Peniel Joseph appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #318. Mr. Joseph is most recently the author of Dark Days, Bright Nights.

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Wondering if he lands on Plymouth Rock, or Plymouth Rock lands on him.

Author: Peniel Joseph

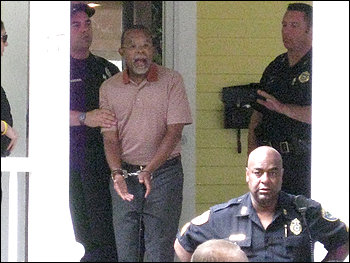

Subjects Discussed: Whether or not the bold declarations within Malcolm X’s “The Ballot or the Bullet” speech has been entirely heeded, the progress of African-American politics, revolutionaries vs. political pragmatists, Harold Washington, Jesse Jackson, Michael Eric Dyson’s critiques of Obama, Jeremiah Wright’s perception, Obama’s failure to confront race, the February 19, 2009 New York Post cartoon, race as portrayed in Obama’s speeches, the Henry Louis Gates arrest, whether the beer summit was more of a symbolic gesture rather than a practical confrontation, black revolutionaries being denied publication in prominent mainstream outlets vs. Stokely Carmichael getting published in The New Republic and The New York Review of Books, color-blind racism, the Nation of Islam’s bootrap and racial uplift strategies, Nixon seeing “black capitalism” as a promising prospect of Black Power, Fubu’s co-opting of Black Power slogans, black women and activism, misinterpretation of the Black Panther Party, the plasticity of ideology, Stokely Carmichael’s November 7, 1966 speech in Lowndes County, the fluidity of Black Power, Claiborne Carson’s In Struggle, Carmichael being wrongly accused of being the main influence on the SNCC Black Power position paper, misconceptions about Carmichael, Obama’s dismissal of Kwame Toure as a madman, the failure to celebrate Martin Luther King as a critic of American democracy, what Carmichael’s FBI file says about limited perspectives of black power figures, Carmichael’s antiwar stance, false government conclusions about Black Power, Tavis Smiley being taken to task for criticizing Obama, and prospects for new forms of Black Power radicalism.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: When Malcolm X delivered his famous “Ballot or the Bullet” speech, you point out that newspapers ignored his more tangible call for one million new black voters for a black nationalist political party. Now black voters, as we all know, were instrumental in getting Obama elected in November. I’m wondering though — because they were not necessarily black nationalists — whether Malcolm X’s call was entirely heeded.

Correspondent: When Malcolm X delivered his famous “Ballot or the Bullet” speech, you point out that newspapers ignored his more tangible call for one million new black voters for a black nationalist political party. Now black voters, as we all know, were instrumental in getting Obama elected in November. I’m wondering though — because they were not necessarily black nationalists — whether Malcolm X’s call was entirely heeded.

Joseph: Well, I think his call is going to be heeded into the next generation at least. When we think about when Malcolm said that in 1964, there was no congressional black caucus. There were no black senators since Reconstruction. There were no black governors. There wasn’t the wave of black mayors that we started having — starting in 1967, with Richard Hatcher in Gary, Indiana; Carl Stokes in Cleveland; by 1970, Kenneth Gibson in Newark, New Jersey. In the early ’70s — ’73, ’74 — you’re going to have Coleman Young in Detroit, Maynard Jackson in Atlanta. By 1983, you have Harold Washington in Chicago. And that’s the Chicago that Barack Obama comes of political age in at least — even though he grows up in Hawaii, he’s born in Hawaii on August 4, 1961. So I think African-American voters in the 1970s, in the 1980s, take heed to these politics of racial solidarity, for the most part. There’s going to be exceptions. People like Edward Brooke, the first black Senator elected in a general election in 1966 from the state of Massachusetts. Tom Bradley becomes Mayor of Los Angeles after the 1973 election in a city that only has 10% African-Americans. But for the most part, there’s really a racial script, where you’re going to get black elected officials in places like New Orleans. Mississippi becomes the state that has the most black state representatives and officials. It doesn’t have a senator. It doesn’t have a governor. But it has the most elected officials out of any of the states decades after the segregation of Freedom Summer and the assassinations of those three civil rights workers — Schwerner, Cheney, and Goodman; two white and one black.

So when we think about Malcolm’s call, it is heeded during the ’70s and ’80s. But as we get into the ’90s and the 21st century, there’s going to be some real notable exceptions. People like L. Douglas Wilder, who becomes governor of Virginia in 1989. People like Deval Patrick, who becomes governor of Massachusetts in 2006. People like Barack Obama, who becomes a Senator out of Illinois in 2004. People like Carol Moseley Braun, who becomes a Senator in 1992. So when we think about racial politics, the politics of racial solidarity for elections is still there. When you think about Bobby Rush, who Obama ran against in 2000 for the South Side of Chicago Congressional District, that’s a black district. Most likely, you’re always going to have an African-American representative there. So the politics of racial solidarity are there. But at the same time, there’s a new class of African-American elected officials. People like Cory Booker in Newark, New Jersey, who are really doing a pan-racial appeal. There’s saying, “Look, I’m an elected official. I am also black, but I happen to be black.” They’re not coming out in a very robust way talking about black solidarity and that the reason why I should be Mayor of Newark is because I’m black. Michael Nutter in Philadelphia’s the same way. Deval Patrick, the same way. Where they’re saying, “I happen to be black, but I’m going to be an elected official for all people.”

