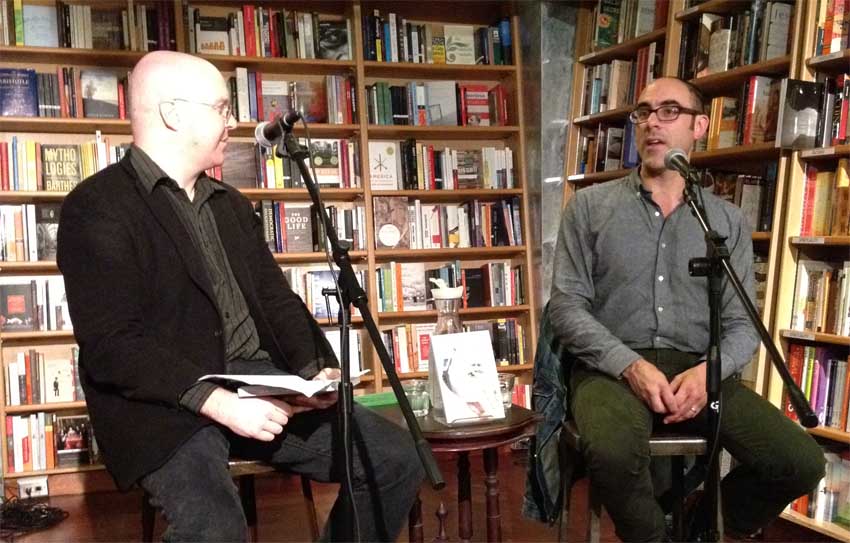

Greg Sestero and Tom Bissell are the co-authors of The Disaster Artist: My Life Inside The Room, a book which documents the making of The Room. Bissell previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #449 and The Bat Segundo Show #450.

Authors: Greg Sestero and Tom Bissell

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Subjects Discussed: Ideal Hollywood standing positions to check smartphones, being addicted to technology, how Sestero and Bissell collaborated, Tommy Wiseau’s vernacular, how the Wiseau philosophy is applicable to real life, The Talented Mr. Ripley, Patricia Highsmith’s unanticipated influence on The Room, Wiseau’s thoughts on Fight Club, why Sestero put up with Tommy Wiseau for so long, Robin Williams vs. Tommy Wiseau, Patch Adams, a melodramatic video that Wiseau photographed and sent to an insurance company, the blind and reckless Hollywood producer attitude, Brad Pitt, the unspeakable display of Tommy Wiseau’s ass, Wiseau’s philosophy on shooting sex scenes, Bon Jovi’s reluctance to collaborate with Wiseau, getting music for The Room, composers hired by Tommy Wiseau, shooting The Room simultaneously in 35mm and HD, Wiseau’s curious innovations, Citizen Kane, being the first person to build a private bathroom on set, Hitchcock’s aversion to shooting on location, The Birds, Wiseau’s cinematic influences, “Cinema Crudité,” Wiseau’s Berlin Wall of personal involvement, occupying a territory (and a life) that is half invention and half real, Wiseau’s mysterious past in Europe, incidents from The Room pulled from real life, the Bay to Breakers race, Wiseau’s efforts to cash out-of-state checks, The Room as Wiseau’s secret autobiography, Wiseau’s fixation on James Dean, Giant, actors who dye their hair, A Rebel Without a Cause, Marlon Brando, whether Sestero’s involvement in The Room made any dents in his acting career, the challenges of conveying incomprehensible dialogue, the advantages of knowing people named Tom, penetrating into the great mystery of Mark’s disappearing beard in The Room, being nicknamed “Babyface” in acting class, being photographed being shaven, the film set as a surveillance state, crew members on The Room who worked simultaneously on Terminator 3, Wiseau’s fixation on youth, The Room as a parallel identity for Wiseau, parallels between The Room and Grand Theft Auto, The Room video game, and Bissell’s open letter to Niko Bellic.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I’m curious about how you guys both wrote this book. There are large chunks of dialogue between Greg and Tommy Wiseau. And it’s often so specific that I can’t imagine how you could get it that specific after several years had passed. So I’m wondering. I have to assume much of it is invented. Tom, you happened to share Tommy’s name. Did you two talk to each other in a dark room? You with the Wiseau accent? How did this come about? The dialogue in this book? To flesh out the big important story behind The Room.

Bissell: Well, Greg and I recorded all these chapters. We have like thirty hours of tape.

Correspondent: Oh!

Bissell: And Greg is an actor. Greg has a very good memory. And I would ask him to dig back into his memory. And he would do these conversations as clearly as he could remember them. And he knows Tommy so well that he could get those Tommytastic little grammatical flubs. I did very little of the dialogue. It kind of came out of Greg as he remembered the tenor of his conversations. That’s how it was recorded. And that’s how we transcribed it.

