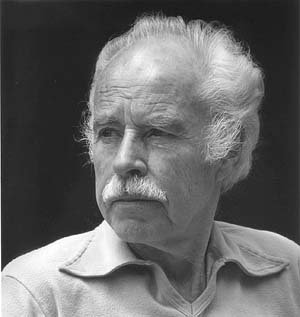

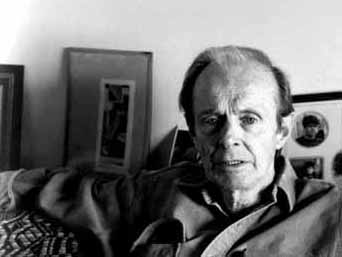

It’s the death day of Hubert Selby, Jr., who passed away six years ago on April 26, 2004. Selby died of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which was the sixth leading cause of death in 1990 and is well on its way to earning a solid position as the fourth leading cause of death in 2030. (Go lung disease! And don’t forget, fellow writers. Smoke ’em if you got ’em!) Selby’s wife, Suzanne, claimed that Hubert screamed and broke things when he wasn’t writing. This may explain, in part, the enhanced intensity and the staggered paragraph indentation of his best-known works: 1964’s Last Exit to Brooklyn (which features such street talk as “A couplea creeps wouldnt giveus the packages they got from home so we dumpedem. Im tellinya, we was real tight man”), 1971’s The Room, which deals with a criminally insane man recounting his past in a locked room, and 1978’s Requiem for a Dream, a fun-filled romp that involves broken families, drugs, and ECT. Selby later adapted Requiem with Darren Aronofsky (good man, one of the rare filmmakers who actually enlisted the writer) into an unsettling motion picture that has depressed several people and, for all we know, has inspired several suicides. Which is what great art should do sometimes.

It’s the death day of Hubert Selby, Jr., who passed away six years ago on April 26, 2004. Selby died of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which was the sixth leading cause of death in 1990 and is well on its way to earning a solid position as the fourth leading cause of death in 2030. (Go lung disease! And don’t forget, fellow writers. Smoke ’em if you got ’em!) Selby’s wife, Suzanne, claimed that Hubert screamed and broke things when he wasn’t writing. This may explain, in part, the enhanced intensity and the staggered paragraph indentation of his best-known works: 1964’s Last Exit to Brooklyn (which features such street talk as “A couplea creeps wouldnt giveus the packages they got from home so we dumpedem. Im tellinya, we was real tight man”), 1971’s The Room, which deals with a criminally insane man recounting his past in a locked room, and 1978’s Requiem for a Dream, a fun-filled romp that involves broken families, drugs, and ECT. Selby later adapted Requiem with Darren Aronofsky (good man, one of the rare filmmakers who actually enlisted the writer) into an unsettling motion picture that has depressed several people and, for all we know, has inspired several suicides. Which is what great art should do sometimes.

It was thought by many (or at least by the Dead Writer’s Almanac staff) that death would at long last secure the literary respect that had eluded Selby for so damn long. I mean, even a humorless stuffed shirt like Albert Mobilio thought to name-check Selby in (of all things) a 2000 review of a Simona Vinci book. But Selby isn’t quite on the level of Charles Bukowski. Epicene hipsters, often mumbling around in their early twenties, don’t seem to place his slim and gritty volumes upon their coffee tables to atone for a shortfall in streetcred and masculinity.

On the other hand, Selby was often thought “dead” even as he was alive. As he told an interviewer in 2002, “Yes, I’ve been given up for dead many times. In 1988, two doctors said that, according to all accepted medical evidence, I’m dead [enormous laugh].” (Somehow, the “enormous laugh” ensnared within brackets doesn’t truly convey the irony that Selby intended. But if you close your eyes for a smidgen, I’m sure you can imagine being marginalized and misunderstood.)

Selby was very clear to point out to liberal arts grads who skimmed his novels that the great American dream will “kill you dead. Striving for it is a disaster. Attaining it is a killer.” That he offered no alternative to the con is to his great credit. And it seems only fitting to end this installment with a clip of a very nervous Terry Gross attempting to soothe a man (“Because you were very sick….”) who merely needed his typewriter to negotiate the savage American wasteland:

Stay writing, don’t die too early, and keep in touch!