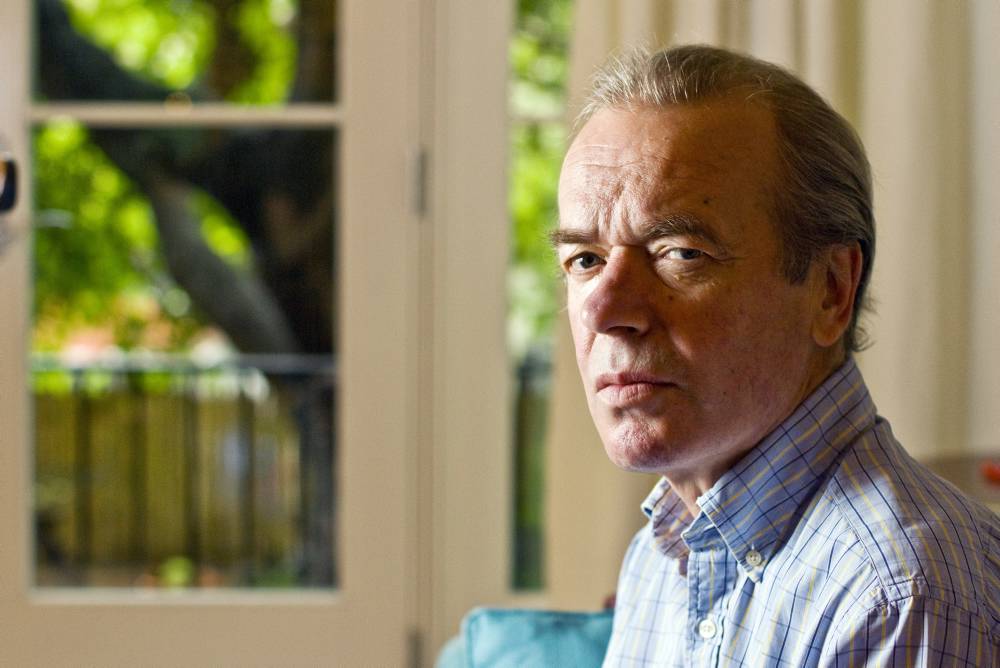

Martin Amis is most recently the author of Lionel Asbo. He previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #101.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Seeking the filter of considered thought.

Author: Martin Amis

Subjects Discussed: How smoking prohibitions curtail sociopaths, Katie Price as fictional inspiration, reading the collected works of Jordan, whether Amis should be writing about the working class, class anxiety, living with a Welsh coal miner’s family, Amis’s views on class disappearing in England, the London riots, the 1992 Los Angeles riots, people shooting at each other during Black Friday, income inequality, physical deterioration in Amis’s novels, Lindsay Anderson’s if…, the male climacteric, Amis’s tendency to introduce incest with legal and moral codex, researching incest, “yokel wisdom,” New Labour and education, opportunism and rioting, Occupy Wall Street, police brutality, whether fiction can ever rectify social ills, Swift’s A Modest Proposal, Dickens, the video game medium, clarifying Amis’s stance and false rumors of shame about Invasion of the Space Invaders, being befuddled by remotes, addiction, being a Luddite, representing the present in fiction without including smartphones, going back in time as a novelist, Money and Amis’s lack of interest in New York, when nonfiction serves as a muse for fiction, pornography, masturbation, young people and sex, The Pregnant Widow, not fully understanding world events when writing The Second Plane, the massacre of the Sunni Muslims in Syria, social media, the camera as world policeman, Nabokov’s slogans, what provoked Amis’s impetuous words in a 2006 interview, Amis’s problematic remarks in interviews, lacking a filter, and writing as the ultimate intercession.

FULL TRANSCRIPT:

Correspondent: I wanted to actually start this conversation with smoking. I know that this an interest of yours, but it is interesting. Because I noticed something fascinating about Lionel Asbo. Here’s a guy who has no problem muttering melee-inspiring words at a wedding, right? He’s also a guy who has no problem feeding Tabasco and lager to his pit bulls. And yet, rather interestingly, when it comes to this hotel that he stays in, where everything is nonsmoking, he does, in fact, go out every fifteen to twenty minutes for his cigarette. It’s this rare moment of civilization. That he’s actually polite. Which is very surprising, in light of the fact that he’s got this considerable fortune. And I said to myself, “Well, that is uncanny.” Because in light of your real-life crack-smoking inspiration, I’m not sure if he would do that. But then I thought to myself, well, in The Pregnant Widow, there’s this very interesting moment where you talk about how people are not allowed to smoke in dreams. There’s this interesting idea. And I’m wondering perhaps this is something of a dream. I was wondering if this came from a need to give Lionel some redeeming quality or some relatable quality. How did this happen?

Amis: Well, he’s appalled to find that the whole hotel is nonsmoking. But you can’t defy that kind of rule.

Correspondent: Even with money?

Amis: No. I mean, if you’re in a grand hotel and you don’t want to get chucked out. I mean, I think even the most fanatical smokers have accepted that. That they can’t smoke indoors anymore.

