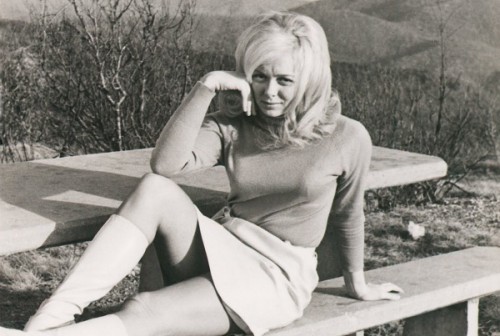

The first thing I was drawn to in Errol Morris’s new movie, Tabloid were Joyce McKinney’s eyes. They darted to and fro, down at her hands, up towards the ceiling, left to right, side to side. But they never faced the camera — or Morris’s Interrotron — directly. Considering that McKinney had quite a story to tell, that of a former beauty queen so enraptured with a Mormon missionary who she flew to London to rescue (or, well, “rescue”) him from that life and convince him through violent means that they must be married, the immediate conclusion on my part was, well, she wasn’t to be trusted. Couldn’t be believed.

That was all well and good, since I knew the bare bones of the Joyce McKinney story. I knew how the FBI’s version contrasted sharply with hers, and how the official — or perhaps “official” — version created a tabloid sensation that, even after almost 35 years, exceeds hyperbole. The UK Fleet Streeters, their dirty laundry credentials aired to full putrid effect throughout the month of July thanks to the never-ending phone-hacking scandal, were well in their element with McKinney, who was arrested and accused of kidnapping her Mormon man Kirk Anderson at gunpoint, squirreling him away to a Yorkshire abode, and raping him repeatedly for three days straight.

But then the camera left McKinney, who is now sixtyish and still a narcissist, to fixate attention on a younger man — raised a Mormon but now removed from the religion — though somehow expert enough to provide color commentary on its supposed cultish activity. And once I realized the younger man, too, did not face the Interrotron and Morris directly, Tabloid lost me. It’s one thing to cast an eye on your supposed subject and make him or her look wholly unreliable. That’s what documentaries do. But when the same techniques for doing so fall down in the face of some outside expert, there’s a serious problem at work.

Unfortunately, once the illusion of narrative coherence broke apart, the reality of how Morris failed in his efforts set in. If tabloid culture and its lurid taste for new content was so important, why did he only speak to two such types? There’s the capable but culpable reporter from The Daily Express, whose claim to fame was being taken in by McKinney’s not-exactly-truthful tale of pious living on the run after she and her accomplice Keith May (who died in 2004) jumped bail and fled London for America. His descendant probably got axed along with News of the World last week. Then there was the more sleazy photographer tasked with finding past dirt on Joyce in the form of bondage photos, among other pictorial delights, his tongue almost involuntarily going to his lips as he recalled the whole exercise.

But what of the larger culture of tabloidism — just eight years removed from Rupert Murdoch’s acquisition of NotW and its sister daily paper The Sun? What prompted the relentless pressure for arid scoops like what McKinney seemed to offer with Sex ‘n Chains? Why were the UK public so riveted by the story? Tabloid certainly wasn’t about to tell us. There was also an easily missed note in the credits that McKinney’s old boyfriend — the not-quite-innocent provider of the photos that splashed across the Mirror‘s pages for days on end — “could not be located.” Well, why not? Based on the scant number of people Morris talked to — at least compared to his earlier, more masterful investigative documentaries — it’s hard to shake the idea he didn’t really try very hard, helped by the fact that many of the other principals were dead (like May) or clearly unavailable (like Anderson).

McKinney may be pathologically self-absorbed, or something more complicated, but Tabloid doesn’t really care about her, other than to subject her to the mockery of the audience. There is little in the way of empathy. Worse, there’s a rather nasty undercurrent of misogyny, aided by the fact that McKinney is the only representative of her sex. That’s a bitter pill to swallow when the current fallen Queen of UK tabloidism is Rebekah Brooks, and when the subject of female-to-male rape has only men to rebut it. I was also discomfited by the notion of all these men ganging up on Joyce in a manner not unlike the fictional Lisbeth Salander, whom Stieg Larsson depicts as the anti-beneficiary of a terrible tabloid campaign. Because hey — to be goth and bisexual and weird is to be splashed across the pages as a triple murder suspect and subjected to a punishing smear campaign that can only be resolved through the cathartic trial that brings the Millennium Trilogy to a close.

McKinney’s catharsis, on the other hand, never really arrived. She found refuge in her home state of North Carolina, still pining — or obsessing — over Kirk, but now so devoted to her dogs that the act of cloning them brought her back into the news cycle in 2008. Tabloid doesn’t really indicate what Joyce McKinney is like now, though it certainly judges her, mocks her, and paints her as a cartoon of ridicule. Morris, I suspect, would say that’s the point. Because tabloids do the same thing. But as we’re all finding out this month, there are limits to what behavior can be tolerated. Even sleaze has a ceiling. All Morris has done by engaging with this in the shoddy manner he has is to reveal uncomfortable truths about himself, most notably that he, too, counts among the man som hattar kvinnor.

Others will likely perceive this film to be mostly about the visuals atop the visuals, the analysis atop the analysis, the meta within the meta. But the real “standard operating procedure” explored in this film isn’t so much the pedestrian issue of how war caused the lines of basic human decency to become fuzzy, but the manner in which a great filmmaker has partially abandoned his subtleties to get Americans hopping mad. The faults lie not in the filmmakers and not, as White suggests, the critics. They’re doing their best to continue the dialogue, but their efforts have increasingly fallen upon deaf ears. For Abu Ghraib does not entertain. And neither does moral outrage.

Others will likely perceive this film to be mostly about the visuals atop the visuals, the analysis atop the analysis, the meta within the meta. But the real “standard operating procedure” explored in this film isn’t so much the pedestrian issue of how war caused the lines of basic human decency to become fuzzy, but the manner in which a great filmmaker has partially abandoned his subtleties to get Americans hopping mad. The faults lie not in the filmmakers and not, as White suggests, the critics. They’re doing their best to continue the dialogue, but their efforts have increasingly fallen upon deaf ears. For Abu Ghraib does not entertain. And neither does moral outrage.