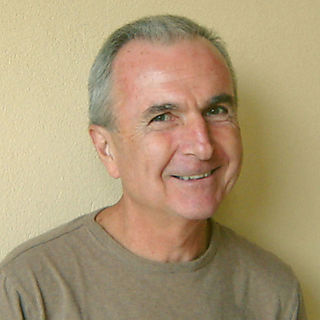

Eric Kraft appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #269.

Eric Kraft is most recently the author of Flying. This is the second of a three part conversation with Kraft about all of his Peter Leroy books, an epic of more than a million words which Our Young Roving Correspondent was insane enough to read. These podcasts tie in with a roundtable discussion of Flying involving numerous people.

(To listen to Part One of this conversation, go here. To listen to Part Three of this conversation, go here.)

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Astonished by the celerity of interlocutor and author.

Author: Eric Kraft

Subjects Discussed: The notion of roles in the Peter Leroy books, King Lear, Peter Leroy’s alternative universe, the Muddleheaded Dreamers Motorcycles Club, Marlon Brando, the halfway house between the real world and the imaginary world, geek swagger, adjusting to contemporary folkways when writing about the 1950s, whether truth is findable within limitations, the old definitions of novel, Herman Melville, Pandora in the Congo, Perry Melville’s The Raven and the Whale, increased emphasis on formalist structure in the Leroy books, borrowing structures from other books, Raskol vs. Raskolnikov, being informed by other literary work, Don Quixote, on not knowing narrative details in advance, the risk of losing spontaneity, writing in the predawn hours, martinis at 5:00 PM, the North American Proust Society, the concern for construction in the Leroy books, Peter and Albertine shifting from hotel proprietors to hotel occupants, having twenty titles for future books, the Peter Leroy books on CD-ROM, uphill battles with publishers, why the Leroy books went out-of-print, cross-references and hyperlinks, the epidemic of vidiocy, Kraft’s changing views on online annotation, and the future of the book.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Kraft: Peter’s alternative universe at the time of Flying is located at something like 1960 in our universe and in our America. And at that time, the definition of the roles available to a boy his age were quite rigid. And the number of options was quite narrow. Things were not as fluid, certainly as they are now. And that’s one of the things. When I put myself back in the time from my life that was going to have to serve as the basis for Peter’s, it was something that I reacted against and found laughably limiting. At the time, it was frustrating and annoying. But now, from distance, in how much has happened and how many more options are open to a boy like Peter, it seemed laughable. And so it became essentially laughable. But you know, a lot of those roles were defined not directly, but by various cultural artifacts. You mentioned the MDMC — the Muddle-Headed Motorcyclists Club — and Johnny is the leader of that. Well, Johnny — the portrait of Johnny when you first see him — is exactly Marlon Brando in The Wild Bunch. I mean, there he is. With the same sort of cab driver’s cap and so on. So I very deliberately littered the ground with these references to the kind of cultural role-defining models that existed at that time.

Kraft: Peter’s alternative universe at the time of Flying is located at something like 1960 in our universe and in our America. And at that time, the definition of the roles available to a boy his age were quite rigid. And the number of options was quite narrow. Things were not as fluid, certainly as they are now. And that’s one of the things. When I put myself back in the time from my life that was going to have to serve as the basis for Peter’s, it was something that I reacted against and found laughably limiting. At the time, it was frustrating and annoying. But now, from distance, in how much has happened and how many more options are open to a boy like Peter, it seemed laughable. And so it became essentially laughable. But you know, a lot of those roles were defined not directly, but by various cultural artifacts. You mentioned the MDMC — the Muddle-Headed Motorcyclists Club — and Johnny is the leader of that. Well, Johnny — the portrait of Johnny when you first see him — is exactly Marlon Brando in The Wild Bunch. I mean, there he is. With the same sort of cab driver’s cap and so on. So I very deliberately littered the ground with these references to the kind of cultural role-defining models that existed at that time.

Correspondent: But the MDMC is something of a halfway house between the real world and the imaginary world. It’s almost as if a swagger, which is a big component of this particular book, is something that is presented as an almost alternative form of swagger. I would call it “geek swagger,” which has come an increasingly acceptable notion in contemporary culture. But it also brings to mind what you just described in your answer. And that is you’re writing from your own memories filtered through Peter Leroy, and you’re writing from a time in which folkways are different, mores are different. The way in which we accept things are different. So is the artificial universe the way to find this halfway house? Similar to the MDMC? In order to create a “true” narrative? What’s the situation here?

