(This is the twenty-sixth entry in The Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge, an ambitious project to read and write about the Modern Library Nonfiction books from #100 to #1. There is also The Modern Library Reading Challenge, a fiction-based counterpart to this list. Previous entry: The Great War and Modern Memory.)

Of the four illustrious figures cannonaded in Eminent Victorians, Florence Nightingale somehow evaded the relentless reports of Lytton Strachey’s hard-hitting flintlocks. Strachey, of course, was constitutionally incapable of entirely refraining from his bloodthirsty barbs, yet even he could not find it within himself to stick his dirk into “the delicate maiden of high degree who threw aside the pleasures of a life of ease to succor the afflicted.” Despite this rare backpedaling from an acerbic male tyrant, Nightingale was belittled, demeaned, and vitiated for many decades by do-nothings who lacked her brash initiative and who were dispossessed of the ability to match her bold moves and her indefatigable logistical acumen, which were likely fueled by undiagnosed bipolar disorder.

Of the four illustrious figures cannonaded in Eminent Victorians, Florence Nightingale somehow evaded the relentless reports of Lytton Strachey’s hard-hitting flintlocks. Strachey, of course, was constitutionally incapable of entirely refraining from his bloodthirsty barbs, yet even he could not find it within himself to stick his dirk into “the delicate maiden of high degree who threw aside the pleasures of a life of ease to succor the afflicted.” Despite this rare backpedaling from an acerbic male tyrant, Nightingale was belittled, demeaned, and vitiated for many decades by do-nothings who lacked her brash initiative and who were dispossessed of the ability to match her bold moves and her indefatigable logistical acumen, which were likely fueled by undiagnosed bipolar disorder.

As someone who has been diagnosed with bipolar, I am inclined to stick up for my fellow aggrieved weirdos. We bipolar types can be quite difficult, but you can’t gainsay our superpowers. A relentlessly productive drive, a magnetism and a magnanimity that bubbles up at our high points, an overwhelming need to help and empathize with others, and a crushing paralysis during depressive spells that often has us fighting the urge to stay in bed. And yet we get up every day anyway, evincing an energy and an eccentric worldview that others sometimes perceive as magical, but that our enemies cherrypick for lulz and fodder — the basis for unfounded character assassin campaigns, if not permanent exile. Hell hath no greater fury than that of aimless and inexplicably heralded mediocrities puffed up on their own prestige and press.

But regular people who aren’t driven by the resentful lilts of petty careerism do get us. And during her life, they got Florence Nightingale. She was flooded with marriage proposals, all of which she rebuffed and not always gently. She was celebrated with great reverence by otherwise foulmouthed soldiers. Yet she also suffered the slings and arrows of bitter schemers who resented her for doing what they could not: obtaining fresh shirts and socks and trays and tables and clocks and soap and any number of now vital items that one can find ubiquitously in any ward, but that were largely invisible in 19th century hospitals and medical military theatres. She had the foresight to study the statistics and the fortitude to work eighteen hour days practicing and demanding reform. And whatever one can say about Nightingale’s mental state, it is nigh impossible to strike at Florence Nightingale without coming across as some hot take vagabond cynically cleaving to some bloodless Weltanschauung that swiftly reveals the superficial mercenary mask of a boorish bargain hunter.

Florence Nightingale nobly and selflessly turned her back from the purse strings of privilege, hearing voices caracoling within her head that urged her to do more. While she was not the only nurse who believed in going to the front lines to improve conditions (the greatly overlooked Mary Seacole, recently portrayed by the wildly gifted and underrated Tina Fabrique in a play, also went to Crimea), it is now pretty much beyond question that she revolutionized nursing and military medicine through her uncommon will and a duty to others in which she sacrificed her own needs (and caused a few early suitors to suffer broken hearts). That she was able to do all this while battling her own demons is a testament to her redoubtable strength. That her allies returned to her, determined to see the best in her even after she was vituperative and difficult, is a tribute to one of humanity’s noblest qualities: putting your ego aside for the greater good.

