(This is the twenty-seventh entry in The Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge, an ambitious project to read and write about the Modern Library Nonfiction books from #100 to #1. There is also The Modern Library Reading Challenge, a fiction-based counterpart to this list. Previous entry: Florence Nightingale.)

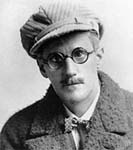

“Mr. Joyce, first of all, is a little bourgeois Irishman of provincial tastes who has spent a lifetime on the continent of Europe in a completely fruitless attempt to overcome the Jesuit bigotry, prejudice, and narrowness of his childhood training. Mr. Joyce began his literary career as a fifth-rate poet, from there proceeded to become a seventh-rate short-story writer, graduated from his mastery in this field into a ninth-rate dramatist, from this developed into a thirteenth-rate practitioner of literary Mumbo-Jumboism which is now held in high esteem by the Cultured Few and I believe is now engaged in the concoction of a piece of twenty-seventh-rate incoherency, as if the possibilities in this field had not already been exhausted by the master’s preceding opus.” — Thomas Wolfe, The Web and the Rock

James Joyce was probably the greatest writer of the 20th century, although opinions vary. (Many of today’s young whipper-snappers sound astonishingly similar to a dead-inside academic like Thomas Wolfe’s Mr. Malone when dispensing their rectal-tight rectitude and uncomprehending pooh-poohs on social media.) But as a wildly ambitious literary athlete nearing fifty (353 books read so far this year, with a little more than a week left), I cannot think of any other writer whom I have returned to with such regularity and gusto. Even the dreaded “Oxen of the Sun” chapter in Ulysses, which caused at least six hundred grad students to faint from fatigue in the last year (and a good dozen young scholars to permanently lose their minds), demands that you peruse it anew to appreciate its multitudinous parodies.

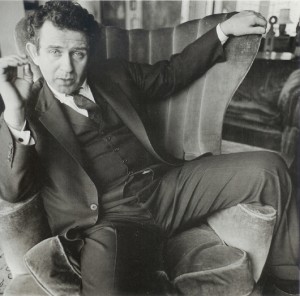

Only a handful of living writers can summon a similar obsession in me through the power of their words. But even when these hypergraphic bards descend from the Mount with their thick portentous volumes, they are hopelessly outmatched by the Dublin bard’s mighty polyglot yardstick. (Certainly Anthony Burgess spent his prolific literary career forever lost in Joyce’s formidable fug and forever resented the fact that his best known work, A Clockwork Orange, with its captivating NADSAT, caught on, perhaps because it represented some attempt to mimic Joyce’s word-soaked playfulness.)

When I visited the Martello Tower at Sandycove Point not long before the pandemic, it was the closest thing that an atheist like me has ever had to a religious experience. It had never occurred to me — a relentlessly abused white trash kid who fought off bullies (and still has to do so in his forties) when not filling his voracious noggin with too many books, a reader from the age of two, an accidental provocateur who still manages to piss off PhDs and varying mediocre literary types whenever I quote long passages from memory culled from books they claim to have read but have somehow forgotten — that I would ever have the divine privilege of standing at the very location where “Telemachus” begins. My first walk alongside the Mississippi River last summer in deference to another literary hero of mine was close, but Joyce was the clear winner when it came to summoning such heartfelt psychogeographical wonder. As I sauntered along the swerve of shore to bend of Scotsman’s Bay back to the Dublin train, I trembled with tears of joy, feeling great shudders push me into a state of awe that I did not know was writhing within me. I simply could not believe it. I had already been impressed by the social code of the great Irish people, who would always give you at least five minutes of banter and who were never shy in expressing their opinions and who immediately unlocked the key to further appreciating “Ivy Day in the Committee Room” through their innate conversational finesse. But was I actually standing in the same room in which Samuel Trench (the basis for Haines) had shot at an imaginary panther that had plagued him in his sleep? And was that truly Joyce’s guitar? The good people who run this landmark were incredibly kind to this wildly voluble and incredibly excited Brooklynite. I flooded their robust Irish souls with endless questions and an irrepressible giddiness. A kind woman, who did her best to suppress laughter over my ostentatious literary exuberance, remarked that they had not seen such a visitor display such bountiful passion in months.

