Jennifer Weiner appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #346. She is most recently the author of Fly Away Home. Ms. Weiner previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #198 and The Bat Segundo Show #14.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Hoping to be frightened by The Motherland sometime soon.

Author: Jennifer Weiner

Subjects Discussed: [List forthcoming]

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: It seems to me that you are really gravitating more towards this extremely dark expanse of human behavior. At least from my vantage point. And it seems that you really want to push further in this direction. And yet, to some degree, you almost stop short of really pushing yourself fully into something so dark. And I know you’ve got it in you. So I’m wondering: why ride the comic tone? Out of obligation to your readers? Or what here?

Weiner: Well, I think, for me, it always feels natural to have both. To have the darkness and the comedy. That’s just how I am as a person. And I think that my own family history has made me that way. There’s been horrible things that have happened, but me and my sister and my brothers always wind up laughing about it. Because what else can you do? But it’s interesting. That darkness. Because it’s a tough tension to maintain. And I don’t want… (pause) See, here’s the thing. I don’t think writers choose the books they’re trying to write. I don’t think writers choose the tone they’re going to take. I think that it’s a blood type. Like it’s what you’re born with. Stephen King gave the example. He and Louis L’Amour could be sitting at a pond. And Louis L’Amour would come up with this Western about water rights in a town that was having a drought, and what would happen? And Stephen King would write about something that comes slithering onto the banks, and first takes the dogs, and then takes the cattle, and then takes the kids. It’s just the way you’re wired. And I think that I’m wired, for good or for ill. I mean, there was a lot of sad stuff in Good in Bed too.

Correspondent: That’s true. But we’re talking about rape.

Weiner: Rape.

Correspondent: We’re talking about neglected children.

Weiner: Yes.

Correspondent: And during those sections in both of these last two books, it gets really, really serious.

Weiner: Right.

Correspondent: And then we go back to the laughs. But I’m wondering why not go ahead and spread this further? It’s not to say that you can’t explore light and dark. You can do a double plot thing. Like Crimes and Misdemeanors or something. I don’t know.

Weiner: (laughs) And then when you turn the book over…

Correspondent: (laughs) Yes.

Weiner: …they go shoe shopping!

Correspondent: Yeah, exactly.

Weiner: Well, who’s doing that well? Zoe Heller obviously.

Correspondent: Yes.

Weiner: Who else? Who do you like? Because Zoe Heller’s funny too.

Correspondent: I’ll bring up Richard Russo. Richard Russo does that very well too. And in fact, I….

Weiner: Mmmmm. My mother loves him.

Correspondent: I’m trying to go ahead — you and Russo are actually on the same team here. You know, that whole description of the development of the grocery store?

Weiner: Yes. Yes.

Correspondent: I could find that in a Richard Russo book, as I could in a Jennifer Weiner book. He writes about this kind of stuff too.

Weiner: Right.

Correspondent: You write about this too. And I’m telling you. What do we do to get some kind of diplomacy here?

Weiner: But I…

Correspondent: It’s not Russo’s fault that your mother was blabbing about him!

Weiner: Oh my god.

Correspondent: It wasn’t his fault.

Weiner: Okay, let me set the scene for you. The year is 2001.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Weiner: And my first book is out. And I’m in a bookstore with my mother. And I’m signing stock, as you do. And my mother, who is very friendly and chatty. This woman comes up to her and says, “Oh, I need a great book for the summer. Have you read anything?” And my mother says, “I just read the best book. It was funny and it was sad. And the characters felt so real.” And I’m like, “Wait for it. Wait for it.” And my mom’s like, “It’s called Empire Falls by Richard Russo.” And I’m like, “Mom!” Because do you think that Richard Russo’s mom is up in Maine pimping my books?

Correspondent: But your mother was probably pimping your book too!

Weiner: Uh uh.

Correspondent: No?

Weiner: Mmm mmm.

Correspondent: Not at all?

Weiner: Well, maybe a little bit.

Correspondent: Oh okay. Well, there you go.

Weiner: But I think the woman asked what she read that she loved. And I think that [my mother] read Good in Bed in galley months ago. But, no, I love Richard Russo. But I don’t know.

Correspondent: So wait. You have read him.

Weiner: Of course!

Correspondent: Okay. Okay. So this is…

Weiner: I’m not a philistine here!

Correspondent: (laughs) So what’s the issue here? It can’t just be your mom. There’s something else going on here.

Weiner: I like Richard Russo. Have I talked smack about him?

Correspondent: Yeah. You’ve been suggesting, “Oh. Richard Russo. I don’t talk about him because of this whole mother thing.”

Weiner: It’s a joke! It’s a joke!

Correspondent: Okay.

Weiner: I like him. I don’t like Jonathan Franzen.

Correspondent: Yeah.

Weiner: But I don’t think Jonathan Franzen likes anybody. So I think it’s all good. Like I don’t think he wants me — I don’t know? Does he want to be liked? Did you read the essay that his girlfriend wrote?

Correspondent: Yes.

Weiner: Where was it? The Paris Review?

Correspondent: Kathy Chetkovich. It was in Granta. [EDITORIAL NOTE: Issue 82, to be precise. Now behind a paywall, but an excerpt appeared in The Observer. See above link.]

Weiner: Granta.

Correspondent: Yes. Exactly.

Weiner: Weird guy. About birding.

Correspondent: Yeah, I know. But actually, since we’re talking about the literary world…

Weiner: Yes!

Correspondent: I should also bring this up. Why give so much credit to The New York Times Book Review? I mean, this whole thing with the full-page advertisement.

Weiner: I know.

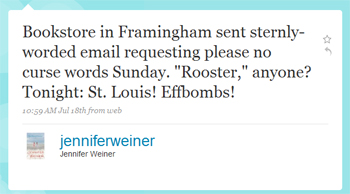

Correspondent: And I read your Twitter feed. And I know that you’re there on a Friday afternoon. At 5:00. When they put up the new articles. And you are looking through those articles.

Weiner: Right.

Correspondent: Why? Why give these folks credence?

Weiner: Well, you know what it is? They’re kind of the only game left in town. The Philadelphia Inquirer, where I used to work, once had a free-standing books section. And there used to be — I think the Hartford Courant, where I grew up, had a books section once upon a time. But honest to god, the truth is that my dad read The New Yorker and read The New York Times Book Review, and would get all of his reading suggestions from those two places. So if you weren’t in there, you didn’t really matter. And I think that I internalized that to a very great extent. But honestly, I think that the die was cast when I went with Atria instead of Simon & Schuster. Like way back in the day. When I was choosing who was going to publish my first book. And it’s like, well, Atria is much more commercial. And I knew that I loved my editor. I love my editor still. I love my publisher. They got the book. Like on a really visceral level. They were going to a great job of promoting it. Do a great job with me. But I wasn’t going to get reviewed by the Times. But then again, if you call your book Good in Bed, are you ever going to get reviewed by the Times? I don’t think so.

Correspondent: Unless you name it The Surrender.

The Bat Segundo Show #346: Jennifer Weiner III (Download MP3)

(Image: pplflickr)