Jennifer Weiner appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #469. She is most recently the author of The Next Best Thing.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Ms. Weiner previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #14, The Bat Segundo Show #198, and The Bat Segundo Show #346.

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Wondering if Joe Esposito might be right about his questionable stature.

Author: Jennifer Weiner

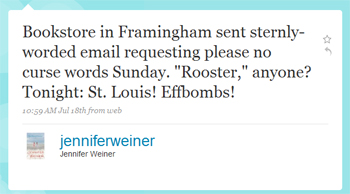

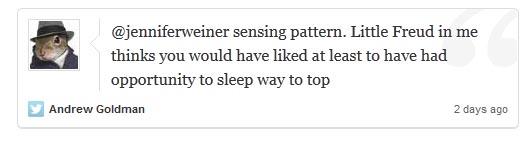

Subjects Discussed: The summer heat, the size and details of Weiner’s entourage, bagels, physically scarred protagonists, broken people who work in the entertainment industry, the relationship between physicality and the emotional underpinning of a character, the writers’ room as group therapy session, using autobiographical details for fiction, exaggerating raw material, making the readers believe, the writer as precious snowflake, fighting TV network brass over the word “ass-munch,” Barbra Streisand’s litigious nature, the Eugenides Vest campaign and one percenter jokes, Louis CK, scheduling difficulties with Raven-Symoné, whether The Next Best Thing is roman à clef, television audiences vs. reading audiences, reaching young women, Girls, the YA market, Pippi Longstocking, talented TV writers who can’t manage people, Dan Harmon, pretending that adults are teenagers, why Weiner wants more, the inevitability of any arStist having haters, the Alice Gregory shiksa lit article, daddy complexes, Sylvia Plath, straying from characters who are besieged by financial problems, State of Georgia, pursuing fantasy-based elements when America faces high unemployment, tackling social issues in Then Came You, writers with obnoxious public personae, the income disparity between Weiner and her audience, social media and privacy, eclectic reading, getting behavior right, the income gender gap, unemployed men and gainfully employed women in a relationship, USA Today‘s review, Julia Phillips’s You’ll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again, William Goldman’s “Nobody knows anything,” Garry Shandling, The Larry Sanders Show, gender lines in comedy, Ginna Bellafante’s gender reductionism in relation to A Game of Thrones, Curb Your Enthusiasm, cringe comedy, Peep Show, David Mitchell not reading his reviews, Janet Maslin’s factual inaccuracies in her reviews, redacted book reviews, when women are asked to please, ambition as a negative female quality, fears of losing an audience, Emily Giffin, Jane Green, the risk of taking breaks between books, Laura Lippmann, Lisa Scottoline, slowing the six to nine month book cycle down, Susan Isaacs’s generational epics, being known as a loudmouth vs. being known as ambitious, Macbeth, the book-a-year productivity, Philip Roth, the problems with Ian McEwan’s On Chesil Beach, being too eager to please, why it’s important to write a second book immediately after writing a first book, replying to readers on Twitter, Goodreads, trying not to look at reviews, writing a character who demands assurance, Nikki Finke, women taking responsibility for their own orgasms, Caitlin Flanagan’s oral sex sensationalism, sex as an obligation for women, whether or not The New York Times Book Review really matters, Cheryl Strayed outing herself as Dear Sugar, women winning the National Book Awards, Jennifer Egan, cultural arbiters rooted in nostalgia, fragmented books culture, the collapse of Borders, Dwight Allen’s snotty Stephen King article, living in a post-critical culture, attention, the gender imbalance in The New York Times Book Review, the considerable virtues of Pamela Paul, addressing criticisms from Roxane Gay, reduced stigmas against women’s fiction and genre in the last fifteen years, and the need for loudmouth women.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I have to ask. Did you actually fight network brass over the word “ass-munch”?

Weiner: Yes.

Correspondent: You did?

Weiner: Yes, I did.

Correspondent: Really? And there was this kind of exchange of viewpoints?

