(This is the fifth entry in The Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge, an ambitious project to read and write about the Modern Library Nonfiction books from #100 to #1. There is also The Modern Library Reading Challenge, a fiction-based counterpart to this list. Previous entry: The Journalist and the Murderer.)

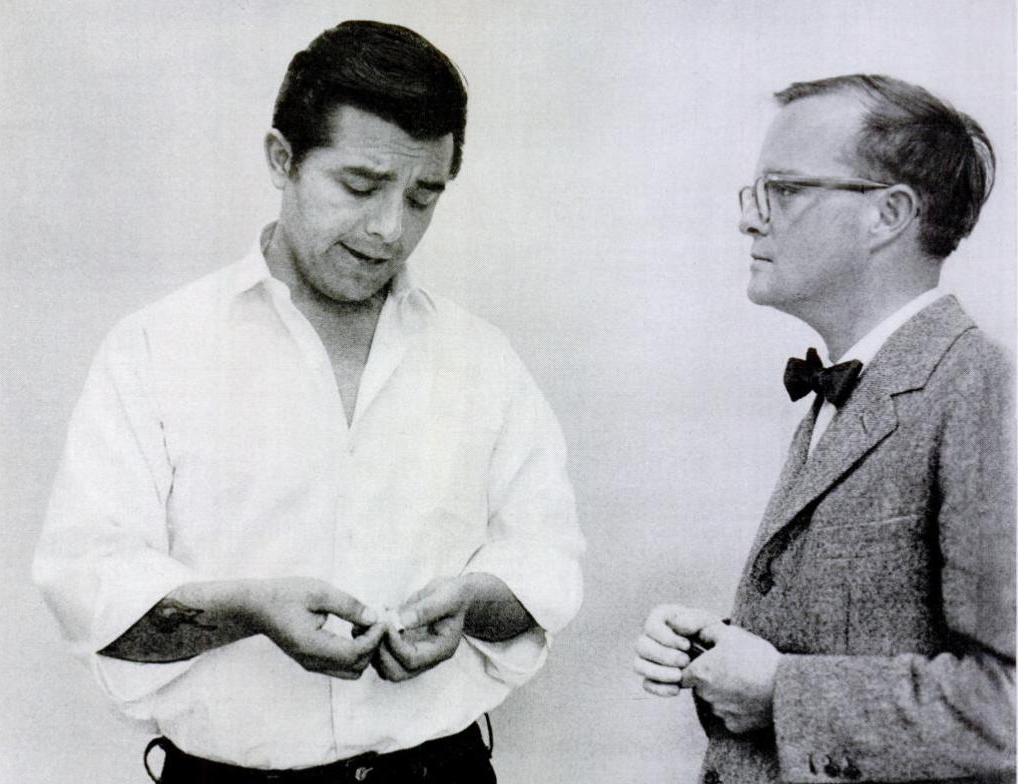

Truman Capote was a feverish liar and a frenzied opportunist from the first moment his high voice pierced the walls of a literary elite eager to filth up its antimacassars with gossip. He used his looks to present himself as a child prodigy, famously photographed in languorous repose by Harold Halma to incite intrigue and controversy. He claimed to win national awards for his high school writing that no scholar has ever been able to turn up. He escorted the nearly blind James Thurber to his dalliances with secretaries and deliberately put on Thurber’s socks inside out so that his wife would notice, later boasting that one secretary was “the ugliest thing you’ve ever seen.” Biographer Gerald Clarke chronicled how Capote befriended New Yorker office manager Daise Terry, who was feared and disliked by many at the magazine, because he knew she could help him. (Capote’s tactics paid off. Terry gave him the easiest job on staff: copyboy on the art department.) If Capote wanted to know you, he wanted to use you. But the beginnings of a man willing to do just about anything to get ahead can be found in his early childhood.

Truman Capote was a feverish liar and a frenzied opportunist from the first moment his high voice pierced the walls of a literary elite eager to filth up its antimacassars with gossip. He used his looks to present himself as a child prodigy, famously photographed in languorous repose by Harold Halma to incite intrigue and controversy. He claimed to win national awards for his high school writing that no scholar has ever been able to turn up. He escorted the nearly blind James Thurber to his dalliances with secretaries and deliberately put on Thurber’s socks inside out so that his wife would notice, later boasting that one secretary was “the ugliest thing you’ve ever seen.” Biographer Gerald Clarke chronicled how Capote befriended New Yorker office manager Daise Terry, who was feared and disliked by many at the magazine, because he knew she could help him. (Capote’s tactics paid off. Terry gave him the easiest job on staff: copyboy on the art department.) If Capote wanted to know you, he wanted to use you. But the beginnings of a man willing to do just about anything to get ahead can be found in his early childhood.

