(This is the twenty-fifth entry in The Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge, an ambitious project to read and write about the Modern Library Nonfiction books from #100 to #1. There is also The Modern Library Reading Challenge, a fiction-based counterpart to this list. Previous entry: The City in History.)

The men went to war. Their psyches were scarred and sotted by the sights and sounds of death and dreary dissolution — all doled out at a hellish and unprecedented new normal. Machine guns, mustard gas, the ear-piercing shrieks of shrapnel and shells, rats gnawing on nearby corpses. The lush fields of France anfracted into a dark flat wasteland.

The men went to war. Their psyches were scarred and sotted by the sights and sounds of death and dreary dissolution — all doled out at a hellish and unprecedented new normal. Machine guns, mustard gas, the ear-piercing shrieks of shrapnel and shells, rats gnawing on nearby corpses. The lush fields of France anfracted into a dark flat wasteland.

The war was only supposed to last a few months, but it went on for more than four years. Twenty-two million lost their lives in the First World War. Many millions more — the ones who were lucky to live — were shattered by the experience. Their bodies were bent and their souls were broken. As Richard Aldington observed in his bleak comic novel, Death of a Hero, the trauma that the soldiers carried home became all too common, unworthy of commiseration and often received with scorn.

But, despite the scars and notwithstanding the cruel homeland rebuke, these men somehow sustained a culture during hard-won moments when they weren’t fighting in the trenches and when they weren’t watching their close friends mowed down by the newer and deadlier weapons. Their noble commitment, their fervent faith in some lambent hope plucked from the maws of a mottled landscape, forever changed the way we saw, heard, and expressed ourselves. As Paul Fussell nimbly argues in The Great War and Modern Memory, we are indebted to these soldiers in ways that most people today cannot appreciate.

While The Great War and Modern Memory doesn’t contain the intoxicating sweep and ambition of Frazer’s The Golden Bough in identifying the underlying rituals that have come to define the manner in which we reckon with disruptive and often inexplicable quagmires, it is nevertheless a remarkable volume, one quite essential in charting the trajectory of how humans expressed themselves through poetry, letters, fiction, and even postwar mediums. I first read this book in my early twenties — many years before I would stumble onto sound design as a method of communicating feelings often untranslatable through words — and, even then, I was startled by how Fussell identified early phonographic recordings as a liminal theatre sprinkled with sounds of attack. This was evidenced not only in the hit novelty records scooped up by supercilious aristocrats comfortably ensconced in cushy sacrosanct parlors without a care in the world, but further immortalized in such unlikely texts as Anthony Burgess’s underrated dystopian novel, The Wanting Seed.

There are so many bones baked into the silt of the Somme that human remains were still being exhumed in Fussell’s day. Forensic experts have continued to make efforts to identify skulls in more recent years. But beyond all these history-shattering casualties, there were also significantly influential linguistic precedents derived from these disfiguring events. The “us vs. them” vernacular that was to become a regular feature of all subsequent wars began with the Great War’s “we” and the xenophobia that was swiftly ascribed to the other side through epithets like “Boche,” as well as the cartoonish pastiches that no soldier in history has been immune from assigning to a mortal enemy. Germans were depicted as giants, memorialized in Robert Graves’s “David and Goliath.” Blunden’s Undertones of War described German barbed wire with “more barbs in it and foreign-looking.” Whether John Crowe Ransom explicitly derived his notion of the other from Blunden, as Fussell imputes, is anyone’s guess. But Fussell’s confidence and deep dive into phrases and terms of art is strangely persuasive. He has, unlike any other scholar since, made a vigorous and spellbinding examination of how language pertaining to division and the unshakeable sense that the war would go on forever influenced the Modernists (and even the postmodernists) as they rolled out their comparatively more peaceful masterpieces to the literary front lines in the 1920s.

