I CAME ALL THIS WAY TO MEET YOU: WRITING MYSELF HOME

by Jami Attenberg

(Ecco, 272 pages)

Jami Attenberg is easily one the most narcissistic and least interesting writers of our time. She literally contributes nothing to literature other than wanton displays of privileged navel-gazing. Should there come a time in which this insufferable solipsist is precluding from publishing any further books, I will write ruthlessly joyful ballads for the many trees that are spared from massacre to spew out her deranged and self-serving lexical offerings. She is truly that awful. There is so much conceited drivel to quote from in her latest book (of which more anon), but I’ll start here:

“I was allowed to stay there for free as long as I walked the dog, an enormous Tibetan mastiff, which I did, diligently, even though the dog didn’t like me all that much and sometimes snapped at me. I felt a little bit like I was the help, there to accomplish a designated task, even though no one actually made me feel that way.”

Maybe because dogs are usually reliable at sniffing out leeches and sponges? The truly atrocious people who boast about their hollow lives and take take take from those who have earned their stature through hardscrabble years of real work? Maybe because even animals have an intuitive sense of sussing out human garbage complaining about being the “help”? (I’ll refrain from the obvious Kathryn Stockett parallel here, but I cannot help but be angered by Attenberg’s casual slide to white privilege as she boasts about traveling to Italy, Sicily, Portugal, England, and Australia without having anything particularly insightful to say. Most of us, of course, simply do our duties and never complain about it. Such are the hard knock realities of living under late-stage capitalism while subtly participating in the “great resignation.”) A few hundred pages later — because self-aggrandizement is the Attenberg formula (and it works! she has the 38,000 followers on Twitter to prove it!) — she trots out her privilege by noting how she and her merry narcissists “leave our towels on the floor for someone to pick up after it is time for us to go.” I’m guessing that this amorphous “someone” is a hell of a lot more interesting than Attenberg. This — combined with Attenberg’s frequent references to being “alone” — is the language of a drug addict and, as Attenberg is so keen to remind us throughout her dreadful dirge, she did drugs, folks! And not only that. She even named one of her chapters after Henry Rollins’s moving memoir. She’s so punk rock! Even when she appropriates from more fascinating and selfless lives for her own gain. Much as she once made a token appearance at Zuccotti Park while the rest of us Occupy Wall Streeters dodged the nets and tear gas from New York’s finest on a daily basis to stand up for the greater good. Because for Attenberg, like many two-bit con artists who confess their shallow “vulnerabilities” on social media in an attempt to win followers and clout, friendships and human relationships are purely transactional:

I knew who my people were, even though I didn’t see them that often anymore. The ones who had stuck by me in my worst moments. The ones I hoped I offered something to in return. Craving collaboration, a shared sense of something bigger than myself, and finding people seeking the same. I had been lucky. I had lost some friends in my life, or sometimes they had lost me. The thing about bad friends is you never realize when you’re being one until it’s too late. Forgiveness and understanding? Regret and apologies? Not in this economy. But I had sustained a life with the ones who counted, the ones I could talk to for hours. The ones I would build something new with every time we met. When I got to meet them.

If you think I have an axe to grind, please know that I do not make these statements lightly. Jami Attenberg is part of a strain of “literary” writers who are destroying our culture with their relentless commitment to unearned amour-propre. I read 162 books last year — many great, some bad, some striated with the usual solipsism that one expects from authors. Such is the price one pays for finding the real truth-tellers, the literary outliers who hold a mirror to our souls and truly humble us with their voices. The writers who remind us why selfless empathy is so important in an age in which caring about other people has become increasingly (and needlessly) politicized. I also had a mother who was a wildly manipulative narcissist, a sister who turned into a cruel and self-serving narcissist who left me for dead and who I will never forgive, and, just last month, ended a relationship with a wildly manipulative narcissist who I had the misfortune to fall for until I cut the cord with great succor from a dear friend (a woman, incidentally; most of my close friends are women). I offer all this not for you to feel sorry for me (that would be an Attenberg move), but to cement that I do know what the hell I’m talking about and I am very much committed to being real. Gratitude, humility, and positivism have been dependable bellwethers in my ongoing quest to be a better person. But these three vital characteristics are clearly beyond a spoiled and wildly overrated braggart like Attenberg, who thrives and subsists because Isaac Fitzgerald (once an inveterate wastrel who was thick as thieves with the abusive Stephen Elliott in his alcohol-smeared Rumpus days, a biographical detail that entailed many years of his life that he, like Attenberg, has nimbly managed to storm past) declared a Dave Eggers-style “No haters” policy when Buzzfeed commissioned this equally shallow opportunist to steer its book coverage, thus securing an agora in which tripe like the below passage is allowed to pass muster without righteous and appropriate pushback:

