“A genre is hardening. It is becoming possible to describe today’s ‘big, ambitious novel.’ Familial resemblances are asserting themselves, and a parent can be named: Dickens.” — James Wood, “Hysterical Realism.”

“A spectre is haunting Europe — the spectre of communism. All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre: Pope and Tsar, Metternich and Guizot, French Radicals and German police-spies.” Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto

Both of these opening sallies conjure the ominous, sharing a rhythmic persuasiveness that holds the reader’s attention hostage. Both too vibrate with the sincerity of deeply held belief. They exemplify what Northrop Frye has defined as High Style: sentences that seem to come from inside ourselves, as though the soul itself were remembering what it had been told so long ago, unmistakably heard in the voice of an individual facing a mob, or some incarnation of the mob spirit.

Both men argue against dehumanization: Marx in commerce; Wood in literature. Here again is Wood, attacking the mob; outing the enemy:

The big contemporary novel is a perpetual motion machine that appears to have been embarrassed into velocity. It seems to want to abolish stillness, as if ashamed of silence. Stories and sub-stories sprout on every page, and these novels continually flourish their glamorous congestion. Inseparable from this culture of permanent storytelling is the pursuit of vitality at all costs. Such recent novels as Rushdie’s The Ground Beneath Her Feet, Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon, DeLillo’s Underworld, David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, and Zadie Smith’s White Teeth overlap rather as the pages of an atlas expire into each other at their edges.

The conventions of realism are not being abolished, he continues, but are exhausted and overworked. “Such diversity! So many stories! So many weird and funky characters! Bright lights are taken as evidence of habitation… props of the imagination, meaning’s toys… The existence of vitality is mistaken for the drama of vitality…Connections are merely conceptual, rather than human. It is all shiny externality, a caricature.”

So smells the skunk Wood loosens upon contemporary (and primarily American) novelists. There’s no mistaking its odor. In his essay, “Anna Karenina and Characterization,” we learn, with equal clarity, what he prefers: Tolstoy’s characters, and the comfort with which they move and live in their own skins. As with Shakespeare, “they feel real to us in part because they feel so real to themselves, take their own universes for granted.” Tolstoy starts with a description of the body which fixes a character’s essence, says Wood, essences that are referred to repeatedly in the novel. Wood uses Tolstoyean characters as yardsticks throughout the rest of his essays to repeatedly beat the Dickens out of novels that lack human detail and dynamism.

Writing about German author Wilhelm Von Polenz, Tolstoy himself suggests that the greatest novelists love their characters and add little details which force readers to pity and love them as well, notwithstanding all their coarseness and cruelty. Chekhov, whose name is also invoked throughout Wood’s oeuvre, is repeatedly praised as an exemplar of such an author, one who resists conclusion, and loves his characters from afar.

Wood tells us with precise, bold, and often unbelievably beautiful artistry exactly what is good, and how and why it’s good. Isaac Babel’s “atomic” prose is unique because of its discontinuities and exaggeration. “If his stories progress sideways, sliding from unconnected sentence to sentence, then the very sentences vault forward within themselves at the same moment.” J.M. Coetzee’s distinguished novels “feed on exclusion; they are intelligently starved. One always feels with this writer a zeal of omission.” “Bellow’s writing reaches for life, for the human gust.” “…it is Bellow’s genius to see the lobsters ‘crowded to the glass’ and their feelers bent by that glass –to see the riot of life in the dead peace of things.” Henry Green’s “fine determination not to prosecute a purpose…creates an exquisitely unpressing art, unlike any other. “

Wood’s essays typically start with pungent, seemingly incontrovertible axioms. “Fury, a novel that exhausts negative superlatives, that is likely to make even its most charitable readers furious, is a flailing apologia.” “Tom Wolfe’s novels are placards of simplicity. His characters are capable of experiencing only one feeling at a time; they are advertisements for the self: Greed! Fear! Hate! Love! Misery!”

