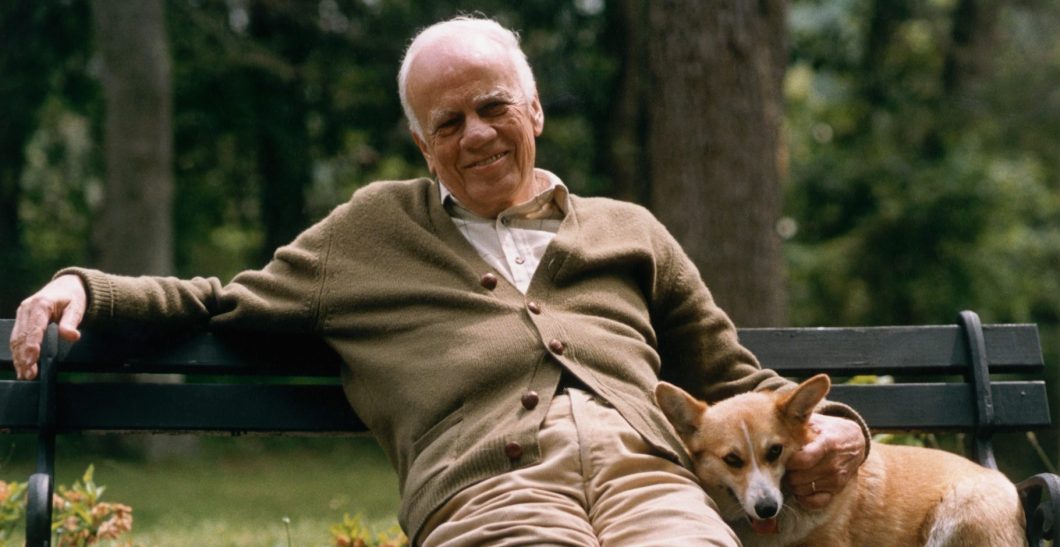

In these years after my illness, when I can no longer speak and am set aside from the daily flow, I live more in my memory and discover that a great many things are safely stored away. It all seems to be in there somewhere. At our fiftieth high school reunion, Pegeen Linn remembered how self-conscious she was when she acted in a high school play and had to kiss a boy on the stage in front of the whole school. She smiled at me. “And that boy was you. You had this monologue and then I had to walk on and kiss you, with everybody watching.” I discovered that this monologue was still there in my memory, untouched. Do you ever have that happen? You find a moment from your past, undisturbed ever since, still vivid, surprising you. In high school I fell under the spell of Thomas Wolfe: “A stone, a leaf, a door. And all of the forgotten faces.” Now I feel all the faces returning to memory.

– Roger Ebert, Life Itself

Roger Ebert was 67 years old when he wrote these words. He was three years away from succumbing to the awful cancer that contorted his body and robbed him of his smart sonorous voice. But what’s so deeply touching about Ebert’s memoir is how you marvel over how the man was still committed to the life of the mind. Garth Greenwell is 46. He is incapable of such reflection or humility. And if his insufferably indulgent third novel, Small Rain, is any indication of his present intelligence and late life wisdom potential, I highly doubt that Greenwell will get anywhere close to Ebert’s poignant well-lived insight in twenty years. If anything, Greenwell seems to be on the Philip Hensher career track to becoming an insufferable Tory, a pretentious cynic whom nobody really likes. Like Hensher, Greenwell is tolerated simply because the son of a bitch has prattled banality for too many years and, instead of recognizing that he has nothing original or interesting or genuinely moving to say, he just doesn’t have the decency to shut the fuck up.

Reading Small Rain is like being trapped in an escape room in which all of the fun puzzles and quirky themes have been removed and you’re left staring at soulless cinderblock walls. You slam your fists against the concrete to the point of bleeding, only to hear Garth Greenwell’s faux patrician voice over the PA system. A copy of Small Rain spits out from a secret slit onto the floor. “We’ll let you out when you finish reading.” “I don’t want to read this shit. Let me out now!” “No, you fucking mook. I am Garth Greenwell, certified literary genius. You cannot leave until you get to the last page. You will genuflect to me and provide me with four pints of your blood and your social security number.” “What’s the alternative?” “You will die in this room.”