Correspondent: Was there any severe trauma, Greg, in this sense memory?

Sestero: Yeah. Actually, that’s off to a very good start. I do have a very good memory for better or for worse.

Bissell: And you’ve taken a lot of notes over the years.

Sestero: Yeah. And with Tommy, he’s so unique that you don’t really forget. As you can tell with the movie. People quote it all the time. You don’t really forget the way he speaks. There’s a very signature way of saying things. And it was such an unforgettable experience that I just remembered almost everything. And it came to me very quickly. I told stories about my experience to many people. So they were very vivid. Very clear in my memory. And the dialogue — I read excerpts of it to Tommy. Chapter Four. “Tommy’s Planet.” And he was shocked. He’s like, “My God! That’s exactly what happened. You remembered exactly what I say. Good job.”

Bissell: (laughs) You have to say it like he would say it.

Sestero: (in Wiseau voice) “My God! Good job!”

Correspondent: So he was consulted for all of the dialogue in this. I mean, he is a control freak, from what I gather.

Sestero: Yeah. I went over a lot of things with him about his past. And I traveled with him and I had gone to the places that I spoke about in the book. And he was very clear on stuff that he was comfortable with me putting in. His background, his retail career in San Francisco. But I knew he wouldn’t want me to talk about certain things. And I left that up to him. And I cut those things out. And the dialogue. Yeah. That’s the way he speaks. Basically verbatim. Especially when I traveled with him when I was writing the book on tour. And I was interviewing him. And it reconnected me with the way he talked. So a lot of that dialogue is straight out of how it happened.

Bissell: You also note that in the film, the film is a constant recycling of the same six or seven pieces of language. And when I’ve interviewed Tommy, he says those things. He wrote them. He says them. They kick around in his head. And so one of the real pleasures was, as Greg was remembering back and recreating these conversations, I would notice that those phrases would slip in. And I was like, the great thing I like about it is that a real avid Room fan will be reading these pre-Room scenes. And then suddenly boom! There’s a phrase from the movie. You’re like, “Oh my god!” Like when he asks Greg about how to get into SAG, he’s like, “Well like now that you are expert, how do you get into the SAG?” And then in the film, he’s like, “It seems to me that you are the expert, Mark!”

Sestero: Yeah. You can’t invent stuff with Tommy. He’s just this character that exists. So to do him justice, you need to quote him verbatim. And that was my goal with it. Is to be as exact as possible.

Correspondent: Has the Wiseau vernacular helped you in the course of your adult life? Has it allowed you to, I suppose, be more forthcoming in certain ways? When talking with family or friends or therapists?

Sestero: Yeah. It definitely has.

Correspondent: Do you have any examples you can offer? I mean, if you go to sleep at night, do you sometimes hear that Balkan voice lulling you?

Sestero: Yeah.

Bissell: (laughs)

Correspondent: Encouraging certain nocturnal dreams and associated emissions?

Sestero: Definitely nocturnal. I do have many laughs about what Tommy would say in this moment. And I’ll even think like him sometimes.

Correspondent: Think like him?

Sestero: Yeah. Like what would he say? There’s one thing I really find. He’s always going. He’s always grabbing things and bringing things places. And I’d just be standing there and watching him. He’d be like, “My god, do something! Don’t be Statue of Liberty!” And so I’ve noticed myself carrying posters and getting really busy during this time. When somebody’s standing there. “Will you help me?” And I’ll think, I say, “Could you help me?” But Tommy would be like, “My god! Do something!” So it’s funny. I’ve understood him a lot more in the last few years what he says. But the way he communicates is so funny that it just makes him the character that he is.

Correspondent: One thing I didn’t know until I read this book was that The Talented Mr. Ripley was a huge influence on The Room, which I had no idea about and which makes complete sense in hindsight.

Bissell: It’s the source text.

Correspondent: The source text. Tommy and Greg. Tom and Dickie. And as you point out, it gave you the flu when you watched it the first time, without Tommy, for about two weeks.

Sestero: Yeah.

Correspondent: This was fascinating to me. I’m wondering if you have actually gone back to the original source, Patricia Highsmith, and tried to mine those novels for deeper insights about Tommy or your own life or how you became friends with him and all that.

Sestero: Yeah. I actually started reading — I’ve read the entire Ripley series. Yeah, they’re very similar characters in ways. The difference is, I think, that Tommy, deep down, he’s a genuine person. He’s charismatic. While Tom Ripley has a dark streak. He’s just not comfortable with himself. So there are fine lines of the way they operated. But it’s amazing.

Bissell: It’s the longing.

Sestero: Yeah. And it’s the core. When Tommy watched The Talented Mr. Ripley, what it did to him, how it really got a rise out of him like no other movie that I’d seen when I’d watched it. Like we watched Fight Club and he’s like, “My god! This is so boring.”

