(This is the first entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1.)

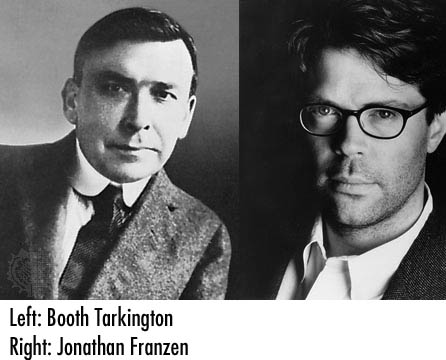

By all reports, Booth Tarkington was hot shit sometime in the early 20th century. It is quite possible that he was the kind of man who entered a room and announced with his very presence: “Do you know who I am?” How do we know this? Well, he won the Pulitzer Prize twice (for Ambersons and Alice Adams). He had family members who were politicians (his uncle, Newton Booth, was the eleventh Governor of California and a United States Senator) and Tarkington himself was elected to the Indiana State Legislature.

By all reports, Booth Tarkington was hot shit sometime in the early 20th century. It is quite possible that he was the kind of man who entered a room and announced with his very presence: “Do you know who I am?” How do we know this? Well, he won the Pulitzer Prize twice (for Ambersons and Alice Adams). He had family members who were politicians (his uncle, Newton Booth, was the eleventh Governor of California and a United States Senator) and Tarkington himself was elected to the Indiana State Legislature.

I have consulted a hagiography written by someone named Robert Cortes Holliday, a “biographer” who appears to be just as dead as Tarkington. Holliday informs us that Tarkington was very precocious as a child: “His oddities, one gathers, were even more odd than is usual with odd children.” Which begs the question of what “even more odd than is usual” meant in 1873. Did it mean that Tarkington was a pyromaniac? A toddler who tortured ants through a burning-glass? I shall leave these questions to the scholars. What’s particularly strange about this description is that Holliday, apparently grabbing direct quotes from the mack daddy himself, claims that Tarkington was “not precocious at all” after the age of four. Since most of us don’t really remember much before the age of three, there remains the vital question of whether Tarkington was the right man to remark upon his own precocity. A critic named Eleanor Booth Simmons (a Booth related to Booth Tarkington?) has this to say in the now forgotten periodical The Bookman: “Mr. Tarkington has that peculiar artistic sensitiveness which leads him, whether consciously or unconsciously, to meet each new subject with a new and subtle and fitting change of mood.”

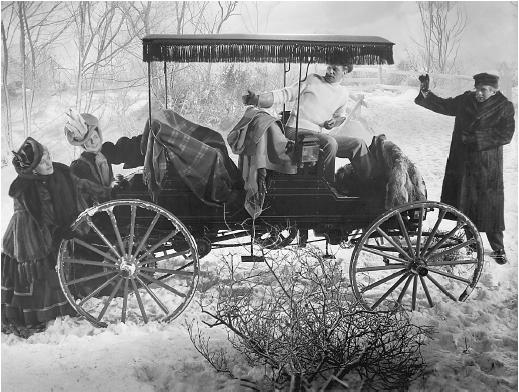

All this talk of precocity and artistic sensitiveness led me quite naturally to Orson Welles. I must confess that before reading this book, I had not read Booth Tarkington before. I had obtained an ancient hardcover edition of Seventeen (with an impressive green cover!) at an estate sale, but hadn’t bothered to dig in. I had only been familiar with Orson Welles’s film version of The Magnificent Ambersons and, perhaps more prominently, the sad story behind it. RKO sent Orson Welles off to Brazil to work on another project. Since Welles relinquished his right to final cut, RKO took the opportunity to sandbag him, reshooting Welles’s ending to make it happier and removing about 40 minutes of material.

But I doubt very highly that the man who directed the Voodoo Macbeth (or RKO, for that matter) would have allowed any of those 40 minutes to mimic the remarkable racism contained within the novel:

“A cheerful darkey went by the house, loudly and tunelessly whistling some broken thoughts upon women, fried food and gin.”

Can Tarkington’s oddness and precocity before the age of four excuse such an ugly description? Probably not. There are some good reasons why Tarkington’s novels aren’t so easy to find. And in light of the present NewSouth scrubbing of “nigger” from Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, it’s important to remember that there were novelists like Tarkington who were much worse. The above description is hardly the least of Tarkington’s sins. Consider Ambersons‘s many “comedic” moments involving George Minafer’s servants.