“Instead, I have become a superior dinner guest. I am wonderful to have at your side while you cook, particularly if you give me a glass of wine, and also to have sit at your table, because I will appreciate your food in a deep, emotional, and highly verbal way, perhaps, in small part, because I did not get to experience that kind of cooking growing up. I’m just always so appreciative of being fed a delicious, home-cooked meal; genuinely, puppy-dog-eyes astonished by the food put before me. Invite me over and feed me. I will be your best companion.”

Puppy dog eyes. Feed this voracious do-nothing dunce, dammit! She’s staring at you!

Sometimes I get so frozen in my feelings, though, or perhaps it is that one feeling is stronger than the others and that’s the one that commands me. I have multiple feelings going on at the same time within me, all day long. This is why I can appreciate a room full of old bones chattering at me silently. This is the makeup of my soul. A room full of bones, a multitude of voices, all at once.

Do you hear that? You’re all nothing more than bones. What a deeply pleasant person!

None of my friends would visit me except if it was my birthday party or the like; there had to be the guarantee of a good time. Williamsburg was too far, it seemed, but from what? The familiar.

Or maybe — and this is easily corroborated by how easy it is to travel out to Williamsburg on the L line — your “friends” just didn’t like you? Speaking as someone who lives off the ass-end of the 2 and 5 lines — a far greater subway crawl than heading to Williamsburg — I’ve never had a problem persuading pals to stop by. Largely because I am fun, giving, firmly committed to secular humanism, genuinely effusive, and I deeply and genuinely care about people. Having visited Attenberg’s loft on Kent Avenue a few times, I can personally attest that every trip felt very much like coercion. A publicist who I will not name once informed me that she “didn’t want to cross Jami.” And this was well before The Middlesteins secured her “literary worth.” Others have reported to me how Attenberg would slice them out of her life if she couldn’t use them. I interviewed this meretricious writer twice back in the days when I had a literary podcast and I only did so because Attenberg — an adept and accomplished narcissist — had a knack for guilting you if you didn’t pay enough attention to her. She preys upon anyone who feels an altruistic instinct to include people. And she had a way of making you feel bad if you declined her invite. Speaking for myself, I deeply regret that I fell for her boorish egotistical act for so long. But being a true-blue empath is often a double-edged sword. And I’ve fallen on my own unscabbered blade far too many times to secure my own obscurity. Perhaps I was just as nonessential as the poor neighbor Attenberg describes in her cluelessly self-absorbed and vile volume. Your apartment floods and here’s that narcissistic writer who only hangs out with you to cadge cigarettes and does fuck all to help you. The next thing you know, you’re dead. “We looked out for each other,” writes Attenberg in a blithe manner that reminded me of Evelyn Waugh at his nastiest, “but sometimes people fall through the cracks.” Written like a true sociopath. A manipulative impostor who also writes pages later, “[I]t helps me to be of service to the universe.” Well, only in the most Brahmin of ways. Then there is risible atonement here:

I don’t regret any of it, except for how much money I spent on drugs. And also, sometimes I was an asshole. And for that: I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry.

You’ve never been sorry at all, Jami Attenberg. You’ve hurt many good people. They’ve told me the details. You’re a terrible person. And no amount of pain that you’ve experienced gives you the excuse to be an asshole.

I am sure the easily triggered peanut gallery, all of them so eager to cavil and find fault with a middle-aged dude taking a necessary stand against an unmitigated narcissist and hubris-fueled mediocrity inexplicably bound in print, will look to my biographical details and my attack dog approach here as evidence of a bias that I may have against narcissistic women. And they may very well be right. But I have also publicly denounced a vast panoply of male narcissists (some of whom have turned out to be abusive) that includes Jonathan Franzen, Jonathan Safran Foer, Jonathan Lethem, almost every writer named John or Jonathan (though Ames and Wray are both good eggs and I will defend both of them to the death), Philip Hensher, Stephen Elliott, Blake Bailey, Dave Eggers, and scores more over the last twenty years. 88% of male cultural critics are narcissists. In my time, I have feuded at some point with nearly all of them. Because I hate narcissists. They are the cockroaches who crawl in your kitchen that you feel an overwhelming desire to crush with a ball-peen hammer. Never mind the damage to the lino and the kitchen island. There’s a greater pestilence to eradicate. A higher duty, so to speak. And any amount of collateral property damage that bites into your security deposit is worth your noble efforts at genocide. Narcissists have lied about me, blatantly mischaracterized who I truly am and attempted to ruin me with bold prevarications on social media, abused me, and hurt me in a myriad of ways. And, as we saw with the last guy who inhabited the Oval Office, narcissists can damage the nation. So when it comes to narcissists, I am an equal opportunity assassin. Let them all be sent to the gallows. They are the true scum of the earth.