And because you value your own life, you slog your way through an interminable and truly awful novel set In Iowa City during the summer of 2020 in which an unnamed poet tears an aorta and ends up in the hospital. And stays in that hospital. With occasional visits from his partner L. And he stays in the hospital. And he stays in the hospital. And does nothing but stay in that hospital without really revealing all that much about himself other than that he is a precious prick who talks about his days teaching in Bulgaria (hey, just like Greenwell himself!) when he’s not mixing up foreign accents (the poet speaks fluent Spanish but he can’t recognize a Colombian accent?) or throwing fits before the nurses.

In fact, Greenwell is so superficial that we learn far more about the house that the poet and L. live in than we do about their relationship. There is a meet-cute flashback in an Iowa City joint, but the only thing we learn about this pair is that the two talked about poetry for two hours and that L. in the initial courtship days didn’t speak English very well (despite being a professor?). And they are big on “alternative nights,” which extends to cooking and speaking in different languages. In other words, we have nothing but vapid shorthand and very little reason to care about this couple because Greenwell serves up nothing but boilerplate. In fact, L. is so underwritten that he is almost as stereotypical as Manuel from Fawlty Towers. But Fawlty Towers, at least, had the benison of being hilarious on multiple viewings. It is believed that Garth Greenwell is so humorless that he has not laughed once since the Clinton Administration.

And the more you learn about the poet — and let’s be clear that there really isn’t all that much to know because Greenwell excels in graphene-flat characterizations, including the Lifetime movie formulaic desperation that kicks in halfway through the novel when we learn that his father abandoned him after learning that he was gay – you really want the fucker to shut up already and die. Greenwell is such a manipulative narcissist that he even throws in some body dysmorphia and sibling bullying near the end of his novel to try guilting us into sympathizing with his bland and unremarkable protagonist. Here is one such banal flashback:

I remembered my mother saying as we drove each weekend to my grandparents’ farm, at each sharp turn she would say it, this is a real death trap. It was part of her constant narration as she drove, as constant as the cassette tapes she pulled out to flip from one side to the other, Juice Newton and Kenny Rogers; still those songs can place me in the car, int eh backseat beside my brother, strapped in:I can conjure up the smell of my mother’s cigarettes, the cheap upholstery, the foam of the headrest my sister, in the front, leaned back against…

Blah blah blah. What on earth is the fucking point of this, Greenwell? Jesus Motherfucking Christ, you’re trolling us, ain’t you, ain’t you, you talentless repetitive mind-numbingly boring fuck?

(menacing crackle from the escape room’s PA system)

“MISTER CHAMPION, I TOLD YOU THAT IF YOU DON’T FINISH THE BOOK, YOU WILL DIE IN THIS ROOM!”

“Alright! Alright! I’m reading it, you sadistic asshole!”

And he stays in the hospital. And he whines. And he stays in the hospital. You read variations on the same tedious descriptions over and over again. You howl at the sick bastard behind the PA system, who responds with frequent laughter. Two gin-scented tears trick down the sides of your nose. But it’s alright, everything is all right, the struggle is finished. You will win the victory over yourself. You love Big Greenwell.

* * *

This is a roundabout way of reporting that Garth Greenwell has used his dubious talents to deliver one of the worst reading experiences I’ve had in the last three years. Garth Greenwell is not about life. He does not care about human beings and is thus, as far as I’m concerned, an enemy to true literature. He writes with the groan-inducing cadences of a long-winded septuagenarian about to show you his vacation slideshow in the basement. You will not find three-dimensional characters in his work. You will find plenty of gay sex (though not so much here) that isn’t nearly as bold or as vivacious or as honest as the carnality flowing throughout Alan Hollinghursts’s rich work. You will also find extremely generalized descriptive shorthand that reveals nothing, along the lines of:

the man, who was young and thin, in his twenties, a short beard visible around his surgical mask, took my arm to examine my IVs.

