on what I perceived as tedious cross-cutting between the game going on in Meniscus’s mind and the cramped confines of a lab, until I gradually became aware of the subtle cultural allegory. Had I not kept reading after 100 pages, I would have probably have dismissed what turned out to be a daringly rugged novel.)

Further, if thin slicing is endemic to the book world, is this mentality what causes once popular authors like John P. Marquand (who made the covers of Time and Newsweek in 1949) to go out of print?

In one chapter, Gladwell uses the musician Kenna as an example for why certain forms of thin slicing aren’t always the best indicators. Kenna, who had earned nothing less than contagious kudos from such luminaries as Fred Durst and U2 manager Paul McGuinness (who flew him over to Ireland), along with repeated MTV2 airplay, built up such a sizable buzz that he packed a sizable crowd into the Roxy in less than 24 hours’ notice. But Gladwell notes that when Music Research did marketing, Kenna scored miserably and was thus unable to secure Top 40 radio airplay.

Gladwell suggests that Kenna’s failure with the number crunchers was because only certain forms of thin slicing works. Kenna’s music was not easily classifiable. Gladwell implies that some opinions are best formed over time and that corporations who are introducing products that are slightly foreign (such as the Aeron chair, another example that Gladwell uses) need time to be accepted (which may explain the repeated rejections that Sam Lipsyte’s Home Land received before becoming a cause celebre).

Since fiction is a form that often requires a careful reader to weigh in a story, it would be curious to know just how much of it is getting short shrift from today’s editors. The number of careless typos that one finds in today’s novels (that indeed manage to make it all the way to the paperback release) is often extraordinary, signaling a growing lack of regard for how a book is typeset and put together. But it may be even more alarming to consider how many of today’s experimentalists (say, the David Marksons or Gilbert Sorrentinos of our world) are more the victim of overtaxed thin slicers whose waning passions for the written word waltz hand-in-hand with the first impression gone horribly amiss.

It’s not enough for Andrea Levy to win the Orange and the Whitbread. She’s just been nominated for a third award: the Romantic Novel of the Year Award.

Normally, we wouldn’t have any problems with this. We’ve long been awaiting Small Island‘s inevitable paperback version of a long-haired hunk mounting some bodice-ripped brunette against a conflagrating background — if only to have the hopeless Harlequin crowd accidentally reading a moving tale of two couples on an island.

The chief problem here is that the prize is sponsored by FosterGrant Reading Glasses. And while our librarian fetish is well documented, we have to point out that FosterGrant frames aren’t exactly daring or, for that matter, romantic.

And they damn well should be.

One would think that after centuries of eyewear technology, FosterGrant would have stumbled upon the ultimate solution — frames that provide practical vision for the far-sighted while considering the requirements of lascivious literary types.

Expansion of eyewear translates into expanding ideas of romance. And for far-sighted novelists, we’re talking a sharp dropoff in “slither slither” Wolfe-style bad sex and a veritable rise in “romantic novels.” So what of it, FosterGrant? Where are the reading glasses I can wear for the dominatrix? If we can’t be indecent on television, then we can surely be naughty in literature.

South Florida Sun-Sentinel: “Gov. Jeb Bush wants to increase spending on reading by $43 million this year and make reading money a permanent part of Florida’s public school budget.”

Hey, Jeb, give $43 million to me and I’ll give you all the reading you need. And then some.

I don’t know what bothers me more: the notion that $43 million given to “reading” without a specific spending plan sounds more like the cocaine tab hidden within blockbuster movie budgets under the heading “accessories” or the idea that money would somehow translate into a new generation of enthused readers through a osmosis involving dinero.

But then these are the kind of silly impressions one forms when an article fails to point at the specifics, which can be found here. And if you read the fine print, it isn’t about the reading at all, but the scores. No wonder some kids aren’t so crazy about books.

Sarah’s put up a thoughtful post regarding hearing voices when she reads. I can relate to this because, although my own inner ear parses text differently, I sympathize with the notion of those voices inside the book that tell me to do things.