But I digress.

“I am interviewing my father because I am trying to figure out why I am the way I am. The daughter of a salesman, now a salesman herself, in a way.”

Let’s talk about Jami Attenberg — an insufferable narcissist for insufferable narcissists. In other words, what now counts as a “writer’s writer” among all these self-absorbed Bookriot-reading dweebs who boast about their galleys on Twitter. An abject salesman. A repugnant and talentless asshat who really wants you to like her! I am sure she is busting out her Hitachi Magical Wand reading my words (that is, if she made it this far). Because Attenberg is one of those shameless schmucks who gets off on her own press. She’s even willing to promulgate a bullshit “ghost story” (the ghost is in the form of a man, of course) because, deep down, she thinks that little of the intelligence of her reading audience.

“Product knowledge is the big thing,” [Attenberg’s father] continues. “That’s what makes a salesperson successful, is that the salesperson can convey the knowledge to the customer. If you feel confident, they will too.”

Attenberg continues to be adulated by fawning and uncritical book nerds across the nation in large part because she has adeptly and indefatigably marketed her public image (a pug-beagle named Sid, constant shoutouts to other writers who are usually as mediocre as she is, relentless invitations to movers and shakers that are more networking opportunities than genuine social bonhomie, et al.). She is, in short, the Establishment. A completely dull and unremarkable figure who makes up for her creative deficiencies and her paucity of invention by “being there” for people in the Jerzy Kosinski sense of the idiom. Because critical thinking continues to be unpracticed in our apocalyptic age, Attenberg can get away with her act. She’s very much like that stiff from accounting who you politely invited for after-work cocktails just to be friendly and who proceeded to monopolize the banter to steal all your work friends and assert dominance.

Well, Saint Jami — who wrote a poorly researched and scantly remembered dud called Saint Mazie — now “fits in.” There is literally nobody left within the Establishment who will call her out for her insipid solipsism and her piss-poor writing. She’s living proof that, if you stick around long enough and canoodle with the right people for years, then your “work” — such as it is — will be unquestionably appraised as divine mantras from the mount. All of these acolytes — which include many authors — follow Saint Jami on any journey she embarks on without question. She has nearly every haughty careerist from John Scalzi to Roxane Gay doing cart wheels on her little finger. Perhaps because these puffed up self-promoters recognize just how effective Saint Jami has been in spinning her dubious stature as “literary novelist.” And perhaps because self-marketing is truly the only cachet that a writer has left in 2022.

“I would make my own advertising. I would be my advertising. I would stop only when they made me. I would keep driving all over America until someone bought my goddamn book.”

I never thought it was possible, but somehow Saint Jami has written a “memoir” that is more ego-driven and insufferable than Norman Mailer’s Advertisements for Myself. You see, these days, it’s privileged women who get to be febrile egomaniacs, not the aging dudebros. Much as it pains me to agree with her, Katie Roiphe did have a point back in 2009 when she pointed to how most contemporary male writers specialized in “an obsessive fascination with trepidation” when it came to spilling the beans about sex. I would suggest further that this trepidation extended to basic truths across the non-carnal spectrum. While this gender role reversal does allow for women to reveal themselves to be just as monstrous as their narcissistic male counterparts, I fundamentally object to the way in which Saint Jami not only sounds like Werner Erhard demanding primal screams for commonplace anxieties from his audience, but how she and her associates package her folderol with an unsophisticated windmill tilt to feminism.

In America, I was just another feminist, and a white, straight, middle-aged one at that. I did not feel radical in America. I felt basic, and when I say “basic,” I mean it in the colloquial sense, as in boring, unoriginal, mainstream. But a thing I have learned, through trial and error, is that my basic feminism can mean different things all over the world. Sometimes it is a helpful conversation to have, and sometimes I’m just being another oppressor, in a way. But in Italy, at that moment, people seemed interested in my feminism. It was a thing to be discussed.

