Jeff VanderMeer has had an incredibly toxic and unhealthy obsession with me for nearly twenty years. He has delighted in leading smear campaigns against me — without a shred of evidence — on his blog and on social media. The source of this monomaniacal animus goes back to the fall of 2009. You are about to learn exactly what kind of an abusive and insanely retaliatory maniac Jeff VanderMeer truly is. You are going to learn that, if you cross Jeff, he will declare you an enemy for life and that he will devote any and all resources to impugning you — until either you or him drop dead. And, call me crazy, that ain’t exactly the healthiest relationship you should have with an audience, to say the least. Jeff VanderMeer clearly doesn’t understand that no artist can ever please everyone. But if he shows you exactly how he deals with people who don’t genuflect every ounce of their free will to him, he will be more than happy to weaponize the Internet against them. This is what’s commonly referred to as megalomania. And I think it’s safe to say that Jeff VanderMeer is the Donald Trump of speculative fiction.

Four people have informed me that they have also been recipients of Jeff’s deranged zeal and his private backchannel gaslighting, but, as Jeff has had increased success as a writer (particularly after the Alex Garland film adaptation of Annihilation, which dramatically improved the clunky and poorly written novel), his toxic qualities have only grown worse. His hubris has burgeoned to staggering levels and his talent has atrophied. These four people have feared going on the public record and “crossing” him. And I will protect their privacy. Because I don’t want so see anyone harassed by a pathetic 56-year-old bully.

But I have no such qualms revealing my own dealings with the disordered basket case known as Jeff VanderMeer. (And, believe me, there are far more emails — worse emails — than what I’ve published below.)

I am sick and tired of Jeff VanderMeer constantly manufacturing artificial drama about me. Particularly when I have the receipts about what he did to damage our relationship. I have resisted publishing these emails until now. But I feel that I now have to. Because Jeff VanderMeer is a wanton thug and I don’t want other people to be hit with the same ridiculous abuse. And also because Jeff simply will not stop. And because he will not stop, he has forced my hand. You are going to read the messages of a man who lashed out at me when I was being kind, sensitive, and honest. You are going to see the only writer in 553 episodes who ever felt entitled to another interview on my old literary podcast, The Bat Segundo Show, and who falsely accused me of not being truthful, even though he did not arrange for his books to be sent to me with enough reading time and refused to respect my benevolent honesty.

(I did arrange for another interviewer to interview him. Because that’s the kind of guy I am. I also agreed to hang out with him in a diner when he rolled through New York. And we did — at the Westway Diner on November 21, 2009, according to my records — only for Jeff to spend a lot of his time huffing and puffing in his seat, his arms permanently crossed as if he were stopping himself from punching some perceived enemy, occasionally sneering at me, and interrogating me about my podcast.)

When I gently told him that I was overbooked and that I didn’t have the time to read his books (as I did with every author) and conduct a proper interview, particularly since I had not even been sent copies in time, he threw a stupendous temper tantrum by email and called me a liar. (I forwarded this exchange to a mutual contact, who informed me that Jeff was prone to this sort of volatile communication style. If only I had known earlier, I would never have booked him.) Jeff made a series of increasingly insane accusations against me. Throughout this entire volley, I did my best to play it cool. But Jeff was emailing me four emails for every one I sent, with some new emails contradicting the previous ones.