Whole chapters of Ian McEwan, Alex Garland and David Peace have encouraged me to wash my hands more. Because when I’m reading a farrago of brisk one-to-two word sentences (“Fuck,” “Noon,” “My arse.”), I feel as if I’m channeling the spirit of Howard Hughes. If I’m, say, reading part of the Red Riding Quartet, chances are you’ll find me in the restroom, washing all of those evil smelly life-destroying molecules that CLUTTER one’s existence and otherwise INTERFERE with the precious bodily fluids have you ever seen a Russian drink anything other than vodka? that do me end and PREVENT me from living greatness, must keep the people happy and prevent the germs from spreading UP UP & AWAY flowing through my veins and arteries like some infernal beast, parasites that can only be seen under a microscope…

But I digress.

Conversely, when I am reading a paragraph-long sentence (a la badly translated Dostoevsky or W.G. Sebald), I suddenly find myself talking too much during a conversation. These austere paragraph-slingers wish me to expatiate and I must honor their wishes, for I too have something dreadfully important to say, so important that it must be framed within the context of a sentence with endless verbs, commas and wends that convey the Sense of Importance. Never mind that the people who listen are trapped there, wishing to be polite, hoping that the blathering fool who is recycling some heavy-handed Marxian metaphor will stop.

So, yeah, the short answer is that I hear voices too. And while I come from a family that is very musical, it takes me about an hour or two to sight-read a sheet of music. Largely because I have been too indolent to learn how to do it in real time (to use the technological parlance of our time) and because all I know how to play on my guitar are pentatonic scales and chords. O such a wasted existence! If only I had shown more initiative! If only I had known that more practice with an instrument would result in vaguely edible fruit!

But at least there’s karaoke to offer such a dubious surrogate. And at least there are the voices which assure me that reading is good and keep the deviant at bay so I can function in America’s troubling capitalistic system.

Terry and OGIC have fessed their comfort reading. I thought I’d add to the hue and cry, hoping that other swell folks would do the same. “Comfort reading” has been defined by our dynamic duo as anything that cools down an overheated mind. I’d stretch it a little further and define it as “anything that restores the mind back to its necessary default factory settings.” The following list is by no means a summation of my favorite writers, just the stuff that keeps me personally focused.

1. The Oz books — to restore imaginative settings.

2. Rex Stout — to restore careful balance between wiseass and logic.

3. James M. Cain — to cut the crap and get to the point.

4. Just about anything by Asimov, fiction or nonfiction (his history and science books worked wonders for me as a kid) — to describe things as clearly as possible.

5. Donald Westlake/Richard Stark — to get prose clean and subtextual.

6. Charles Dickens — to replenish color and description.

7. Terry Southern — to restore anti-establishment impulses and ballsiness.

8. John P. Marquand — to remind mind that satire comes in shades and can be accessible.

9. David Lodge — to encourage joie de vivre.

10. Ian McEwan — to respawn impulse to drown babies and revise brutally.

Crazed Hypothesis Which Involves Momentary Shift From Lit-Loving Guy Into Silly Marketing Type (With Extraordinary, Speculative Overtures) And Mischeviously Suggesting That William Goldman’s “Nobody Knows Anything” Maxim Applies to the Publishing World: If a 300-page novel is, by Page 165, something you’re trying to finish reading so you can move on to the next one, can you conclude it’s a good novel (if you admire it in spurts)? Conversely, if it’s something you can’t put down, does it follow that the book is a great one, whether pop or literary?

Is Page 165 is the make it or break it point? Sure, there’s the possibility that the story or prose will pick up in 5-10 pages. But if the reader or critic is not mind-staggeringly drunk over the book by now, then the writer can kiss her shot at being short-listed or getting a rave review goodbye, or face being a literary mid-lister. In which case you hustle the people behind the Today Book Club.

Is this how the publishing world works? Chaos theory?

Here’s where a bit of extremely specious speculation into American lit comes into play. If we examine the last five years of winners by page count, we find the following:

Pulitzer Fiction Winners

1999: The Hours by Michael Cunningham (230 pages)

2000: The Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri (198 pages)

2001: The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon (656 pages)

2002: Empire Falls by Richard Russo (496 pages)

2003: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides (544 pages)

Average: 424.8 pages

Next Awards Ceremony: May 2004

Of the Pulitzer winners, only The Interpreter of Maladies and The Hours are less than the around-500 page mark. And that’s only because The Interpreter of Maladies is a short story collection. My guess is that The Hours‘s uber-homage to Virginia Woolf led the page count factor to be dismissed. But the Pulitzers seem to favor sprawling epics, whether a Greek family coming to Detroit, two Jewish emigres making a killing in the comic book industry, or Russo’s wide blue-collar swath.

