It is difficult to overstate just how much of an impact Roger Corman had on American culture. But he was a legend and an absolutely vital filmmaking figure. In addition to being a solid genre director (The Intruder, a trenchant examination of political demagoguery written by Charles Beaumont and starring William Shatner and the only movie he lost money on, remains his best film and still packs a wallop today), he had a remarkable knack for spotting talent. He gave James Cameron, Jonathan Demme, Paul Bartel, Joe Dante, Peter Bogdonavich, and Francis Ford Coppola (and so many more) their first shots, often enlisting them to direct their feature film debut. But the deal was that you had to do this with a paucity of money. (In fact, Corman was so cheap that Joe Dante’s The Howling has a funny inside joke in which Corman plays a man in a phone booth scrounging around for change.) This became known as the “Roger Corman film school.” One can see his great influence today in A24 — the fearlessly indie studio that has offered similar opportunities for a new generation of filmmakers.

But Corman was also an instinctive rebel. Behind that irresistible smile and calm voice was a goofball and a natural provocateur. In 2011, much to my amazement, I somehow got the opportunity to speak with Corman in person. While I greatly admired and respected Corman, his eyes beamed with mischief and he made several attempts to stifle laughter as I started asking him provocative questions about certain controversies in his career. He answered all my questions with grace and wit and the two of us got along very well. Partly because he quickly sussed out that I was a fellow rabble-rouser. I’m still amazed at my chutzpah from thirteen years ago, but it did result in a fun and memorable conversation, which I have reposted below. Corman soon followed me on Twitter and he would send me a direct message every now and then, telling me that he had enjoyed an essay I had written. Which was incredibly humbling, surprising, and tremendously kind. Had I somehow passed the Corman test? I guess maybe I did. But I learned later that he did this with a lot of people: those quiet little messages of support. Keep going. Keep making stuff.

That was the way Corman rolled. If he spotted that you had something, he would keep tabs on you. He seemed to detect creative possibilities in the unlikeliest people. He believed so much in the late great character actor Dick Miller that he gave Miller the only lead role in his career with a greatly enjoyable send-up of Beat culture called A Bucket of Blood. In 1967, he leaned in hard on LSD and the hippie movement with The Trip.

You see, Corman had his finger firmly on the pulse of American culture right up until the end of his life. While corporate bean counters looked the other way, Corman leaned in. When I talked with him in 2011, he had not only gone to Zuccotti Park to listen to the brave kids who were camping out for weeks to fight corporate America, but he had also offered a generous donation.

Additionally, Corman set up distribution channels for art house and foreign films through New World Pictures in the 1970s. He would make money with the exploitation pictures and use the profits to ensure that world cinema got its proper due. If it had not been for Corman, Americans may not have been introduced to the likes of Fellini, Bergman, and Kurosawa’s wildest movies. (It was New World that got Kurosawa’s Dersu Uzala into American theatres.)

Rest in power, Roger Corman. You were one of the great ones.

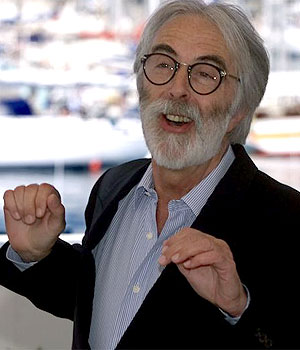

Roger Corman appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #416. In addition to directing some of the most memorable and entertaining drive-in movies of the 20th century (among many other accomplishments), he is most recently the subject of a new documentary called Corman’s World, which is now playing film festivals and is set for release on December 16.

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Not of this earth.