Brief plot summaries follow, then close textual reading, reference to a startling breadth of comparable works, insight into specific titles and literature’s larger landscape, and biographical, contextual background detail. The “man” is not separated from the work. Deftly chosen illustrative quotations frequent the page inspiring the reader to run to where they came from.

But it’s not organization that makes these essays so bracing. It’s a wicked combination of unassailable style and blunt, clear judgment; bold aesthetic valuation and invitation to the unknown. Rosso Malpelo represents Giovanni Verga’s greatest tragicomic achievement. The Radetzky March is Joseph Roth’s greatest novel. Too Loud a Solitude is Bohumil Hrabal’s finest book. The best of J.F. Powers’s stories are “surely among the finest written by an American.” There is no academic conditional here, but there is the occasional whiff of pedantry. “Jonathan Franzen’s aesthetic solution to the social novel – the refuge of sentences – is, I think, the right one, or at least one of them, but his reasons for arriving at it are the wrong ones…” If I were Franzen, I wouldn’t be too happy with this treatment.

In his confidence, Wood recalls Edmund Wilson. Both tend to pontificate with an authoritative tone bordering on arrogant. Here’s the latter on G.K. Chesterton, whose writing on Dickens and elsewhere “is always melting away into that pseudo-poetic booziness which verbalizes with large conceptions and ignores the most obtrusive actualities.” In his first collection of essays, The Broken Estate, Wood points out that Thomas Pynchon’s novels have the “agitated density of a prison.” Instead of “agitated density,” Wilson uses “nervous concentration” to describe the vivid colours of Edwin Drood.

which make upon us an impression more disturbing than the dustiness, the weariness, the dreariness, which set the tone for Our Mutual Friend. In this new novel, which is to be his last, Dickens has found a new intensity. The descriptions of Cloisterham are among the best written in all his fiction: they have a nervous concentration and economy – nervous in the old fashioned sense – that produces a rather different effect from anything one remembers in the work of his previous phases.

One could say there is no middle ground with Wood. But that would be wrong. While he lionizes the best — Cervantes, Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy and a handful of little read foreign writers — and crucifies the worst — Salman Rushdie and Tom Wolfe — he shows both sides of his hand to the rest. Bellow is his only contemporary hero. He praises and punishes Zadie Smith, Jonathan Franzen, and J.M Coetzee, and writes endearingly about V.S. Pritchett, and Henry Green, of whom Elizabeth Bowen once said, “his novels reproduce, as few English novels do, the actual sensations of living.” Green himself, quoted in a John Updike introduction to his works, said that his intention was to use noun, verb and adjective “to create ‘life’ which does not eat, procreate or drink, but which can live in people who are alive.” Little wonder Wood is a fan.

What The Irresponsible Self gives us in essay after essay is guidance and sharp opinion. We also get — and this is what ensures that these essays will stay news — a virtually unmatched capacity to employ cage rattling, sentence-stopping metaphor, and antithesis. These dazzling juxtapositions frequently demand a pause to utter the word ‘Wow!’

“Pride, one might say, is the sin of humble people and humility is the punishment for proud people, and each reversal represents a kind of self-punishment.” “The novel [The Radetzky March]’s formal beauty flows from its dynastic current, which irrigates the very structure of the book.” “Atlanta in the 1990s is a forest of typologies, all of them swaying in Wolfe’s gale-force prose.” “The language is oddly thick fingered – from a writer capable of such delicacy – and stubs itself into the vernacular….”

Two words that Wood uses magnificently have stayed with me since reading. I doubt they’ll ever leave. Of a typical Isaac Babel paragraph, “each sentence seems to disavow its role in the ordinary convoy of meaning and narrative, and appears to want to begin the story anew. And “…Svevo essentially garaged his writing for twenty years.”

Occasionally, however, fancy phrase work trips into the too clever. “Mistress Quickly’s irrelevances, like those of her fictional heirs in Chekhov and Joyce, are sad and funny because they have the aspect of remembered detail but the status of forgotten detail.”