Correspondent: When did you finally give up?

Amis: Give up?

Correspondent: Yeah. I mean, give up the fight trying to smoke indoors. There’s nothing you can really do, right?

Amis: No. There’s nothing you can do. And I don’t smoke indoors here. It’s something you just — it’s a battle you’re resigned to losing.

Correspondent: Yeah. Even the great sociopath can’t smoke inside of a hotel.

Amis: No.

Correspondent: Well, in terms of other real-life inspiration, I do have to talk about Threnody, who of course is inspired by Jordan, Katie Price. You once described her as “two bags of silicone.” I know that you actually read a number of her books as research. And I’m wondering. Why couldn’t you ignore the collected works of Jordan? Because I know that you have a number of outside friends who take you into intriguing places and you have this incredible real world research that you can do. What did the Jordan books offer that your various peregrinations of a clandestine nature could not?

Correspondent: Well, in terms of other real-life inspiration, I do have to talk about Threnody, who of course is inspired by Jordan, Katie Price. You once described her as “two bags of silicone.” I know that you actually read a number of her books as research. And I’m wondering. Why couldn’t you ignore the collected works of Jordan? Because I know that you have a number of outside friends who take you into intriguing places and you have this incredible real world research that you can do. What did the Jordan books offer that your various peregrinations of a clandestine nature could not?

Amis: I came to admire Katie Price, having read those books, simply because she’s a mother of three children and one of them has great problems. And she’s a brave and dedicated mother. And my opinion of her went up. By the way, the character Threnody is not based on Katie Price. She’s a Katie Price wannabe.

Correspondent: I see.

Amis: The figure who is based on Katie Price is called Danube. I thought she had to be the name of a river.

Correspondent: Sure.

Amis: And I rejected Volga as being a bit too obvious. But I read those books really for the kind of furniture and the background of what those people get up to. She goes to the VIP enclosure of the ELLE Style Awards. I mean, you can’t make that kind of thing up. Because you just don’t know the vocabulary of that weird, semi-celebrity life. So with some characters, it’s best not to go too close. To leave your imagination some room. So I didn’t want to mingle with real-life Threnodies. I wanted to dream her up.

Correspondent: I see. So the book serves as this protective buffer. So that you don’t have to deal with a certain class of people.

Amis: Well, they complained in England that I shouldn’t be writing about the working classes, which I’ve been doing for forty years without comment or challenge anyway. So there’s a new anxiety that the working classes ought to be reghettoized in fiction. Which I think is a sort of contemptible notion. Is one only allowed to write about one’s own class? I’ve written about the royal family in fiction and no one objected to that. It’s pusillanimous and ridiculous to say that. I think there are no entry signs in fiction. You can go anywhere you like.

Correspondent: Yes. Well, I saw this very interesting three part BBC4 documentary, in which it covered you in the third part. And Hari Kunzru was interviewed. And he suggested that this tension between the upper class and the lower class in your books was, in some sense, a kind of class anxiety. That the sort of rough, tough working-class yob is going to go and grab the property or the livelihood or the affluence of the top-tier classes. And I was wondering what your thoughts are on this. Is this a tension of extremes? Do you have any fears of people like Keith Talent or Lionel Asbo in this book?

Amis: No. It’s completely unanxious. In fact, it’s celebratory. What attracts me to that milieu is how rich it is. It’s full of wit and poetry that I don’t think people understand. This is just as much a part of that life as of any other. And when I talk to people who would be dismissed in those class terms, I’m astounded by how intelligent they are and how witty and how original. No, it’s affectionate and admiring. I’ve always had this vein in my life. Right from childhood. My parents parked the children in the family of a working-class Welsh coal miner and his wife. And I took to it very much. I always responded to it and enjoyed it. And they think because you’ve been to Oxford and you’ve got a poncy accent that you must be sneering at these people. You couldn’t. Who could write a novel with that kind of emotion in the forefront? Novels are all about — it’s crude, but it’s a loving form. And that’s what I feel for all my characters.

Correspondent: You love them? Because you cannot deny that there is often a monstrous element to these figures. And in writing and coming to terms to some truth, with that monstrous and vile and scabrous quality, you’re going to have to feel some fear or some anxiety, I would think, as a writer.

Amis: No. Because who was it who said that the covers of a novel are like the bars of a cage. And you can admire the tiger or the crocodile without fear. And the novel domesticates those atavistic passions. And this guy’s a dangerous guy in my Lionel Asbo. But I think he’s quite comprehensively balanced by Desmond, his nephew, who is rather implausibly generous and empathetic and altruistic. So the two sides are there. Class disappeared in England in the ’80s, really. Margaret Thatcher, for all her sins, detached the Conservative Party from the ruling classes.

Correspondent: Class disappeared? I don’t know. I saw the London riots and that seemed very much a class struggle.

Amis: Well, I mean, of course, it’s always there. And the snobbery is still there. But they hardly dare say, they hardly dare confess to it anymore. And it was a defining feeling in the ’70s and ’80s, and earlier of course, that you were being sneered at from higher up and challenged from lower down. And the novel I wrote about that was published in ’78, called Success. But that’s a thing of another generation now.