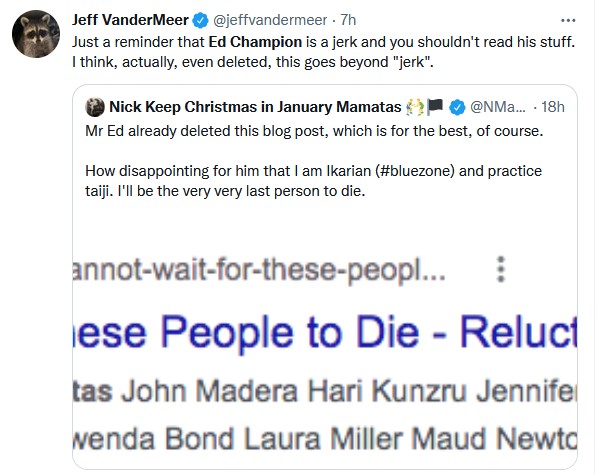

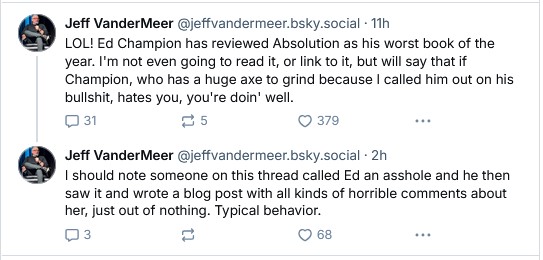

In January 2022, when I was unemployed and had only about fifty dollars to my name, I received a colossal tax bill that I had no way of paying and went on a binge drinking tear. I’m not proud of my slip. I completely lost my cool, to say the least. Jeff VanderMeer seized the moment and intercepted a draft blog post that I had accidentally published and swiftly deleted in my stupid inebriation to whip up a social media campaign against me. I ignored all the vitriol he had spawned and spent my time cleaning up my act. I spent 150 days sober (not so much as a drop of beer or wine), composed a Western soundtrack for a friend’s audio drama, managed to land a job (and some financial help from friends; everyone was paid back within months, including the tax man), and now only drink modestly on the weekends. My only slip from this quasi-sober regimen was shortly after the devastating election results back in November, in which I fell off the wagon and downed a great deal of Black Label. Again, I’m not proud of that. Fortunately, I swiftly course-corrected and was soon sober and writing again and rallying the troops against fascism. (Nobody’s perfect, although Jeff, who will never admit a mistake, will probably tell you that he’s the exception. This is, after all, the way that toxic narcissists roll.)

