Pico Iyer’s anti-intellectual review in today’s New York Times Book Review begins with the sentence: “I confess, dear reader: I’ve always had a problem with William T. Vollmann.” This raises the question of why Iyer was even assigned the review in the first place. Certainly, Iyer is a widely revered travel writer, a man who has called himself “a global village on two legs.” His peripatetic escapades might be viewed, by those who rarely step outside Manhattan’s boundaries, as an able match to Vollmann’s. But in pairing Iyer up with Vollmann, the NYTBR‘s has once again demonstrated its crass commitment to useless criticism, stacking the deck against writers who do anything even a little idiosyncratic or anyone who sees the “global village” as one with broader possibilities.

The New York Times is supposed to be the Paper of Record. But in assigning a critic who is already dead set against the author he is writing about, a critic who, in this review, deploys his loutish prejudices in a manner comparable with a fulminating Tea Party protester, the Times reduces itself to a crazed right-wing pamphlet put together in a gun nut’s garage.

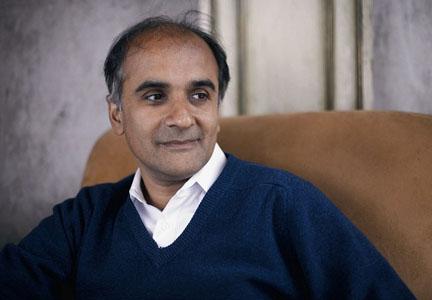

But here’s the thing. Pico Iyer isn’t a crackpot. He’s a distinguished critic who has cogently wrestled with William Buckley’s oeuvre and written about Tibetan movies for The New York Review of Books. But in accepting the assignment and alerting the assigning editor of his tastes and conflicts of interest, he has sufficiently announced that he’s no longer interested in being taken seriously. He has reduced himself to some dime-a-dozen snark practitioner: that old guy sitting in a lawn chair with a six-pack and a shotgun, spitting out a homebrewed fount of crass and uncomprehending commentary. Iyer has become just as culpable in debasing the New York Times Books Review as the usual gang of sophists. He claims in his review that Vollmann’s “paragraphs…seem to last as long as other writers’ chapters [and] can suggest a kind of deafness and self-enclosure.” But anybody who has read Iyer’s Sun After Dark (as the NYTBR‘s editors surely must have) knows how much Iyer objects to “long sunless paragraphs.” So why assign him a book with prose that he will never enjoy? If he hoped to challenge his inflexible assumptions about Vollmann, surely there was a more dignified way to go about it.

Before I demonstrate why Iyer’s review is so wrong, and why he cannot even cite Vollmann’s passages correctly, I should probably offer a disclaimer here that I’m a great admirer of William T. Vollmann’s work. I’ve interviewed him twice. I believe Imperial was a needlessly condemned masterpiece. But I’m not a blind zealot who believes that every sentence that Vollmann is gold. (I have problems with The Butterfly Stories, and I offered a respectful pan to Poor People in the Los Angeles Times). Still, Vollmann is not a writer to dismiss lightly. In The Ice-Shirt, Vollmann nearly froze to death in Alaska to know what it was like to shiver. In Imperial, he chronicled a California territory that is not likely to see such dutiful attention again in our lifetime. He has been in war zones. He has seen friends and family die, and written movingly about it. He has charmed his way into circumstances that puffups like Pico couldn’t begin to fathom from a gutless perch. And he’s remained a committed talent who has skillfully weaved these experiences into several unforgettable books. He’s won a National Book Award for Europe Central. Love him or hate him, there is simply no other American writer who has, over the course of more than twenty books, written with such unusual style and verve on so many variegated topics.

So when Iyer calls Vollmann’s obsessiveness “almost demented,” what makes this any different from calling Vollmann himself “almost demented?” “Obsessiveness” is indeed one of Vollmann’s qualities as a writer. And Iyer’s statement is nothing less than an ad hominem attack. (Sam Tanenhaus, of course, would tell you otherwise.)

But Iyer is also a stupendous misreader, a man who misquotes from the opening sentences of chapters, often conflating one sentence with another. He claims that Vollmann declares himself an “ape in a cage” because “he cannot understand a word.” But let’s study the context context of what Vollmann actually wrote, in the sentences that opens the second chapter (not the book’s opening sentence, as Iyer deliberately misleads):

This book cannot pretend to give anyone a working knowledge of Noh. Only a Japanese speaker who has studied Zeami and the Heian source literatures, learned how to listen to Noh music and wehat to look for in Noh costumes, masks and dances could hope to gain that, and then only after attending the plays for many years. Zeami insisted that “in making a Noh,” the playwright “must use elegant and easily understood phrases from song and poetry.”…But century buries century, and the performances refine themselves into an ever noble inaccessibility, slowing down (some now require at least double the time on stage that they did when Zeami was alive), evolving spoken parts into songs, clinging to conventions and morals now gone past bygone; as for me, I look on like an ape in a cage.

