(This is the thirteenth entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: Loving)

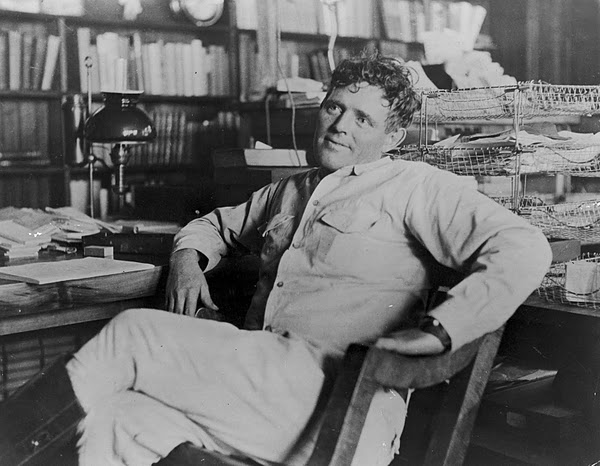

In June 1902, Cosmopolitan published “Diable — A Dog” (the original title “Bâtard” had been softened by squeamish editors) by an emerging young writer named Jack London. This gripping tale involves a dog (“illegitimate” like London: his father a timberwolf, his mother a husky) battling his vicious master Leclère as the two wander the Yukon — seemingly with the sole purpose of rending each other at any opportunity. London describes how “hate bound them together as love could never bind,” not unlike Edward Albee’s George and Martha or Eminem and Kimberly Scott. And like the most extreme bonds of blinding enmity, for Diable and Leclère, this leads to a fatal end.

In June 1902, Cosmopolitan published “Diable — A Dog” (the original title “Bâtard” had been softened by squeamish editors) by an emerging young writer named Jack London. This gripping tale involves a dog (“illegitimate” like London: his father a timberwolf, his mother a husky) battling his vicious master Leclère as the two wander the Yukon — seemingly with the sole purpose of rending each other at any opportunity. London describes how “hate bound them together as love could never bind,” not unlike Edward Albee’s George and Martha or Eminem and Kimberly Scott. And like the most extreme bonds of blinding enmity, for Diable and Leclère, this leads to a fatal end.

In December of that year and in a lonely place, London began work on a 4,000 word short story — a companion piece to “Bâtard” involving a civilized dog named Buck, who is also a mongrel, and his adventures in the Alaskan wilderness. Two months later, London had a novel. But he he would make a catastrophic business decision: $2,000 in cash from Macmillan for all rights with a further $750 to the Saturday Evening Post. Given the millions of copies that Call would go on to sell, and given London’s constant financial woes, this transaction may very well be American literature’s answer to the Dutch snapping up Manhattan from the Lenape for a mere 60 guilders.

Despite this bad business, Call would cement London’s literary reputation. And I am pleased to report that, a little less than three decades after I first read it, Call holds up remarkably well on a second and third read — so much so that I was compelled to read White Fang, a London biography, numerous critical responses, and countless other texts directly and indirectly related to Call before a kind friend cut me off from this London monomania in the manner of a respectful bartender telling an exuberant customer to go home and sleep it off. Additional friends encouraged me to read sections of White Fang aloud to an especially finicky cat and were surprised when I found that I could not stop. I could go on reading London for days. The man is that good.

My obsession likely emerged from the startling rediscovery that London’s prose remains alive in a way one would not expect from a novel published in 1903, especially since London found his inspiration to write from a somewhat incongruous source: Ouida‘s Signa. Soon after Buck is kidnapped from the “big house in the sun-kissed Santa Clara Valley,” where he lives with Judge Miller and his family, London masterfully establishes the way that the setting is changing by throwing the reader off with subtle syntactic shifts:

Several times during the night he sprang to his feet when the shed door rattled open, expecting to see the Judge, or the boys at least. But each time the joyful bark that trembled in Buck’s throat was twisted into a savage growl.