Capote’s cousin Jennings Faulk Carter once described young Truman coming up with the idea of charging admission for a circus. Capote had heard a story in the local paper about a two-headed chicken. Lacking the creative talent to build a chicken himself, he enlisted Carter and Harper Lee for this faux poultry con. The two accomplices never saw any of the money. Decades later, Capote would escalate this tactic on a grander scale, earning millions of dollars and great renown for hoisting a literary big top over a small Kansas town after reading a 300 word item about a family murder in The New York Times. Harper Lee would be dragged into this carnival as well.

The tale of how two frightening men murdered four members of the Clutter family for a pittance and created a climate of fear in the surrounding rural area (and later the nation) is very familiar to nearly anyone who reads, buttressed by the gritty 1967 film (featuring a pre-The Walking Dead Scott Wilson as Dick Hickock and a pre-Bonnie Lee Bakley murder Robert Blake as Perry Smith) and a deservedly acclaimed 2005 film featuring the late great Philip Seymour Hoffman as Capote. But what is not so discussed is the rather flimsy foundation on which this “masterpiece” has been built.

The tale of how two frightening men murdered four members of the Clutter family for a pittance and created a climate of fear in the surrounding rural area (and later the nation) is very familiar to nearly anyone who reads, buttressed by the gritty 1967 film (featuring a pre-The Walking Dead Scott Wilson as Dick Hickock and a pre-Bonnie Lee Bakley murder Robert Blake as Perry Smith) and a deservedly acclaimed 2005 film featuring the late great Philip Seymour Hoffman as Capote. But what is not so discussed is the rather flimsy foundation on which this “masterpiece” has been built.

Years before “based on a true story” became a risible cliche, Capote and his publicists framed In Cold Blood‘s authenticity around Capote’s purported accuracy. Yet the book itself contains many gaping holes in which we have only Smith and Hickock’s words, twisted further by Capote. What are we to make of Bill and Johnny — a boy and his grandfather who Smith and Hickock pick up for a roadside soda bottle-collecting adventure to make a few bucks? In our modern age, we would demand the competent journalist to track these two side characters down, to compare their accounts with those of Smith and Hickock. Capote claims that these two had once lived with the boy’s aunt on a farm near Shreveport, Louisiana, yet no independent party appears to have corroborated their identities. Did Capote (or Hickock and Smith) make them up? Does the episode really contribute to our understanding of the killers’ pathology? One doesn’t need to be aware of a recent DNA test that disproved Hickock and Smith’s involvement with the quadruple murder of the Walker family in Sarasota County, Florida, taking place one month after the Clutter murders, to see that Capote is more interested in holding up the funhouse mirror to impart specious complicity:

Hickock consented to take the [polygraph] test and so did Smith, who told Kansas authorities, “I remarked at the time, I said to Dick, I’ll bet whoever did this must be somebody that read about what happened out here in Kansas. A nut.” The results of the test, to the dismay of Osprey’s sheriff as well as Alvin Dewey, who does not believe in exceptional circumstances, were decisively negative.

Never mind that polygraph tests are inaccurate. It isn’t so much Hickock and Smith’s motivations that Capote was interested in. He was more concerned with stretching out a sense of amorphous terror on a wide canvas. As Hickock and Smith await to be hanged, they encounter Lowell Lee Andrews in the adjacent cell. He is a fiercely intelligent, corpulent eighteen-year-old boy who fulfilled his dormant dreams of murdering his family, but Capote’s portrait leaves little room for subtlety:

For the secret Lowell Lee, the one concealed inside the shy church going biology student, fancied himself an ice-hearted master criminal: he wanted to wear gangsterish silk shirts and drive scarlet sports cars; he wanted to be recognized as no mere bespectacled, bookish, overweight, virginal schoolboy; and while he did not dislike any member of his family, at least not consciously, murdering them seemed the swiftest, most sensible way of implementing the fantasies that possessed him.

We have modifiers (“shy,” “ice-hearted,” “gangsterish,” “silk,” “scarlet,” “bespectacled,” “bookish,” “virginal,” “swiftest,” and “sensible”) that conjure up a fantasy atop the fantasy, that suggest relativism to the two main heavies, but there is little room for subtlety or for any doubt in the reader’s mind. Capote does bring up the fact that Andrews suffered from schizophrenia, but diminishes this mental illness by calling it “simple” before dredging up the M’Naghten Rule, which was devised in 1843 (still on the books well before psychiatry existed and predicated upon a 19th century standard) to exclude any insanity defense whereby the accused recognizes right from wrong. But he has already tarnished Andrews with testimony from Dr. Joseph Satten: “He considered himself the only important, only significant person in the world. And in his own seclusive world it seemed to him just as right to kill his mother as to kill an animal or a fly.” I certainly don’t want to defend Andrews’s crime (much less the Clutter family murders), but this conveniently pat assessment does ignore more difficult and far more interesting questions that Capote lacks the coherence, the empathy, or the candor to confess his own contradictions to pursue. Many pages before, in relation to Hickock, Capote calls M’Naghten “a formula quite color-blind to any gradations between black and white.” In other words, Capote is the worst kind of journalist: a cherry-picking sensationalist who applies standards as he sees fit, heavily steering the reader’s opinion even as he feigns objectivity. The ethical reader reads In Cold Blood in the 21st century, wanting Katherine Boo to emerge from the future through a wormhole, if only to open up a can of whoopass on Capote for these egregious and often thoughtless indiscretions.