Correspondent: How would you say class has changed from the ’70s and ’80s to now in England? And how would you say this has affected your novel writing?

Amis: It’s more — the strata are different now. It used to be upper, middle, and lower. And now it’s — the upper classes are still in its huge houses and all the rest. But the middle class has hugely expanded. And there’s now what some people call the underclass. Or the old word for it is the residuum. And that’s there. And that’s what you saw during the rioting. Although it’s a funny kind of riot when the rioters go and try on various sizes of sneaker in the shops they’re looting. Although you may notice that the only shop that wasn’t looted was the bookstore in that particular strip.

Correspondent: Well, you can say the same thing about the L.A. riots from fifteen, twenty years before. It’s the same situation. Although that doesn’t take away the fact that there are very deep tensions. There’s deep tension, of course, between the classes and race and so forth. I mean, you’re always going to have a little bit of that capitalistic element or that materialistic element. Hell, even with Black Friday, we were joking here in America last time. Because it was so severe that you have to now bring home defense in order to get that deal. I mean, it was really ridiculous. People were getting shot. It’s both utterly depressing and utterly funny at the same time. But at the same time, how do we make sense of this? Or does the fiction that you write permit one to, I suppose, embrace both feelings and feel the sense of seriousness and humor at the same time to try to contend with what this exactly means?

Amis: Yeah. Such questions as “What does this mean?” don’t really come up when you’re writing a novel. And you ask, “What are you getting at? And what are you actually saying?” To which the only answer is: I’m saying the novel, all 270 pages of it, it’s not reducible to a slogan that you put on a T-shirt. But I think a couple of years later, you see certain connections and certain relationships to real life and how you feel about it. And I think what I’m writing about when I do take on this milieu is inequality. Now as you know, the whole momentum of the mid-century and beyond was for greater equality. Now that, both here and in England, inequality is now back to post-World War I levels. The difference between the rich and the poor has increased very sharply all over again. And the reversal of that tendency was widely noticed. And I think that it’s a great evil. And I think it’s very demoralizing for a society with those levels of inequality. And I think it goes without saying that you’re sort of, in as much as a novel can strike a blow or make a claim, that you’re pointing to the shameful and ridiculous aspects of inequality.

Correspondent: Sure. Let’s shift to the notion of physical decay, which I’ve been long wanting to talk to you about. It’s this especially prominent quality in your first four novels, of course. And then it gets into outright topographical territory with John Self’s Upper West Side. And then it’s become less tangible in these more recent books. It’s more observational or reflective in some sense. And let me give you some specific examples. I think of the early line in The Pregnant Widow. You have Keith Nearing. He’s in his fifties. And he’s finding “something unprecedentedly awful” every time he visits the mirror. And then, much later in the book, you have Keith note that his body in the mirror is “realer,” even though his body is “reduced to two dimensions. Without depth and without time.” So in Lionel Asbo, you have this situation with Granny Grace. And she actually has a physical decline. But in this, what seemed to me more deeply felt was the fact that she could not do the cryptic crossword. And I wanted to ask you. Why do you think you pushed this idea of physical deterioration into something where it’s in a mirror or we’re concentrating on mental faculties? It’s interesting that you’re almost doing this in reverse, it would seem. Because one would think that the young novelist would be more concerned with physical vitality and that the older novelist would be more concerned with physical deterioration. With you, it almost seems inverse here. So I was curious about this.

Amis: Well, I think there’s a bit about it in The Pregnant Widow. When you’re young, you have what they call nostalgie de la boue. You’re homesick for the mud. You’re tied up with your bodily emanations in a kind of childish way. Then a lot of self-disgust is generated by that. Remember that, in the film if…, these schoolboys are going around. And one of them is breathing into his hand and saying, “My whole body’s rotting.” And he’s nineteen. Then it does live and you’re much more at home with your body during your thirties and forties. And then suddenly it becomes a preoccupation again, as you see…

Correspondent: That wonderful thing called the male climacteric.

Amis: Yes. It’s the decline of your powers. And no one likes that. But I think, whatever else you can say about it, it’s a great subject. And it’s possible there’s a lot of humor in it and some dreadful ironies. And it’s witty. You know, it’s not a blind insensate force. It tells you who you are. And you’re in the process of completing your reality, and this is another part of it.

Correspondent: Do you think physical deterioration is the best way for you, as a novelist, to really understand the physicality of these characters? That if you know how they’re rotting or how they think that they’re rotting, you suddenly, in your mind’s eye, immediately know, “Well, I know exactly how they move. I know exactly how they look. I know exactly how they act.” What of this?

Amis: Yeah. Well, you’re always trying to get in there. Into the hearts and souls and minds of your characters. And you want to know how they dream. And self-image is quite a good way to internalize these characters. What do they think when they look in the mirror? So that’s part of what one does automatically.

