DO NOT SELL AT ANY PRICE

by Amanda Petrusich

Scribner, 272 pages

Earlier this year, the journalist John Jeremiah Sullivan revealed an unethical streak by invading the home of blues historian Robert “Mack” McCormick and pilfering photographs and personal items that the octogenerian autodidact had painstakingly acquired over decades and generously shared. McCormick’s health was fragile, but that didn’t stop Sullivan who, with the conquistadoral impulse of Joe McGinniss cracking open William Styron’s special sealed crab meat to make an omelette, happily appropriated McCormick’s findings for a New York Times Magazine cover story.

When outsiders commit such brash invasions under the guise of “journalism,” one tends to hold a certain mistrust towards those working the same territory. But I’m pleased to report that Amanda Petrusich’s Do Not Sell at Any Price (which comes saddled with a Sullivan blurb) is a more sensitive and fair-minded portrayal of 78 record collectors and blues enthusiasts. Petrusich is kind but keeps her distance. She does not encroach upon or judge her subjects, never painting them as freakish. She heeds their advice and is never condescending, even when they belch in her face.

This courteous approach allows her to unpack bountiful history — such as the rise and fall of Paramount Records, one of the biggest producers of records featuring black performers in the 1920s and the 1930s — and behavioral insight into this winning group of passionate enthusiasts. We get a good sense of how collectors exuberantly grill each other like “two high-achieving middle school students” over recent purchases and learn of the harrowing fog-shrouded drive into the Shenandoah Valley. Because some sessions weren’t recorded at the precise speed of 78 rpm, collectors have adopted such homespun remedies as affixing a Popsicle stick near the needle to get a more lucid and robust playback. We are privy to the common expertise shared between knowledgeable collectors and ethnomusicologists, with both offering theories over whether or not Kid Bailey Brunswick is Willie Brown (“imagine Willie Brown singing toward the top of his range maybe on a day when he wasn’t stirred up by alcohol and rowdy buddies in the studio”). Along the way, Petrusich is candid enough to contend with her own music listening issues as a young critic:

I’d dutifully memorized facts about amplifier settings and pedals and filters and microphones and producers and years of release, even when it felt depressing and hollow, like I was methodically teaching myself exactly how to miss the point.

The vital question of what happens to our brains when we listen to music has been vigorously pursued by Daniel Levitin, but Petrusich’s declaration does lead us wondering about the collector’s temperament. Why do some people become full and rejuvenated when basking in the meticulous details? Is there something about the visceral lawlessness of old time blues that makes them feel music differently? Does collecting or wallowing in the obscure fulfill a human need to master the world, whether as an action of an expression of expertise? Or is it a trap, comparable to Borges’s “The Library of Babel,” where obsessive collection results in inevitable despair or destruction? Petrusich levels, by her own admission, some shaky Asperger’s charges near the end of her book, but her vivacious reporting is better at answering these questions more than any armchair psychoanalysis.

There are fruitless trips to flea markets, a journey to the NYPL Performing Arts branch to explore its 78 collection, and, most exotic, an elaborate scuba diving expedition (complete with Petrusich taking classes) to seek out the potential remains of old records at the bottom of the Milwaukee River, recalling William T. Vollmann’s obsessive search for Mexicali tunnels in Imperial. This vicarious approach shows how the hunt for something esoteric attracts a peculiar yet essential type of person who faces unanticipated responsibilities. Petrusich meets Nathan Salsburg, who helped to salvage the hillbilly 78s of another collector just as they were being dumped, buried in a mess of ketchup and trash, which included a rare recording of a throat-singing cowboy. When Peterusich attempts to wade through this dead collector’s correspondence, she is at a loss to pinpoint the methodology behind his passion. The documents that collectors leave behind may not be sufficient enough to convey the motivations that triggered the pursuit. The burden falls on those who fall in love with the music (or the collecting bug), willing to make the lifelong plunge to keep something appreciated by a diminishing subculture alive.

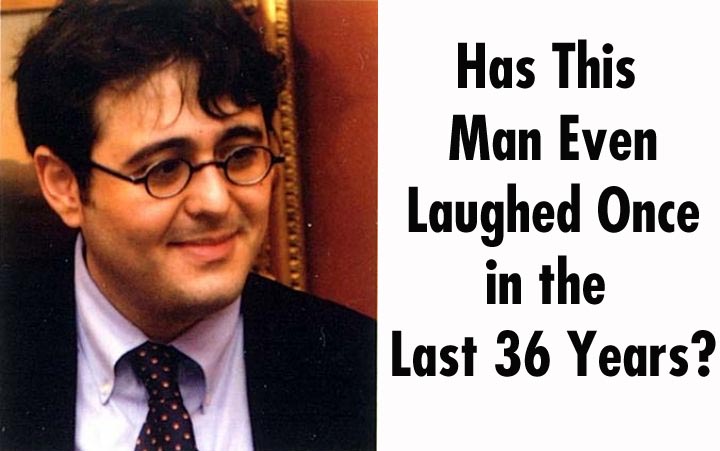

Much ink is rightfully spilled about Harry Smith, the eccentric filmmaker behind the six-album Anthology of American Folk Music, arguably the playlist to end all playlists. Smith’s grand collection, pulled from his mighty stash of blues and country 78s, represents the clearest example of a collector leaping from formidable obsessive to influential tastemaker. But Petrusich is taken with how Smith’s “face is approximately 80 percent glasses” and how he “appears to be about ten thousand years old.” Who cares for the preservationists and the collectors? They are quietly celebrated for their tastes, but maybe they deserve something louder and more human than mere gratitude. Petrusich’s book is a good start.