The man’s physical details, of course, tell us nothing about him and don’t really contribute to the atmosphere. If so, why even bring this up? And Greenwell does it again here:

He was in his midfifties, maybe around L’s age, a white guy, wiry, with a buzz cut under the red ballcap he always wore (a flag on that, too), his sunglasses perched atop the bill.

Not only is Greenwell so without imagination that he gives us a MAGA stereotype, but he even uses the same occluded hair trick for two separate walk-on characters. Or to put it another way, Garth Greenwell can be likened to a bumbling hit man showing up to a far-range job with a .22 Short instead of a sniper rifle.

And when he’s not giving us this woefully inept physicality, he resorts to the same repetitive vomiting:

He was my age, twenty-something, an actor performing in the Festival, not in any glamorous way; he was a local, an extra or maybe something more than an extra.

Garth Greenwell is around my age, actually a little younger but about my age, a writer performing in the Hot Fall Books Olympics with Small Rain, not in any glamorous way, although he does believe he is glamorous, or maybe he is both glamorous and not glamorous like Schrodinger’s cat; I sound so literary when I am pointlessly speculative; he was a yokel from Kentucky, a local from Kentucky, a huckster from Kentucky and now he hates Kentucky, a literary grifter or maybe something more than a literary grifter.

By way of contrast, here is a beautifully compact single-sentence description from Paul G. Tremblay’s excellent The Cabin at the End of the World:

Freckles dust across the bridge of a long nose that dives deeply beneath her large, egg-shaped brown eyes.

Boom! We’re in. We know so much about this woman in only a sentence and we want to know more! Greenwell is completely incapable of such economical descriptive depth.

Oh, and before i am accused of hating literature (I obviously don’t!), let me serve up a counterpoint to further demonstrate Garth Greenwell’s dereliction of descriptive duty. Here’s an excerpt from John Langan’s criminally underrated The Fisherman (Word Horde, you’re doing the Lord’s work!) describing a man who has lost his family in a car accident:

Aside from the scar and the slightly longer hair, the only change I saw in Dan lay in his eyes, which locked into a permanent stare. Not a blank stare, mind. It was a more intense look, the kind that suggests great concentration: the brow lowered ever-so-slightly, the eyes crinkled, as if the starer is trying to see right through what’s in front of them. In that stare, something of the fierceness I’d seen dormant in his face came to the surface, and it could be a tad unsettling to have him focus it on you. Although his manner remained civil — he was always at least polite, frequently pleasant — under that gaze I felt a bit like a prisoner in one of those escape from Alcatraz movies the moment the spotlight catches him.

Unlike Greenwell, one isn’t vexed by the “at least polite, frequently pleasant” aside because there is a natural descriptive escalation in the language. And every physical detail spells out exactly who this guy is. Greenwell can only repeat himself like a lonely parrot braying for a cracker.

* * *

In Small Rain, you will find plentiful prolix descriptions of stuff. Lots of stuff. Not such stuff as dreams are made on, but stuff you can find on any given Target receipt. A little life rounded with a sleep indeed.

But in the public areas there was art on the walls, bright geometric abstractions or gauzy photos of Iowa scenes: an old barn, the sun setting behind it, fields of corn. One showed a stretch of prairie in bloom, though there wasn’t a prairie anymore, not really.

John Cage once suggested that if something was boring for two minutes, then you should sit with it for four. If it was still boring after minutes, try it after eight. Keep multiplying until you get to thirty-two and you eventually discover that something is not boring at all. This hideously generic passage would suggest that Cage’s credo may be one secret ingredient in the Garth Greenwell Writing School. But I’m here to tell you that Greenwell has nothing to say. Zilch! Nada! Nichego! He pads out his endless paragraphs with this nonsense. And then he throws in a half-assed reference to Walter Benjamin after all this. (No, I’m not kidding.)

a shallow wide glass on a long stem that I lifted often in my boredom

Well, you certainly bored the fuck out of me because you couldn’t just write “coupe glass.” But good on you for padding out that word count!