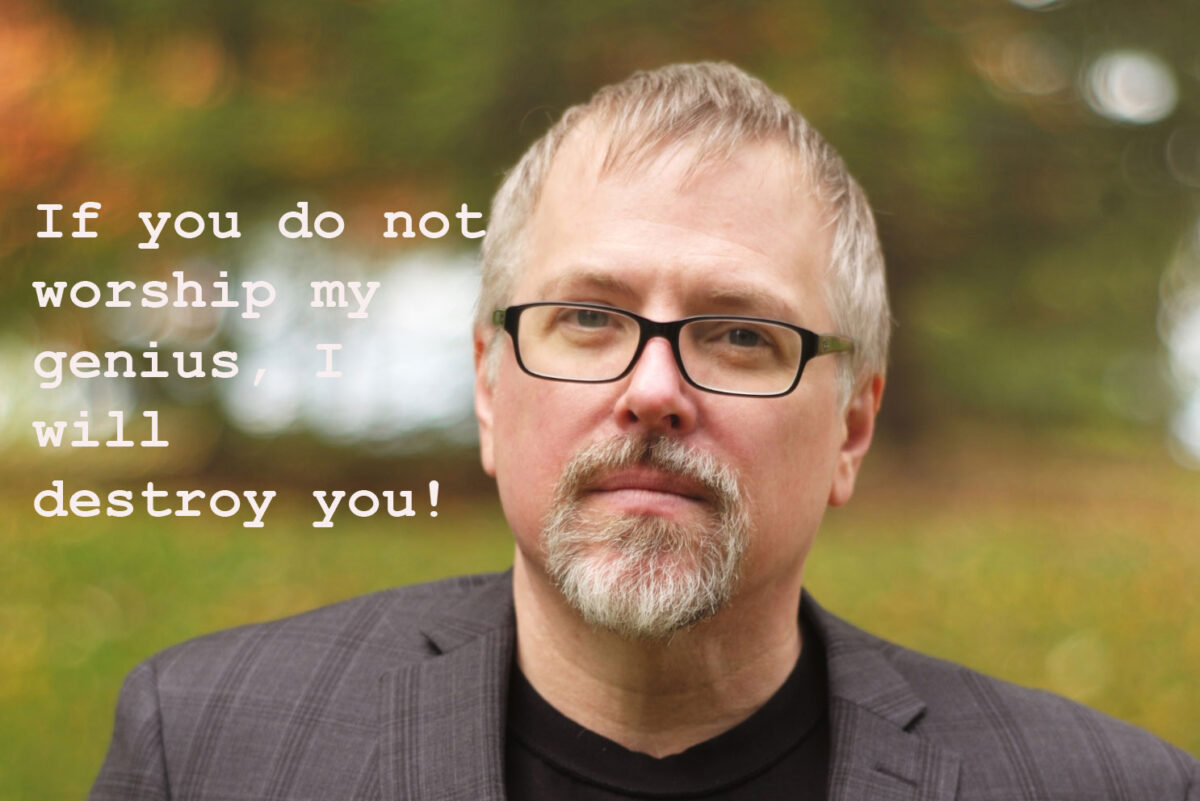

And these circumstances represented the “bullshit” that Jeff was to “call me out” on. Because he really wants everyone — including the barista who undertoasted his bagel; how dare she! — to worship his “genius.” An elitist sociopathic pig like Jeff couldn’t give two shits about anyone who makes under $50,000/year. He is, in short, one of the bad ones.