Capote’s decision to remove himself from the crisp, lurid story was commended by many during In Cold Blood‘s immediate reception as a feat of unparalleled objectivity, with the “nonfiction novel” label sticking to the book like a trendy hashtag that hipsters refuse to surrender, but I think Cynthia Ozick described the thorny predicament best in her infamous driveby on Capote (collected in Art & Ardor): “Essence without existence; to achieve the alp of truth without the risk of the footing.” If we accept any novel — whether “nonfiction” or fully imaginative — as some sinister or benign cousin to the essay, as a reasonably honest attempt to reckon with the human experience through invention, then In Cold Blood is a failure: the work of a man who sat idly in his tony Manhattan spread with cadged notebooks and totaled recall of aggressively acquired conversations even as his murderous subjects begged their “friend” to help them escape the hangman’s noose.

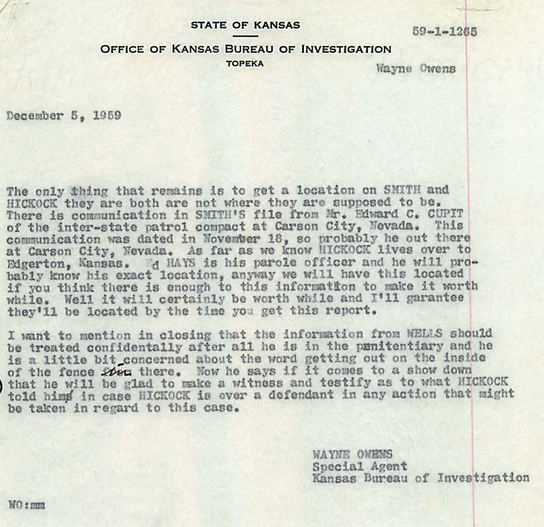

In 2013, Slate‘s Ben Yagoda described numerous factual indiscretions, revealing that editor William Shawn had penciled in “How know?” on the New Yorker galley proofs of Capote’s four part opus (In Cold Blood first appeared in magazine form). That same year, the Wall Street Journal uncovered new evidence from the Kansas Bureau of Investigation, which revealed that the KBI did not, upon receiving intelligence from informant Floyd Wells, swiftly dispatch agent Harold Nye to the farmhouse where Richard Hickock had lodged. (“It was as though some visitor were expected,” writes Capote. Expected by Hickock’s father or an author conveniently tampering his narrative like a subway commuter feverishly filling in a sudoku puzzle?) As Jack de Bellis has observed, Capote’s revisions from New Yorker articles to book form revealed Capote’s feeble command of time, directions, and even specific places. But de Bellis’s examination revealed more descriptive imprudence, such as Capote shifting a line on how Perry “couldn’t stand” another prisoner to “could have boiled him in oil” (“How know?” we can ask today), along with many efforts to coarsen the language and tweak punctuation for a sensationalist audience.

And then there is the propped up hero Alvin Dewey, presented by Capote as a tireless investigator who consumes almost nothing but coffee and who loses twenty pounds: a police procedural stereotype if ever there was one. Dewey disputes closing his eyes during the execution and the closing scene of Dewey meeting Nancy Clutter’s best friend, Susan Kidwell, in a cemetery is not only invented, but heavily mimics the belabored ending of Capote’s 1951 novel, The Grass Harp. But then “Foxy” Dewey and Capote were tighter than a pair of frisky lovers holed up for a week in a seedy motel.

Capote was not only granted unprecedented access to internal documents, but Capote’s papers reveal that Dewey provided Capote with stage directions in the police interview transcripts. (One such annotation reads “Perry turns white. Looked at the ceiling. Swallows.”) There is also the highly suspect payola of Columbia Pictures offering Dewey’s wife a job as a consultant on the 1965 film for a fairly substantial fee. Harold Nye, another investigator whose contributions have been smudged out of the history told Charles J. Shields in a December 30, 2002 interview (quoted in Mockingbird), “I really got upset when I know that Al [Dewey] gave them a full set of the reports. That was like committing the largest sin there was, because the bureau absolutely would not stand for that at all. If it would have been found out, he would have been discharged immediately from the bureau.”