She returned a few minutes later, her hands full of the plastic packaging all of the medical supplies came in, endless boxes and envelopes and bags; so much plastic, I thought, as she sorted them on the counter and began tearing them open, so much waste.

“So much waste.” A rare case of Greenwell having a moment of self-awareness? Somebody hide the lexical firehose from this puffed up practitioner!

The floor in my bedroom had been badly damaged, the beautiful old wooden floors we had salvaged everywhere in the house; here they were strained beyond saving, sanded too often to sand again.

Like sands through the hourglass, so are the duds of his sentences. Why does this unintentionally hilarious stab at “poetry” through mindless repetition remind me of the “life unworthy of life” mantra used to justify the evil Aktion T-4 program? And why does every picture of Garth Greenwell instantly remind me of Reinhard Heydrich? It’s certainly true that I’ve read twenty-five books on the Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany ever since Joe Biden choked in the presidential debate. Still, I can’t shake the obvious metaphor. Reading a Garth Greenwell novel is not unlike a German being forced to vote for Hitler while being observed by an SS officer.

And there’s also the redundant manner in which Greenwell describes the condition of all this stuff. Is he writing fiction or product entries for an L.L. Bean catalog? One reads a prolonged Greenwell sentence beginning with the phrase “But maybe a Snickers bar is a wonderful thing…” and one wonders if whipping up zippy slogans for Madison Avenue is more his speed. He is so condescending to his readership that he seems to believe, at times, that we cannot infer for ourselves whether a pen is uncapped or whether a remote control can turn on a television:

A television hung just to the left of the cabinets, more or less where my bed pointed; I could operate it with a control that hung from a cord attached to the bed.

There was a marker clipped at the top, which she pried loose and uncapped.

It would honestly be more interesting if the doctor aggressively loosened the cap from the clip while pulling it out. But Greenwell appears to have an allergy to active verbs.

* * *

Some of Greenwell’s descriptive redundancies are outright insulting, almost as if Greenwell believes his reader demographic is somewhere between five to eight years old. We are informed — as if we couldn’t figure out the facile arithmetic on our own — that a building that is a “1970s monstrosity” was erected “after the chaos of the sixties.” A building constructed from chaos! Poetry!

There are classist overtones, such as the poet being condescending when he is told that COVID would be “catastrophic” to his medical condition and when he admits that he is attracted to L because his Spanish is “not the language of the streets but a private language.” But it’s an unearned classism. Because Greenwell simply has no concept of how people live and spend money. We are asked to believe, with astonishing incredulity, that L. — a Portuguese professor who is probably making $135k/year tops (that’s what a Glassdoor search gives me) — and the poet narrator — who subsists in the far from lucrative field of freelance writing — can not only pay rent and a mortgage, but can also spend money on credit cards and significant home repairs. (Greenwell does try and cover his ass later by pointing out that the poet is slated to be teaching classes in the fall of 2020, but it’s still unconvincing.) Does the cost of the poet’s healthcare come into play in this novel? Of course not. Clearly, L. is the one pulling the financial weight in this relationship, but it never occurs to Greenwell to investigate how money (particularly when one partner earns much more than the other) can impact a relationship. Instead, L. and the poet simply scream at each other. He may as well be writing an episode of SpongeBob SquarePants. Because this loathsome bastard really does have this annoying tendency to fixate on a word and riff on it in a way that reads like some illiterate yokel trying to mimic Samuel Beckett after skimming the Molloy Trilogy CliffsNotes:

there was a tremendous smile, full voltage, an American smile, a smile of triumph, I thought, a smile of that Midwestern confidence and cheer I found so odious, a pernicious smile, privileged and coddled, a smile that had never known hardship or fear, a smile of utter complacent harmony with its world, a smile I had always hated.

I haven’t quoted the full passage because simply typing it reduces me to a small animal whimpering with hunger for a substantive meal. Greenwell actually believes that if he bombards you with banal repetitive bullshit like this, you will somehow come around and declare him a sui generis prodigy. And judging from the unquestioning reception that his hopelessly desiccated work has received, his marketing strategy seems to have worked.