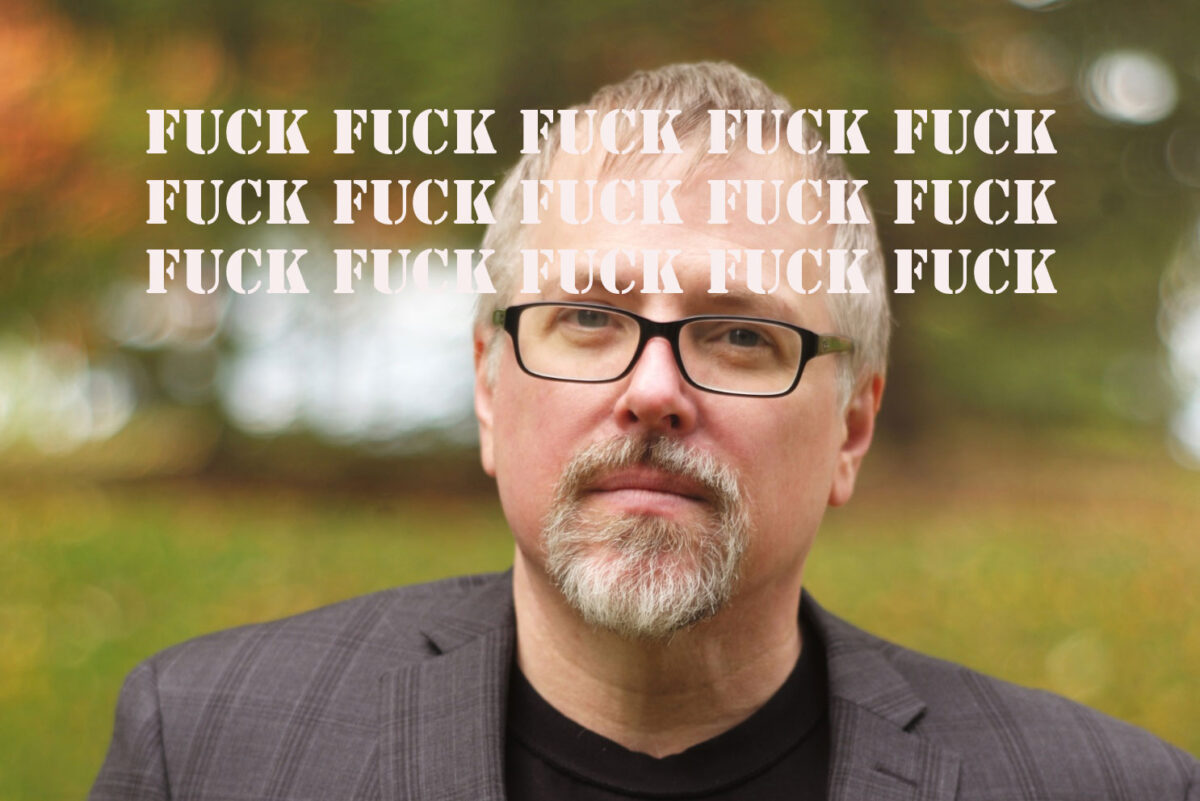

A few weeks ago, a friend asked me what happened between Jeff VanderMeer and me. And I told him over the phone. The memories reminded me what an abusive asshole Jeff had been to me. And I read Absolution, Jeff’s latest book, on Friday out of morbid curiosity. I was completely stunned and taken aback by how poorly written it was — particularly the third part, in which every sentence contained a “fuck” or two — and it was completely unconvincing. So I wrote a satirical review in the same preposterous and badly written form. (Yes, I was egged on by a few people who thought the results were hilarious.)

Jeff, who doesn’t possess a sense of humor and who is used to people kissing his ass, obviously wasn’t pleased. On December 28, 2024, at 11:33 AM — a mere eight hours after the review had been published (do I live in his head rent-free or is he more interested in practicing a literary form of the autocratic gaslighting dominance described by Ruth Ben-Ghiat in her excellent book Strongmen?) — VanderMeer claimed — falsely, as it turns out — that he would not read what I had written. His aim, of course, was to whip up hatred and present himself as the aggrieved “victim.” Any normal author — hell, any well-adjusted human being — would have laughed it off. But, you see, Jeff has always lived for the attention. He loves being the leader in his own cult of acolytes who will never question his “genius.” Seeing that everybody had piled onto his BlueSky post, while I was out and about having a fun time, Jeff spent late Saturday night doubling down on this. Typical behavior. For a guy who doesn’t care about anything I have to say, he certainly seems to have a lot of spare time on his hands doing precisely that!

I was initially fond of Jeff. In the summer of 2006, he had sent me a package containing his Ambergris stories. His writing voice back then was quirky, endearing, and filled with a sense of humanism. This was obviously a wacky original who wasn’t getting mainstream press coverage. So, of course, I happily set up a Bat Segundo interview, which aired on August 28, 2006.

We proceeded to correspond every so often with each other. I’d often receive a tortured message from him over some bad review. I have literally never known any author who cared so much about his press more than Jeff VanderMeer. And I replied, as I would (and have) to any writer, gently telling him to ignore the bastards. Then, on October 10, 2009, Jeff told me that he was going to be in town and that he wanted to either get together with a small group or do a “no holds barred” Bat Segundo interview. It was an extremely weird email that made me feel uncomfortable. At the time, I had already booked too many author interviews and was considering ending the show because I was burned out. And I politely informed him that I couldn’t do the second option, but that I was amenable to the first. I never wanted any guest to feel cheated. I gave my A game to everyone.

This meetup was the Westway Diner meeting I have already mentioned.

But sometime in December 2009 — in a post that Jeff has conveniently deleted and that cannot be found through the Wayback Machine — Jeff posted an unsettling post on “leverage” dripping with unbridled resentment for anyone who had spurned him. I had reason to be concerned. For Jeff had written about me in Booklife, viewing me in crassly mercantile terms that made me feel deeply uncomfortable. Thus began a correspondence in which Jeff lost his mind, which can be read in full below. Pay attention to the unhinged accusations that come out of nowhere and Jeff constantly monitoring my Twitter feed for any perceived sleight. (There was none.) Pay further attention to the extremely demented way in which Jeff demands fealty and puts forth conditional terms and the way he sees “threats” when none are there. This man was not well then, by any means. And I don’t think he’s improved in the intervening years. And also observe how understanding I was as Jeff was losing his shit and going well out of his way to find any new means of insulting me. Then again, for all I know, he was feigning an act of madness to manipulate me. That would certainly be on brand. Nobody, after all, ever questions the mad “genius.”