George swore, and then swore again at the fat old darkey, Tom, for giggling at his swearing.

“Hoopee!” said old Tom. “Mus’ been some white lady use Mist’ Jawge mighty bad! White lady say, ‘No, suh, I ain’ go’n out ridin’ ‘ith Mist’ Jawge no mo’!’ Mist’ Jawge drive in. ‘Dam de dam worl’! Dam de dam hoss! Dam de dam nigga’! Dam de dam dam!’ Hoopee!”

Elsewhere in the novel, there’s “Old Sam,” who seems to share the same physical qualities and racist stereotyping as Tom. This leads me to wonder if Tarkington was so racist (precocious?) that he couldn’t even remember whether his servant was named Tom or Sam:

Old Sam, shuffling in with the breakfast tray, found the Major in his accustomed easy-chair by the fireplace—and yet even the old darkey could see instantly that the Major was not there.

It appeared that my initial foray into the Modern Library Reading Challenge was off to an inauspicious start. Particularly since none of this racism contributed much to the story.

Yet the novel gripped me. In much the same way that the equally racist D.W. Griffith film, The Birth of a Nation (released three years before the publication of Ambersons), had gripped me. George Amberson Minafer, the rich and spoiled young man foolish and inexperienced enough to believe that his family legacy will live on forever, is entertaining because his despicable nature is so widely tolerated. At the age of nine, Tarkington describes young Minafer as “a princely terror.” At the age of ten, Georgie tells a reverend to “go to hell.” Georgie is part Little Lord Fauntleroy, part Julian English. He’s hardly innocent of such boorish behavior. “Lawyers, bankers, politicians!” Georgie says early in the book, “What do they get out of life. I’d like to know! What do they ever know about real things? Where do they ever get?”

Georgie’s not entirely off-base with this hubris. As we see later in the novel, being on top of the emerging trends (namely the automobile) is the only way to make some serious money. The problem here is that Georgie wishes to assume a privileged life as a yachtsman rather than use his status to innovate or profit. So it’s quite hard for us to elicit much sympathy. Still, part of the novel’s fun comes from trying to understand why George’s douchery would be so wildly tolerated.

And, oh, dearest woman in the world, I know what your son is to you, and it frightens me! Let me explain a little: I don’t think he’ll change — at twenty-one or twenty-two so many things appear solid and permanent and terrible which forty sees are nothing but disappearing miasma. Forty can’t tell twenty about this; that’s the pity of it! Twenty can find out only by getting to be forty. And so we come to this, dear: Will you live your own life your way, or George’s way? I’m going a little further, because it would be fatal not to be wholly frank now. George will act toward you only as your long worship of him, your sacrifices — all the unseen little ones every day since he was born — will make him act. Dear, it breaks my heart for you, but what you have to oppose now is the history of your own selfless and perfect motherhood.

These sentiments (written in a letter) come from Eugene Morgan, the man who is meant to be with George’s mother, Isabel. Isabel feels utterly compelled to mother the hell out of Georgie. And, of course, George is naturally distrustful of Eugene — in part because he’s confused about Eugene’s daughter, Lucy Morgan, whom he doesn’t quite have the stomach to accept. (There are several embarrassing points throughout the book where George is reduced to stuttering. Even George’s proposal is cringe-worthy: “Lucy, I want — I want to ask you. Will you — will you — will you be engaged to me?”) Tarkington is smart enough to give us a few clues about why Isabel is so protective of her son. Back in the day, Isabel had a choice between two husbands: one who accidentally busted up a bass viol (Eugene) and the other who proved too safe and sane (Wilbur). Guess who Isabel married?

Wilbur, the natural bore keen on a very conservative approach to business, ends up kicking the bucket. Small wonder, one presumes, that Isabel ends up hot to trot for Eugene after the mistake has expired.

Is playing it safe the ultimate vice that Tarkington is exploring? In the novel’s first chapter, Tarkington offers a panorama of the manner in which an unnamed town has changed. We learn of vanished customs like “the all-day picnic in the woods” and a remarkable uptick in embroidering. We learn that houses were more commodious yet unpretentious, offering plentiful space and additional purpose for rooms. Much of this is quite interesting. Unfortunately, racism is also an ineluctable part of Tarkington’s vision:

Darkies always prefer to gossip in shouts instead of whispers; and they feel that profanity, unless it be vociferous, is almost worthless….They have passed, those darky hired-men of the Midland town; and the introspective horses they curried and brushed and whacked and amiably cursed — those good old horses switch their tails at flies no more. For all their seeming permanence they might as well have been buffaloes — or the buffalo laprobes that grew bald in patches and used to slide from the careless drivers’ knees and hang unconcerned, half way to the ground.

