On August 6, 2011, The Los Angeles Review of Books‘s Tom Lutz published an essay about the future of book reviewing suggesting some evolution of “old-school commerce” through a somewhat questionable “private philanthropy.” Rightly decrying The Los Angeles Times‘s recent decision to cut its entire freelancing budget devoted to books coverage (which included Susan Salter Reynolds, ignominiously diminished from staff position to freelancer in order to save her corporate employer of twenty-three years some money), Lutz lamented “the agonizing death of print journalism” while also expressing his hope that his own outlet could “raise the money from foundations, private individuals, and advertising to reemploy at least a few of the people who have been washed out to sea by the seemingly endless waves of firing and cutbacks in the print world.”

Lutz further claimed that there was “a missing generation of journalists” — with the last “youngster” at the Times being Carolyn Kellogg in her mid-forties. What Lutz failed to observe, however, was that Kellogg was plucked from the online world. What he also did not acknowledge is that The Los Angeles Review of Books is not a print outlet, but an online one. And while the quality of Lutz’s stewardship has been commendable so far — especially his recent efforts to find new regular perches for both Reynolds and Richard Rayner (another Times freelancer let go) — he has failed to be transparent about the degree to which he is paying his contributors. He has indicated that The Los Angeles Review of Books has “raised about 10% of what we need,” but he has not offered a specific dollar amount, much less any revenue-generating plans outside of selling T-shirts and tote bags.

Financially speaking, The Los Angeles Review of Books is no different from any other group blog or online magazine. As Full Stop‘s Alex Shephard observed, the question of basic survival is crucial to all writers, regardless of where they come from. The Los Angeles Review of Books‘s present interface relies on Tumblr and, even though it has featured close to 100 posts, it is just as dependent on volunteers and donated time as any other online outlet. As such, so long as it does not pay, it assigns zero value to the labor of its contributors, which makes it not altogether different from The Huffington Post.

Lutz’s biggest oversight — a blunder likely inadvertent, but one nevertheless insulting to the many journalists currently toiling online for free — was his failure to acknowledge the countless outlets that have sprouted up in response to a diminishing book reviewing climate. Missing generation of journalists? What of The Millions, The Rumpus, Full Stop, The Quarterly Conversation, the reviews recently introduced at HTML Giant, Open Letters Monthly, the monthly reviews over at Bookslut, Words Without Borders, and other quality outlets too numerous for me to list? Reynolds, Rayner, and Sonja Bolle have certainly read a great deal. But what of the twin deaths of Ed Park’s science fiction column (Astral Weeks) and Sarah Weinman’s mystery column (Dark Passages)? Both of these serious readers disappeared only a few months before the latest assault on Times contributors. Even if Park and Weinman were discouraged from continuing their vital columns, walking away from their respective gigs because of frustration with those running the show, they were nevertheless victims of the Los Angeles Times‘s ongoing war against books coverage. Real editors would have committed themselves to keeping Park and Weinman on board. And what of Reynolds’s comment at this Publishers Weekly article?

I offered to continue writing for very little money until things got better. Also the quote about continued commitment is insulting to readers’ intelligence. When I was laid off a year and a half ago I was assured by the editor of the book section that it was purely cost cutting and there would be no more hires. Next thing I knew he had become the book critic and then they hired a full time blogger one month later. I understand these are tough times but isn’t publishing a world in which expertise has some value?

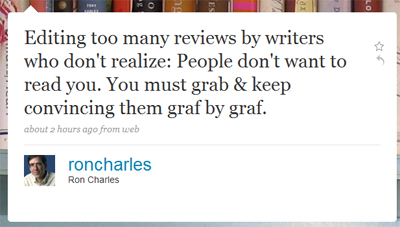

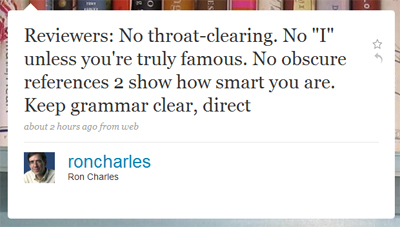

Lutz’s essay is unwilling to swallow the bitter pill: in a world of free, expertise no longer has any value. The National Books Critics Circle can hold all the panels it likes about the state of book reviewing, but this clueless organization of ostensible professionals refuses to comprehend the present journalistic environment. On the books front, there are few places left for paying journalists.

Are times now so tough that we cannot find ways to prop up our peeps? Don’t journalists or books experts deserve to be paid for their work?

The above video, featuring the angry writer Harlan Ellison, has been watched more than a half million times on YouTube. In it, Ellison rightfully points to the fact that most writers offer their services for free and that he, as a professional, has been “undercut by all the amateurs.” Ellison, much like the majority of book reviewers left coughing in the dust of recent cutbacks, faces a ramshackle system in which those who want the content are so used to getting it for free that they expect writers of all stripes to surrender their labor for nothing.

While the many book websites I have mentioned above continue to offer quality material, the writers who spend their hours carefully reading books and carefully writing essays quietly turn in their work. They cultivate relationships with editors, hoping that their endless apprenticeships will eventually lead to stratagems that cover some sliver of the rent.

Meanwhile, those at the top continue to show no interest in offering a break or two to the next generation. But they are all too happy to lead them on. Organizations such as the NBCC offer “freelancing guides” as an incentive to woo a declining membership, while hiding the fact that The Believer only pays $75 for a review (and takes as long as two years to pay some of its contributors) and that the Boston Globe pays as little as $150 for a review. The dirty little secret is that freelancers get paid hardly anything. A fortuitous freelancer can count on a sum just under $200 if a review is commissioned by the Dallas Morning News, the San Francisco Chronicle, or the Philly Inquirer. But shouldn’t one expect more from three of the top 50 United States newspapers? If we translate that $200 into labor — let’s say that it takes about fifteen hours to read a book and five hours to write the review — the freelancer basically earns around $10/hour before paying taxes. You could probably make more money working at a touchless car wash. Small wonder that so many, including yours truly, have dropped out of this dubious racket, leaving it to increasingly sour practitioners. Book reviewing has reached a point where those who are left practically have to beg editors to get into a slot. And if book reviewing has become a vocation in which veteran and novice alike must debase themselves for scraps, one must legitimately ask if there’s any real point in such an uncivilized and undercompensated trade carrying on. Perhaps, like the ending of Barry Lyndon, it comes down to this: “good or bad, handsome or ugly, rich or poor, they are all equal now.”

The author in question is William T. Vollmann. And the book is Riding Toward Everywhere, a surprisingly thin volume (by Vollmann standards, at least) that concerns itself with trainhopping and vagrants. (Full disclosure: While the book isn’t Vollmann’s greatest,

The author in question is William T. Vollmann. And the book is Riding Toward Everywhere, a surprisingly thin volume (by Vollmann standards, at least) that concerns itself with trainhopping and vagrants. (Full disclosure: While the book isn’t Vollmann’s greatest,  It is clear here that Vollmann is being as straightforward as he can about his life, trying to set down personal fallacies he may have in common with his subjects. It would be one thing if Ms. Denfeld stated the precise problems she had with the book, but she remains so fixated in her happy little universe — which involves living with her partner with three adopted children and OMG!

It is clear here that Vollmann is being as straightforward as he can about his life, trying to set down personal fallacies he may have in common with his subjects. It would be one thing if Ms. Denfeld stated the precise problems she had with the book, but she remains so fixated in her happy little universe — which involves living with her partner with three adopted children and OMG!