Date: December 29, 2009 5:49 PM

To: Jeff VanderMeer

From: Edward ChampionJeff:

While I can certainly see where you are coming from, there are significant problems with your approach to leverage, displayed in your post and (to some degree) in Booklife. While I didn’t find your stance as creepy as Jessa Crispin did, what I read is this: You are essentially viewing readers, advocates, and fellow people in the community as Bernaysian tools, completely ignoring the fact that they have inner souls. Yes, people can be advocates for your work. But they are often MORE than advocates. Discounting the rabid fanboys who wish to take up every spare whit of your time, well-adjusted people have thoughts and feelings and may not always be in the position to give you what you hope for. Their perceived failure may not necessarily be miserly and, as you point out in the comments, it may not simply be part of their personalities. But connections among people shouldn’t involve some permanent ledger in which you are constantly keeping a tally, which is how it’s coming across to me in your post. That’s just not a healthy way to carry on with people, either personally or professionally. I’m sure you know that, but I bring this up because it simply isn’t reflected in your blog post. If someone decides not to give you the press or the attention that you feel you deserve, there may be other extenuating circumstances existing outside the ones you’re speculating upon. Most of the time, simply ASKING the other person what’s up will clarify things. Direct communication, as we all know, is far healthier than idle speculation about a person’s motives. That way lies paranoia and crazy one million word diaries.

To present my own circumstances during your last tour: After doing anywhere from five to eight shows a month almost nonstop for four years, I was understandably burned out. There were many other contributing factors (being in a very shaky financial position, having a particularly humiliating stint with _______, and overcoming these considerable difficulties to continue work on the novel-in-progress, which has proven to be more fun and more challenging than I could have anticipated: thankfully, all this has been rectified in recent months). All this was going on in October (which was when you emailed me about it) and November. This is why I did not interview you for Segundo. I don’t wish to subject any author to a stale interlocutory approach or give any author a subpar experience because of any personal distractions. It isn’t fair to them. It isn’t fair to the listeners. (Segundo is now a weekly affair starting in 2010, which is one of my community services. I had to figure out a way to keep it going, because I know that it’s needed. Particularly since Silverblatt, despite remaining optimistic, has informed me that Bookworm is on thin ice.) The interview I told you about in person had actually been set up a few days before we met. Additionally, I would have gladly attended your New York appearance with Jeffrey Ford (for I dig both of you guys), had not __________, an individual who has gone out of his way to spread false and inaccurate information about me, been at the helm. Removing myself from the situation was a way for me to avoid any unpleasantness that might have infringed upon the undoubtedly pleasant proceedings, which were certainly not about me. I was also never sent copies of FINCH or BOOKLIFE, although I did manage to intercept the copy of FINCH that you sent Sarah. (KOSHER actually arrived a few days ago, and I look forward to reading this.) Given these multiple circumstances, there were understandable hiccups that had little to do with you. Best I could do was a friendly meetup. And, in fact, I canvassed Eric on interviewing you before he was in touch with Matt.

I drum all this up in the unlikely event that you may be obliquely corralling me within your category of miserly people, but also to inform you of the practicalities, limitations, and efforts of one person to deliver coverage to numerous people under dire conditions. When you make unspecified accusations (without citing a single example) about people being miserly with their leverage, I find this to be an inconsiderate position — possibly one that you didn’t intend. The fact that it is buttressed by the call for more people to take honest and controversial stands actually reinforces the very position that you are railing against. I’m sure I’m not the only person who feels this way.

I’m a no bullshit guy, Jeff, and, as you know, for any skirmishes, I’m happy to clarify or listen or atone. I’m not a big fan of passive aggression, although if someone doesn’t want to resolve something, I respect the time needed to come back to something. But you just can’t call everybody miserly like that. It may come across to some as selfish and ungrateful. I have to ask: In railing against the presumed misers, to what degree are you keeping quiet? To what degree are you truly to clear things up with the misers? These issues are nowhere in your post and that’s just as vital an aspect of relations as anything else.