National Book Award Winners

1999: Waiting by Ha Jin (320 pages)

2000: In America by Susan Sontag (400 pages)

2001: The Corrections by Jonathan Franzen (592 pages)

2002: Three Junes by Julia Glass (368 pages)

2003: The Great Fire by Shirley Hazard (288 pages)

Average: 393.6 pages

Next Awards Ceremony: November 16, 2004

The National Book Award winners are more manageable reads, averaging out at the 350 page mark. But page count isn’t so much as a factor, as are consequences over time (World War II in The Great Fire, what happens to characters over a decade in The Three Junes, familial trappings in The Corrections).

The National Book Critics Circle Award

1998: The Love of a Good Woman by Alice Munro (352 pages)

1999: Motherless Brooklyn by Jonathan Lethem (336 pages)

2000: Being Dead by Jim Crace (208 pages)

2001: Austerlitz by W.G. Sebald (304 pages)

2002: Atonement by Ian McEwan (368 pages)

Average: 313.6 pages

Next Awards Ceremony: March 4, 2004

The odd one out here is The Love of a Good Woman, which is a collection of short stories. (And I’m discounting short story collections because, by definition, they’re harder sells than novels.) But it would appear that the National Book Critics prefer breezy, puncutated books with a more quirky style. Ian McEwan has a reputation for whittling his prose down to the bone. Austerlitz is “short,” but the conversations embedded within the novel require work to pick out, being separated by commas. Being Dead is, of course, the ultimate perspective novel in that it follows the disintegration of two corpses. And Motherless Brooklyn has the Tourette’s syndrome hook.

SILLY CONCLUSIONS:

The shorter your book, the more likely you’re going to win the National Book Critics Circle Award. But only if the prose is perspective-oriented and “challenging” enough to impress the critics.

If your novel is a little longer and your book is more centered around time and location, then you stand a shot at the National Book Award.

And if you have a sweeping epic, then the Pulitzer’s your best bet.

This leads me to wonder whether some publishers are more inclined to typeset their books to pander deliberately for specific awards, with abstruse cover art to match, and whether some editors, sensing that a prospective title has some literary merit (i.e., award-winning potential), will press the writer to tailor their books within these guidelines. (“No. Make it a little longer. And can we go off to Bavaria for a few chapters?”)

Of course, all of this is just extremely idle speculation on a rainy day. And I haven’t even taken a look at the finalists, or accounted for timed release dates. But being ill-informed on multiple levels about this sort of thing, I’d be extremely curious to hear from someone inside the publishing industry just how “pre-packaged” a particular book is for these three major awards. It certainly works that way with movies, and, since the risks are just as great (on a smaller financial scale) in fiction, it would seem to me that at least something along these lines would be in place in New York.

Just about every trade paperback edition that comes out has some kind of “Short-Listed” or “Finalist” nod on it, if it can include it. (Even a later edition of A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius had “Pulitzer Finalist” on it when it already had a built-in audience, which mystified me.) You’ll recall that Jonathan Franzen got his panties in a bunch over advertising the Oprah Book Club selection on the first hardcover edition.

So the questions are: Are we seeing a shift towards award-conscious releases (even in first editions)? (The more awards, the merrier.) And, if so, how embedded is this within current publishing house policy? And by what factual criteria do they base these ebullient cover-laden interjections?

The Guardian has a nuts and bolts profile of John Gregory Dunne, who passed away over the New Year’s weekend. A final novel, Nothing Lost, is planned for publication later this year.

Colson Whitehead’s next book has the man going crazy over New York in a collection of essays. Newsday doesn’t get much out of him, but it does note that Whitehead’s third novel is due out this spring. Oh, and he’s bought a home in Brooklyn with the MacArthur money. Hard reporting that boils down to this: Isn’t it good to be a hot, young thing?

Can you judge a book by its cover? New York book fetishists may want to check out the New York Public Library. Virginia Bartow has selected 90 books, trying to see if the books in questions can say something without being read. Included is Agrippa, a collaboration between William Gibson and Dennis Ashbaugh encoded in the first letters of DNA’s nucleic acids and a poem on a floppy disk that encrypts data upon access.