Kraft: Well, this is the question I’m constantly asking myself. I know that there is an essential truth running through these books somewhere. If I could only find it. (laughs) There’s a time where I thought I was directly heading for it. That I knew it would be something that lay between Peter’s world and my world. And that I probably had a much better chance of success at displaying it if I focused on Peter’s world. Because mine would be an attempt at an honest memoir. And it’s impossible to write an honest memoir. It’s impossible to write a true memoir. As you said, every perception is a misperception to begin with. And from there, it just becomes more and more of a distortion. Can’t be done. However, if you work on the reflection instead, you may be able to adequately suggest the truth of the underlying facts. But finding them is the work of the reader. So because I’m so involved with this, I can no longer quite tell whether that truth is findable, is discoverable. I hope it is. And one aspect of it is, for example, this limiting effect of the roles that society was forcing on people back then. You saw it. So it was there.

Correspondent: Sure. But simultaneously, I might also counterargue that, because the form of this book is different from most novels, that truth, that verisimilitude, really shouldn’t matter so much. So, in a sense, you are both looking for the truth while also redefining what the truth is. And I’m wondering. This must create a dilemma for you when you’re writing any of these particular books. How do you go in and set yourself straight? This is the real I know, and this is the imaginary. We can go Lacan on this.

Kraft: This is a delicious dilemma. This is part of the pleasure of making the books. And I hope it’s part of the pleasure that the reader takes from them. The way I play with verisimilitude is, I hope, a way of scattering treats for the reader. I think it’s what I call absurd verisimilitude. Let’s drop back a bit. Here we are in Edgar’s Cafe. Well, at the time of Poe and Melville, the word “novel” was not what we use it for now. A novel was a true account. A novel would be what we call a memoir today. When Melville wrote Typee, he announced, “This was a novel. It’s all true! It all happened to me!” The opposing form — what we would have in opposition to memoir now is a novel. What was in opposition to a novel was a romance. And what made a romance succeed was not so much the flights of fancy in it, but what at the time people called resemblance. Verisimilitude essentially. Achieved primarily through accumulation of minute detail. Well, that’s what I do. There’s accumulation of minute detail. But my details, I hope, are details that lead the reader to say, “But this is preposterous!” Sometimes, if it works really well, there’s a time when the reader says, “Yeah, yeah, this is real,” and then has that “couldn’t possibly be.” One of the most rewarding moments was at a book club when I was talking with people about Herb ‘N’ Lorna. And after all discussion was over, and we were having coffee and pastries, a woman said, “I just have to confess something. Because this is really hard for me to admit this. But until about ten minutes into your talk, I thought this was all real. I thought this was a biography of two people.” So that was success.

BSS #269: Eric Kraft, Part Two (Download MP3)

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Huston: Sometimes, if you use the same words, you can put a little tinkle of irony into it. In the fact that you describe him doing it exactly the way the person just told him. So you use the exact same words. It’s hard for me to answer questions about the writing that are that precise. Because so much of the process is not that precise for me. So much of it is shoveling. And you’re not too terribly conscious of how you shovel while you’re doing it. Whether you’re good at it or not.

Huston: Sometimes, if you use the same words, you can put a little tinkle of irony into it. In the fact that you describe him doing it exactly the way the person just told him. So you use the exact same words. It’s hard for me to answer questions about the writing that are that precise. Because so much of the process is not that precise for me. So much of it is shoveling. And you’re not too terribly conscious of how you shovel while you’re doing it. Whether you’re good at it or not.

Correspondent: Fariba’s birth certificate is fake, you note later on in the book.

Correspondent: Fariba’s birth certificate is fake, you note later on in the book.

Correspondent: You quibble with the term “diagnosis.” You write, “There are no diagnoses in psychiatry. Only umbrella terms for observed patterns of complaint, groupings of symptoms given names, and oversimplified, and assigned what are probably erroneous causes because these erroneous causes can be medicated. And then both the drug and the supposed disease are made legitimate, and thus the profession as well as the patient legitimized, too, by those magical words going hand in hand to the insurance company ‘Diagnosis’ and ‘It’s not your fault.’” But if there are no diagnoses in psychiatry, well, where is the starting point? I mean, obviously, you have to start somewhere and identify a particular problem — even on a simplistic level — in order to help another person. So what of this?

Correspondent: You quibble with the term “diagnosis.” You write, “There are no diagnoses in psychiatry. Only umbrella terms for observed patterns of complaint, groupings of symptoms given names, and oversimplified, and assigned what are probably erroneous causes because these erroneous causes can be medicated. And then both the drug and the supposed disease are made legitimate, and thus the profession as well as the patient legitimized, too, by those magical words going hand in hand to the insurance company ‘Diagnosis’ and ‘It’s not your fault.’” But if there are no diagnoses in psychiatry, well, where is the starting point? I mean, obviously, you have to start somewhere and identify a particular problem — even on a simplistic level — in order to help another person. So what of this?