Correspondent: Well, in Success, you have this section where Gregory writes, “Of course, it’s all nonsense about ‘incest,’ you know.” And then he proceeds to cite a number of legal precedents to basically back up his reason for his incestuous relationship. In Yellow Dog, you have this issue about the sentiments where “some fathers really believe that incest is ‘natural.'” You have that. And there’s also this business of there never having been “a human society that doesn’t observe incest taboos.” In Lionel Asbo, we see, of course, another incestuous relationship. Des has to write into a newspaper to ask himself about the question of whether this is legal or right or not. It is interesting to me that nearly every time incest pops up into your work, there’s this need to confirm it against some sort of legal precedent or some sort of confirmation. You can’t just have characters getting into an incestuous relationship. You have to actually back it up with what the moral code is or what the legal code is. Why can’t you just have the reader decide whether it’s bad or not? I’m curious about this.

Amis: Well, Desmond is fifteen. And the only person he could ask for advice about these things is his grandmother. And he can’t ask her. In fact, when he does, she says, “It’s only a misdemeanor just because you’re not yet sixteen.”

Correspondent: The fact of the matter is that she uses the word “misdemeanor.” Another legal term. Which is what’s really curious about this.

Amis: Yeah. Well, I mean, it seems to me a realistic point. That he has no way of finding out. And Diston, the imaginary borough of Southeast London where the novel is largely set, is full of incest, as well as other weird demographic oddities, like life expectancy is 58 and women have five or six or seven children. It’s meant to be a world where these certainties are no longer so.

Correspondent: How much research into incest have you done? How many books on incest have you read?

Amis: For Yellow Dog, I read a book called Father-Daughter Incest. It horrifies me. Fred West, the murderer who killed my cousin, I read a lot about him too. His axiom with all his many children was — he used to tell his daughters, “Your first child ought to be your dad’s.” And you can imagine some sort of yokel rhyme saying “Unless first child by father be.” And it’s a sort of yokel wisdom. And it’s such an appalling idea. There’s a good reason why it’s taboo. It’s because nature doesn’t like it. My mother’s parents were first cousins. And my wife said to me quite recently, a few years ago when I told her this, she said, “You never told me!” And I said, “I told you a long time ago. What does it matter? It’s not all my relations are cousins, which can lead to great trouble.” And then we were in Barbados and we pulled up to ask directions in the street. And a guy turned around. He had a handkerchief in his mouth. And he was sort of burbling and was obviously deeply retarded. And as we drove away, my wife grew thoughtful and said, “You know, you really ought to have told me about your mother’s parents.” As if idiocy is waiting to swoop even now. So now that you’ve pointed this out to me, I see that it is a theme that occurs. But I don’t think I have any deep feelings about it other than it’s an unnatural and criminal activity. It’s weird that in all the prohibitions about consanguinity and relationships between related people in the Bible and I think even in the Koran, there’s no mention of father/daughter. I think perhaps because it was so common and has been so common in human history that we look the other way.

Correspondent: You mention “yokel wisdom.” And we were talking earlier about how the working class — well, a lot of them are smart and so forth. So how do you reconcile this notion of class and intelligence?

Amis: It’s partly what the novel is about. It’s about intelligence and about the uses of it. And the big contrast between Desmond, who has a great thirst for cultivating his intelligence, and Lionel, who is clearly quite bright, but is anti-intelligence and is stupid on purpose much of the time.

Correspondent: He makes a decision to be stupid, you say?

Amis: Well, Desmond says, “He gives being stupid a lot of very intelligent thought.” To come up with the stupidest thing you can possibly do.

Correspondent: But maybe Desmond is trying to figure out why he’s like this, why he decides to be like this, why he doesn’t apply himself.

Amis: Yeah. He is. But I go along with, politically and in my life, the New Labour slogan “Education, education, education.” And it’s something I deeply feel, that there’s a lot of undeveloped intelligence down there. And the people feel so neglected and excluded that they think, “Oh, to hell with it. I’m going to be stupid. I’ll show them. I’ll be even stupider than they think I am.” They’re not stupid.

Correspondent: Do you think stupidity motivated something like the London riots? Or was that desperation?

Amis: That was pure opportunism.

Correspondent: Pure opportunism?

Amis: Yeah.

Correspondent: Wow.

Amis: Opportunism. I mean, it’s almost always sparked by a bit of police brutality or overreaction. And they shot a guy who was clearly a practicing criminal in Totland. This is then the signal or the excuse, the pretext for an explosion of rage.

Correspondent: What then would be an acceptable response? Because we’re seeing, for example, with Occupy Wall Street, that movement is responded to with police brutality. You’ve got infiltrators who are then splitting up the crowd. It’s the same cycle of history that we saw in the ’60s. It’s happening again. It’s going to happen again. And if the income inequality, as we established earlier, has moved to post-World War I levels, what to you would be an acceptable form of responding to a gross inequity?

Amis: Well, for me, it would be writing about it. Either as a journalist or as a novelist. Although the novelist is always three years behind the journalist. Because you have to soak it up and absorb it and go through these weird subconscious processes before you can address it in fiction. But I thought the Occupy movement was very intelligent and curiously so postmodern in its avoidance of actual concrete demands. It was just a civilized expression of disaffection with the system.

