Just under three years ago, I began the Modern Library Reading Challenge. It was an ambitious alternative to a spate of eccentric reading challenges then making the rounds. These included such gallant reading missions as the Chunkster, the Three Card Monte/Three Sisters Bronte, the Read All of Shakespeare While Blindfolded Challenge, and the Solzhenitsyn Russian Roulette Challenge. It took a fairly eccentric person to place the literary embouchure ever so nobly to one’s lips and fire off a fusillade of eupohonic Prince Pless bliss into the trenchant air. But I was game.

Just under three years ago, I began the Modern Library Reading Challenge. It was an ambitious alternative to a spate of eccentric reading challenges then making the rounds. These included such gallant reading missions as the Chunkster, the Three Card Monte/Three Sisters Bronte, the Read All of Shakespeare While Blindfolded Challenge, and the Solzhenitsyn Russian Roulette Challenge. It took a fairly eccentric person to place the literary embouchure ever so nobly to one’s lips and fire off a fusillade of eupohonic Prince Pless bliss into the trenchant air. But I was game.

In my case, the idea was to write at least 1,000 words on each title after reading it. The hope was to fill in significant reading gaps while also cutting an idiosyncratic course across the great works of 20th century literature, with other intrepid readers walking along with me.

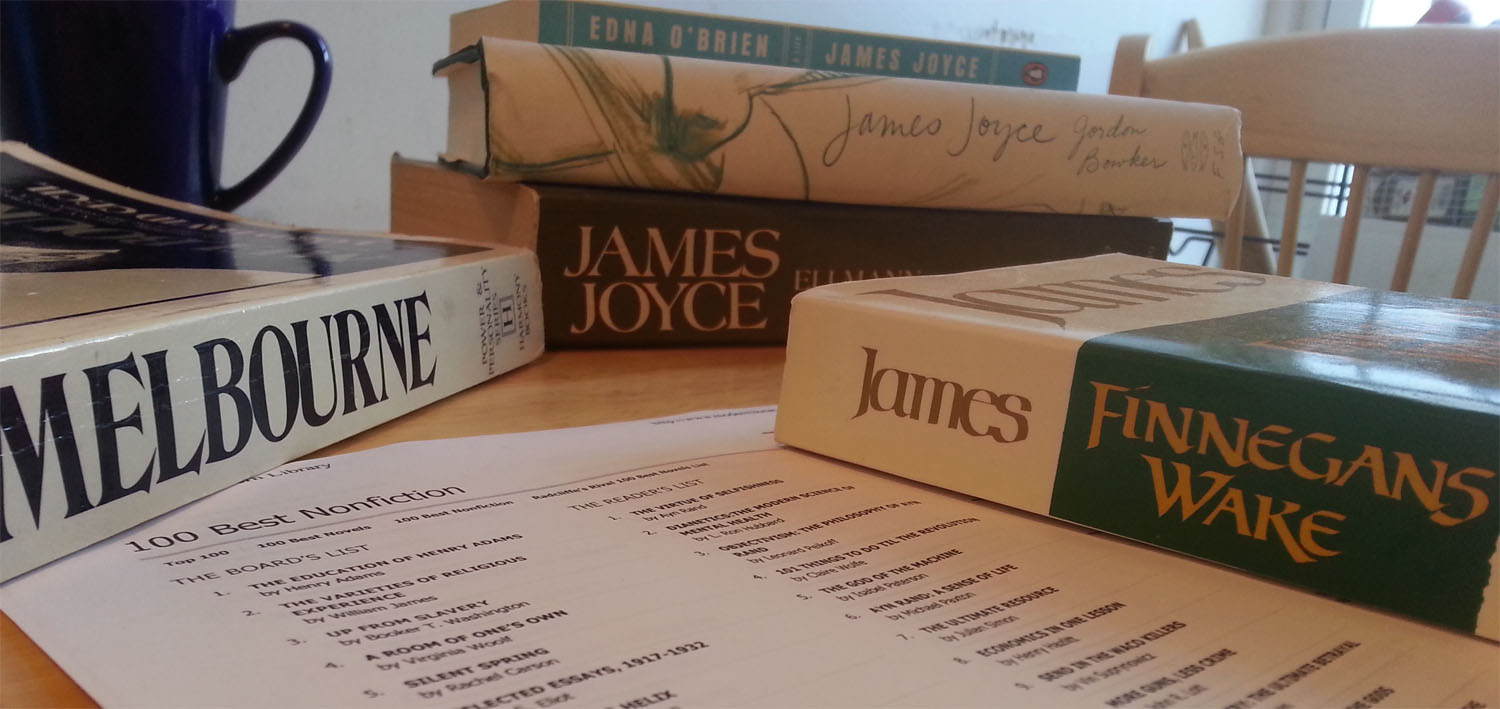

Over the next twenty-three months, I steadily worked my way through twenty-three works of fiction. Some of the books were easy to find. Some required elaborate trips to exotic bookstores in far-off states. When I checked out related critical texts and biographies from the New York Public Library, I was often informed by the good librarians at the Mid-Manhattan branch that I was the first soul to take these tomes home in sixteen years. This surprised me. New York was a city with eight million people. Surely there had to be more curiosity seekers investigating these authors. But I discovered that some of these prominent authors had been severely neglected. When I got to The Old Wives’ Tale, Arnold Bennett was so overlooked that I appeared to be the first person to upload a photo of reasonable resolution (which I had taken from a public domain image published in a biography) onto the Internet.