* * *

I last took a principled swing at this grandiose gasbag back in 2020 — ironically, only weeks before the COVID-19 pandemic — the subject of Small Rain. I received a surprising uptick in emails from some hot literary names who thanked me for writing the piece, but who couldn’t go on the public record because, as one correspondent conveyed to me, “I’ll get into trouble if I cross Garth.” Well, I have no such qualms about getting into “trouble” — in large part because the higher calling of demanding literature that isn’t predicated upon overwrought and superficial bullshit is too vital. I also despise the backscratchers and hobnobbers of the so-called literary world with every fiber of my being. They invented a smorgasbord of untrue rumors about me many years ago after what I had to say about the joys of literature was listened to with more regularity than any of the ponderous logs they dropped into the minuscule ponds of literary rags that nobody reads. One of these opportunistic shit-talkers was, in fact, Garth Greenwell.

To this very day, I simply cannot believe that anybody takes Greenwell’s pompous and atrocious sentences so seriously. Even the grumpy Dwight Garner, who gave Small Rain a pan, professes to be a Greenwell stan. But Garth Greenwell’s “success” — and it is the type of succès fou that only fools in a small circle salivate over — has more to do with Greenwell being a nimble networker rather than a writer of any real talent. He has sycophantic and untrustworthy lapdogs like Matt Bell, Taffy Brodesser-Alzer, and Sam Adler-Bell in his corner to butter his day-old bread, revealing in their undiscerning monomania that propping up mainstream dullards in high places matters more than stumping for the truly original weirdos or having bona-fide principles. But now Garth, dear Garth, Garth is his name, Oh Fucking Humorless Gasbag Garth Please Stop Writing Your Dreadful Fiction, let me forge interminable Garth-like sentences with all the dubious grace of a wino downing five shots in one sitting at a bar because it’s oh so literary, has written a Novel for Our Times! A pandemic novel! The same form that “inspired” Gary Shteyngart to capitulate to egregious navel gazing of the affluent and write his worst novel, Our Country Friends. It is a template that recalls the embarrassing rash of extremely mediocre novels that followed 9/11 more than two decades ago — with only Ken Kalfus and Jess Walter emerging out of this topical Faustian bargain with anything truly original and groundbreaking. I think it says something about our declining literary standards that, outside of Katherine Anne Porter’s moving “Pale Horse, Pale Rider,” you won’t find a lot of fiction about the 1918 Spanish flu that people remember. Previous literary practitioners understood that you could never escape the platitudes and generalizations that froth to the surface when you write about a cataclysmic catastrophe. Risk-averse critics have turned this pigshit into a silk purse because job security matters more than upholding literary standards. Presumably, they also do not want to “cross Garth.”

I have insisted that Garth Greenwell has a small brain and I would like to qualify this.

I am convinced that all the most intelligent artists of Western Europe in recent centuries have been tormented by this search for a justification of their work and a criterion of its value; and that almost all such artists have attempted to solve the problem by some consciously-held idea of art; or in other words that in place of art justified by service to a religion they have sought to evolve an art justified by service to an idea of art itself.

– R. H. Wilenski, The Modern Movement in Art

In Walter Lippmann’s A Preface to Morals (of which I shall later deliver more fulsome thoughts as part of my ongoing Modern Library project), he rightly argues out that art’s purpose is to offer alternative ways of existing and negotiating the universe. Art is a corrective to the moral self-righteousness of religious fundamentalism, which regulates our bodies (and permanently aligns sex with procreation, as decreed by a dubious almighty authority) when it isn’t declaring that all subjects submit with abject fealty to a fictitious deity’s sovereignty. But as religious authority has rightly eroded in the last century, artists have become forced to survive by dint of crass mercantile methods, in which the quest for differing ways of existence is interrupted by the need to paint the wife of a millionaire. It is, of course, the duty of any genuine artist to carry on this vital mission. But Greenwell’s feeble output makes it perfectly clear that he would rather surrender to market forces rather than imbue his characters with anything close to a meaningful consideration of existence. He has successfully manipulated many well-meaning individuals into believing that his mission is that of the holy artist, in large part because he writes about LGBTQIA characters. But if his gay characters are not altogether different from the heinous stereotypes populating a potboiler, then what makes him any different from some garden-variety Brooklyn writer writing another pedestrian debut novel about some twentysomething cipher trying to land a media job or find love?