Correspondent: I’m curious if it takes someone like a Harold Washington or an Obama to create that one particular figure who both revolutionaries and those who believe in the pragmatism — revolution can be pragmatism too in its own ways — but those who believe in elected politics. Because there’s always been a fractiousness going on between the two within the black power movement of the last four decades, in particular. So does it take some brand new figure to unite? Or is it possible to have someone who can leave a legacy beyond the elected moment?

Joseph: Well, I’d say that it depends upon the time period. Because when we look at the late ’60s and early ’70s, black militants and black elected officials had real coalitions and ties. I think the best example of that is Amiri Baraka and Kenneth Gibson in Newark, New Jersey — and also the Gary Convention in March of 1972. The Gary Convention was a national black political convention attended by 12,000 people. And the co-conveners were Congressman Charles Diggs from Michigan, Mayor Richard Hatcher from Gary, Indiana, and Amiri Baraka, who held no elected position and who was just a black nationalist poet and an organizer. So there was this coalition. But by the middle ’70s, that coalition is going to fracture — really amid mutual recriminations. Politicians are going to accuse militants of being wild-eyed dreamers who don’t understand the politics of governance and the pragmatism that governance really precipitates. I mean, to be an elected official is to be somebody who is pragmatic and to compromise. Militants are going to accuse black elected officials of being the worst kind of sellouts. People who really utilize the politics of racial solidarity to get into office. And as soon as they get into office, they use the power of municipal politics and City Hall to enrich themselves and their cronies. And I think you’re going to see that tension over the next forty years. But there’s going to be notable exceptions. One is Harold Washington, who has a coalition of pragmatists and militants and somehow, in four and a half years as mayor, manages to please them all. Because Washington is re-elected and dies of a heart attack right around Thanksgiving of 1987, but is very much well-regarded in Chicago. Another mayor is going to be, surprisingly, Marion Barry of the 1970s. At least the initial Barry. So Barry, before the huge controversies over crack cocaine and adultery and all this different stuff, had militants and moderates in his camp. And he managed to please both of them.

Correspondent: A very [Adam Clayton] Powell-like resurgence as well.

Joseph: Absolutely. Absolutely. And when we think about militants and moderates in the 2008 presidential election, you saw the social movement that surrounded Obama draw in pragmatists. And it also drew in revolutionaries. So sometimes you do see these transcendent figures. And, finally, the best example in the 1980s of that is Jesse Jackson. Jesse Jackson runs for President in ’84 and ’88 — really inspired by what Harold Washington was able to do. And Jesse gets three and a half million votes in the Democratic primaries in 1984. Seven million in 1988. And he really inspires both pragmatists and militants in that campaign.

Correspondent: But inevitably there still remains a fractiousness — possibly tied in, in Obama’s case, with the failure to discuss race, which you bring up in the book and which Michael Eric Dyson recently appeared on MSNBC in response to the Harry Read fiasco, pointing out that Obama was “a president who runs from race like a black man runs from a cop.” You point out, in your book, that Obama’s reluctance to embrace race is especially ironic in light of the fact that he has a public admiration for Lincoln. You note that “his appreciation remains a simplification in as much as it largely fails to deal with the sixteenth President’s extraordinarily complicated racial views.” So the question is whether that observation and Dyson’s remarks come from the same particular place. Does Obama’s many political compromises — which we were talking about earlier, the necessity of being a politician — essentially make his failure to confront race untenable?

Joseph: Well, it’s very interesting. I think that we’re living in a time period in which politicians can talk about race in a less open way than forty years ago. And I think that’s interesting. Because we usually think of progress as something that’s linear — it’s a linear narrative. So if it’s 2010, we should be able to talk about race better than we could in 1968. That’s not true in this case. We can talk about race in the late ’60’s in a much more candid way because of the civil rights act, because of the voting rights act, because of the race riots that we’re going on, because of the Kerner Comission. The New York Times used to be an organ in the late ’60s and early ’70s, where you had black militants who had a podium in the New York Times, were writing op-eds about black thinktanks and about the Gary Convention. The Washington Post was the same way. In a way that we would find — our generation — extraordinary. Because those august institutions won’t give black militants that kind of platform anymore. So the President of the United States, in terms of Barack Obama, one of the reasons why he won, race was a positive and a negative. It was a positive in the sense that, for a whole new generation of voters, especially those under 30, they found it quite refreshing that this man was running for President and took him very seriously. It was a negative, as we saw in the case of Jeremiah Wright, when critics of Obama, especially the right wing, could connect him to what was perceived as black extremism and anti-American sentiment. Including things like the Black Power movement. Because Jeremiah Wright is certainly coming out of a tradition of black liberation theology, which is rooted in that black power movement. People like James Cone. People like Reverend Albert Cleage out of Detroit. So I understand Dyson’s critique and, on some points, I actually agree with Dyson’s critique and others.

BSS #318: Peniel Joseph (Download MP3)