Weiner: M’hmmm.

Correspondent: And “ass-munch” was just unacceptable.

Weiner: Yeah, exactly.

Correspondent: Even though I hear twelve years olds say it all the time.

Weiner: Yeah. It’s like they said “blow job” on NYPD Blue and I can’t have an “ass-munch”? And they’re like, “We’re ABC Family.” And I’m like, “You’re a different kind of family. It says so right on your logo.”

Correspondent: Yes.

Weiner: I want my “ass-munch.”

Correspondent: Yes.

Weiner: And I was denied my “ass-munch.”

Correspondent: What other words did they deny you during this time?

Weiner: You know, it wasn’t words so much as people.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Weiner: Seriously. The part about not being able to make jokes about Barbra Streisand? I guess she’s both very sensitive and very litigious.

Correspondent: So that actually happened too.

Weiner: That happened too.

Correspondent: Wow. Were there any other public figures who were declared verboten?

Weiner: No.

Correspondent: Just Barbra? (laughs)

Weiner: Just Barbra. But, you know, the funny thing was we had this line about Bruce Jenner. And Honey, who is sort of the Auntie Mame character, is like, “Now you girls probably just know him as the crazy old lady in the Kardashian house.” And I was like, “Oh my god. Standards and Practices is never going to let this go.” I guess Bruce Jenner got the joke. In fact, we approached him to play the part. To come down the stairs, as if he’d been in bed with Aunt Honey.

Correspondent: Going from these battles with Standards and Practices back to fiction writing, I have to ask — I mean, especially in light of the one percenter joke idea, which, oddly enough, your recent Eugenides Vest campaign…

Weiner: I hope we talk about that.

Weiner: I hope we talk about that.

Correspondent: Well, we can. I’d be happy to. But it is interesting to me that you come from television, your foot is laid down for things like “ass-munch,” for esoteric references or seemingly esoteric references.

Weiner: Yes, the one percenters.

Correspondent: How do you unlearn some of these necessary exigencies when you’re writing? When you’re coming back to fiction? I have to ask you about this. Because when you’re in such an intense show biz environment, having to produce and having to fight and having to compromise and having to go ahead and create art in a highly commercial medium, how do you go to a slightly less commercial medium, like books, and be true to that voice that established you in the first place?

Weiner: For whatever reason, I didn’t have a hard time with it. I don’t know if that’s just a way that I’m lucky. But I didn’t have a hard time going from, like you said, the very mediated world of commercial TV to the world of novel where it’s just you and the people in your head and “We’ll see you in a year with that manuscript.” It wound up being okay. But, God, I loved being in a writers’ room. I miss it every day.

Correspondent: You want to go back to a writers’ room?

Weiner: I would like to go back to a writers’ room someday. It would be different, I think.

Correspondent: Even with the battles?

Weiner: Even with the battles. Because I think that there’s cases where it goes so right and the stars kind of align. And then I also think there’s different ways of doing entertainment. Like Louis CK. Where it’s basically like “Okay, network, you give me X number of dollars. I will give you Y number of shows. And no notes.”

Correspondent: But that’s a very uncommon situation. It doesn’t happen to everyone. Even you probably couldn’t get what he has.

Weiner: Well, but then there’s people doing stuff on the Web. Where it’s like, I don’t want a network. I don’t want notes. I don’t need your money. I’m going to Kickstart this thing or raise money myself and it will just be my vision unmitigated. That’s what I think we’re going to start seeing more of. Because I think that there’s going to be increasing frustration with “You can’t say that!” Or “You can’t say that about that person.” “You can’t use those words.” “We want you to do it with this actress.” And that, to me, was the hardest part. I went out there. I wanted to do a show about a big girl. And the network, ABC Family, had a holding deal with Raven-Symoné. Who during that, Raven had been a bigger girl.

Correspondent: Yes. Also put into the novel.