But I am and always will be a Joyce stan. I own five Joyce T-shirts, including an artsy one in which the opening words of Finnegans Wake are arranged in a pattern matching one of Joyce’s most iconic photographs. Before I deleted all of my TikTok accounts, my handles were various riffs on Joyce’s most difficult volume. There has rarely been a week in which I have not thought about Ulysses or “The Dead” or, on a whim or in need of a dependable method to restore my soul, picked up my well-thumbed copy of Finnegans Wake and recited pages and laughed my head off. When I went through the roughest patches of my life nine years ago, it was James Joyce who helped save me. I reread Ulysses while living in a homeless shelter. And had I not had that vital volume on me to renew my fortitude and passion, it is quite likely that I would be dead in a ditch somewhere and that the words I am presently writing would not exist.

So I’m obviously already in the tank for Joyce and deeply grateful to him. He has proven more reliable and loyal to me than my toxic sociopathic family. These moments I have chronicled would be enough. But Richard Ellmann hath made my cup runneth over. He somehow achieved the unthinkable, writing what is probably the best literary biography of all time. Other biographers have combed through archives and badgered aging sources, hoping to stitch their tawdry bits with dubious “scholarship.” Small wonder that Joyce himself referred to these highfalutin ransackers, who have more in common with TMZ reporters than academics, as “biografiends.”