Guest: Roger Corman

Subjects Discussed: Corman’s infamous cost-cutting measures, unusual marriage proposals, bloated corporations, Occupy Wall Street, comparisons between Zuccotti Park and 1960s protests, keeping tabs on pop culture, not giving stars and directors a few bucks to stay around, Easy Rider, the philosophy behind the Corman university, picking people on instinct and the qualities that Corman looks for in a potential talent, Francis Ford Coppola, James Cameron, directors who move up the ladder, The Intruder, why Corman didn’t make explicit socially conscious films after 1962, financing pictures with your own money, the financial risks of being ahead of the curve, looking for subtext in the nurses movies, the sanctimony of Stanley Kramer, Peter Biskind’s “one for me, one for them” idea, simultaneous exploitation and empowerment, the minimum amount of intelligence that an exploitation film has to contain, throwing calculated failures into a production slate, distributing Bergman and Fellini through New World, why Corman believes it was impossible to produce and distribute independent art house movies in the United States in the 1960s and the 1970s, the importance of film subsidies, why Corman gave up directing, Von Richthofen and Brown, the allure of Galway Bay, getting bored while attempting to take time off, the beginnings of New World, the many breasts in Corman’s films, Annabelle Gurwitch’s “Getting in Touch with Your Inner Bimbo,” targeted incidental nudity opportunities, enforcing nudity clauses in contracts, questioning why actresses can’t be sexy without taking their tops off, Rosario Dawson, the undervalued nature of contemporary films, and Corman’s thoughts on how future filmmakers can be successful.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I have to get into your eccentric temperament right from the get-go. There is a moment in this documentary where your wife Julie confesses that you proposed to her. And she said yes. Then you disappeared for a week into the Philippines. And she tried to get in touch with you and finally did get in touch with you and asked, “Well, is the marriage still on?” And you said, “Oh yes, of course.” Your justification was, well, you didn’t want to pay the expense of long-distance telephone. I told this story to my partner and I thought it was amusing. But she was absolutely horrified by this. And this leads me to ask if the notorious reputation you have for aggressive cost-cutting, perhaps one of the finest cost-cutters in the history of cinema — well, how much does this lead into your personal life? And your private life? I mean, surely, when you’re talking about sweethearts and fiancées, you can afford to spend at least a buck or something. I mean, come on!

Corman: Well, that story is possibly true. But the fact of the matter is I’d been in the jungle. At that time, there were no phones. So that was the real reason for the call.

Correspondent: That was the real reason. But this does raise an interesting question. I mean, under what circumstances will you, in fact, pay the regrettable cost of maintaining a relationship like this? Whether it be professional or private.

Corman: Well, I would have to divide that into two answers. Privately, and particularly with my wife and children, I’m much more liberal in spending than I’d ever been on films. On films, I really watch every penny.

Correspondent: Yes. But are there any circumstances you’ve regretted? Either spending extra money or not spending the dollar? Or not spending the dime so to speak?

Corman: I don’t think I regret any overspending. I think, once or twice, I should have let pictures go a little longer and spent a little bit more. These were pictures that were coming in on budget and on schedule. I might have added a couple of extra days to the shooting schedule. But I felt this was a fifteen day schedule. This is the thirteenth day. I have to make a decision. We’re going to shoot it in fifteen days. In retrospect, had I gone to sixteen or seventeen, the additional quality — for lack of a better word — might have been greater than the expenditure.

Correspondent: Well, what’s the cost-benefit analysis for this quality to spending ratio that you’ve devised over the years? Is it largely instinctual? Is it largely looking aggressively at the books? What of this?

Corman: It’s a combination of all of the above, plus just the calculation. I’m always looking for the greatest quality. I’ve done pictures — The Little Shop of Horrors — in two and a half days. I did that with very little money. But I did the best possible job I could do with the amount of money. So I’m looking for the highest possible quality. But since I back my pictures with my own money, which is something you’re never supposed to do, I have to be certain — well, I shouldn’t say certain. I have to have a reasonable guess that I’m going to come out of this one okay.

Correspondent: Do you think that such brutal, Spartan-like tendencies might be applied to, oh say, balancing the federal budget? Or perhaps creating a more efficient Department of Defense? Do you have any ideas on this?

Corman: Well, I believe that it isn’t just the federal government. I believe large corporations or the Department of Defense, which of course is part of the federal budget — I think there’s a certain inherent waste in any large organization, whether it’s public or private. I think they all could be streamlined or — let me put it this way, I think they all should be streamlined. But I question whether it can be done. Because the bureaucracies are in place. And it’s very, very difficult to move.

Correspondent: It’s difficult, I suppose, not just in motion pictures, but for everybody right now. Do you have any thoughts on the present Occupy Wall Street movement that’s been going on in this city while you’ve been here?

Corman: Weirdly enough, I was at the Occupy Wall Street meeting — or sit-in. Whatever you want to call it.

Correspondent: You went to Zuccotti Park?

Corman: Yeah. Just about an hour ago.

Correspondent: Really?

Corman: I donated a little money and they had a couple of pictures taken of me there. Which they said they wanted to use in some way. And I told them I was totally in support of what they’re doing.