Greenwell’s small-minded “effort” then is not to burden or challenge us with vital meat-and-potatoes questions, but to force us to submit to badly written and falsely tender longueurs that represent a conformist betrayal of the artistic purpose — in short, a capitulation to capitalism. If Greenwell wanted to write a “topical” novel, why then does he lack the guts to confront the moral fundamentalism of Trumpism? (Since I’ve taken Greenwell to the woodshed, I think it’s only fair to praise him on one minor point. The only page of Small Rain that I appreciated was a moment in which the poet sees how his sister has been brainwashed by right-wing news and is taking the poet’s mother out to a populated restaurant. Had Greenwell written an entire novel with such relatable human stakes like this, I would have written an entirely different essay.) Why does he traffic in such obvious observations such as the way in which physical touch became a rare commodity during lockdown? Well, it’s because he’s little more than a literary hack sitting by the sidelines, a member of the uninvolved who will never take a real risk, an obnoxious milquetoast incapable of putting himself on the front lines.

In fact, the only true sentence in Small Rain — and this one is just as grotesquely belabored as all the others — comes about a third of the way through the book:

It was a mystery, everything around me was a mystery — which is always true, I don’t know how anything works: my computer or a light switch or an airplane or a car, how toilets flush, how electricity is generated or moves from one place to another, it might as well be magic; and now my life depended on it.

Or, to read this more accurately, Garth Greenwell knows fuck all about what it is to be alive. Or if he does know, he’s certainly quite hopeless in conveying this through language! He probably knows deep down — despite his tendency to quote the “germs” line from Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure at nearly every opportunity (he does it again in Small Rain) — that he is a literary charlatan. But he must carry on bombarding us with his hideous prose as if his life depended on it.

In response to being reviewed (naturally, Greenwell the bitchy capitalist pig put his “essay” behind a Substack paywall), Greenwell recently had the wildly arrogant temerity to suggest that “there’s something a little degrading in evaluation.” Mr. Greenwell, the only person who has degraded himself is you. You are the chump who wrote the shitty book: a novel gravid with empty calories that is far from “nourishing” and this is not of any “help in living” whatsoever. Are you truly that delusional? Are you sure you don’t have a cult of acolytes wearing red baseball caps? (Make American Greenwell Again?) And take your lumps like a man. You’re an immensely privileged middle-aged white guy, not a teenager. The degrading thing here would be to accept you as a god who is above reproach. I have already established in two essays (and numerous examples) that you cannot write a smooth sentence even if a terrorist held a gun to your head. You literally have nothing to say about human existence that I haven’t seen more eloquently and originally expressed in the perhaps fifteen thousand books I’ve read over the course of my lifetime.

Of course, if Greenwell does learn how to write a sentence without shoving his Brobdingnagian head up his own asshole, then I will be the first to commend him. But it’s clear that such a day will never arrive. No argument that I promulgate will deter Farrar, Straus & Giroux from continuing to publish further drivel from this wildly arrogant impostor. And all of literature suffers when mediocrity is propped atop the dais.

Correspondent: I wanted to ask you about something that I’ve long been interested in your books, and that is your concern for specific dollar amounts. Again, it plays up here in the Pulaski Diner, where everything is five dollars. And I also think about the scenario with M.R. Chang in Oracle Night, in which there’s the whole situation between the ten dollar notebook and the ten thousand dollar notebook.

Correspondent: I wanted to ask you about something that I’ve long been interested in your books, and that is your concern for specific dollar amounts. Again, it plays up here in the Pulaski Diner, where everything is five dollars. And I also think about the scenario with M.R. Chang in Oracle Night, in which there’s the whole situation between the ten dollar notebook and the ten thousand dollar notebook.