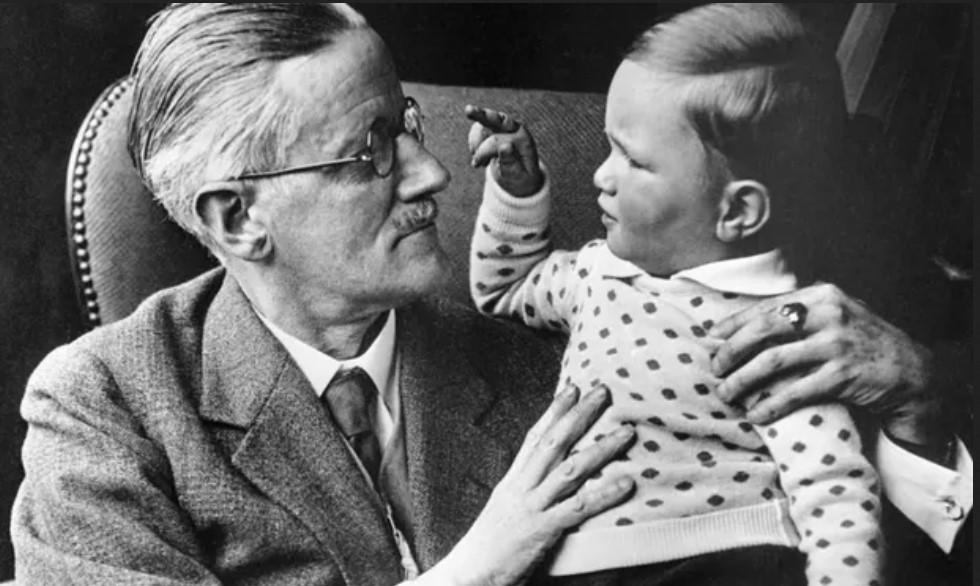

But one cannot lay such a mildewed wreath at Ellmann’s feet. There are very few details in Ellmann’s book that do not relate directly to the work. We learn just how invaluable Stanislaus Joyce was to his brother. Stanislaus — an adept peacemaker who documented his fractious fraternal relationship in his own book, My Brother’s Keeper — is liberally excerpted. If Stanislaus hadn’t pushed back hard on the alleged “Russian” feel of Joyce’s great short story “Counterparts,” would we have had “The Dead”? (“The Dead” was written three years after the other fourteen tales contained in Dubliners.) To cite just one of many Ellmann’s cogent connections between Joyce’s life and work, we learn that Edy Boardman — Gertie McDowell’s friend in the “Nausicaa” chapter of Ulysses — represented faithful recreations of neighbors that the Joyce family knew on North Richmond Street and that “the boy that had the bicycle always riding up and down in front of her window” was, in fact, a callout to one Eddie Boardman, who had the first pneumatic-tired bike in the hood. Joyce’s crazed jealousy towards any man whom he suspected had designs on Nora Barnacle — with his insecure interrogations of Nora by letter and in person — are duly chronicled. The boy that Nora had dated before Joyce came along was Sonny Bodkin (who died tragically young of tuberculosis) and she was initially attracted to Joyce because of their close physical resemblance. And while Joyce was forward-thinking when it came to presenting Jewish life in Dublin (and arguably creating one of the most fully realized Jewish heroes in literature with Leopold Bloom), his regressive masculinity could not stand the notion that his great love’s heart had stirred long before he came along. And yet, even with his nasty and unfair and unreasonable accusations, he was able to find a way to broach this in fiction with Gretta Conroy recalling her dead lover Michael Furrey in “The Dead.” It is often the darkest personal moments that fuel the best of fiction.

And let’s talk about that ugly side of Joyce. The great Dublin exile was also an unapologetic leech, a shrewd manipulator, and a master of dodging creditors. He fantasized about pimping his wife Nora out to other men while also being naive enough to believe Vincent Cosgrave’s claim that Cosgrave was sleeping with Nora before him in the fateful summer of 1904, nearly sabotaging his relationship with a series of angsty transcontinental missives. For better or worse, Joyce refused to see the full extent of his poor daughter Lucia’s troubles. He treated many who helped him very poorly. And, of course, he despised explaining his work. He wanted to keep the scholars busy for centuries. And he succeeded. Here we are still discussing him, still mesmerized by him. Even when his life and work are often infuriating.