Correspondent: I’m surprised you weren’t down there with a movie camera getting master shots for a later production based on Zuccotti Park or something like this. There should be an Occupy Wall Street movie. Is there some possible narrative? Some bucks in this?

Corman: Well, it’s the kind of thing I did before in the 1960s, with the various protest meetings and anti-Vietnam demonstrations. I was there with cameras. And we did use the footage. And this one at the moment isn’t quite that big. If it grows, however, that will be a different thing.

Correspondent: Well, did you see it at Times Square on Saturday? It was actually 15,000 people. And it was pretty aggressive with the cops arresting people. 88 people that day too.

Corman: We came in on Saturday.

Correspondent: Oh, I see.

Corman: And actually I saw opposite ends of New York. I came in, went straight to the opera, went straight from the opera to Comic Con to sign autographs. So I figured if I went from New York to the opera to Comic Con, I saw various aspects of New York.

Correspondent: Well, this leads me to ask you about how you collect your ideas or how you maintain your attentions as to what’s going on in contemporary society. It seems to me that going down to Zuccotti Park, you’re still very much interested in finding out what the present concerns are. I mean, how often do you do this now in your daily life? Just to keep tabs. How do you know, for example, that Hell’s Angels or LSD or Zuccotti Park might be a salable idea?

Corman: These are just aspects of pop culture that come to the surface. And I’ve been involved in all the previous ones. Or most of them, one way or another. And the Occupy Wall Street movement is new. And I went just to see what it was like. And it was strange. There’s a real similarity to the 1960s here. And I don’t know if the young people of today know that what they’re doing, the signs they have, the music they had playing, the discussions — it brought me right back to 1968.

Correspondent: Do you see any differences by chance?

Corman: I saw very little differences. I did notice this. The police were not antagonistic. They were standing there. But I didn’t see any of them make any harmful moves. Where in the ’60s, I did see police make harmful moves. Maybe they’ve learned something over the years.

The Bat Segundo Show #416: Roger Corman (Download MP3)

I don’t think the lackluster business had much to do with Michael Cera. But it’s worth observing that Cera has yet to prop up a phenomenally successful Hollywood movie on his presence alone. He’s found commercial success as a supporting character, although Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist, a $10 million movie that grossed $33.5 million, might qualify as a modest success. But when one considers that Scott Pilgrim‘s budget was closer to $100 million, the decision to use Superbad/Juno momentum as a selling point wasn’t terribly wise. Cera, assuming audiences haven’t tired of him by now, will probably be just fine if he can figure out a way to reinvent his one-note Williamsburg hipster schtick and keep his acting roles confined to second bananas. The man lacks leading man gravitas, and now has the commercial track record to prove it.

I don’t think the lackluster business had much to do with Michael Cera. But it’s worth observing that Cera has yet to prop up a phenomenally successful Hollywood movie on his presence alone. He’s found commercial success as a supporting character, although Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist, a $10 million movie that grossed $33.5 million, might qualify as a modest success. But when one considers that Scott Pilgrim‘s budget was closer to $100 million, the decision to use Superbad/Juno momentum as a selling point wasn’t terribly wise. Cera, assuming audiences haven’t tired of him by now, will probably be just fine if he can figure out a way to reinvent his one-note Williamsburg hipster schtick and keep his acting roles confined to second bananas. The man lacks leading man gravitas, and now has the commercial track record to prove it.

Correspondent: In Funny Games, you have a scenario in which we don’t actually understand the motivations of the two killers. Cache, same thing. The actual motivation behind the videotapes is not entirely spelled out. And, of course, in The White Ribbon, we have a similar situation in which its more about the consequences than it is about the origins. And I’m curious why your films tend to not dwell upon the origins of terrible acts, as opposed to the consequences. Do you think that looking for the root cause of human behavior is a folly? At least with these particular characters in your film?

Correspondent: In Funny Games, you have a scenario in which we don’t actually understand the motivations of the two killers. Cache, same thing. The actual motivation behind the videotapes is not entirely spelled out. And, of course, in The White Ribbon, we have a similar situation in which its more about the consequences than it is about the origins. And I’m curious why your films tend to not dwell upon the origins of terrible acts, as opposed to the consequences. Do you think that looking for the root cause of human behavior is a folly? At least with these particular characters in your film?