Correspondent: It proved, I think, that an amorphous general message is what will rally a number of people together to actually protest for something.

Amis: Yeah. And not factionalism. And not competing ideologies. I very much responded to the fact that they didn’t come out with a program or a manifesto. That it was just something a bit more subliminal than that. Whether it can sustain itself looks doubtful now. But you do tend to need these slogans and rallying points. But I very much respected it while it was going on.

Correspondent: To jump back to your earlier point about writing being an answer to correct gross inequities or to remedy problems or social ills, I mean, let’s look at your work. We have probably the two most prominent examples. It would be House of Meetings and Time’s Arrow to reckon with a serious — in both cases, genocide. But I’m wondering though if that’s really what the novel should do or whether that can really have the same kind of response that, say, Shostakovitch’s symphonies did. I mean, the novel is now so marginalized in comparison to other forms. The movie, television, the video game, and so forth. I’m wondering if you really can, in fact, have that when, of course, we are now living with the Peyton Place of our time, Fifty Shades of Grey, right?

Amis: But what’s your…

Correspondent: My point is: how can the novel respond and rectify social ills when it is, in fact, so marginalized and when, in fat, it could be argued that the novel’s purpose is not necessarily to be in that didactic mode?

Amis: Well, I don’t think any novel has ever rectified anything. A novel really asserts nothing. It used to be said that satire was militant irony. That’s the distinction. That satire sets out to actually have an effect on society. But it hasn’t, has it? I mean, Swift’s A Modest Proposal was written after the Great Famine. Dickens’s attacks on Chancery and imprisonment for debt, which his own family suffered from — those abuses were over, more or less, when he wrote Little Dorritt and Bleak House. The novel doesn’t work like that. And I said “Education, education, education.” That’s what novels do. Not just on particular subjects like the gulag or the Holocaust. But a novel tries to expand the perceptual world of the reader. So that anyone who reads your book will, you hope, have a richer response to their everyday surroundings, will see the world a bit through new eyes and sort of alienized and see the strangeness of what is taken for granted and what is, in fact, ordinary. Ordinary people, I keep saying to myself, are really very strange. And I think that’s true of the whole furniture of our lives.

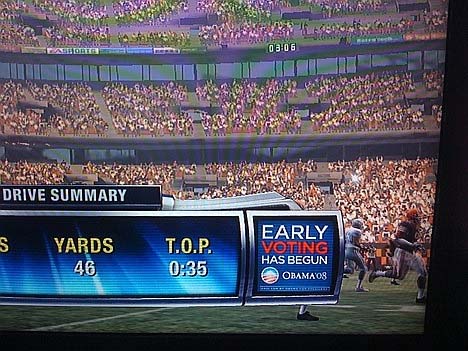

Correspondent: Sure. While we’re on the subject of mediums, I do have to ask you about something. I’d like to talk about a medium that has a $65 billion global value, a medium that, in fact, was used by President Obama in 2008 to advertise for his presidential campaign, a medium that your friend Salman Rushdie has claimed in an interview to be “something of an Angry Birds master.” That medium, of course, is the video game. I do know, and I have to ask you this, that you wrote a book about Space Invaders. And I’m wondering. I did notice you have your pinball machine still. Why are you reluctant to own up to this Space Invaders volume? I’ve been really curious. I mean, it’s hard to find. You don’t want to talk about it. But I’m telling you that, in this age when video games are so omnipresent and have arguably outsized the movie, why would you be loath to talk about it?

Amis: I’m not necessarily loath to talk about it. I’m no longer interested in it. But there it is on my “By the Same Author” page. I haven’t disowned it.

Correspondent: But you haven’t exactly welcomed it back into print.

Amis: It hasn’t come up. I think in Italy, they’ll redo it. But that generation of games, that’s gone.

Correspondent: Not on the phones.

Amis: Not on the…?

Correspondent: Yeah. You can play Space Invaders on a phone.

Amis: Can you?

Correspondent: You can play Pac-Man on a phone. In fact, the interesting thing about some of these games is that they’re so universal and the technology is in a compact form. So you can actually use them. But what’s also impressive is, as I said, Obama actually advertised in game for 18 games in 2008 to reach voters. That’s how significant this is. And that’s why I’m curious why you have been, at least from what I’ve seen, reticent to grapple with the fact that video games are a massive part of our culture.

Amis: It’s because I’ve been left behind by all that. It’s all I can do to get a picture upon our digital TV.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Amis: I have to shout for one of my children to come and help me. I’m sort of all thumbs with all that right now and no longer interested in those slightly onanistic, solitary pursuits. But I’m as aware as everyone else is that that kind of — and I saw it with all my children that they went through years of not really wanting to do anything else. And I know how addictive they are.

Correspondent: They are very addictive. I had to uninstall some myself. That’s how bad they are. I had to read. When was the last time you played Space Invaders out of curiosity?

