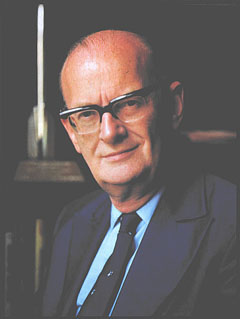

Nobody will replace Arthur C. Clarke. Not by a long shot. The inner cylindrical mysteries of Rama. The monolith concocted in collaboration with Stanley Kubrick. The sad calculated way in which aliens conquered the human race in the unforgettable Childhood’s End.

He was one of the last of the Golden Age giants. Born close to the end of one world war and becoming a man in the middle of another war, where he served with the Royal Air Force, Clarke looked to the stars and to his imagination, creating a body of work that will live on for decades to come.

I was a scrawny and curious kid who found him on the rackety stacks of an underfunded public library. My mother had gone through her second divorce. There wasn’t a lot of food in the house. There were holes in my T-shirts, and no money. But then one Saturday afternoon in the library, I opened up a musty volume and discovered these amazing words:

The next time you see the full Moon high in the south, look carefully at its right-hand edge and let your eye travel upward along the curve of the disk. Round about two o’clock you will notice a small, dark oval: anyone with normal eyesight can find it quite easily. It is the greatest walled plain, one of the finest on the Moon, known as the Mare Crisium — the Sea of Crises. Three hundred miles in diameter, and almost completely surrounded by a ring of magnificent mountains, it had never been explored until we entered it in the late summer of 1996.

The story, of course, was “The Sentinel.” And I read it all in one gulp. I took to craning my head out the window late at night when nobody was looking, spying during hours when nobody knew I was awake. And I did catch a pockmarked indentation, wondering if this was indeed the Mare Crisium. (A later look at a picture book on the moon confirmed that this wasn’t quite the case. But I took to calling any detail I could see a Sea of Crises, for reasons that were comical to me.)

The story, of course, was “The Sentinel.” And I read it all in one gulp. I took to craning my head out the window late at night when nobody was looking, spying during hours when nobody knew I was awake. And I did catch a pockmarked indentation, wondering if this was indeed the Mare Crisium. (A later look at a picture book on the moon confirmed that this wasn’t quite the case. But I took to calling any detail I could see a Sea of Crises, for reasons that were comical to me.)

And I became indebted to Mr. Clarke for granting me a grand galaxy of awe, intrigue, and possibility. This was needed. Because at the time, my universe was quite limited.

So Clarke’s death came as a tremendous blow to me. I never got to meet him. Never got to thank him. Never got to tell him that he helped some kid get through a turbulent time.

And I really have nothing more to say.

Arthur C. Clarke, thanks for being there when I needed you.

[…] great eulogies for Arthur C. Clarke. Here and […]

Everyone relax. There’s no one out there. We are all alone on this ball of mud that is hurtling towards the sun. This planet is a prison and we’re never getting out.

Not to date myself (meta-incest, anyone?), but I saw “2001: A Space Odyssey” when it first came out, when I was ten (already a seasoned reader of such things as Asimov’s Foundation epic). Being ten, I had no problem “getting” the movie, but I was already a devoted fan of Arthur’s, who, along with Isaac and Harlan, had taught me not only to read, but to dream. Arthur’s specific contribution to the mix was his proof-by-example that a “geek” could also be quite worldly and suave; a world-traveller, canny about global politics and hip about stuff like tailors, restaurants and hi-tech hardware.

He was anything but the typical, atrophied, shut-in handcuffed to a typewriter in a musty room (well, neither was Ellison, but Ellison was *too* hip, and made me think of the kids who wanted to kick my ass at recess… laugh!). Arthur Clarke made writing seem like a very cool thing to do.