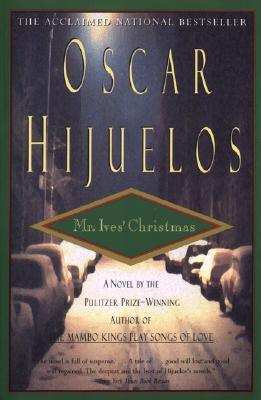

Victoria Wilson is most recently the author of A Life of Barbara Stanwyck: Steel-True, 1907-1940.

Author: Victoria Wilson

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Subjects Discussed: Stanwyck shifting from being known as “Frank Fay’s husband” to being the dominant breadwinner in a matter of years, when Frank Fay was a washed-up actor spending Stanwyck’s money, Jimmy Cagney taking his inspiration from Frank Fay, Stanwyck learning how to simplify her acting, Fay’s alcoholism, Stanwyck’s initial hatred for Hollywood, Fay being ahead of his time, Frank Fay as the origin point of standup comedy, Stanwyck’s early fractious relationship with Frank Capra, the frustration of endless screen tests, Meet John Doe, Ladies of Leisure, Stanwyck’s defiance and resentment, how Fay helped Stanwyck get her big break, Stanwyck’s near-affair with Capra, difficult actors, Stanwyck’s aversion to parties, Stanwyck and class distinctions, how Stanwyck closed the iron door on a lot of people, Stanwyck shutting out Mae Clarke, Clarke and Cagney’s grapefruit, Stanwyck’s conservative politics, anti-Roosevelt actors, Republicanism vs. modern conservatism, the gold standard, Stanwyck becoming more discerning with her politics with Robert Taylor, Stanwyck’s acts of generosity, unemployment during the Depression, Stanwcyk’s literacy, being an autodidact, Stanwyck and Katharine Hepburn, how Stanwyck cultivated her modernity, how Stanwyck networked, reading a book at a party, Stanwyck’s shyness, Frank Fay’s attempts to kidnap his adopted son, how Wilson tracked down Dion Anthony Fay (Stanwyck’s son) in the pre-Internet age, mysterious investigators, sinister methods of finding sources, Stanwyck’s clothes, motherly love, when Stanwyck accidentally wore a dress backwards, the moral assaults on unmarried Hollywood couples living together, Clark Gable’s forced marriage to Carol Lombard, how Stanwyck and Robert Taylor were encouraged to marry, the Hays Production Code’s hold on the private life of actors, Stonewall, Olivia de Havilland’s resistance, Stanwyck teaching younger men how to act, Stanwyck’s relationship with Robert Wagner, Joel McCrea, Stanwyck identifying herself as the masculine presence in relationships, what contributed to the dying years of the Stanwyck/Taylor marriage, Stanwyck’s monogamy and possible affairs late in the Taylor marriage, Harry Hay, a secret anecdote from Anthony Quinn, Stanwyck’s involvement with Gary Cooper, Stanwyck’s unexpected nude appearance before a crowd at a surprise birthday party, what conditions cause a biographer to trust a source, Stanwyck and Joan Crawford, Al Jolson’s assault on Stanwyck, editorial forensics, determining authenticity, how Wilson used her editorial background to determine the accuracy of a fanzine report on Stanwyck, the balance between facts and imagination, Wilson’s set of rules, avoiding movie star biography tropes, the difficulty of getting Richard Chamberlain to talk, the differences between today’s media-trained actors and yesterday’s more open actors, Robert Stack, when actors once drove to their own screenings, building trust with sources, Wilson’s formidable fanzine collection and her efforts to preserve it, some details about the second Stanwyck volume, the end of the studio system, Stanwyck’s willingness to work in television, and how talent makes you larger than the time.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: So let’s talk about Ruby Stevens, aka Barbara Stanwyck. She had one of the most formidable work ethics I think I have ever read about of any Hollywood actress of that time. I mean, she worked after she fell down the stairs, her right leg shorter than the left during Ten Cents a Dance. She toiled through that. She toiled through a painful leg injury that she had in Ever in My Heart. She would run lines with other actors when she was completely exhausted, after a long shift.

Wilson: Ed, I’m happy to say that I can see you’ve read the book.

Correspondent: I have read the book. Yes. She kept her costume and her makeup on, even when she was asked to go home for the day because she figured that a director would ask her to work. So my question — and this is a good way of getting into her origins here in Brooklyn. How did this work ethic originate? I mean, I’m wondering if she had some sort of incident in her early showgirl days or her early Broadway days where she may have flubbed a line and she figured that committing everything to memory and also always being there was going to be the absolute advantage that she would have over everyone else. So I was hoping you could talk about this and unpack this incredible ethic that she had.