Contrary to the cliches, life on the front wasn’t just about poetry and gardening. There was the unappetizing perdition of stale biscuits and Maconochie stew, a hideous tinned concoction (which at least one YouTuber has attempted to recreate!) involving bully beef that reminded the men of meals tendered to dogs. There were startlingly brave figures like Siegfried Sassoon, who not only took a bold stance against the war, but evoked the sordid memories of the trenches and a forgotten England in his Sherston trilogy (which dropped just as autofiction practiced by the likes of Dorothy Richardson and Proust was being quietly celebrated and, in turn, inspired Pat Barker to write her terrific Regeneration trilogy). The stertorous gunfire on the front was so loud that, as Fussell helpfully notes, even Pynchon was compelled to memorialize the idea of shells being heard hundreds of miles away in Gravity’s Rainbow. There was even a series of Illustrated Michelin Guides to the Battlefields that made the rounds after the Treaty of Versailles. Fussell repeatedly points to maps as shaky palimpsests staggered with thick wavy lines and often wry notations, but the lack of tangible geography had to spill over somewhere. Poetry was fated to account for the ambiguity.

Fussell makes a strong case for a tectonic shift in expression being practiced even before the war began. Indeed, the war gave E.M. Forster’s famous “Only connect” sentiment some completely unanticipated momentum as the landed gentry attempted to reckon with the period between the two world wars. If the Great War had not happened, what would be the trajectory of literature? Fussell doesn’t mention Rebecca West’s 1918 novel, The Return of the Soldier, but this was one of the first Great War novels to explicitly deal with shellshock and one can read this book today as a fascinating glimpse into a period between frivolous prewar innocence and the stark and gravid sentences that were to come with Eliot, Hemingway, Woolf, and Fitzgerald. Fussell suggests that the young Evelyn Waugh was emboldened in his poetic and often brutal satire by much of the lingering language that the war had extracted from the patina of once regular summer comforts. The charred scenery on the front lines caused soldiers and servicemen to look upward into the possibilities contained within the sky — itself a predominant fixation within Ruskin’s Modern Painters — and not only did Waugh mimic this in the opening pages of his later novel, Officers and Gentlemen, but one cannot read John McCrae’s “In Flanders Fields” without being acutely aware of the “sunset glow” or the sky serving as an anchor for the poppies blowing beneath the crosses or the singing larks still “bravely singing” amidst the destruction.

It’s possible that Fussell may not have arrived at his perspicacious observations had he not gone through wartime and its preceding ablutions himself. In his memoir Doing Battle, Fussell notes that he could not have unpacked Wilfred Owen’s veiled sensuality had he not been smitten himself with the looks of boys in his adolescent years. He also writes of identifying strongly with Robert Graves’s sentiment that one could not easily be alone in the thronged throes of battle. In The Great War and Modern Memory, Fussell sought to unpack irony and poetic elegy as it became increasingly expressed during the First World War. He claimed his study to be “an act of implicit autobiography” and “a refraction of current events.” In Fussell’s case, he had sickened of the Vietnam War’s overuse of “body count” and perceived perspicacious parallels between Owen’s “Insensibility,” a poem which suggests that expressing “sufferings” is simply not enough to understand real loss. One must have palpable experience of warfare’s devastation in order to reckon properly with it.

And perhaps The Great War and Modern Memory is more serious than Fussell’s “stunt books” (Class, which The Atlantic‘s Sandra Tsing Loh rightfully described as a “snide, martini-dry American classic,” and Bad) because Fussell could not find it within himself to betray his own personal connection to war.

Even so, Jay Winter, Daniel Swift, and Dan Todman have rightfully censured Fussell for leaving out or even demeaning the contributions of working stiffs. Make no mistake: Paul Fussell is an elitist snob and more than a bit of a sneering egomaniac. To cite but one of countless examples, Fussell overreaches and reveals his true colors when he suggests that all letters home from the soldiers adhered to what he calls “British Phelgm” (“The trick here is to affect to be entirely unflappable; one speaks as if the war were entirely normal and matter-of-fact.”). War censors certainly created a creative smorgasbord of workaround phrases, but, as someone who has reviewed World War I letters for research, this is an unequivocal load of bollocks — as a cursory plunge into the National Archives swiftly reveals. Fussell is much better tracking idioms like “in the pink” and using his mighty forensic chops to expose undeniable lexical influence.

As our present world moves ever closer to a potential third world war — with Ukraine standing in for a “trouble in the Balkans” — The Great War and Modern Memory reminds us that all the trauma on our shoulders — whether endured by soldiers or civilians — is destined to spill somewhere. We may not have five centuries of democracy and peace to give us the cuckoo clock that Orson Welles famously snarked up in The Third Man, but there are certainly plenty of unknown Michelangelos and da Vincis waiting in the wings to make sense of the ordeals of 2022 life. History, to paraphrase Stephen Dedalus’s famous sentiment, is a nightmare from which all of us are trying to awake.