Again, all this is a way of helping to flesh out an important issue to being a writing professional. If you don’t fully take into account these aspects, then you’re going to get more Jessa Crispins on your ass. And they’re not going to necessarily be direct about it.

In any event (and this may come across as an awkward segue), I sincerely hope that you and Ann had a grand holiday. Best wishes on all fronts and happy new year. And look forward to reading more of your material.

Thanks and all best,

Ed

* * *

Date: December 29, 2009 6:14 PM

To: Edward Champion

From: Jeff VanderMeerDude, you are totally misreading the post.

Jeff, replying from his phone…

* * *

Date: December 29, 2009 6:16 PM

To: Edward Champion

From: Jeff VanderMeerEd:

No it is not about you. It is not even about the subject you think it is about.

I tried to make it clear that I didn’t give a fuck whether you interviewed me or not.

Jeff, replying from his phone…

* * *

Date: December 29, 2009 6:23 PM

To: Edward Champion

From: Jeff VanderMeerAnd I don’t give a flying fuck about you and _____________. He was perfect for the gig, I wanted to meet him. I wasn’t going to sit there and go “how will this affect Ed Champion.”

What I objected to at our meal was an apparent *lack of directness.* I didn’t care about the interview–i cared about you apparently *lying* to me. In other words, you idiot, I don’t need friends who lie to me. Geez.

Jeff, replying from his phone…

* * *

Date: December 29, 2009 6:27 PM

To: Edward Champion

From: Jeff VanderMeerAnd as for booklife, you and Jessa form a small minority who’ve read the book that way. The vast majority have taken it as intended.

Jeff, replying from his phone…

* * *

Date: December 29, 2009 9:57 PM

To: Jeff VanderMeer

From: Edward ChampionSo I come back and I get four apoplectic emails from you sent from the worst possible medium — the iPhone.

What in the hell are you talking about? How did I lie to you?

* * *

Date: December 29, 2009 10:27 PM

To: Edward Champion

From: Jeff VanderMeerYou said you weren’t doing interviews then went on about all the interviews you’d done. You looked distinctly caught out when I mentioned it. I could care less about the interview. But I do care bout truthfulness and I don’t care for people who make it all about them. That’s all. I thought your email to me was pompous and full of yourself and deliberately misunderstanding points in the book. You’re very high maintainance I am not in the mood today.

Jeff, replying from his phone…

* * *

Date: December 29, 2009 11:14 PM

To: Jeff VanderMeer

From: Edward ChampionJeff:

For what it’s worth, I apologize for any verbal or non-verbal miscommunication. Clearly, some small unknowing gesture on my part upset you. But here’s where I’m coming from.

This is what I wrote to you on October 11th:

“I’m actually on hiatus from Segundo right now, and I’m doing my best to keep it this way. I got burned big time by an author who threw a temper tantrum after I had spent two weeks reading his books. And there have been numerous vocational setbacks that I won’t trouble you with. However, I would be happy to hang with you when you’re in town and just shoot the shit. I certainly look forward to reading FINCH.”

The interviews that I was talking about, as I recall, were a handful of people over a few weeks, which I had only scheduled a few days prior to meeting with you. I did not lie to you when I said (frazzled and burned out) that I was taking a hiatus from Segundo. This was true. At the time, I truly did not know if the show would continue. It took me weeks to figure out what I wanted to do, the circumstances of which I have already explained (not because I believed your post to be about me, but to give you an example of the internal complexities that you accuse so-called “miserly” types of). I then scheduled a small group of interviews (less than a handful) around that time. Largely to test the waters. I didn’t even have a fucking copy of FINCH until days before you came through New York, nor did I have a copy of BOOKLIFE until you handed me an extra one at the diner. So even if I wanted to, there was really no way I could schedule enough time to read your books and prepare for the interview. Unless it’s a film person, I need at least two weeks prep time for an author.