Let us first ponder why a reprogramming along these lines is necessary. The film opens with a presidential assassination attempt with an unbelievable paucity of Secret Service agents. Later, there’s a stern judge who announces “Anyone want some tea? It’s from Greece” in his chambers at a wildly inappropriate moment. The newsroom of the fictive Capitol Sun-Times, more All the President’s Men than All the Present Realities, is utterly implausible with newspaper cuts and the Tribune Company’s bankruptcy in recent headlines. Everyone seems to have plenty of time to bullshit around in an editorial meeting. The graceful Angela Bassett almost sells her silly role as a top editor, until she urges Our Intrepid Reporter Based Heavily on Judith Miller (played by Kate Beckinsale) to get some rest, a wildly improbable request when today’s newspapers demand immediate copy to fuel sales. Our Intrepid Reporter lives in a very spacious house with another writer, who has written only one novel. (It’s safe to say that Lurie isn’t familiar with the financial ups and downs that would preclude such an affluent lifestyle.)

Let us first ponder why a reprogramming along these lines is necessary. The film opens with a presidential assassination attempt with an unbelievable paucity of Secret Service agents. Later, there’s a stern judge who announces “Anyone want some tea? It’s from Greece” in his chambers at a wildly inappropriate moment. The newsroom of the fictive Capitol Sun-Times, more All the President’s Men than All the Present Realities, is utterly implausible with newspaper cuts and the Tribune Company’s bankruptcy in recent headlines. Everyone seems to have plenty of time to bullshit around in an editorial meeting. The graceful Angela Bassett almost sells her silly role as a top editor, until she urges Our Intrepid Reporter Based Heavily on Judith Miller (played by Kate Beckinsale) to get some rest, a wildly improbable request when today’s newspapers demand immediate copy to fuel sales. Our Intrepid Reporter lives in a very spacious house with another writer, who has written only one novel. (It’s safe to say that Lurie isn’t familiar with the financial ups and downs that would preclude such an affluent lifestyle.)  Alan Alda, on the other hand, is very good as the attorney who defends Our Intrepid Journalist, even when he’s given a preposterous scenario in which he essentially whines to a judge, “Oh, come on!” That Alda can work these scenarios without diminishing his authority is a credit to his great powers as an actor. Lurie was lucky to get him on board.

Alan Alda, on the other hand, is very good as the attorney who defends Our Intrepid Journalist, even when he’s given a preposterous scenario in which he essentially whines to a judge, “Oh, come on!” That Alda can work these scenarios without diminishing his authority is a credit to his great powers as an actor. Lurie was lucky to get him on board. Let us be clear on this. I saw all five Best Picture nominees. And while I liked the other four, it is an outrage that so many thinking people have been duped by Juno. Ellen Page’s snarky one-note performance, originating from the same creative morass that spawned such execrable “wonders” as Napoleon Dynamite, Little Miss Sunshine, and Wes Anderson’s films after The Royal Tenenbaums, is considered multilayered and superlative. Nobody has had the balls to call out Reitman for relying so heavily upon great character actors like Rainn Wilson and Allison Janney to disguise his creative deficiencies. Juno was nothing more than an extended episode of Arrested Development — a dreadful film in which such filmmaking tactics as six consecutive cuts of a van driving in front of a suburban house are considered “clever” and in which Michael Cera has been encouraged to abdicate his talent in favor of being typecast as the nice guy (and he will most certainly be typecast, if he takes another one of these damnable roles).

Let us be clear on this. I saw all five Best Picture nominees. And while I liked the other four, it is an outrage that so many thinking people have been duped by Juno. Ellen Page’s snarky one-note performance, originating from the same creative morass that spawned such execrable “wonders” as Napoleon Dynamite, Little Miss Sunshine, and Wes Anderson’s films after The Royal Tenenbaums, is considered multilayered and superlative. Nobody has had the balls to call out Reitman for relying so heavily upon great character actors like Rainn Wilson and Allison Janney to disguise his creative deficiencies. Juno was nothing more than an extended episode of Arrested Development — a dreadful film in which such filmmaking tactics as six consecutive cuts of a van driving in front of a suburban house are considered “clever” and in which Michael Cera has been encouraged to abdicate his talent in favor of being typecast as the nice guy (and he will most certainly be typecast, if he takes another one of these damnable roles).