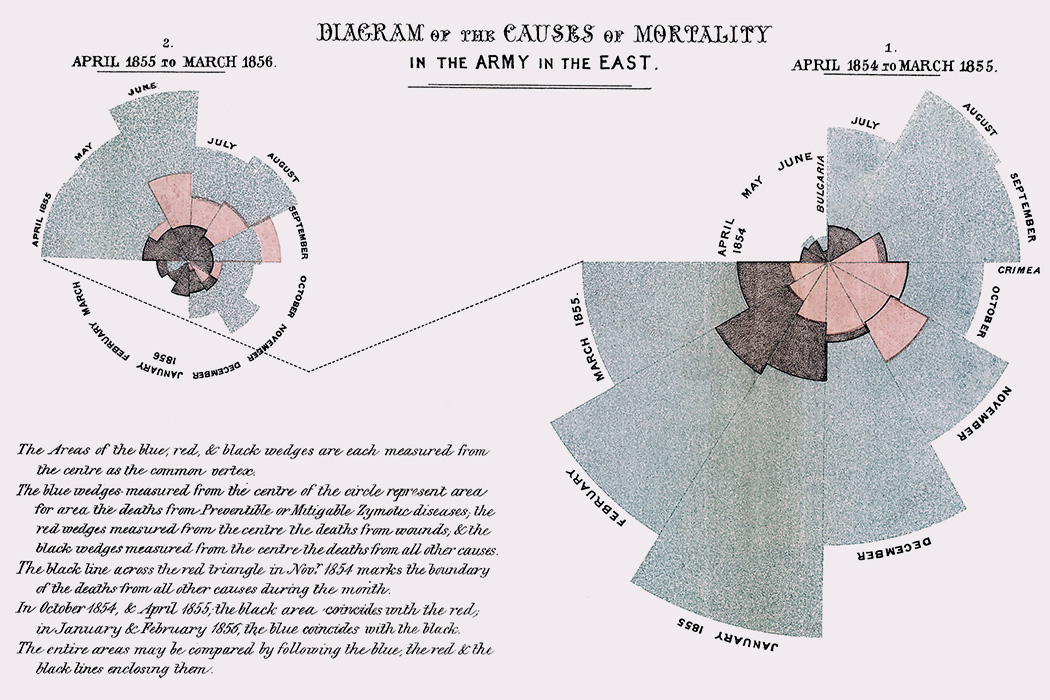

A century before PowerPoint turned 90% of all meetings into meaningless displays of vacuous egotism, Florence Nightingale was quite possibly the first person to use colorful graphical data at great financial expense (see above — it’s beautiful, ain’t it?) to persuade complacent men in power to care for overlooked underlings wounded in war and dying of septic complications in overcrowded and unhygienic hospitals. She was savvy and charismatic enough to win the advocacy of Lord Sidney Herbert, who, despite being a Conservative MP, had the generosity and the foresight to understand the urgent need for Nightingale’s call for revolution. Herbert secured funds. The two became close confidants. Yet poor Herbert suffered a significant erosion in his health and died at the age of fifty because he could not keep up with Nightingale’s demands.

I suspect that men in power resented such noble sacrifices, which could account for why Nightingale was often portrayed as a freak and a deranged outlier in the years immediately following her death. But biographer Cecil Woodham-Smith saw a different and far more complex woman than the haters. Her terrific and mesmerizing and well-researched 1950 biography on Nightingale greatly helped to turn the tide against one of the most astonishing and inspiring women that medicine has ever known. And Woodham-Smith did so not through preordained hagiography, but by taking the time to carefully and properly sift through her papers (and even a well-preserved lock of her bright chestnut hair, still as robust and as lambent as the lamp Nightingale carried in the dark more than a century later). There is a vital lesson here for today’s social media castigators, especially the testosterone-charged troglodytes who casually smear women, that they will likely ignore.

.

Next Up: Richard Ellmann’s James Joyce!