It’s safe to say that Tarkington, despite his astute eye for progress, wasn’t much of a progressive. This is especially strange, given Amberson‘s astute potshots against backwards thinking:

“I’m not sure he’s wrong about automobiles,” [Eugene] said. “With all their speed forward they may be a step backward in civilization — that is, in spiritual civilization. It may be that they will not add to the beauty of the world, nor to the life of men’s souls. I am not sure. But automobiles have come, and they bring a greater change in our life than most of us expect. They are here, and almost all outward things are going to be different because of what they bring. They are going to alter war, and they are going to alter peace. I think men’s minds are going to be changed in subtle ways because of automobiles; Just how, though, I could hardly guess.”

If Tarkington was so on the money with technological change, why then was he so out to lunch with his racism? A Booth Tarkington fan site, responding to Thomas Mallon’s criticisms in 2004, writes, “Any charge that the Penrod books were actually racist would have to take into account the entire body of Tarkington’s work.”

Fair enough. James Rosenzweig, another literary adventurer reading his way through all the Pulitzer Prize winners, reports that Alice Adams is also racist — using similar stereotypes when writing about a cook and a waitress. And he reports that none of these stereotypes help to elucidate the family’s character. Jonathan Yardley’s introduction to Penrod observes additional stereotypes that are worse than either Ambersons or Alice Adams (“beings in one of those lower stages of evolution” and an orchestra erupting “like the lunatic shriek of a gin-maddened nigger”), and he concludes that “the reader of the early twenty-first century will pull up short at the appearance of offensive material, and some readers — understandably and legitimately — will simply refuse to continue reading.”

I don’t think any of Tarkington’s descriptions were ironic or satirical. A simile connoting a “gin-maddened nigger” is hardly necessary to advance the story. But I cannot deny that, despite my deep disgust at Tarkington’s stereotypes, there were large sections of The Magnificent Ambersons that captured my interest.

When an automobile unsettles the streets, I liked the way that Tarkington used antediluvian language to demonstrate how incongruous and monstrous it appears to George:

It was vaguely like a topless surry, but cumbrous with unwholesome excrescences fore and aft, while underneath were spinning leather belts and something that whirred and howled and seemed to stagger. The ride-stealers made no attempt to fasten their sleds to a contrivance so nonsensical and yet so fearsome. Instead, they gave over their sport and concentrated all their energies in their lungs, so that up and down the street the one cry that shrilled increasingly: “Git a hoss! Git a hoss! Git a hoss! Mister, why don’t you get a hoss?”

What’s interesting here is that Tarkington uses verbs instead of nouns to show us why George can’t quite parse the beastly motorized vehicle before him. The internal rhyme with the adverbs (“vaguely” and “surry,” “street” and “increasingly”) feels as if Tarkington, a man who was involved in theater while at Princeton, is about to confront the modernist revolution of short declarative sentences waiting in the wings.

Yet since we are forced to contend with both Tarkington’s racism and his natural gifts as a novelist, perhaps we have a truer sense of 1918’s ideological incoherence than the weak-kneed politically correct type hoping to scrub out the ugliness. Books like The Magnificent Ambersons are uncomfortable and test the disposition. Would Jonathan Franzen have ended up like this, if he had been born ninety years earlier? Would Franzen (bigshot social novelist of his time) have hated black people as much as Tarkington (bigshot social novelist of his time) did? Perhaps. Perhaps Faulkner’s maxim applies: a writer is congenitally unable to tell the truth and that is why we call what he writes fiction.

Yet since we are forced to contend with both Tarkington’s racism and his natural gifts as a novelist, perhaps we have a truer sense of 1918’s ideological incoherence than the weak-kneed politically correct type hoping to scrub out the ugliness. Books like The Magnificent Ambersons are uncomfortable and test the disposition. Would Jonathan Franzen have ended up like this, if he had been born ninety years earlier? Would Franzen (bigshot social novelist of his time) have hated black people as much as Tarkington (bigshot social novelist of his time) did? Perhaps. Perhaps Faulkner’s maxim applies: a writer is congenitally unable to tell the truth and that is why we call what he writes fiction.

Next up: Donleavy’s The Ginger Man!