Correspondent: (laughs) He was bored by Fight Club?

Sestero: Yeah, I know, right? He was like, “I do better acting in class.”

Correspondent: Wow. Even with Meat Loaf and the cool editing?

Sestero: Fight Club‘s one of my favorite movies. But The Talented Mr. Ripley is — it has that element. He lit up. And that’s what he wanted to make.

Bissell: When Greg revealed that to me, and I didn’t know that until it actually came out in our interviews, I was like, “Stop the fucking tape.” And we actually stopped the tape. And we sat there and we talked through all of the correspondences. You and I just started bringing up things from the movie.

Sestero: It all started to happen!

Bissell: It all started making sense. Oh my god!

Sestero: Peter. There’s a character named Peter in The Talented Mr. Ripley. Matt Damon. It’s all his fault. Mark Damon. The all-American guy.

Bissell: And we both read Strangers on a Train when we were working on this book. That’s the reason we talked about that book a lot. So there’s a weird Highsmithian quality.

Sestero: Yeah.

Correspondent: Except there have been no murders thankfully.

Bissell: (laughs)

Correspondent: Unless you did a criss-cross thing.

Bissell: Well, there was that one vagrant you and I hunted for sport.

Correspondent: Greg, it seems to me that with this Los Angeles apartment, the repeat playback of Tommy’s audition tape, the phone calls when you worked as a salesman at Armani Exchange, that you were either remarkably patient with Tommy or, well, you enjoyed being walked over. And I was really curious about this. I mean, even accounting for the whimsical follies of being a young man, what do you think kept you coming back to Tommy Wiseau? I mean, what was it? Was he just extraordinarily charismatic? Or did you just overlook some of these qualities?

Sestero: Yeah, I think youth obviously comes into play. But there’s just something about Tommy that was different. And I felt like an outcast with my family. And Tommy made me feel like I belonged to something. And I couldn’t really let go of the fact of the L.A. experience that I had when I first got there, the excitement of it and thinking that really I would have never had that. And even if that’s all it was, I never would have had that. And it was really because of him. So that bond really became strong. And it was really difficult. I mean, obviously, I thought about saying, “My god, I’ve got to just get out of this.” But anytime I tried to flee or tell Tommy what I thought or got emotional, and said those things, he would always retreat and come back and be like he didn’t mean to make me feel that way. So it was tough to leave somebody, especially in the book when he disappeared. When I saw him outside that acting class, just standing away from everybody, I felt for him. Because I felt the same way in a lot of ways. Except that I fit in more. But I understood what he was going through. So it’s hard to let someone float off into despair, knowing that you can make a difference. I always felt at the end of the day that I’d rather make a difference, to make someone feel better, than be self-aggrandizing. I guess this is all about being selfless than being selfish. I mean, obviously, I look crazy when you are able to look at the experience from the outside and see all these problems. It’s easy to just leave. But sometimes when you’re in it, you want to do what’s right hopefully and help that person.

Correspondent: Well, he probably gave you more approval than Robin Williams did on Patch Adams. Who knew that Tommy would have more solicitude than Robin Williams? Who I thought would exude that kind of thing being a wild and crazy guy from San Francisco.

Sestero: Yeah. Tommy’s a force and he challenged me to say, “Don’t be a chicken. Go for what you want to accomplish.” And I just never really forgot that.

Correspondent: Okay. I wanted to ask about the mysterious $6 million that financed The Room. There are allusions to a string of shops. The TSW Corporation so intrigued me that I actually did a business search at the California Secretary of State, finding nothing in relation to this.

Sestero: Really? (laughs)

Correspondent: I didn’t. So I’m wondering, Tom, what investigative acumen did you bring to this project? To really track down the Wiseau mystique? The unknown trail that people have been thinking about and conjuring up all sorts of theories about over these many years.

Bissell: Everything I know is in the book. And at a certain point, I have no idea how he amassed this fortune. I don’t think you really know either.

Sestero: I know he works around the clock. I know he had retail shops. I’d been there. I know he has those things. I know he owns a lot of real estate.

Bissell: He owns real estate.

Sestero: And that’s as far as it goes. I did research and interview people, but really I wanted him to tell his story and let the readers decide what was there.

Correspondent: Is there any way to get that video he sent to the insurance company? Because the way it was described was rather extraordinary.

Sestero: It was extraordinary.

Bissell: I’ve seen it.

Sestero: When Tom watched it…

Bissell: It’s incredible.

Sestero: …his reaction was that he put his hand up and he was just like, “Oh my god.”

Bissell: (laughs)

Sestero: What have I gotten myself into?

Correspondent: Basically, just to tell our listeners, he had all this classical music over it apparently and also he recruited people to say good things about Tommy. So that he could get the insurance money. (laughs)

Bissell: And there are these really mournful shots of these burned blue jeans, scorched.