We believe that Buck springing to his feet will spawn an escape or that the door rattling open will precipitate some further action, but London establishes an uncertain feeling between understated fear and expectation. And he neatly foreshadows Buck’s inevitable transformation with the “joyful bark” twisting “into a savage growl.” This style might be identified as highly refined Alger, but it also allows us to become invested in Buck’s inner life in a manner that feels tough rather than sappy, transcendental rather than fixed. And we become so involved with Buck’s struggles that we forget we are reading an animal tale.

But Call has more going on than a soft Southland mutt growing into a legendary Ghost Dog who “sings a song of the younger world.” London, who spent much of his formative years laboring hard as a “work beast,” is also writing about the honor and integrity that emerge from doing a job well even in the worst of all possible worlds. This wild world of hard labor, in which one must eat faster and push one’s muzzle harder to grab that bit of protein needed to keep pulling the sleds and one must ward off belligerent “co-workers” like Spitz (if you think you’ve got annoying cubemates, wait until you meet this dog), still has its virtues:

Best of all, perhaps, he loved to lie near the fire, hind legs crouched under him, fore legs stretched out in front, head raised, and eyes blinking drearily at the flames. Sometimes he thought of Judge Miller’s big house in the sun-kissed Santa Clara Valley, and of the cement swimming tank, and Ysabel, the Mexican hairless, and Toots, the Japanese pug; but oftener he remembered the man in the red sweater, the death of Curly, the great fight with Spitz and the good things he had eaten or would like to eat. He was not homesick. The Sunland was very dim and distant, and such memories had no power over him. Far more potent were the memories of his heredity that gave things he had never seen before a seeming familiarity; the instincts (which were but the memories of his ancestors become habits) which had lapsed in later days, and still later, in him, quickened and became alive again.

Work, which comes by necessity in the wild, overcomes the distressing prospect of being crippled by memory. It unites disparate souls, even those who are lashing at each other, and even causes experienced men to protest the clueless chekakos. Midway through the novel, three greenhorns show up with canned goods, “blankets for a hotel,” and beat their dogs into submission without lightening the load. Later in the novel, Buck makes his escape from this unthinking and irresponsible trio into John Thornton’s care.

While it’s true that unfastening a lock can require pluck, some critics have made too much hey now over certain autobiographical connections between Jack and Buck. It is true that London was writing The Call of the Wild as his first marriage was disintegrating. Buck does describes his love for John Thornton with lilting romance (“But love that was feverish and burning, that was adoration, that was madness, it had taken John Thornton to arouse”*), but London wrote these words before he had Charmian Kittredge, the woman who could match London’s libido and physical activity (she even boxed with him) and who would become his second wife. (And since I’m dishing out gossip, I should probably point out that London, licentious even as his belly bulged from drink, still cheated on her.)

If work can save you, it doesn’t necessarily eliminate class struggle, which London would explore more fully in his needlessly overlooked novel, Martin Eden. London’s daughter, Joan, would write that Call was “the story of all strong people who use the cunning of their minds and the strength of their bodies to adapt themselves to a difficult environment and win through to live,” but this strikes me as a little pat. It is certainly interesting that The Call of the Wild and The Sea-Wolf both rely on bourgeois protagonists being plucked from their safe environments in order to learn invaluable lessons in individualism and morality. Perhaps you can learn such lessons within middle-class comforts. But London’s romantic view makes a compelling case that it is better for instincts to quicken and become alive when you are thrown outside your comfort zone. In other words, every MFA student and passive-aggressive vacillator needs to read Jack London pronto.

* — This seems as good a time as any to bring up the relationship between The Call of the Wild and London’s companion novel, White Fang, which depicts the transformation in reverse (wild wolf turning into civilized dog, complete with another judge taking care of White Fang near the end, suggesting a symmetry with London’s earlier volume). While I enjoyed White Fang quite a lot, I consider it to be the inferior volume, rehashing many story elements of Call (wolves getting into a squabble over a rabbit, rising to sled leader, and so forth) and not quite possessing the poetry and the tautness and the keen insight and the gripping gusto that’s there in Call. The passage I quote here about Buck’s love for John Thornton doesn’t feel nearly as schmaltzy as its heavy-handed counterpart in White Fang: “Human kindness was like a sun shining upon him, and he flourished like a flower planted in good soil.”

Next Up: Arnold Bennett’s The Old Wives’ Tale!