In other words, Vollmann is clearly delineating Noh’s great complexities, aspects that are difficult even for a native Japanese speaker to entirely ken (and that Iyer clearly has no curiosity to understand; he proudly proudly boasts about “the very dramas that have often sent me toward the exit before the intermission”). But if Vollmann is “an ape in a cage,” he is pointing out, with sincere humility, that neither he nor any audience member can ever hope to reach the civilized heights of a noble art form.

Iyer suggests that Vollmann’s “comparison” of Kate Bosworth with Kannon zany, but fails to comprehend that Vollmann has a larger goal. Here he is discussing Bosworth:

Her skin is a flawless blend of pinks; I suppose it has been powdered and airbrushed. Her mascara’d gaze beseeches me with the appearance of melancholy or erotic intimacy. Her mouth pretends to say: “Kiss me.” This professional signifier appears on many women in pornographic magazines and in the long slow sequences of romantic films. For some reason, I rarely see it on the faces of strangers in the street. (127)

It’s clear from this passage that Vollmann is attempting to place Hollywood magazine representations within the context of Noh. And, true to form, Iyer continues to take Vollmann out of context, implying that Vollmann’s confession about loving woman is (a) related to the above exchange and (b) related to the manner in which he asks Hilary Nichols, “Who is a woman?” (Actually, the “loving woman” sentence occurs on page 110, in a chapter on Noh faces, having little to do with either of the subjects from which Iyer draws his false associations. That Iyer ascribes Vollmann’s private sentiment to what he says to some woman in the bar indicates that not only is he unskilled to write this review, but that he has no real clue about the conversations that actually occur in bars.)

He attempts to accuse Vollmann of hypocrisy by pointing to his “extravagant” spending in Kissing the Mask, after writing Poor People. But lacking the ability to understand that a book on Noh theater is entirely different from one on poverty, Iyer fails to note that Vollmann confessed in Poor People that (a) he was “sometimes afraid of poor people,” (b) he is “a petty-bourgeois property owner,” and that (c) he has been mostly transparent about noting when he has paid an interview subject or how much one of his chapters have cost.

So if the Oxford English Dictionary had a listing for “incurious elitist with a hatchet and an agenda,” Pico Iyer would take up the entire entry. It says something about Iyer, I think, that his review can’t even make a civilized case against the book he so clearly loathes, that the manner in which he strings together so many unrelated items has no singular critical thrust. Reading his review is like watching an autistic fire a submachine gun in an upscale shopping mall. When Iyer claims, bizarrely, “that reading for more than 30 minutes at a time can induce headaches, seasickness, and worse,” and fails to qualify this observation with specific experiential examples, you get the sense of a desperate man without streetcred struggling to take a piss in an alley when his experience is limited to Larry David-style sitdown techniques confined to palatial restrooms.

No, it’s Iyer here who’s the one who fails to grapple with the big questions. Perhaps what truly motivates Iyer’s review is that, despite all of Iyer’s travels, he’s never quite found the courage or an interest in people outside his comfort zone. Here’s Iyer writing about Dharmamsala in The Open Road:

The people who were gathered in the room, maybe thirty or so, were strikingly ragged, their poor clothes rendered even poorer and more threadbare by their long trip across the snowcaps. They assembled in three lines in a small space, and all I could see were filthy coats, blackened faces, sores on hands and feet, straggly, unwashed hair.

Now here’s Vollmann writing a man named Lupe Vasquez in Imperial:

For an eight-hour job, it’s forty-five bucks. When I first started, in the early seventies, I used to make about seventeen bucks a day. Two-fifty an hour times eight hours is what? [Footnote: It would have been twenty dollars.] With taxes you take home about seventeen, eighteen bucks. I’d say the work’s the same now; it’s the same. [Footnote: I wish you could have heard the weariness in his voice as he said this.] Maybe the foremen don’t hurry you up and treat you as bad as they used to. We were scared, you know. We had to hurry up. For the foremen, money is more important to them than their own people. They gotta kiss ass, and the way they do that is by making us work harder.

Unlike Iyer, Vollmann actually provides tangible testimony on what it is to be poor, and what it is to live poor. Iyer, by contrast, is a vapid and unconcerned tourist who will never comprehend much beyond an impoverished man’s look. Still, I’m confident that none of my quibbles with Iyer’s incompetence will deter this bourgeois monster from writing. And that’s just fine. Because when future readers want to know about the world that we live in, when they wish to feel thrill, passion, and horror about the late 20th and early 21st centuries, my guess is that they’ll go to Vollmann before even flipping through Iyer. Unless, of course, they’re the types who, as Mel Brooks once satirized, call for the pissboy instead of understanding that even the pissboy has a soul.

[UPDATE: Over at The Constant Conversation, John Lingan also addresses Iyer’s review, pointing out that the piece fails to address the basic questions of arts criticism: “How about engaging the man’s ideas head-on, and not simply expressing your mild distaste with the presentation?”]