In today’s Chicago Sun-Times, you can find my review of Percival Everett’s I Am Not Sidney Poitier. And it’s rather fitting that much of my review ended up as a list of rhetorical (and possibly unanswerable) questions.

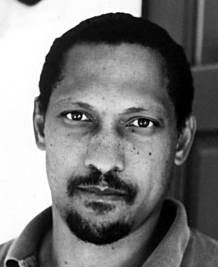

As it so happens, just after filing the review and being wowed by the book, I learned that Everett happened to be in New York. And I was able to set up a rare interview with him (which will be airing as the next episode of The Bat Segundo Show, to be released very soon). Everett, who has avoided nearly every form of marketing for his books*, and who declared to me that he had no interest in the business of publishing or catering to an audience, identified his book as a “novel of ideas.” But I Am Not Sidney Poitier is also steeped in an old-fashioned sense of humor. Here’s a brief excerpt from the forthcoming Segundo installment, in which Everett explains the relationship between these two concepts:

As it so happens, just after filing the review and being wowed by the book, I learned that Everett happened to be in New York. And I was able to set up a rare interview with him (which will be airing as the next episode of The Bat Segundo Show, to be released very soon). Everett, who has avoided nearly every form of marketing for his books*, and who declared to me that he had no interest in the business of publishing or catering to an audience, identified his book as a “novel of ideas.” But I Am Not Sidney Poitier is also steeped in an old-fashioned sense of humor. Here’s a brief excerpt from the forthcoming Segundo installment, in which Everett explains the relationship between these two concepts:

Everett: There are no rules. I don’t believe in any rules when it comes to fiction. If I can make you believe it, then it’s fair game. Probably when I’m working, if I can make myself believe it, then it’s fair game. Because I don’t know what you’re going to believe. And it depends on the work. A novel like Not Sidney, where much of it is more a novel of ideas and the narrator is of a certain sort, can make bizarre perceptions or representations of the world and have the one-dimensional county of Peckerwood County. Whereas in other works, that simply wouldn’t work. So the work talks to me. The most important part of the story is the story. And I can’t impose my feelings or my desire to write a certain kind of thing that day on it.

Correspondent: But in identifying Not Sidney as a novel of ideas, I would argue — and this is where we get into needless taxonomy arguments. But I should point out that you are essentially saying, “Well, this is a novel of ideas.” And maybe the story itself will matter on some basic entertainment level.

Everett: Oh no. The story still matters.

Correspondent: Okay. But I’m curious how committed you are to this idea of the “novel of ideas.” If it’s entirely a construct, should we believe in it entirely or should we believe in the ideas?

Everett: Well, if I’ve done it right, you should believe in it entirely. And superimposed upon this is the narrator’s concept of this being a story of ideas. But you can’t have — and this is not a rule, but, for me, I cannot have a novel where the story is secondary to anything. The world has to exist. And so I have to make it. And I have to make it believable. How I do that can vary and come across in any different number of trajectories or strategies or whatever.

* — This may answer, in part, Gregory Leon Miller’s query this weekend on why Everett’s work hasn’t received the attention it deserves.