Correspondent: Blue jeans? Really? (laughs)

Sestero: They actually didn’t even look that bad.

Correspondent: (laughs) The insurance company went for this?

Bissell: I don’t know.

Sestero: I don’t know.

Bissell: All we have is the tape.

Sestero: He’s a relentless retail guy. In fact, right now, he’s even designing an underwear line and a jeans line.

Correspondent: Is he really?

Sestero: He’s going all out.

Correspondent: Are you going to be one of his models?

Sestero: No. I’ll delegate that to somebody else.

Correspondent: Tom, do you need some additional income?

Bissell: I don’t think the world needs to see that.

Sestero: (laughs)

Correspondent: Okay.

Bissell: But I will say the line that I’m happiest with in this book is: “In discussing Tommy’s background, the simplest answer is the right answer. But with Tommy, there doesn’t seem to be a simplest answer.” That’s the astounding thing about him.

Sestero: Yeah. You think you know something. And then there’s just a trail of mystery that you’re lead down. And after knowing him for fifteen years, there’s still a lot left to know.

Correspondent: But if you think about it, the creative financing that he brought to The Room is really no different than the creative financing that is behind most Hollywood projects.

Sestero: That’s true.

Bissell: (laughs)

Correspondent: I’m wondering if, for some reason, he inhabited that same kind of blind reckless instinct that we usually associate with Hollywood producers who hope someone else can cook the books. And really that’s why he was able to get The Room made. Just because that’s the way it is in L.A.

Bissell: It seems like he read a how to make a movie book, but skipped every other paragraph. Because some things he obviously did right. One of his quotes is “How they do so in Hollywood. We no different from big studio.” So he clearly believed he was doing things according to studio procedures.

Correspondent: He was following some of the guidelines.

Sestero: Yeah. His interpretation for The Room was that he was doing it like the big sharks. The billboard, the equipment, the green screen. He thought that’s how a high-end Hollywood production does their movie.

Correspondent: One of the most frightening elements of The Room, which I really must talk to you gentlemen about just to clarify this, is Tommy Wiseau’s ass. It is there. It reportedly scared the editor’s wife. It is covered during the love scenes and yet we have this one Brad Pitt-like moment when he’s out of bed. And as the book puts it, “I’ve never seen anyone more comfortable naked around people who resented him.” But this still doesn’t explain something, which I had hoped to get from the book. Maybe you guys can answer. Which was the relentless soundtrack of groans and thrusting that are over all of these love scenes. They’re relentlessly noisy. And I’m wondering if there’s something about Tommy Wiseau’s relationship with his ass contributed to the kind of noise factor in these particular scenes, to say nothing of the fact that eleven minutes of the film is composed of love scenes and all that.

Bissell: (to Sestero) You had to record those groan tracks.

Correspondent: You were actually the groaner?!?

Bissell: You can hear Greg in one of the groan scenes going “Ohhhhhhhhhhh!!!!”

Sestero: Yeah, I had to sit in a video booth and do those while watching it. And I just thought, “My god. This is just painful.” And I thought, okay, let’s make it easy. Again, I didn’t think anyone would see it. So I did that. And it came out terrible. But Tommy did the same thing. I think with Tommy, he’s proud of his rear end. And that’s great. But he was trying to create a leading man moment for himself and felt good about it and he believed. He has to show his ass in this movie or it will not sell. So that’s what made him decide. He was laying on the ground inside Birns & Saywer, wondering if he should do it. And he’s like, “You know what? I have to.”

Correspondent: And it was not even a closed set. That’s what’s even more fascinating about that.

Bissell: He opened the set.

Correspondent: He opened the set. Wow. But that’s the other thing! Could he just not remember his groans? Much as he could not remember his lines?

Sestero: Well, with the groans, I think sometimes they do do those little things in post to fill them in. But his groans went really too far. Which I think make those scenes even more fun.

Correspondent: (laughs) Oh yeah? There’s groan outtakes.

Sestero: Yeah.

Bissell: How long is that first sex scene? It’s three and a half minutes.

Sestero: So long.

Correspondent: I know.

Sestero: It was actually even longer in the rough cut. It was like a music video. It just kept going on and on.

Correspondent: But he had to find something. A song that would last just as long.

Sestero: Exactly.

Correspondent: He couldn’t find a seven minute song that would work.

Sestero: He actually wanted to have one of Bon Jovi’s songs.

Bissell: “Always.”

Sestero: “Always.” To be there. And I don’t think Bon Jovi went for it.

(Loops for this program provided by oryan55, cork27, EOS, camzee, and supertex.)

The Bat Segundo Show #518: Greg Sestero and Tom Bissell (Download MP3)