Amis: Not for twenty-five years. But what seems to be very addictive, my daughters admit to this, is that you do the first level and then you get on to the next level. And that kind of incremental building of skills to get to a new phase of the machine seems to be very deeply wired into us all.

Correspondent: So the addictive qualities really are why you have stayed away. Because you know that if you were to touch it again, you would actually get sucked in?

Amis: I don’t think so. I think I’m too Luddite now. I’m sort of anti-machines. And I get into a fury with things that don’t respond to what seems to me to be very simple instructions. Like the remote buttons on your TV. They’ve succumbed to what they call feature creep, where they just pile on the extras until it’s unusable by someone who isn’t prepared to really enter into it. So that part of my life is just sort of dead. And I couldn’t imagine getting interested, let alone addicted, to that anymore.

Correspondent: But what about, for example, Lionel Asbo? You conveniently have an area of Diston where somehow there are no iPhones really. There’s a Mac at the very beginning, but the sounds that we hear are natural shouts, as you are careful to note. The book goes into 2013 and really doesn’t wrestle with the fact that, if you go outside, people are looking down at their phones. They’re taking pictures of everything. They’re documenting every minutiae. And I’m wondering if you’re ever going to grapple with the reality of social media and just the sheer compact technological hold, the hold that compact technology has upon our lives.

Amis: My father said at one point. He said the reason you writers hate younger writers is that younger writers are telling them — they’re saying to the older writer, “It’s not like that anymore. It’s like this.” And it’s painful not to be on the crest of modernity as you were when you were younger. It’s not that you’re hankering for anything that’s gone. It’s not a reactionary things. It’s a helpless exclusion, really, from things you no longer understand and don’t want to make the effort to understand. Though I’m sure there are many able writers who are going to do what is there to be done with that subject, social media. But it’s not me.

Correspondent: You’re on safe ground when you go back to 1970 or, with your next book that you’re working on, back to the 1940s. Is going back in time your solution to this problem? I mean, the bona-fide literary high standards type will basically say, “Well, it’s the writer’s duty to completely submerge himself into our present day culture. And if that means something as often obnoxious as social media or phones, that’s part of the deal, bub.”

Amis: Writers are under no obligation to do anything whatever. Nabokov said — well, he was perhaps a bit prescriptive the other way.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Amis: But he said, “I have absolutely no interest in these subjects that bubble up and in a year or two will resemble bloated topicalities.” He said, “My stuff is not interested in the spume on the surface of things.” That he’s looking underneath the surface. I don’t feel that I’m being at all neglectful in not finding out about social media. It’s not a subject that excites me.

Correspondent: What about — you did explore New York, especially areas of Manhattan in Money. You’re now in Brooklyn. Do you have any interest in exploring our interestingly gentrifying areas around here?

Amis: Beyond a certain point, I don’t think where you are makes much difference at all. We lived in Uruguay for three years in 2003 to 2006. And I was often asked if I intended to do anything with Uruguay in fiction. And I can imagine writing a paragraph or two about it. But you get the feeling, rightly or wrongly, that after a certain age that you’re locked into your own evolution as a writer and that the things that you’re writing about now have been gurgling away inside you for a long time. And the idea of having a sort of hectic response to what happened yesterday seems very odd to me now and distant from me.

Correspondent: What about nonfiction as an interesting muse? The obvious example is Koba the Dread upon House of Meetings. But actually there is one interesting line from Money, which I actually pinpointed to its source. And that is when John Self was on the phone and he says, “When I’m through with you, sunshine, they’ll be nothing left but a hank of hair and teeth.” Which, by the way, is similar to something Mailer said to a novelist: “When I’m through with you, they’ll be nothing left but a hank of hair and some fillings.” And actually I read The Moronic Inferno before talking with you, while I was rereading Money. I was reading a bunch of your books before we talked. And it was interesting how much your observations of America ended up in Money. And so this leads me to ask you. Does writing a nonfiction book or does submerging yourself in journalism allow you to test out themes? Or is this largely an accidental process where, through serendipity, certain kinds of observational bubbles float to the top for some future fiction project?

Amis: Well, the way it works, in my case at lest, is that if I’m going to go into a subject in fiction, I will often take it upon myself to write a longish bit of nonfiction about the subject. I did it with the Royal Family for Yellow Dog and also with the pornography industry for Yellow Dog. And I went to California. And I went around. And I wrote a long piece about it. And that gets you a certain distance. And then when you come to write the novel, you can actually — usually, because it’s been a year or two in the making — you find you’ve advanced your feelings about it and your conclusions about it. For instance, with pornography, it took me a long time to realize that it will never be mainstream until masturbation is mainstream.

Correspondent: We’re getting there. (laughs) I mean, all you have to do is go online and see what’s available pornographically. And there you have it.

Amis: But you’ve got a way to go before, before…

Correspondent: Before people are doing it in the streets.