There were other surprises. I became an Iris Murdoch obsessive. I was finally able to overcome my youthful indiscretions and appreciate The Adventures of Augie March as the masterpiece that it was. My mixed feelings on Brideshead Revisited proved controversial in some circles and caused at least one academic to condemn me. On the other hand, I also sparked an online friendship with Stephen Wood, who was also working his way through the Mighty 100, and was put into contact with an extremely small yet determined group of enthusiasts making similar reading attempts in various corners of the world.

Yet when I told some people about my project, it was considered strange or sinister. When I mentioned the Modern Library Reading Challenge to a much older writer, she was stunned that anyone my age go to the trouble of Lawrence Durrell. (And she liked Durrell!) Her quizzical look led me to wonder if she was going to send me to some shady authority to administer a second opinion.

One of the project’s appeals was its methodical approach: I was determined to read all the books from #100 to #1. This not only provided a healthy discipline, but it ensured that I wouldn’t push the least desired books to the end. Much as life provides you with mostly happy and sometimes unpleasant tasks to fulfill as they arrive, I felt that my reading needed to maintain a similar commitment. This strategy also created a vicarious trajectory for others to follow.

Everything was going well. Very well indeed. Henry Green. Jean Rhys. The pleasant surprise of The Ginger Man. With these authors, how could it not go well? I was poised to read to the finish line. I was zooming my Triumph TR6 down a hilly two-lane highway with a full tank of gas. Cranking loud music. Not a care in the world.

And then I hit Finnegans Wake.

To call Finnegans Wake “difficult” is a woefully insufficient description. This is a book that requires developing an ineluctably Talmudic approach. But I am not easily fazed. Finnegans Wake is truly a book of grand lexical riches, even if I remain permanently stalled within the voluble tendrils of its first 50 pages. I have every intention of making my way through Finnegans Wake. I have reread Dubliners, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and Ulysses. I have consulted numerous reference texts. I have even listened to all 176 episodes of Frank Delaney’s excellent podcast, Re: Joyce. These have all been pleasant experiences, but I am still not sure if any of this significantly contributes to my understanding of Finnegans Wake. However, when you do something difficult, it is often best to remain somewhat clueless. If you become more aware of how “impossible” something may be, then you may not see it through to the end. Joyce remains the Everest of English literature. I am determined to scale the peak, even if I’m not entirely sure how reliable my gear is.

The regrettable Finnegans Wake business has also meant that the Modern Library Reading Challenge has been stuck on pause. It has been eleven months since I published a new Modern Library installment on these pages. And while I have certainly stayed busy during this time (I have made a documentary about Gary Shteyngart’s blurbs, attempted to fund a national walk that I intend to fulfill one day, canceled and brought back The Bat Segundo Show, and created a new thematic radio program, among other industries), I have long felt that persistent progress — that is, an efflorescent commitment to a regular fount of new material — is the best way to stay in shape and keep any project alive.

I have also had a growing desire to read more nonfiction, especially as the world revealed itself to be a truly maddening and perilous place as the reading challenge unfolded. Some have sought to keep their heads planted beneath the ground like quavering ostriches about all this. There are far too many adults I know, now well in their thirties, who remain distressingly committed to the “La la la I can’t hear you!” school of taking in bad news. But I feel that understanding how historical and social cycles (Vico, natch) cause human souls to saunter down dark and treacherous roads also allows us to comprehend certain truths about our present age. To carry on in the world without a sense of history, without even a cursory understanding of ideas and theories that have been attempted or considered before, is to remain a rotten vegetable during the more important moments of life.

It turns out that the Modern Library has another list of one hundred titles devoted to nonfiction. And the nonfiction list is, to my great surprise, more closely aligned to the fiction list than I anticipated.

In 1998, the Washington Post‘s David Streitfeld revealed that the Modern Library fiction list was plagued by modest scandal. The ten august Modern Library board members behind the fiction list had no knowledge over who had voted for what, why the books were ranked the way they were, or how the list had been composed, with many of the rankings more perfunctory than anyone knew. Brave New World, for example, had muscled its way up to #5, but only because many of the judges believed that it needed to be somewhere on the list.