Sure enough, I Came All This Way to Meet You: Writing Myself Home (an unintentionally hilarious title that suggests some Midwestern innocence) is a dripping pile of dewy hubris. A “memoir” that amounts to nothing more than 300 pages of quotidian and unremarkable “struggle” that dares to call itself distinct and that is driven by that most overused word in the English language: I.

“I temped. I filed. I answered phones. I typed up letters, and then I faxed them across town. I pointed people in the right direction. Down the hall. One flight up. You just missed him. I worked in fifty different offices. All these lives. I took food from the conference room without asking. I replaced women on maternity leave. (Never men.) I lent a hand when they were short-staffed. There was a big mailing. Me, alone, in an empty room, stuffing envelopes. Fingers stung with paper cuts at the end of each day. I worked temp-to-perm and was supposed to feel grateful. If you play your cards right, kid. I never made it to perm.”

A brilliant novel published last year — Jakob Guzman’s Abundance — was an emotionally moving and immensely accomplished work of fiction that didn’t make the National Book Award shortlist. Largely because the literary establishment does not like to hear from people who are both poor and not white. They do, however, like to hear from white neoliberal dullards like Jami Attenberg. Nearly every sentence she writes is so hopelessly drenched in the trite bromides of her unremarkable self. And not even in an interesting way like Kate Zambreno or movingly like Leslie Jamison. This is because Attenberg is a solipsistic blowhard masquerading as a sham empath.

There is nothing remarkable in the above passage whatsoever. Millions of Americans live like this. Millions more live much harder lives. Where is the publishing industry when it comes to their stories? In absentia, of course.

“I had jobs where I was taken less seriously or my opinions dismissed entirely for being a woman. I have been told I am difficult. I am difficult in the sense that I am not easy, but fuck easy.”

Or maybe you’re just a self-serving asshole who nobody wants to work with? And being a woman has zero to do with it?

This ridiculous “memoir” — stitched in the formulaic cobweb of the chronic first person and written by a card-carrying sociopath — has been receiving raves from the bourgie lit brigade. (Or at least fellow mediocre “memoirists” like Claire Derderer in the New York Times, who risibly suggests in her review that it is a rare thing indeed when writers blab about their careers. When, in fact, all of us know that writers can almost never shut up about themselves, even when their lives, like Attenberg’s, are duller than an underpaid barista enslaved to humiliating rituals during a pandemic.) Largely because these tasteless boosters do not recognize anyone in this nation that makes less than $50,000/year and they seldom acknowledge the presence of anyone who isn’t Caucasian. Largely because their lives are lies. This vast swath of Biden-voting, risk-averse, toe-the-line privileged scum, who see Saint Jami as their great lord for “suffering” so commonly, have never known real poverty or been homeless or known real struggle. They are, in their own way, as vile in their absence of empathy as Republicans. These unremarkable lemmings would be chewed up in the first ten minutes of the zombie apocalypse. They’re the ones who call an Uber or order regularly from Seamless and never think to tip a Doordash driver more than 10%. Oh, but they relate to this “struggle.” Jami’s “struggle.” And the whole damn book is like this. Hideous narcissism dolled up as feminist empowerment. The solipsistic cry of the privileged white woman. Me me me. Shut the fuck up. It’s disgusting.

As Joyce Carol Oates suggested on Twitter last month, we can accept a narcissistic writer who writes well and who has a distinct command of language. But Saint Jami’s “command” is laden with clunkers:

“I get asked all the time how I can write about such fucked-up families when my mother is so obviously a nice person.” (False humility.)

“I worked for a cable network on websites for critically acclaimed television shows, all of which were created by men.” (Feeble stabs at the patriarchy.)

“but I liked the idea of talking to students as much as I could, and also, I liked the idea of Davenport.” (Endless narcissistic passages that would be roundly condemned on Twitter if the writer in question had a penis.)

“I try to live in hope when I think of America. Things are terrible everywhere, all the time, I know, but let me have my hope anyway.” (Bullshit bromides.)

“I could have a job in an office, a home in the suburbs. (Not that I wanted to live in the suburbs, but still, they existed and seemed safe.) A stable existence instead of fearing for my life, alone on the road.” (Inflated sense of importance, unexamined contradiction of life goals.)

“I looked around for someone to tell, but it was all strangers. On the bus I ended up being wedged between the window and an ophthalmologist who had flown in for a convention in New York. He did not care that I had sold my first book.” (More inflated self-importance.)

“It was the best thing I had ever written, of that I was certain. Still, my publisher dropped me. It didn’t matter that it was good. They were done with me now.” (Yet another inflated sense of self-worth.)