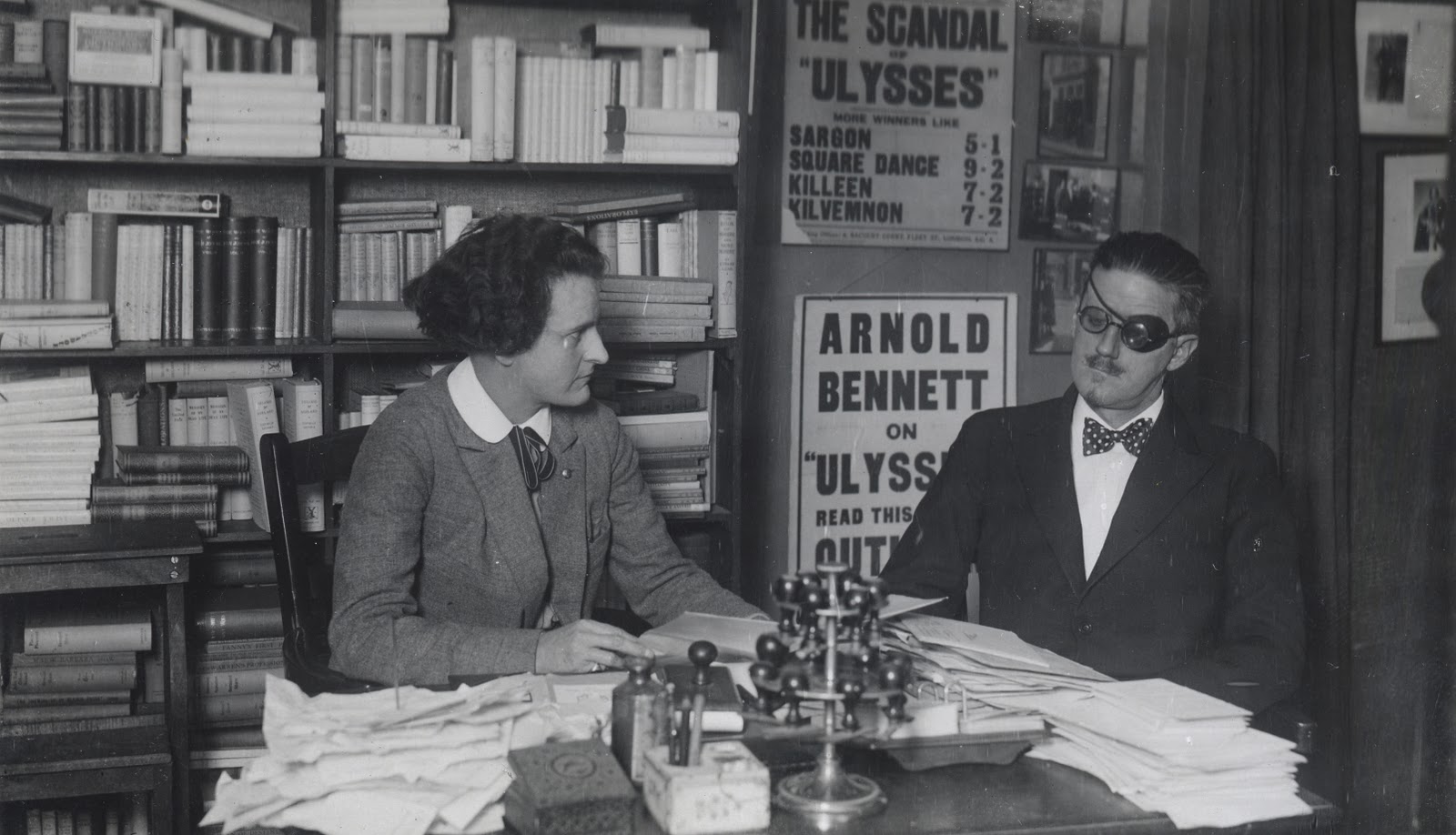

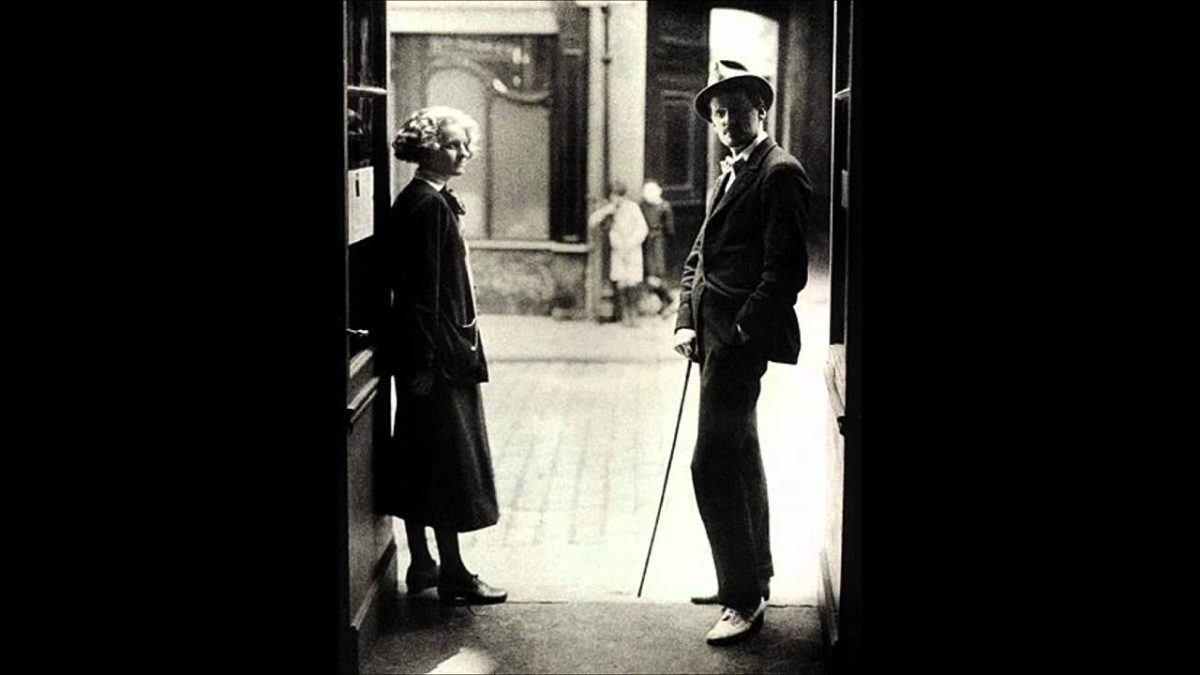

If there is any weakness to Ellmann’s formidable scholarship, it is with the women who were vital to Joyce’s life. Ellmann was so focused on finding precise parallels between Joyce’s life and work — but usually only including Jim and his brother Stanislaus at the center — that he often portrays these invaluable lieutenants in superficial terms — that is, if he even mentions them at all. Let us not forget that Joyce was a man terrified of dogs, violence, and thunderstorms. The women in his life empathized with the effete qualities of this indisputable genius and provided financial and scholarly resources for Joyce to continue his work, even when they found Finnegans Wake baffling and not to their taste. Perhaps most criminally, there is no mention in Ellmann’s book of Myrsine Moschos (who was Lucia Joyce’s lover at one point), the dutiful woman who toiled at the famous bookstore Shakespeare & Company and spent long days in the dank chambers of Parisian libraries, sifting through decaying volumes that often crumbled to dust in search of obscure words and other arcane lexical associations that Joyce included in Finnegans Wake. Moschos often returned from these scholarly journeys so exhausted that Sylvia Beach — arguably the greatest bookseller in all of human history and the woman who took significant risks to get Ulysses published — had stern words for Joyce about Moschos’s health.

In 2011, Gordon Bowker published a biography — something of a quixotic project, given the long imposing shadow cast by Ellmann — that was more inclusive of Nora Barnacle, Sylvia Beach, and Harriet Shaw Weaver. But I do recommend Brenda Maddox’s Nora, Carol Loeb Schloss’s Lucia Joyce: To Dance in the Wake (with significant reservations), and Noel Riley Fitch’s Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation as volumes that fill in these significant gaps that Ellmann, in his efforts to portray Joyce as his own master, often failed to address. (Even Jo Davidson, the sculptor who was instrumental in making the New York theatrical run of Joyce’s play Exiles happen, is merely afforded a footnote by Ellmann.)

Can one literary biography be the all-encompassing volume that captures a life? Even one that was as complicated as Joyce’s? Perhaps not. But Ellmann has certainly come closest. Now that Joyce’s famously hostile grandson Stephen has passed away and the copyright for much of Joyce’s work has at long last been released into the public domain, it’s possible that another biographer will be better situated to come closer to revealing the Joyce mystique without being strangled by the bitter hands of some unremarkable apple twice removed from the great tree. But I doubt that any future scholar will match Ellmann. For all of his modest limitations, he was the right man at the right time to capture a seminal literary life in perspicacious and tremendously helpful form.

(Next Up: Elaine Pagels’s The Gnostic Gospels!)

It has been five years since I last tendered any heartfelt words about 20th century fiction for the Modern Library Reading Challenge. An infernal yet magnificent Irish genius is to blame for the delay. Five years is frankly too damned long, especially if I hope to complete this massive and somewhat insane project before I croak my own answer to Joyce’s “Does nobody understand?” Frank Delaney’s

It has been five years since I last tendered any heartfelt words about 20th century fiction for the Modern Library Reading Challenge. An infernal yet magnificent Irish genius is to blame for the delay. Five years is frankly too damned long, especially if I hope to complete this massive and somewhat insane project before I croak my own answer to Joyce’s “Does nobody understand?” Frank Delaney’s