So, no, Jeff, I did not lie to you. There was no way I could have conducted the interview given the timetable.

At the time you brought up the Segundo thing, as I recall, you laughed the whole thing off. You never indicated that you were pissed off. And for all of your talk about truthfulness (or “truthiness,” which seems more applicable in this case), you never once leveled with me. So I’m baffled by your accusations of pomposity and deliberate misunderstanding of points in the book (in fact, I was more addressing your blog post rather than BOOKLIFE proper).

I’m going to chalk up your accusations here to being tired, exhausted, or some outside contributing factor beyond my ken. But I will say that calling people who have your fucking back “pompous,” “high maintenance,” and “apparently lying” is NOT cool, Jeff, and unacceptable. Particularly when none of these modifiers are applicable. For a guy who professes to value leverage, you’re doing a heck of a job chasing away your allies.

Sincerely,

Ed

* * *

Date: December 29, 2009 11:48 PM

To: Edward Champion

From: Jeff VanderMeerWhatever. I am happy to put it to miscommunication rather than a lie. But I did put it to you pointedly, whether with a laugh or not. You never said you didn’t have either book. I have never felt one way or the other that you had my back.

But I am telling you now that to misinterpret my post and my book, especially knowing me and my record, is pretty piss poor. And while I don’t think of you as miserly, you’re not on my top fifty most generous people out there, either.

I was delighted to have a chance to talk. I could care less about being interviewed. Is this clear? I almost feel like you’re upset you didn’t get review copies. I was fairly sure you had, but there must’ve been a glitch with the publisher.

I am not tired or particularly upset. I am mostly not interested in being called a soulless PR hack. Have you read my books, dude? They’re fucking strange. I have to work twice as hard as most people to find my audience. So I don’t appreciate it. I suppose by your measure of things I should sink back into the mire and be happy with an audience of 1k instead of 20k.

I wish you could walk in the shoes of a published novelist for a fucking year. You’d understand then just how complex all of these dynamics are.

But mostly…man, I say writers should use their political capital to do good works…and you twist that simple, decent message into something shitty. C’mon.

I am not interested in having you as an ally. You aren’t getting anything from me for review. I am never doing your show. Do you get it? You can be relieved you’re off the chessboard. Since that’s how you think I see things.

Jesus.

Jeff, replying from his phone…

* * *

Date: December 29, 2009 11:58 PM

To: Edward Champion

From: Jeff VanderMeerI am happy to be your friend, but as I said I am taking ally off the table.

Jeff, replying from his phone…

* * *

Date: December 30, 2009 12:04 AM

To: Edward Champion

From: Jeff VanderMeerAnd what was that stupid sophomoric twitter message conflating me and Lethem a little while back?

Jeff, replying from his phone…

* * *

Date: December 30, 2009 12:10 AM

To: Jeff VanderMeer

From: Edward ChampionDon’t email me again. You’re way out of line. And unless you atone big time, you’re neither a friend nor an ally. I’m done with you. You fucked up big time.

I truly thought better of you.

Saddened and disappointed,

Ed

* * *

Date: December 30, 2009 12:18 AM

To: Edward Champion

From: Jeff VanderMeerWhatever. I am still your friend.

I have your back as your friend, but I am not interesting in dealing with you on a professional level. It’s too much work.

*You* don’t even have to apologize, although you should.

As for the fucked up big time–i am your friend, but if that’s a threat, it’d be best if you withdrew it immediately.

Jeff, replying from his phone…

* * *

Date: December 30, 2009 12:28 AM

To: Edward Champion

From: Jeff VanderMeerAnd I am happy to apologize regardless, but only in the context of it being understood that I am not sending you review copies and I am not interested in ever being on your show. Otherwise, an apology seems like a way to gain an advantage.

Your email set me off because I do consider us friends and I expect you to give me the benefit of the doubt. I certainly have done the same for you re several of your blog posts in the past.

So, apologies. And thanks for calming me down when the Crispin thing happened.