Overall, the quantum of considered thought and the unjargoned artistry with which it is expressed, constitute the strength of this essay collection. Its weakness, if there is one, resides in its introduction entitled “Comedy and the Irresponsible Self.” As Elizabeth Bowen once said, too many prefaces to collections make rather transparent attempts to bind. Wood’s thesis is that modern readers no longer laugh cruelly or correctively at fictional characters, but rather empathize with them ‘gloriously,’ exist with them in the same mixed dimension, share their emotions, and laugh with them through tears. Modern fiction creates uncertainty through incomplete knowledge, which prompts the reader to merge with the characters in order to find out why they do the things they do, or how to “read” certain passages.

This is not a new insight. Socrates saw the connection between tragedy and comedy, as did Dostoevsky, Kierkegaard and others. Charles Lamb in the early 19th century, saw laughter as an overflow of sympathy, an amiable feeling of identity with what is disreputably human. In the 20th century, critics have pointed to the inherent absurdity of human existence, namely the irrational, inexplicable, nonsensical , chaotic –the comic. Related to Wood’s incomplete knowledge, critic Wylie Sypher, in an essay written in the 1950s put it this way: “The deepest ‘meanings’ of art therefore arise wherever there is an interplay between patterns of surface-perception and the pressures of depth-perception. Then the stated meanings will fringe off into unstated and unstatable meanings of great power, felt dimly but compellingly. “

Although Wood rides his idea on irresponsibility into many of these essays, it comes up lame. It’s unoriginal, and too weak to bind these essays together retroactively. And if this isn’t bad enough, the examples he uses to illustrate humor just aren’t funny.

Another theme wends its way through the essays quite naturally however, the one labeled Hysterical Realism. Wood hammers the same nail through the whole book, railing against cartoonish, stereotypical characters, and the primacy of information over human emotion. This argument, while better suited to the collection, is itself an old one. E.M. Forster makes it in Aspects of the Novel, “We may hate humanity, but if it is exorcised or even purified the novel wilts, little is left but a bunch of words. And here’s Peter Ackroyd, in The Listener in 1981: “Some of the more recent American novels…seem to me to be hollow, written at a forced pace, preoccupied with literary special effects, and unable to deal with human beings in other than generalized and stereotypical terms…It is too dazzled by such things [contemporary technology] to allow much space in its language for the workings of human agency. It is a language of power, one in which reality is seen as a phenomenon which can be easily manipulated and controlled…American novelists who live within this language, and whose perceptions are determined by it, are uniquely ill-equipped to deal with human motives and responses, and as a result they are also unable to present any convincing account of their own human society.” What does seem fresher, more original, is Wood’s interest in characters who behave consistently, who remain true to themselves, who live and act according to their own rules.

If Wood’s confident tone recalls Edmund Wilson, the cadence of his prose, and to some extent its content, sounds most like Virginia Woolf. Here she is on modernism, and breaking away from the constrictions of providing plot, comedy, tragedy, love interest, an air of probability:

“Life is not a series of gig lamps symmetrically arranged; life is a luminous halo, a semi-transparent envelope surrounding us from the beginning of consciousness to the end. Is it not the task of the novelist to convey this varying, this unknown and uncircumscribed spirit, whatever aberration or complexity it may display, with as little mixture of the alien and external as possible?”

The essays in Wood’s book appeared in slightly different form in several well known literary magazines. Unfortunately, minor changes were made to his famous Hysterical Realism piece. Instead of “When [Zadie] Smith is writing well, she seems capable of a great deal,” Wood changes “a great deal” to the more sycophantic “almost anything.” The same passage illustrating “brilliant free indirect style” is quoted, but a new paragraph is added after it, starting with the phrase “That is a fabulous bit of writing…” Nothing detrimental to his argument. His direct, unfudged criticisms remain. But it’s just a little disappointing to think that adjustments may have been made for personal, rather than hermeneutic reasons.