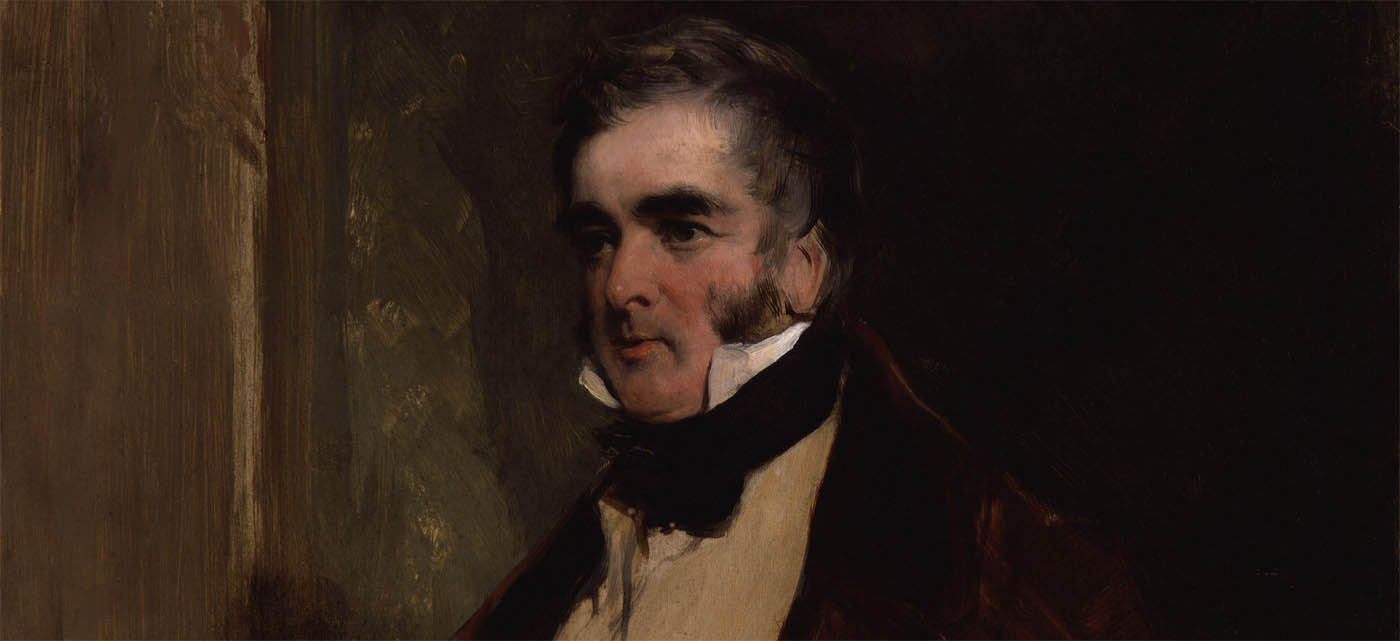

History has produced such a rich pile of devious political figures who spend every spare minute scheming and plotting their rise that today’s aspiring aristocrats, who can be found working every connection to get their kids into bright educational citadels and reliable sinecures, cannot come close to such cutthroat monomania. Yet there are also those who blunder into top office like bumpkins crashing high-class weddings through the simple repetitive act of placing one foot in front the other. William Lamb, aka Lord Melbourne, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom for eight years (1834, 1835-1841) and the subject of Lord David Cecil’s generous biography, was one such man.

History has produced such a rich pile of devious political figures who spend every spare minute scheming and plotting their rise that today’s aspiring aristocrats, who can be found working every connection to get their kids into bright educational citadels and reliable sinecures, cannot come close to such cutthroat monomania. Yet there are also those who blunder into top office like bumpkins crashing high-class weddings through the simple repetitive act of placing one foot in front the other. William Lamb, aka Lord Melbourne, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom for eight years (1834, 1835-1841) and the subject of Lord David Cecil’s generous biography, was one such man.