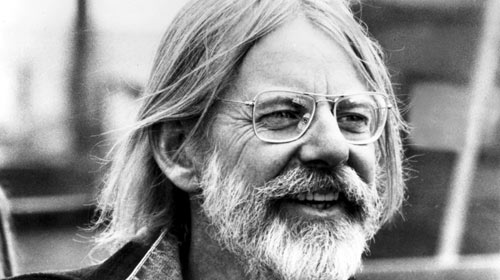

There were nearly one hundred and fifty souls at the Harvey Theater two nights before Thanksgiving. Outside, it was just a few degrees south of fifty degrees Fahrenheit. Inside, the writer Gary Shteyngart waited to be roasted with the heat of a thousand suns and the pain of a million overwrought metaphors.

Shteyngart was introduced by John Wesley Harding (aka Wesley Stace) with a slideshow of great Russian writers as “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” played over the speakers. Harding, who may or may not have been pretending to be British, had big gray eyes bulging with murderous suggestion in the dark. Presumably, this was one pivotal characteristic which had secured his role as host. He was keen on nouns which connoted human tragedy.

“And what has this incredible legacy of suffering,” boomed Harding into the mike, “what has this incredibly legacy of suicides, what has this incredible legacy of gulags, repression, this legacy of bubonic plagues, of famines, of forced labor camps calling for a revolution? What has this legacy given birth to, ladies and gentlemen?”

This was followed by a slide of Shteyngart, with a bottle of champagne and a pig. Yet there was neither Dom Perignon nor a prize porcine specimen circulated on stage. The audience learned later that animals were forbidden. It was believed that some clever person at the Brooklyn Academy of Music had induced this prohibition because someone would have to pay these wild beasts a performance fee. Whatever the reason, this callous ban had prevented Shteyngart’s beloved dachshund, immortalized through an endless concatenation of photographic pride on Twitter, from making his stage debut.

The four panelists emerged from their hidden positions: Kurt Andersen settling into a seat on stage right, followed by Sloane Crosley in a purple top, Edmund White in dapper suit and cane (the only figure among the quartet who came with a prepared list of barbs, which including a funny blurb for Mein Kampf that he let loose later in the evening), and New Yorker fiction editor Deborah Treisman in red boots so striking in hue that one wondered if she had spent half the day kicking in the teeth of MFA aspirants who hoped to enter her estimable pages.

Then there was Gary Shteyngart, clad in an evening jacket a few sizes too big and purportedly donned for the second time in his life. This ostensible target of wit and no-holds-barred barbs seated himself in a tiny wooden chair designed for a small child. He remarked almost immediately on his ass. This was an understandable fixation, given the chair’s regrettable physical dimensions. Mr. Shteyngart was to mention his backside two additional times over the next hour.

The evening wasn’t really a roast. The format was more Q&A, with Harding asking questions of the panelists, often unfolding an inquiry into a biographical multiple choice option which permitted an audience member to stand on stage with a winning raffle ticket that had been painfully extracted from the staple in the top right corner of the program. The queries felt more like vaguely invasive biography rather than outright ridicule. The barbs, if they can be called that, were mostly kind. Much of the time was devoted to apparent outtakes from Shteyngart’s two book trailers for Super Sad True Love Story, although it was noted early on that the artifact-laden footage had been shot on an iPhone.

This was a pro-Shteyngart crowd. When the collected spectators were asked if there had been anybody there who had never read a word of Shteyngart, a few handfuls of people raised their hands. Gary Shteyngart proved to be a brand name. One does not have to read his books to comprehend his imposing and often cardiac arrest-inspiring influence in the literary community.

The evening was mostly pleasant, especially when Shteyngart was presented with material to react to (such as his physical recreation of the non-Jewish walk from The Russian Debutante’s Handbook, that fabled first book that Shteyngart referred to as The Russian Debutante’s Handjob). Shteyngart appeared to be grateful for the company, both on stage and off, and talked largely in his natural métier rather than the clueless immigrant character who had charmed half the world on YouTube.

This was also the first public event in which Shteyngart’s prolific blurbs were given an official tally, although the number was as suspiciously pat as a late career Tony Scott film title. Presumably, the paying crowd had earned the right to learn that Shteyngart had blurbed 123 books. Shteyngart had not remembered the first book he blurbed, but he believed that his maiden blurb involved California in some way. The massive screen behind the stage mimicked Shteyngart’s blurb prolificity by running a rolling set of credits with the blurbs and the titles, although this reporter noticed several key blurbs missing (such as Benjamin Anastas’s Too Good to Be True). It remains unknown if the people who put this show together had obtained the vital details from Jacob Silverman’s invaluable Tumblr or an independent investigation. This reporter is too occupied to summon his inner Seymour Hersh. He is, in fact, trying to thaw a turkey at the last minute while writing this report.

Of the four ostensible roasters, Kurt Andersen was notably the weakest, peeling off easily observed details about Shteyngart’s height, his immigrant experience, and early pictures of Shteyngart on the Web without bothering to build a story around this. Crosley was surprisingly laconic through much of the night, but she did call Shteyngart a hack with the relish of a dear friend. The clear star of the four was Edmund White, whose sharp and ribald wit led him to take more risks and elicit more laughs. When the conversation shifted to teaching, White said, “I teach at Princeton, where the students are too smart to actually go into writing. They all go into finance.” In describing the details of Shteyngart’s forthcoming autobiography, White said Shteyngart had called himself “the leading Eastern European pimp with a stable full of Russian whores built for all tastes.”

We leave more vulgar minds to speculate on the vital question of Shteyngart’s underworld connections. One thing was certain: wild horses couldn’t keep the appreciative crowd away from BAM on Tuesday night. Perhaps in five more years, the second Shteyngart roast will permit room for a dachshund.