“Peripatetic was a word I learned in my early twenties. I remember looking it up after reading it somewhere and I thought: That sounds familiar.” (Inflated intelligence.)

“I have been to Northern California maybe a dozen times, mostly to San Francisco, back when you could still be a young dirtbag and live there cheaply, when it still seemed a viable, reasonable place to get away for a few days. It was also where I had written my first book, in Napa.” (As someone who lived happily in San Francisco for thirteen years during the last time it was affordable to live there, go fuck yourself. We weren’t dirtbags. We were making things and finding ourselves.)

“At night I ate store-bought fresh pasta, the kind that comes refrigerated and soft and takes three minutes to prepare, and garlic and butter and olive oil and whatever vegetables I could scrounge from the garden near the big house and I would drink two or three (or four) glasses of wine and sometimes I would sob quietly by myself.” (Foodie aspirations drenched in manipulative self-pity.)

“Where were you the first time you learned the word Gorgonzola?” (Oh please.)

“At the edge of the cove, I saw a couple, the man pointing at something, a woman hugging herself to keep warm. I wondered if she wanted to be here. I wondered if she’d had a rough week at work.” (Wild and off-base assumptions about total strangers.)

“People still used digital cameras regularly then to capture moments, instead of phones like we do now. There would be no instant gratification, no immediate upload to the internet. This was just for them, for now.” (Laughable attempts at profundity.)

“There were gunshots all the time out on the streets.” (I honestly don’t know where to start when it comes to Saint Jami’s stabs at streetcred. She tries so hard throughout this book to prove that she’s “punk rock.” But this passage will do.)

“Every museum in Europe has Warhols in its collection—did you know that?” (If Saint Jami were a man, this would be a prime example of mansplaining.)

“Eventually I tired of DC. There was nothing for me there, I decided, a refrain that would become common enough in my life. I walked away so quickly from everything.” (A completely superficial sense of other cities.)

“A great lesson: When someone tells you not to bother dreaming, they’re not on your side.” (Or maybe they’re being kind?)

“The six-packs of yogurt, all different flavors, the fresh-squeezed orange juice, an entire drawer just for cheese. I did not want this life, the husband, the kids. But I did want that refrigerator full of food.” (Pathetic ramshackle gluttony.)

“Rosie brings me lasagna and Julie brings me a tuna casserole, and I have more food than I could ever eat for weeks, and I think: That was my problem in Los Angeles, I didn’t know enough Jews there.” (Gluttony and narcissism walk into a bar. You know the end of the joke.)

“We got drunk very quickly, perhaps she more than me, but I didn’t know her well enough to be able to tell, and then a few of her friends showed up, two men, and we drank a little more, and we decided to drive around town with them. Everyone was kind of a mess except for the driver, who I was trying to flirt with because I was free and in a new city I hadn’t ruined for myself yet.” (More drug addict greed.)

“I am still flattered when people want to be my friend. The chubby child wonders why anyone would want to have her over after school, is grateful to be invited. If someone asks me to meet them for a drink and it feels like something good might come out of it, some sort of future relationship, I enter into it with an open heart.” (Man, I’ve heard this bullshit line from so many narcissists before.)

“I picture her on her barstool now, this writer in Brooklyn. She is slightly older than me, but much better kept. Someone who has been found sexy her entire life. A more accessible type. Taller, more lithe, softer curls on her head, more specific lips, lips with a wry, saucy point of view, pursed, it seems, always.” (Narcissistic jealousy of other peers.)

“Can you imagine viewing everything in your life through two sets of eyes? Yet surely, I have viewed myself through thousands of sets of eyes in my life. Without even knowing it.” (More egregious narcissism.)

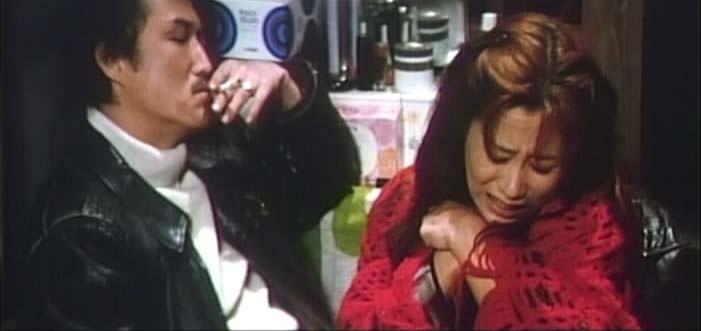

“The main dramatic crisis of the film is her relationship with an angry, aggressive driving instructor who has an unrequited crush on her, and who ultimately is abusive toward her in a confrontation one night. She escapes uninjured, too precious is this character for permanent damage.” (A complete misread of Mike Leigh’s Happy Go Lucky.)