L. Frank Baum published two books in 1900. One was The Wizard of Oz, the other was The Art of Decorating Dry Goods Windows. Stuart Culver has a little more. Among Baum’s observations: “You must arouse in the observer cupidity and a longing to possess the goods you sell.” “Arousing the cupidity” didn’t actually work for Baum himself though. Most of his business speculations failed, but the Oz books did well.

And a moment of candor from the Post re: blogs? Or are they riffing with alt-weekly angst to keep up? Whatever the case, it’s a strange read from the paper of Woodward and Bernstein. (via Sarah)

[1/21/06 UPDATE: Dunne’s Nothing Lost (called by Kipen a “sloppy, fun swan song”), of course, was completely subsumed by Joan Didion’s memoir, The Year of Magical Thinking, which, like nearly every Didion nonfiction book, has gone on to win nearly every nonfiction award. And I should point out I’m just as defensive about blogs today as I was two years ago. I need to be more critical.]

British practitioners are tired of writing doctor’s notes. Apparently, there’s a rampant epidemic of comparative note shopping. This collection of notes, however, suggests that the aspiring malingerer might be better off forging their own. One note reads: “Both breasts are equal and reactive to light and accommodation.” Indeed. Unfortunately, doctor’s notes don’t make for compelling drama. That didn’t stop these guys from trying.

Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians has been a hoot, filled with some great reductio ad absurdum arguments: “Now, two propositions were accepted by both parties — that all infants are born in original sin, and their original sin is washed away by baptism. But how could both these propositions be true, argued Mr. Gorham, if it was also true that faith and repentance were necessary before baptism could come into operation at all? How could an infant in arms be said to be in a state of faith and repentance? How, therefore, could its original sin be washed away by baptism? And yet, as everyone agreed, washed away it was. The only solution of the difficulty lay in the doctrine of prevenient grace, and Mr. Gorham maintained that unless God performed an act of prevenient grace by which the infant was endowed with faith and repentance, no act of baptism could be effectual; though to whom, and under what conditions, prevenient grace was given, Mr. Gorham confessed himself unable to decide.”

What’s interesting is that a sizable chunk of Strachey’s papers can be found at the University of Texas at Austin. Who knew that such a pioneering iconoclast would end up where Bush II once presided as governor?

The Guardian has a list of 2003’s overlooked books. Plus, Crimson Petal author Michael Faber isn’t smitten with Motherless Brooklyn and Robert Louis Stevenson’s poetry is given a second look.

And, in a Maryland elementary school, comics are being used to get kids reading. Jim Trelease, author of The Read-Aloud Handbook (excerpts can be found here), is cited in the article as one of the inspirations. Among some of Trelease’s conclusions: He attributes the popularity of Harry Potter to a desire for plot-driven page turners. He sees human beings as pleasure-centric and believes that because of the greater likelihood of finding rare words in children’s books, reading narrows the word gap from the 10,000 words or so we use in conversation and the broader vocabulary that we don’t.

This whole gambit reminds me of that moment in David Lodge’s Small World where academics confessed titles they had not read. I’ll see Crooked Timber’s list, and raise the ante with more egregious not-reads, this year or any other year:

1. Anything written by Jhumpa Lahiri

2. Brick Lane by Monica Ali

3. Motherless Brooklyn by Jonathan Lethem

4. Anything written by the Believer ultra-vixens (Vida & Julavits)

5. The Bug by Ellen Ullman

6. The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon

7. Anything written by ZZ Packer

8. Anything written by J.M. Coetzee

9. Anything written by Jane Smiley

10. Anything written by Kinky Friedman

11. My Life as a Fake by Peter Carey

12. Bruce Wagner’s cellphone trilogy

Boo yah, baby! Take that!

Of course, I was too busy reading Quicksilver, catching up on William Faulkner, Virginia Woolf, Kevin Starr’s California Dream books, Robert Caro’s LBJ biographies, and Richard Powers, along with discovering folks like Frederick Prokosch and John P. Marquand, the latter now judged by the silly copy you see on his covers. (He ain’t delicious trash, baby. He’s a clean writer; a tad dated perhaps, but no less relevant. Write a novel more brilliant than Sincerely, Willis Wayde and then come back to me, darling.)

But, really, where do you people find the time to read all this stuff? What dimensional plane do you folks saunter off to? Or perhaps my rampant quasi-literacy has a lot to do with the fact that I’m attracted to big books, generally around 700 pages or so, written in microscopic fonts and requiring regular assualts on the unabridged.