Edmund Wilson understood why great reviewer critics are so rare: the pay is lousy, the work Sisyphean. It’s difficult to attract talent under these circumstances, which is why Wilson maintained that it might be a profitable idea for some editor to get a really able writer on literature and make it worth his while to do a weekly column. “He should not be expected to cover what is published, but to write each week of a man or a book. This would prove valuable for the magazine and for the literary world in general.” New Yorker editor David Remnick has chosen to take Wilson’s 73-year-old advice by hiring a really able writer, whose work will now be read by more than a million readers per issue. For lovers of the literary this is to be celebrated.

Wood not only writes ebullient, meticulous exegesis, he’s also an accomplished polemicist. One who has dropped a dirty great big conventional human fart atop the heads of some of America’s best loved contemporary novelists. DeLillo, Pynchon, Wolfe, Franzen, Moody, Foster Wallace — they all just sit there, refusing to accept convention, either incapable of doing anything, or too damned lazy to refute what he’s saying. To date, Wood’s criticisms have gone unanswered save for the odd reactionary calls. Wouldn’t it be nice if someone had balls and brains enough to take him on systematically or intelligently?

In The Irresponsible Self, James Wood stakes a position and argues it with serious zeal. He writes with greater humanity, passion and insight than most of the contemporary novelists he is tasked with reviewing. One can’t ask more of a critic. We’ve seen him in action, and we are humbled. His next book, How Fiction Works, will tell us how he does it.

Let us be clear on this. I saw all five Best Picture nominees. And while I liked the other four, it is an outrage that so many thinking people have been duped by Juno. Ellen Page’s snarky one-note performance, originating from the same creative morass that spawned such execrable “wonders” as Napoleon Dynamite, Little Miss Sunshine, and Wes Anderson’s films after The Royal Tenenbaums, is considered multilayered and superlative. Nobody has had the balls to call out Reitman for relying so heavily upon great character actors like Rainn Wilson and Allison Janney to disguise his creative deficiencies. Juno was nothing more than an extended episode of Arrested Development — a dreadful film in which such filmmaking tactics as six consecutive cuts of a van driving in front of a suburban house are considered “clever” and in which Michael Cera has been encouraged to abdicate his talent in favor of being typecast as the nice guy (and he will most certainly be typecast, if he takes another one of these damnable roles).

Let us be clear on this. I saw all five Best Picture nominees. And while I liked the other four, it is an outrage that so many thinking people have been duped by Juno. Ellen Page’s snarky one-note performance, originating from the same creative morass that spawned such execrable “wonders” as Napoleon Dynamite, Little Miss Sunshine, and Wes Anderson’s films after The Royal Tenenbaums, is considered multilayered and superlative. Nobody has had the balls to call out Reitman for relying so heavily upon great character actors like Rainn Wilson and Allison Janney to disguise his creative deficiencies. Juno was nothing more than an extended episode of Arrested Development — a dreadful film in which such filmmaking tactics as six consecutive cuts of a van driving in front of a suburban house are considered “clever” and in which Michael Cera has been encouraged to abdicate his talent in favor of being typecast as the nice guy (and he will most certainly be typecast, if he takes another one of these damnable roles).

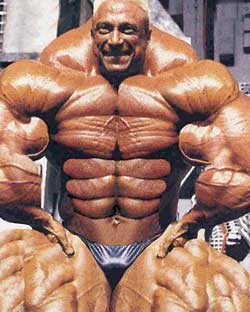

Assael should have devoted more time to original reporting and answering the question of why he sees steroids as America’s True Drug Addiction. In the presence of only anecdotes about users and the absence of a definitive answer to this question, Steroid Nation atrophies into a 300-page summary of doping scandals in sports dating to the 1980s.

Assael should have devoted more time to original reporting and answering the question of why he sees steroids as America’s True Drug Addiction. In the presence of only anecdotes about users and the absence of a definitive answer to this question, Steroid Nation atrophies into a 300-page summary of doping scandals in sports dating to the 1980s.