“On my first book tour, sixteen years ago, a male bookstore owner hugged me too long after an event at his shop. ‘I could tell you were special by your picture,’ he said. I wondered if he’d even read my book.” (Narcissistic victimhood by way of wild assumptions.)

“Once I did an event where a man standing in my signing line said to me, ‘You remind me of my daughter; she’s also a narcissist.'” (No examination of this truth. Perhaps it’s too uncomfortable for Saint Jami. But the man in question here was spot-on.)

“I post another picture of myself in a hotel room on Instagram before I leave for the night. This is me, this is where I am, this is what I am wearing. I post it so people can tell me I look OK. I post it so people know I’m alive. I post it as a proof of life. I grow accustomed to seeing myself in a box on my cell phone. Did I live in the box?” (Jesus Christ, do you not listen to yourself, Saint Jami? What remarkable narcissism.)

“What’s it like to wake up every day and not worry what anyone else thinks?” (Saint Jami says this of a man who is not on social media. How can he not know of the “struggle” it is to be judged on social media? Well, maybe if you’re a narcissist, it consumes every hour of your day. But if you’re a well-adjusted human being, who honestly gives a fuck?)

“My boss was tall, a burly Australian man, actually physically intimidating, with a booming voice, and not a day went by that he didn’t comment on my facial expressions as he passed my desk. Particularly if I wasn’t smiling. That loud voice could be heard all across the office. Why aren’t you smiling? What’s wrong? Sometimes tapping his finger on my desk. Why don’t you smile more?” (More cartoonish description to bolster the book’s weak and shaky commitment to “feminism.”)

“At my event I am introduced as living in Brooklyn. From the crowd I hear it. A boo. For being from Brooklyn. I had traveled all that way just to get booed.” (Again, who cares? Maybe if you weren’t so concerned with what other people think and actually listened to them, you might be able to win the crowd over.)

“In 2020, a therapist tells me I’m hardwired for anxiety. I was screwed from the get-go, I think. I’m an excellent compartmentalizer of my feelings. I can organize my thoughts and emotions to protect myself and to build a shield, but that will only take me so far. I say, ‘I have been doing it for years.’ I can tell, she says, with what sounds like sympathy.” (Or maybe the therapist was probably thinking to herself, “Do I tell this solipsitic client that she’s a narcissist? Or do I continue to take her money?”)

“He sold himself to my mother, too.” (Because, as we all know, love is transactional.)

“In his stories, things happened. His characters were physical and often violent. They engaged in sharp dialogue, and they said things they’d regret. They drank a lot.” (Because, of course, every male writer who dips on the dark side of life is clearly a monster. I’m sorry to hear that Attenberg was assaulted. But there’s no need to stack the deck like this.)

“I could always see right through them because I am them: an absolute living nightmare in exactly the same way they are, except slightly more tolerable, because I’m a woman.” (Finally. One slight moment of honesty — near the end of the book. Although let me assure you that Jami Attenberg is more of a “living nightmare” than even she knows.)

“Then I read a status update on Facebook by someone who had been in our writing program, and he mourned him and said, ‘He was the best writer in our class,’ and I wanted to fucking scream, because I was the best writer in our class.” (I don’t think you were. Particularly if this is the way you write as a grown-ass adult.)

What’s particularly calculating about Attenberg describing her assault is that it brilliantly inoculates her from criticism. “Oh, you don’t like my book? Well, clearly, you stand on the side of toxic masculinity!” Hardly. But I have to wonder — in light of Alice Sebold identifying the wrong man who assaulted her — how much of this story was invented or embellished or even fact-checked by the people at Ecco. It’s easy enough to suss out who “Brendan” is. (It took me three minutes to find him on Google.) And since the dude is now dead, we have no way to corroborate the story. We also get a casual detail about a suicide attempt, but no effort by Attenberg to examine what led her to this state. Victimhood has become the currency of “memoirs” of this type. Victimhood is also the very quality that a narcissist flails about to anyone who will listen.

Perhaps the literary sphere is drawn to Attenberg’s work because they too believe themselves to be victims in some way. And when a victim presents herself as largely infallible and as the hero of her own story, you can then wallow in your own collective victimhood and sell multiple copies of your terrible book.