Wilson: Well, let me see if I can unravel this mystery. To begin with, Stanwyck knew — what she did learn — you’re right in that she did learn in being in shows on Broadway and being in other kinds of shows. Revues. Which she said. She could always be replaced. And she understood that. But what she got, well, it wasn’t really one specific incident. I think, given the childhood that she had, the most important thing to her, speaking of Baby Face, was for her to be able to get out. She wanted to get out and she didn’t want to go back to that. And her sister brought her into her world — the sister who was an actress and who was a dancer, etcetera etcetera. She loved her sister. And she loved that world because it allowed her to escape in her head what the circumstances were of her life. And that world, that theater world, that world of working actors was her way out. It was her road out. And combining that with a need to understand that she could be fired or replaced at any time, over time she and the people who she admired were serious workers. And I think it all combined to give her that work ethic.

Correspondent: Well, I’m wondering. Obviously this book only goes up to 1940. Did this particular work ethic ever dissipate in her later years?

Wilson: Never.

Correspondent: Never. Wow.

Wilson: And at a certain point in the early ’50s, when she absolutely could not get a job, it was a torment to her. Because it was an honest day’s pay for an honest day’s work. And that was what you did. And it didn’t matter if it was 90 degrees and she had on all this makeup. At one point, Mitchell Leisen said, “For god’s sake, loosen that corset.” “No, you may need me.” And when she had to do a scene over again because another actor — there’s a story, again, in Volume 2, when she’s making Clash by Night and Marilyn Monroe keeps screwing up the line. And she has to pack that suitcase. She unpacked that suitcase in exactly the way that it had to be packed before the prop men could get there. But it was all perfect. And that was another thing that interested her about radio. Because the voice had to be perfect. And it had to be so modulated to express everything that had to be expressed. But she had that discipline.

Correspondent: I alluded in this question to the fact that she would memorize the entire script, transcribing it out multiple times, and she would know not only her lines, but everybody else’s lines. And this Marilyn Monroe story you mentioned, which is in the next volume, has me curious about the level of tolerance she had for other actors. I mean, she was pretty brutal on Joel McCrea, which I’ll get into later on. But I’m wondering how this method originated and why knowing every single angle like this was essential to her. And also, in light of the fact that she did a lot of improvisation, how that worked into this steel memory. This almost military-like work ethic which we’ve been discussing here.

Wilson: Well, actually, she didn’t do improvisation in terms of veering away from the script. She was absolutely disciplined about that. But I think that there’s one word to describe why she did what she did and that word is fear. Not something that people associate with Barbara Stanwyck, but there was a lot of fear around her and, over that, there was the overlay that drove her. And I think that she thought she needed to get it perfect. I mean, at the beginning, she was thrown by the way these movies were made. And she wanted to be in command, in control, so that she could be able to pick it up at any point and also I think she got something out of the fact that she knew everybody else’s part. But I do think, at the heart of it, it was fear.

Correspondent: Fear. This is interesting. Because I was kind of curious about these early Broadway days. She has great success with The Noose. But I’m wondering, given that it took probably another decade or two for her comedic instincts to really come out in, of course, The Lady Eve and Ball of Fire, I’m wondering how that particular play reinforced certain acting tics or certain acting methods. Were you able to find out anything through your very meticulous research about what that play did to get her going and to get her adjusting?

Wilson: Well, now that’s a very interesting story. Because what she has always done — and the thing about working with Barbara Stanwyck for fifteen years is that she was not a liar. She was honest. I’ve caught her in a couple of inventions, which were self-protective. I suppose most lies are.

Correspondent: Such as what? What were those particular lies?

Wilson: Well, she said that she could not have children because she was a bleeder. Okay, let’s put it this way. If you’re a bleeder, you’re not doing your own stunts. You’re not riding horses the way she rode horses. You’re not taking falls the way she took falls. You’re just not doing that. She had an abortion at a certain age and it was a terrible abortion. And she couldn’t have children.

Correspondent: At twelve?