So when the Modern Library gang devoted its attention to a nonfiction list, it was, as Salon‘s Craig Offman reported, determined not to repeat many of the same mistakes. University of Chicago statistics professor Albert Mandansky was signed on to ensure a more dutiful ranking progress. Younger authors and more women were included among the board. Mandansky went to the trouble of creating a computer algorithm so that there could be no ties. But the new iron fist approach offered some drawbacks. There was a new rule that an author could only have one title on the list, which meant that Edmund Wilson’s To the Finland Station didn’t make the cut. And when the top choice was announced — The Education of Henry Adams — the crowd stayed silent. It was rumored that one board member scandalously played with his dentures as the titles were called.

Perhaps the Modern Library’s second great experiment reveals the unavoidable pointlessness behind these lists. As novelist Richard Powers recently observed in a National Book Critics Circle post, “The reading experiences I value most are the ones that shake me out of my easy aesthetic preferences and make the favorites game feel like a talent show in the Iroquois Theater just before the fire. Give me the not-yet likable, the unhousebroken, something that is going to throw my tastes in a tizzy and make my self-protecting Tops of the Pops slink away in shame.”

On the other hand, if it takes anywhere from five to ten years to get through a hundred titles, then the reader is inured to this problem. Today’s favorites may be tomorrow’s dogs, and yesterday’s lackluster choices may be tomorrow’s crown jewels. As the Modern Library reader grows older, there’s nearly a built-in guarantee that these preordained tastes will become passe at some point. (To wit: Lord David Cecil’s Melbourne, the first book I will be reading for this new challenge, is now out of print.)

So I have decided to take up the second challenge, reading the nonfiction list from #100 to #1. Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge titles shall flow from these pages as I slowly make my way through Finnegans Wake during the first challenge. Hopefully, once the disparity between the two challenges has been worked out, I will eventually make steady progress on the fiction and nonfiction fronts. But the nonfiction challenge won’t be a walk in the park either. It has its own Finnegans Wake at #23. I am certain that Principia Mathematica will come close to destroying my brain. But as I said three years ago, I plan to read forever or die trying.

To prevent confusion for longtime readers, the fiction challenge will be separated from the nonfiction challenge by color. Fiction titles shall carry on in red. Nonfiction titles will be in gold.

I’ve started to read Melbourne and I’m hoping to have the first Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge essay up before the end of the month. This page, much like the fiction list, will serve as an index. I will add the links and the dates as I read the books. I hope that these efforts will inspire more readers to take up the challenge. (And if you do end up reading along, don’t be a stranger!)

Now let’s get this party started. Here are the titles:

100. Melbourne, Lord David Cecil (December 27, 2013)

99. Operating Instructions, Anne Lamott (January 14, 2014)

98. The Taming of Chance, Ian Hacking (March 23, 2014)

97. The Journalist and the Murderer, Janet Malcolm (July 17, 2014)

96. In Cold Blood, Truman Capote (November 11, 2015)

95. The Promise of American Life, Herbert Croly (January 21, 2016)

94. The Contours of American History, William Appleman Williams (February 7, 2016)

93. The American Political Tradition, Richard Hofstadter (February 18, 2016)

92. The Power Broker, Robert A. Caro (May 11, 2016)

91. Shadow and Act, Ralph Ellison (November 3, 2016)

90. The Golden Bough, James George Frazer (13 volumes, Third Edition) (November 14, 2016)

89. Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Annie Dillard (November 23, 2016)