In fact, Harold Nye and other KBI agents did much of the footwork that Capote attributes to Dewey. Nye was so incensed by Capote’s prevarications that he read 115 pages of In Cold Blood before hurling the book across the living room. And in the last few years, the Nye family has been fighting to reveal the details inside two tattered notebooks that contain revelations about the Clutter killings that may drastically challenge Capote’s narrative.

In fact, Harold Nye and other KBI agents did much of the footwork that Capote attributes to Dewey. Nye was so incensed by Capote’s prevarications that he read 115 pages of In Cold Blood before hurling the book across the living room. And in the last few years, the Nye family has been fighting to reveal the details inside two tattered notebooks that contain revelations about the Clutter killings that may drastically challenge Capote’s narrative.

Yet even before this, Capote’s magnum opus was up for debate. In June 1966, Esquire published an article by Phillip K. Tompkins challenging Capote’s alleged objectivity. He journeyed to Kansas and discovered that Nancy Clutter’s boyfriend was hardly the ace athlete (“And now, after helping clear the dining table of all its holiday dishes, that was what he decided to do that — put on a sweatshirt and go for a run.”) that Capote presented him as, that Nancy’s horse was sold for a higher sum to the father of the local postmaster rather than “a Mennonite farmer who said he might use her for plowing,” and that the undersheriff’s wife disputed Capote’s account:

During our telephone conversation, Mrs. Meier repeatedly told me that she never heard Perry cry; that on the day in question she was in her bedroom, not the kitchen; that she did not turn on the radio to drown out the sound of crying; that she did not hold Perry’s hand; that she did not hear Perry say, ‘I’m embraced by shame.’ And finally – that she had never told such things to Capote. Ms. Meier told me repeatedly and firmly, in her gentle way, that these things were not true.

(For more on Capote’s libertine liberties, see Chapter 4 of Ralph F. Voss’s Truman Capote and the Legacy of In Cold Blood.)

Confronted by these many disgraceful distortions, we are left to ignore the “journalist” and assess the execution. On a strictly showboating criteria, In Cold Blood succeeds and captures our imagination, even if one feels compelled to take a cold shower knowing that Capote’s factual indiscretions were committed with a blatant disregard for the truth, not unlike two psychopaths murdering a family because they believed the Clutters possessed a safe bountiful with riches. One admires the way that Capote describes newsmen “[slapping] frozen ears with ungloved, freezing hands,” even as one winces at the way Capote plays into patriarchal shorthand when Nye “visits” Barbara Johnson (Perry Smith’s only surviving sister: the other two committed suicide), describing her father as a “real man” who had once “survived a winter alone in the Alaskan wilderness.” The strained metaphor of two gray tomcats — “thin, dirty strays with strange and clever habits” – wandering around Garden City during the Smith-Hickcock trial allows Capote to pad out his narrative after he has exhausted his supply of “flat,” “dull,” “dusty,” “austere,” and “stark” to describe Kansas in the manner of some sheltered socialite referencing the “flyover states.” Yet for all these cliches, In Cold Blood contains an inexplicably hypnotic allure, a hold upon our attention even as the book remains aggressively committed to the facile conclusion that the world is populated by people capable of murdering a family over an amount somewhere “between forty and fifty dollars.” As Jimmy Breslin put it (quoted in M. Thomas Inge’s Conversations with Truman Capote), “This Capote steps in with flat, objective, terrible realism. And suddenly there is nothing else you want to read.”

That the book endures — and is even being adapted into a forthcoming “miniseries event’ by playwright Kevin Hood — speaks to an incurable gossipy strain in Western culture, one reinforced by the recent success of the podcast Serial and the television series The Jinx. It isn’t so much the facts that concern our preoccupation with true crime, but the sense that we are vicariously aligned with the fallible journalist pursuing the story, who we can entrust to dig up scandalous dirt as we crack open our peanuts waiting for the next act. If the investigator is honest about her inadequacies, as Serial‘s Sarah Koenig most certainly was, the results can provide breathtaking insight into the manner in which we incriminate other people with our emotional assumptions and our fallible memories and superficially examined evidence. But if the “journalist” removes himself from culpability, presenting himself as some demigod beyond question or reproach (Capote’s varying percentages of total recall memory certainly feel like some newly wrangled whiz kid bragging about his chops before the knowledge bowl), then the author is not so much a sensitive artist seeking new ways inside the darkest realm of humanity, but a crude huckster occupying an outsize stage, waiting to grab his lucrative check and attentive accolades while the real victims of devastation weep over concerns that are far more human and far more deserving of our attention. We can remove the elephants from the lineup, but the circus train still rolls on.