Weiner: Yes! And I’m like, “Fantastic! That’s great!” I mean, I guess she won’t be Jewish But we’ll deal with that. And then I want to sit down and meet with her and talk about the part and talk about how she relates to the character and where the character comes from. And they’re like “She’s busy. She’s busy. She’s traveling. She’s on vacation.”

Correspondent: So she really would not meet with you.

Weiner: Would not meet with us.

Correspondent: Wow.

Weiner: And I remember thinking they kept saying, “She’s on vacation.” And I’m like, “On vacation from what?”

Correspondent: Why didn’t you just track her down yourself?

Weiner: She was in Hawaii.

Correspondent: She was in Hawaii. Why not fly on a plane?

Weiner: I should have!

Correspondent: And say “Raven, what’s up?”

Weiner: In retrospect, in retrospect.

Correspondent: So this is very roman à clef, it sounds like!

Weiner: It is a little.

Correspondent: But did she follow you on Twitter? (laughs)

Weiner: I don’t think she did.

Correspondent: She did not!

Weiner: I don’t think she followed me on Twitter.

Correspondent: Wow.

Weiner: I gave her a bunch of my books. I’m not sure she read them.

Correspondent: Did she overact? As you suggest? This particular…

Weiner: I think no.

Correspondent: I know you have to be careful here.

Weiner: No. I actually think she’s got great comic chops. I think that she grew up in front of a camera. I mean, this is a girl who shot her first commercial at age nine months. She’s been a working actress for her whole life, basically. Which produces its own kind of dynamic. Which is a very interesting dynamic where you’ve got a child supporting parents. And that’s a whole other book.

Correspondent: But going back to this issue of, well, you couldn’t meet with her. I mean, this has got to be extremely frustrating for you.

Weiner: Yes! Right.

Correspondent: Speaking as someone who is largely on the literary field, and sometimes goes into independent film and so forth, you know, this has got to be, from my vantage point at least, an extremely creatively frustrating experience. What does television offer that fiction does not?

Weiner: Well, you know what it offers? I’ll tell you…is an audience. Because the absolute…

Correspondent: You’ve got an audience though!

Weiner: But listen.

Correspondent: Alright.

Weiner: The absolute bestselling novel in its first week will sell, say, half a million copies. Okay, that is how many people will tune into the lowest rated rerun of a Kardashian show.

Correspondent: Which is frightening.

Weiner: Which is frightening and sad. But if you want to talk to young women, you go beyond TV.

Correspondent: If you want to talk with young women.

Weiner: If you want to talk to young women.

Correspondent: Why do you need that large audience?

Weiner: I want to talk to young women. I mean, I remember watching TV as a young woman and there was never anybody who looked like me. Unless she was the butt of a joke or the funny best friend or somebody tragic. Somebody who needed a makeover in order for good things to happen. And I have daughters. And they’re both blonde-haired, blue-eyed. They’re very cute little girls. I’ve basically given birth to my own unit of the Hitler Youth. I don’t get it. But I want to make shows for girls where the heroine doesn’t look like Blake Lively. Where the heroine looks like a regular girl and still gets everything. Gets the guy, gets the jokes, gets the great clothes, gets the great job. That’s what I went out there to do.

Correspondent: Well, Jen, I’m all for creative idealism as much as the next person. I mean, this program prides itself on its creative control. However, you got Raven.

Weiner: I went to the wrong place maybe.

Correspondent: Yes, exactly.

Weiner: I got Raven minus thirty pounds.

Correspondent: You really can’t always get what you want when it comes to television. So it seems to me that wouldn’t you be better off? You know, you can do pretty much whatever you want, I’m thinking…

Weiner: In a book.

Correspondent: Within a book. That you can’t do through television.

Weiner: Well, you know, I hope though — and I think I’m going to keep banging at that door. Because I do think — you look at a show like Girls on HBO.

Correspondent: Which I’m a big fan of, oddly enough. I never expected to say that.

Weiner: Yeah. But I think that there are people on networks who would say, “Well, no, we don’t want people that look like that on TV. We have to sell Valley Fitness commercials.” Well, HBO does not have to sell Valley Fitness commercials.