88. Six Easy Pieces, Richard P. Feynman (November 30, 2016)

87. A Mathematician’s Apology, G.H. Hardy (December 3, 2016)

86. This Boy’s Life, Tobias Wolff (June 15, 2017)

85. West with the Night, Beryl Markham (August 21, 2017)

84. A Bright Shining Lie, Neil Sheehan (December 6, 2017)

83. Vermeer, Lawrence Gowing (February 22, 2018)

82. The Strange Death of Liberal England, George Dangerfield (September 16, 2018)

81. The Face of Battle, John Keegan (December 26, 2018)

80. Studies in Iconology, Erwin Panofsky (January 23, 2019)

79. The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, Edmund Morris (February 20, 2019)

78. Why We Can’t Wait, Martin Luther King Jr. (February 28, 2019)

77. Battle Cry of Freedom, James M. McPherson (September 11, 2020)

76. The City in History, Lewis Mumford (September 12, 2020)

75. The Great War and Modern Memory, Paul Fussell (March 3, 2022)

74. Florence Nightingale, Cecil Woodham-Smith (June 14, 2022)

73. James Joyce, Richard Ellmann (December 22, 2023)

72. The Gnostic Gospels, Elaine Pagels (March 16, 2024)

71. The Rise of the West, William H. McNeill

70. The Strange Career of Jim Crow, C. Vann Woodward

69. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas S. Kuhn

68. The Gate of Heavenly Peace, Jonathan D. Spence

67. A Preface to Morals, Walter Lippmann

66. Religion and the Rise of Capitalism, R.H. Tawney

65. The Art of Memory, Frances A. Yates

64. The Open Society and Its Enemies, Karl Popper

63. The Sweet Science, A.J. Liebling

62. The House of Morgan, Ron Chernow

61. Cadillac Desert, Marc Reisner

60. In the American Grain, William Carlos Williams

59. Jefferson and His Time, Dumas Malone (6 volumes)

58. Out of Africa, Isak Dinesen

57. The Second World War, Winston Churchill (6 volumes)

56. The Liberal Imagination, Lionel Trilling

55. Darkness Visible, William Styron

54. Working, Studs Terkel

53. Eminent Victorians, Lytton Strachey

52. The Right Stuff, Tom Wolfe

51. The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Alex Haley and Malcolm X

50. Samuel Johnson, Walter Jackson Bate

49. Patriotic Gore, Edmund Wilson

48. The Great Bridge, David McCullough

47. Present at the Creation, Dean Acheson

46. The Affluent Society, John Kenneth Galbraith

45. A Study of History, Arnold J. Toynbee (12 volumes)**

44. Children of Crisis, Robert Coles (5 volumes)

43. The Autobiography of Mark Twain, Mark Twain (3 volumes)

42. Homage to Catalonia, George Orwell

41. Goodbye to All That, Robert Graves

40. Science and Civilization in China, Joseph Needham (5 volumes, abridged)*

39. Autobiographies, W.B. Yeats

38. Black Lamb and Gray Falcon, Rebecca West

37. The Making of the Atomic Bomb, Richard Rhodes

36. The Age of Jackson, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.

35. Ideas and Opinions, Albert Einstein

34. On Growth and Form, D’Arcy Thompson

33. Philosophy and Civilization, John Dewey

32. Principia Ethica, G.E. Moore

31. The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. Du Bois

30. The Making of the English Working Class, E.P. Thompson

29. Art and Illusion, Ernest H. Gombrich

28. A Theory of Justice, John Rawls

27. The Ants, Bert Hoelldobler and Edward O. Wilson

26. The Art of the Soluble, Peter B. Medawar

25. The Mirror and the Lamp, Meyer Howard Abrams

24. The Mismeasure of Man, Stephen Jay Gould

23. Principia Mathematica, Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell (3 volumes)

22. An American Dilemma, Gunnar Myrdal

21. The Elements of Style, William Strunk and E.B. White

20. The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, Gertrude Stein

19. Notes of a Native Son, James Baldwin

18. The Nature and Destiny of Man, Reinhold Niebuhr

17. The Proper Story of Mankind, Isaiah Berlin

16. The Guns of August, Barbara Tuchman

15. The Civil War, Shelby Foote (Three volumes: Fort Sumter to Perryville, Fredericksburg to Meridian, Red River to Appomattox)

14. Aspects of the Novel, E.M. Forster

13. Black Boy, Richard Wright

12. The Frontier in American History, Frederick Jackson Turner

11. The Lives of a Cell, Lewis Thomas

10. The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, John Maynard Keynes

9. The American Language, H.L. Mencken

8. Speak, Memory, Vladimir Nabokov

7. The Double Helix, James D. Watson

6. Selected Essays, 1917-1932, T.S. Eliot

5. Silent Spring, Rachel Carson

4. A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf

3. Up from Slavery, Booker T. Washington

2. The Varieties of Religious Experience, William James

1. The Education of Henry Adams, Henry Adams

* December 15, 2018 Update: While I am striving to read the unabridged versions of all works for this project, upon further reflection, I’ve realized that the cost of obtaining the full 27 volume set of Needham’s opus is well beyond my price range. Each volume ranges from $40 to $200, in part due to the extortionate pricing of Cambridge University Press, a publisher that has proven deaf to my inquiries about obtaining a review copy. This effectively makes this purchase equal to the price of a used car. In addition, it is rather insane for any reader, even one who possesses my ridiculous ambitions, to devote some 8,000 pages to one author. I have reluctantly opted to substitute the five volume Shorter Science and Civilisation in China when I get to this particular essay. As of now, I do have the unabridged The Golden Bough under my belt. And I will spring for the unabridged Toynbee. I hope readers following along can forgive me for cutting corners on one entry. But I do want to complete this project before I depart this earth. And pragmatically speaking, this is the only way to do it.

** August 3, 2022 Update: Four years ago, it was possible to get a copy of the full twelve volume set of Toynbee for under $200. But in a testament to how rapidly these books are going out of print, getting a copy of the full set has become increasingly difficult to find. I may have to tackle the abridged version, with great reluctance.