Wilson: (pause, unanswered) So there’s that. I mean, but other than that, in another few instances, she was somebody who basically was straight up honest. Steel true and blade straight. And so what I started to say was in The Noose, she always reported that it was Willard Mack who taught her everything she needed to know for that play. But it wasn’t just Willard Mack. It was Mrs. Harris. Mrs. Renee Harris, who was the widow, the last surviving person, which I write about, to get off the Titanic as it was sinking, who was the person who spotted her and who gave her the larger part and who worked with her until Willard Mack came back from New York, where he was looking for another actress and had sent up Francine Larrimore, who was going to take the part. Once Willard Mack came back to work with her to join the show, and said, “Alright, you can do it out-of-town until we get to New York,” he was the one who worked with her and really just taught her everything. And, you know, I write about what happened to theater after the First World War, where it became much more naturalistic. The Noose itself, written by Willard Mack, was an attempt to be more naturalistic in terms of showing the realities of how people talked and how people in nightclubs talked and how lowdowns would talk. It was like this was supposed to be the real thing. And that’s what he was interested in capturing. It wasn’t artifice anymore. Or melodrama. I mean, the play is somewhat melodramatic. It is still of its time. But I do think that it was a combination of Willard Mack and then, when she goes to make burlesque, unless I’m getting ahead of you.

Correspondent: No. I’m hearing you.

Wilson: When she goes to make burlesque, she’s working with Arthur Hopkins, one of the great directors and producers, who also was very involved in naturalism. And again, he helped her strip herself down and simplify her work. And then, of course, who does she end up with and who was she in awe of? Long before she met him? That was Frank Fay, who was as simple and unadorned as a performer as you could possibly be.

Correspondent: Yeah. Well, I’m wondering. She is operating off of fear, as you say. The book regrettably does not get as far as Double Indemnity, where Billy Wilder basically cajoles her into the role by saying, “Are you a mouse or are you an actress?” So it seems to me that she was still driven by fear in terms of what her range was likely to be. Is that safe to say?

Wilson: Well, I don’t think — look, when you’re asking me that one question, I say she wrote it down because of fear. She did this because of fear. I mean, yes, in a way, it was fear. But it was fear coupled with a whole range of other emotions. And one of them was determination to get the hell out from where she came, to make sure she never had to go back there. So I think that it wasn’t just fear.

Correspondent: Well, in terms of developing a range, when do you think she became aware that she could more than either cry on stage or be a very physical performer? I mean, did she know this fairly early on? Based off of what I mentioned about Billy Wilder, it seems that even after being nominated for Stella Dallas, she still didn’t realize what she could do. Or did she?

Wilson: No, she did. Because it was earlier, before Stella Dallas. I mean, people didn’t know this, but what I discovered and what I put together is that it was Zeppo Marx, who basically said, “You can do comedy,” and who pushed her roles in those minor movies where it was Breakfast for Two or The Mad Miss Manton, which was later. But it was those. The Runaway Bride, which was supposed to be a kind of Frank Capraesque, It Happened One Night, which, believe me, it wasn’t. But it’s an interesting movie for a lot of other reasons. Where she tries to do a kind of screwball comedy. And she was terrified of that. But she tried it. And the one thing she understood was, if you’re going to do just one thing and you’re just going to play it, you’re screwed.

Correspondent: It’s also interesting, this period where she’s at Columbia, where she’s about to jump to another studio. But, of course, she has to fulfill her contract. And she is quite adamant, even during the Great Depression, about sticking for that $50,000 figure. And I was curious about that. I mean, money was certainly a drive for her to act in the pictures. But how did that interplay with this range that you say she knew she had and that was actually urged on later by Zeppo Marx, who was her manager.

Wilson: Well, I don’t know at that point, when she was fighting for that contract at Colubmia Pictures, for that raise, that it was about her range. It was about her…

Correspondent: Respect?

Wilson: Well, I think it was about her looking at Constance Bennett and Ann Harding and seeing what they were making and saying, “I can damn well do that too.” I mean, the thing about her is that she didn’t have — from a very early age, there was nobody who was really fighting her battles, except for Ruby Stevens. And even after she married Frank Fay, he says to her — one days, she’s upset — he says, “You can tell me. I’m here for you.” It wasn’t a natural impulse for her. It wasn’t the kind of thing that she could rely upon a mommy or daddy. She had no mommy or daddy. And so when you do that, which is the perfect training for her in terms of the choices she made in Hollywood, which was living outside of that studio system as much as she could. And then, by that point, she could rely on Frank Fay. And she could see what she was doing. She could see the response. She could see how her career was building. And I think she just said, “Screw this. This is what I’m going to do.” And I also think that there’s something to be said about the bond that she had with Frank Fay, which basically was a bond that brought them together and excluded the rest of Hollywood. Because they were excluded and they became isolated and more isolated and this reproduced itself. So I think her attitude was “Screw this. I don’t need you. We’re onto ourselves and we’re going to be just fine.”

The Bat Segundo Show #531: Victoria Wilson (Download MP3)