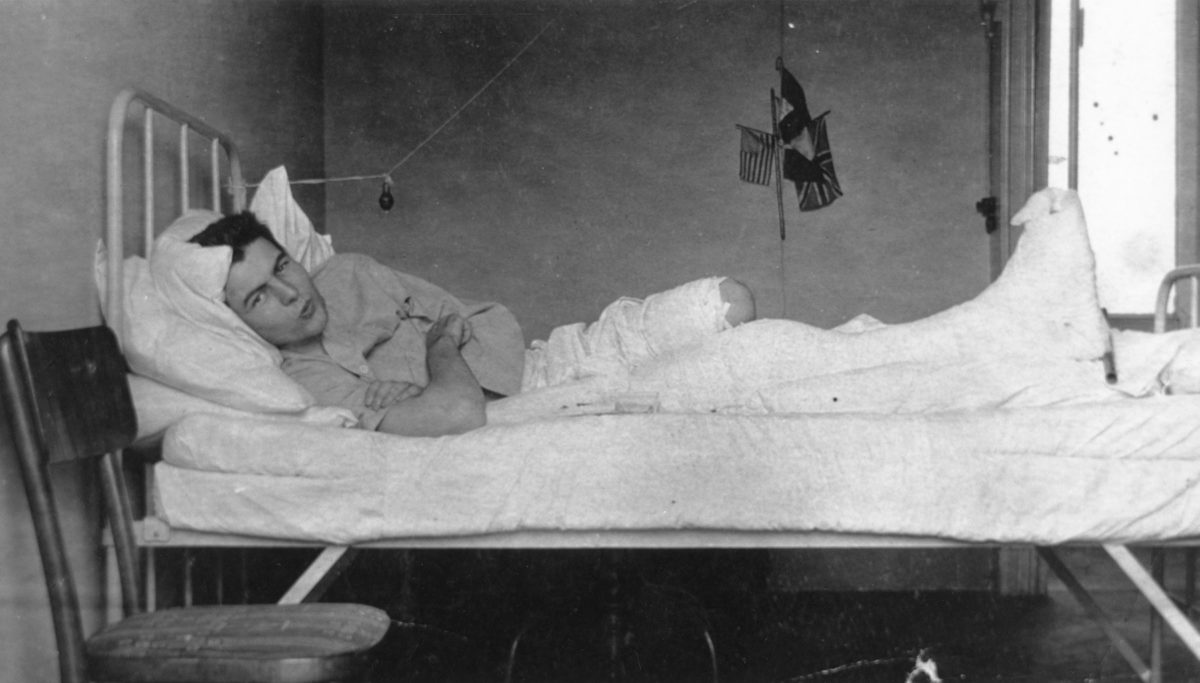

You likely know the basics: An American goes to Italy and enlists as a “tenente.” He drives a battlefield ambulance just before his nation enters World War I. He gets wounded. He meets a nurse at a hospital. He falls in love. He feels free as he recovers. He feels trapped as he returns to the front. He gets disillusioned. He flees. He finds her again. Bad things happen. But A Farewell to Arms is so much more than this. It is a heartbreaking love story. It is a remarkably subtle indictment of war. It shows how people bury their romantic longings behind duty and how there’s a greater bravery in fulfilling what you owe to your heart. It argues for life and love. Its final paragraph is devastating. It zooms along with masterly prose that is buried with treasure. It is one of the greatest novels of the early 20th century. This statement is not hyperbole.

You likely know the basics: An American goes to Italy and enlists as a “tenente.” He drives a battlefield ambulance just before his nation enters World War I. He gets wounded. He meets a nurse at a hospital. He falls in love. He feels free as he recovers. He feels trapped as he returns to the front. He gets disillusioned. He flees. He finds her again. Bad things happen. But A Farewell to Arms is so much more than this. It is a heartbreaking love story. It is a remarkably subtle indictment of war. It shows how people bury their romantic longings behind duty and how there’s a greater bravery in fulfilling what you owe to your heart. It argues for life and love. Its final paragraph is devastating. It zooms along with masterly prose that is buried with treasure. It is one of the greatest novels of the early 20th century. This statement is not hyperbole.