And I know you have had some reversals of late, and I know it hasn’t been easy for you until recently.

PS clearly if I saw people as merely contacts none of this exchange would’ve occurred. I would’ve doffed my hat, said “yer right, guv’nor” and gone on with my life.

Jeff, replying from his phone…

* * *

Date: December 30, 2009 12:35 AM

To: Jeff VanderMeer

From: Edward ChampionYou’re drunk. Get some sleep and contact me when you have a clear head.

* * *

Date: December 30, 2009 12:37 AM

To: Edward Champion

From: Jeff VanderMeerI am not drunk. I am apologizing.

jeffrog the tarded

Jeff, replying from his phone…

* * *

Date: December 30, 2009 9:14 AM

To: Edward Champion

From: Jeff VanderMeerRight. It is morning. I am sorry for the vitriol. I am firm on the friends and taking you off the reviewer list. I just don’t see any other way to proceed. I just think it simplifies things.

I see now that I think you were trying to extend an olive branch. But I hope you see my point, too.

Jeff, replying from his phone…

* * *

Date: December 30, 2009 9:43 AM

To: Jeff VanderMeer

From: Edward ChampionJeff:

I don’t do conditional friendship. Your actions were way out of line. Get some help. I do wish you the best.

Sincerely,

Ed

* * *

Date: December 30, 2009 9:49 AM

To: Edward Champion

From: Jeff VanderMeerWow. You really do see people as binaries. Amazing. So I take out the element that would *get in the way of friendship*, the part that would leave a suspicion of manipulation, and you can’t hack it. Amazing. After starting this with your amazingly self-absorbed email. Amazing.

Maybe you need a wake-up call. There is not one person I met in NYC who, when I mentioned your name, had anything good to say about you. I had to spend a good deal of time defending you. No more.

Well, have a nice life. If you ever come to your senses, email me.

Jeff, replying from his phone…

* * *

Date: December 30, 2009 9:50 AM

To: Edward Champion

From: Jeff VanderMeerWay out of line. You’re just too used to authors sucking up to you. You’re a total hypocrite on this issue of leverage.

Jeff, replying from his phone…

* * *

Date: December 30, 2009 10:37 AM

To: Jeff VanderMeer

From: Edward ChampionJeff:

This exchange has clearly moved into the Twilight Zone.

So here’s the deal. If you want to resolve this, then we need to do this by phone. Call me at 718-XXX-XXXX. Because clearly there is something here you are not communicating to me or you are deliberately misreading my emails (or vice versa). The conversation must be relatively calm, honest, civil, and we must listen to each other.

Sincerely,

Ed

* * *

Date: December 30, 2009 11:12 AM

To: Edward Champion

From: Jeff VanderMeerEd:

You need to actually read my emails. I hold no ill-will toward you, but you

are not following my train of thought here. I don’t think a phone call

solves anything. I think you and I should take a break from communicating

for a month or two and then talk. But I’m firm on this–I am not having

anything to do with your show or you as a reviewer. That is off the table,

and it’s not pejorative–I often, without saying it, don’t send stuff to a

reviewer or a podcaster if I become friends with them because I feel it

becomes a conflict of interest. It’s just overt here.More importantly, I’m too busy to take a phone call. I’ve got 1,000,000

words of anthos to deliver by May 1st.All apologies,

Jeff

* * *

Date: December 30, 2009 11:12 AM

To: Edward Champion

From: Jeff VanderMeer

Subject: in any event, peaceHave a good New Year’s, man, and don’t let any of this worry you. Here’s to a good 2010.

Jeff

* * *

Date: December 30, 2009 11:57 AM

To: Jeff VanderMeer

From: Edward ChampionYou too. Let’s cool off and return to this in less frazzled and considerably calmer circumstances.

Thanks and all best,

Ed

* * *

Date: December 30, 2009 12:10 PM

To: Edward Champion

From: Jeff VanderMeerSure, no problem. And apologies for the vitriol. It is true I’m under tremendous pressure right now.

Have a good one.

jeff