Amis: Before masturbation is cool. So I always thought the resistance of women to pornography, which I would say is based on the fact that the act of procreation, which peoples the world. And this is women’s great power. Men don’t have it quite the same way. And they would always have great resistance to pornography because that act — so central to everything, our existence — is trivialized and denied significance. In fact, someone described pornography as hatred of significances. So that was the conclusion I reached in the novel. But it’s moved on. And I think the next phase is actually women ascending to it and then that’s when you have to — there are several things where you can no longer follow these things through. Because it’s just indecent at a certain age to be wondering about what young people think about when they think about sex. You just have to withdraw. And I’ve reached that point with sexuality. I don’t want to imagine what the sexuality of the young is like.

Correspondent: And yet there’s The Pregnant Widow. (laughs)

Amis: Yeah, but that was set in the past and was alert to these revolutions in consciousness that have taken place since then. You know, I talk to my grown-up daughter, who’s 36 now. And when she was in her twenties, she used to tell me about what the sexual circuit was like in those days. And we always had a very candid relationship.

Correspondent: Yeah. I was about to say.

Amis: But sometimes it would sort of chill me. And I just thought, “I don’t want to know anymore about it.”

Correspondent: So you encouraged an environment of candor as your kids were growing up.

Amis: Well, I didn’t raise my oldest daughter.

Correspondent: Sure.

Amis: But, yeah, I hope so with my boys and my girls, who are fifteen and thirteen right now. The younger girls. But they never tell you exactly what’s going on, your children. It’s always edited for…

Correspondent: For senior ears.

Amis: For senior ears. Yes.

Correspondent: I know you’ve got to jam, but I had one last quick question I have to ask. In light of what has happened with the Arab Spring — you got into a lot of trouble with some of your work in The Second Plane — would you amend or alter some of your statements in that book in light of what has happened? Especially with what’s been going on in Syria right now.

Amis: I think everyone is doing a lot of realigning in their own minds. My younger son has just finished his second degree on the Muslim Brotherhood. And he’s been studying that for two years and speaks Arabic and is going to go on studying it. And he said that all the people who were finishing their degrees when the Arab Spring hit were pretending that it hadn’t made any difference to their theses. But, in fact, he said, it’s had a disastrous effect on everything they’ve thought or written. Because it’s a new page in the history of those nations. I think Islaamism has become politicized and part of the mainstream in ways that weren’t clear to me a few years ago. I thought Hassan Nasrallah and certain very clever Islamists would make the shift to politics, even though they have sort of terroristic origins. As do…

Correspondent: Are you saying that you didn’t entirely understand that situation when you wrote The Second Plane?

Amis: Yeah. Who does?

Correspondent: Would you mollify your language if you were to have written that book today?

Amis: Yeah. I think so. I think I would have been less alarmist. But, I mean, with these very difficult questions, if you can just move the argument along even half an inch, it’s worth doing, I think. And it now looks — it looked as though Islamism was locked into a kind of agonistic relationship with the West, where it was going to be an eternal struggle that would never be resolved. And now it’s looking…

Correspondent: Well, 18,000 people in Syria. These Sunni Muslims who have been protesting against Bashar al-Assad. I mean, that’s pretty serious. Now we’re talking almost genocide figures. It’s very similar to the gassing of the Kurds and so forth. And that’s why I look to something like that. When you’re dealing with such a severe assault on human lives, then you have to recalibrate the needle and you also have to consider that what you say, well, maybe there’s another angle to this. You know what I mean?

Amis: Yeah. But what was that remark? 18,000?

Correspondent: 18,000 of the Sunni Muslims in Syria who have been executed under the regime. And, of course, you’ve got the deputy fleeing to Turkey as well. So it’s been an extremely terrible situation. Just from a human life standpoint. And when you say that Sunni Muslims are all out to get us and they want to kill other people’s lives, then I present this and I say, “Well, I can’t reconcile the two when 18,000 people have…”

Amis: Over what period?

Correspondent: Just recently. The Syria stuff that’s been going on. All the stuff that’s going on in Syria right now?

Amis: Yeah. I thought the figure was more like 3,000.

Correspondent: Well, it’s anywhere from 10 to 18, depending upon where — in fact, the 18,000 comes from the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. So it’s a pretty severe figure. But I’ve heard anywhere from 10 to 18. And I’ve been reading the BBC, the Guardian, stuff like that.

Amis: Right. Right.

Correspondent: The New York Times, I believe. So anyway…

Amis: I mean, the Syrian situation is very odd in that a minority leadership — just as Iraq was, the Sunnis were a minority there and the Alawites are a really small minority. And the sectarian war seems to be more or less launched already. So I think Syria is tremendously complicated and dreadful. And the difference is that we’re hearing about it every day. And when his father killed — what was it? 25,000 people in one action a generation ago — that news seeped out. But this is what social media give you. That’s the world policeman. It’s not America anymore. It’s the media.

Correspondent: The camera is the ultimate weapon these days.

Amis: Yeah, yeah.

Correspondent: Okay. So saying that you would have written it differently. Like that infamous 2006 interview you did. I mean, what accounts for some of these outlandish statements like “The Muslim community needs to self-police” and things like that. I mean, this is the kind of stuff that gets you into trouble. Is this a present emotional expression from you? And you need to dig deeper? I mean, what accounts for these kinds of statements?