Correspondent: No.

Weiner: They just have to have subscribers.

Correspondent: They also don’t need that great of an audience.

Weiner: Exactly.

Correspondent: Which is why they have the shows that they do.

Weiner: Right. They can have a hit if half a million people watch. Where a network, you’d be cancelled before you got to the first commercial. So there’s places it can happen. There’s ways that it can happen. And I would like to keep trying.

Correspondent: But you have very skillfully evaded my main question.

Weiner: Yes.

Correspondent: Which is: You have an audience.

Weiner: I do.

Correspondent: You have a great audience.

Weiner: They love me.

Correspondent: You have an audience of girls and young women and women. And I’m saying to myself, “Well, that’s fantastic. Why isn’t that enough?”

Weiner: Well, that’s an interesting question.

Correspondent: (laughs) Nice media training there, Jen. (laughs)

Weiner: Well, you know what? I think that I’m someone who’s wired to want more. I don’t know why. I don’t know why. Maybe it’s daddy stuff. I don’t know. But I see gaps and problems and imbalance and inequity. And for whatever reason feel compelled to talk about it. You know, whether it’s the New York Times not covering women.

Correspondent: We’ll get to that.

Weiner: We’ll get to that. Whether it’s television offering a range of beauty that goes from a size zero all the way up to a size two. And it’s like, well, maybe I can do something about that. And I feel like I need to try.

Correspondent: Yeah. But it seems to me that you’re reflecting some sort of personal imbalance and stretching it into some sort of societal imbalance, creating yet another form of imbalance. I mean, why isn’t the work itself enough? Because you can always stretch yourself on that canvas. You can always try new things on the page.

Weiner: But again, who’s reading?

Correspondent: I’m reading. You have millions of people reading you.

Weiner: I don’t know if fourteen-year-old girls are — I think they’re reading Twilight. And that concerns me some.

Correspondent: They’re also reading. I mean, China Miéville, he’s writing YA books and he writes his literary books.

Weiner: This is true.

Correspondent: You can do something like that.

Weiner: I’m actually working on a YA book.

Correspondent: You are?

Weiner: Yes. Thank you for asking. I’m writing — you remember Pippi Longstocking?

Correspondent: Yes.

Weiner: Okay, so, ten-year-old girl who is living alone with a monkey named Mr. Jingles.

Correspondent: Absolutely.

Weiner: And I remember reading that and loving it. Because she has these adventures and she’s kind of an ass-kicker. Like she’s got huge feet and she sort of takes on the mean boys. And I’m like, I read it as a girl and loved it. I read it as a mom to my daughter. And I’m like, this is the most fucked up thing I’ve ever seen in my life. Why is this child living by herself with a monkey? Like what the…you know. So what I’m writing is a story about a girl who comes home from school one day and discovers her parents are missing. They’re just gone. And she doesn’t tell anybody. Because she knows that the instant that people realize her parents aren’t there, she’s going to be shipped off to her horrible aunt in Texas. And she sort of scams her way through a school year and figures out all of these tricks. My favorite one is that she signs up for a diet service to deliver her all her food. She doesn’t know how to cook. So she’s an ad on late night TV. Like “We’ll bring you three meals and two snacks every day.” So she calls up and she’s like, “It’s for my mom. I want to surprise her.” And the lady’s like, “Oh honey, that’s so sweet. How big is your mom?” So she makes up the biggest number she can think of. So she’ll get a lot of food. So I am interested in thinking about YA and thinking about reaching an audience that way. But I think television just offers — it’s a great canvas to tell a story. It gives you space. It gives you time. It gives you visibility.

Correspondent: You’ve got visibility. You’ve got time.

Weiner: Yeah, I know.

The Bat Segundo Show #469: Jennifer Weiner IV (Download MP3)

This text will be replaced

Weiner: I hope we talk about that.

Weiner: I hope we talk about that.