Amis: It’s a slogan of Nabokov’s. “I think like a genius. I write like a distinguished man of letters. I talk like an idiot.”

Correspondent: (laughs)

Amis: And it should be stressed that these are remarks. Not considered words. Nothing you say in an interview is your last word. And also it was a question of timing. I gave that interview on the day when the plot was revealed to blow up 20 airliners in midair using liquids. And the lady who’d come from England to interview me in Long Island said that on the plane you weren’t allowed to bring books. And that was the lowest I’ve ever felt about this whatever it is. This antagonism that revealed itself on September the 11th. And I did actually think, just for a day or two, that we can’t win against these forces. And the idea of depriving a transatlantic passenger of a book.

Correspondent: That is pretty lame. Yeah.

Amis: Well, it seemed to me the triumph of the forces of pedantry and dogma and a defeat for all the things we hold dear. I remember Jeff Eugenides was staying at the time and I said, “I think we should collective punish. A bit of collective punishment.” He said, “No. But that’s going to turn the rest of them against us.” And I thought, “Oh yeah. A good point.” And what I said in that interview, I felt that day and ceased to feel it the next.

Correspondent: So it seems to me that basically you need to have a filter, whether it be through friends or whether it be through someone who’s around. The interview is actually problematic for you and this is what gets you into trouble. In that case, can I trust anything you’ve said in this particular conversation?

Amis: (laughs) Yes, you can. But people think you’re being provocative on purpose or confrontational on purpose. How can you do that? You just — I answer honestly and too candidly often. And the filter is considered thought. And that means writing. You don’t know what you think until you see what you say, see what you write. And that’s the intercession I probably need.

The Bat Segundo Show #480: Martin Amis II (Download MP3)

This text will be replaced

Both men had turned to screenwriting to stay afloat during the Great Depression. Both men had much to say about the traps and illusions of American life. But it would take longer for West to be reassessed and appreciated — in large part because he was arguably fiercer than Fitz with his fiction. He had his finger firmly on the troubling pulse of feral American life and he wasn’t afraid to use it with the other nine at his typewriter. In a short essay called “Some Notes on Violence,” West pointed to the idiomatic violence that had permeated every corner of printed media: “We did not start with the ideas of printing tales of violence. We now believe that we would be doing violence by suppressing them.” His razor-sharp satire featured philandering dwarves, skewered the hideous contradictions of gaudy Hollywood spectacle, and, in just one of many enthralling flashes of his grimly hilarious invention, depicted a dead horse serving as au courant decor at the bottom of a swimming pool. (In an age in which urine-drinking is prescribed as a COVID remedy and reality star Stephanie Matto makes $200,000 selling her farts in a jar, one wonders why the present fictional landscape doesn’t reflect our scabrous realities and why 85% of today’s gatekeepers are so hostile to such a necessary dialogue between fiction and life. But then this is the same universe in which Hanya Yanagihara’s excellent, quite readable, and wildly ambitious new novel, To Paradise,

Both men had turned to screenwriting to stay afloat during the Great Depression. Both men had much to say about the traps and illusions of American life. But it would take longer for West to be reassessed and appreciated — in large part because he was arguably fiercer than Fitz with his fiction. He had his finger firmly on the troubling pulse of feral American life and he wasn’t afraid to use it with the other nine at his typewriter. In a short essay called “Some Notes on Violence,” West pointed to the idiomatic violence that had permeated every corner of printed media: “We did not start with the ideas of printing tales of violence. We now believe that we would be doing violence by suppressing them.” His razor-sharp satire featured philandering dwarves, skewered the hideous contradictions of gaudy Hollywood spectacle, and, in just one of many enthralling flashes of his grimly hilarious invention, depicted a dead horse serving as au courant decor at the bottom of a swimming pool. (In an age in which urine-drinking is prescribed as a COVID remedy and reality star Stephanie Matto makes $200,000 selling her farts in a jar, one wonders why the present fictional landscape doesn’t reflect our scabrous realities and why 85% of today’s gatekeepers are so hostile to such a necessary dialogue between fiction and life. But then this is the same universe in which Hanya Yanagihara’s excellent, quite readable, and wildly ambitious new novel, To Paradise,

It has been five years since I last tendered any heartfelt words about 20th century fiction for the Modern Library Reading Challenge. An infernal yet magnificent Irish genius is to blame for the delay. Five years is frankly too damned long, especially if I hope to complete this massive and somewhat insane project before I croak my own answer to Joyce’s “Does nobody understand?” Frank Delaney’s

It has been five years since I last tendered any heartfelt words about 20th century fiction for the Modern Library Reading Challenge. An infernal yet magnificent Irish genius is to blame for the delay. Five years is frankly too damned long, especially if I hope to complete this massive and somewhat insane project before I croak my own answer to Joyce’s “Does nobody understand?” Frank Delaney’s

Weiner: I hope we talk about that.

Weiner: I hope we talk about that.