(This is the thirty-sixth entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: Of Human Bondage.)

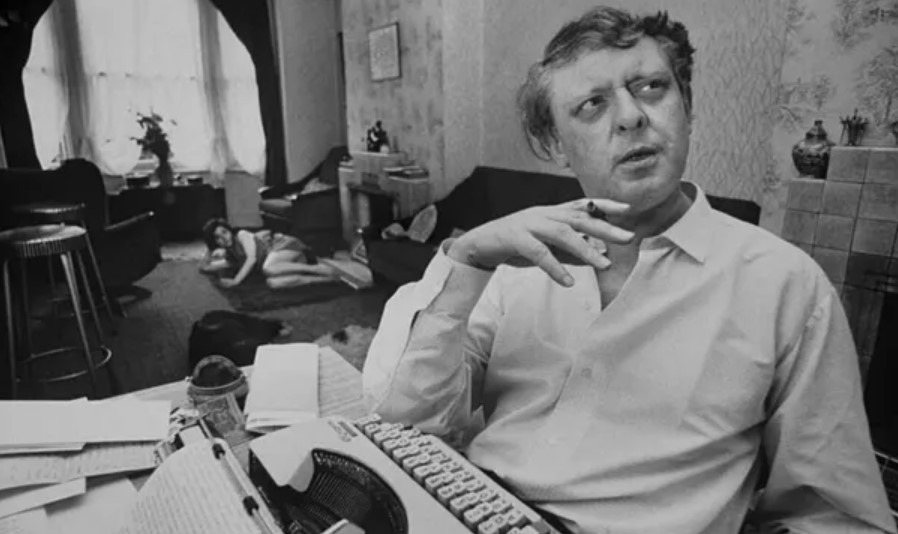

It’s become quite fashionable to bash the ridiculously prolific and mock pompous Mancunian with the combover. Never mind that anyone with a remote familiarity for how theatre comes together recognizes that Anthony Burgess perfected a magnetic if abrasive persona, frequently appearing on television with the likes of Dick Cavett when he wasn’t banging out his daily 1,000 words and, over the course of his life, appearing in every magazine known to humankind. (There’s a great joke in Alan Hollinghurst’s The Line of Beauty in which Nick Guest sees his article placed behind Burgess.) Burgess was a ferocious polymath who claimed to pick up languages in weeks and even devised the prehistoric patois for Quest for Fire. He was a composer and a provocateur who was sensible enough to find an instinctive way to piss off everyone: an old school virtue that is increasingly at odds with our age and that has the unintended consequence of stifling truths we need to talk about. He was the type of British writer who was catnip to a budding young California punk like me. Much like the equally neglected filmmaker Lindsay Anderson, he combined erudite anarchism with a gentle and often curiously lugubrious propriety. (I don’t think it’s an accident that Malcolm McDowell was both an Anderson staple and starred in Kubrick’s version of A Clockwork Orange.) One doesn’t see too many artists like this anymore on either side of the Pond.

It’s become quite fashionable to bash the ridiculously prolific and mock pompous Mancunian with the combover. Never mind that anyone with a remote familiarity for how theatre comes together recognizes that Anthony Burgess perfected a magnetic if abrasive persona, frequently appearing on television with the likes of Dick Cavett when he wasn’t banging out his daily 1,000 words and, over the course of his life, appearing in every magazine known to humankind. (There’s a great joke in Alan Hollinghurst’s The Line of Beauty in which Nick Guest sees his article placed behind Burgess.) Burgess was a ferocious polymath who claimed to pick up languages in weeks and even devised the prehistoric patois for Quest for Fire. He was a composer and a provocateur who was sensible enough to find an instinctive way to piss off everyone: an old school virtue that is increasingly at odds with our age and that has the unintended consequence of stifling truths we need to talk about. He was the type of British writer who was catnip to a budding young California punk like me. Much like the equally neglected filmmaker Lindsay Anderson, he combined erudite anarchism with a gentle and often curiously lugubrious propriety. (I don’t think it’s an accident that Malcolm McDowell was both an Anderson staple and starred in Kubrick’s version of A Clockwork Orange.) One doesn’t see too many artists like this anymore on either side of the Pond.

It would be tempting to suggest that Anthony Burgess’s wildly pugnacious, spectacularly bitter, and inarguably pathetic biographer Roger Lewis had something to do with this state of affairs, though that would be ascribing too much credit to this spiteful little worm, the living embodiment of what Joyce called a “biografiend.” (Lewis’s book, incidentally, is the worst and nastiest literary biography I have ever read. This is not a recommendation. It isn’t even enjoyable as a hate read.) Speaking ill of Burgess has become something of an unspoken duty among literary nerds ever since the erstwhile John Wilson bit the big one in 1993. When I interviewed Will Self in 2007 and mentioned Burgess, Self’s eyes lit up with the blood-curdling rancor of Van Helsing spotting Dracula and he called Burgess a “monster” with deep solemnity. Another literary writer, a MacArthur fellow, told me off the record that he detested Burgess with all of his heart. Even the mild-mannered blokes behind the terrific podcast Backlisted have gently condemned Burgess from time to time.

But I’ve always taken a shine to Burgess — in large part because I have always been deeply fond of arcane words, larger-than-life personalities who rub anyone owning more than three pair of pants the wrong way, and iconoclastic ambition within artists. Earthly Powers and the Enderby books, in particular, are great literary achievements, though their bloom has been dulled by the fact that mid-to-late career Burgess worked in a peculiarly learned comedic mode. You could argue, and many have, that Burgess was operating in the great shadow of Joyce, whom he greatly revered. Burgess wrote two entertaining (though somewhat lightweight) books on the great Irish genius: Joysprick and Re Joyce. And I suspect that this literary alignment has allowed me to forgive his more venomously obnoxious moments, which include insulting Graham Greene, accepting a Male Chauvinist Pig of the Year Award from a feminist press, and causing a cockalorum like Roger Lewis to waste many forlorn years of his go-nowhere life detesting him. (Fortunately, the more even-keeled Andrew Biswell has graced us with The Real Life of Anthony Burgess. And there are two volumes that Burgess himself wrote: Little Wilson and Big God and You’ve Had Your Time, both of which are hilarious collections of grandiose lies delivered with Burgess’s trademark self-importance.)

What’s most curious about A Clockwork Orange is how Burgess himself disowned it — even as he wrote introductions, made television appearances, and even quietly adapted into a musical. Throughout his life, Burgess felt he had “a sort of authorial duty to it.” Burgess resented not being known for his other works, but, given how regularly he stumped for M/F, a literary puzzle that has not held up very well, one suspects that Burgess himself was not his best critic. (Indeed, in April 1963, Burgess reviewed his own novel, Inside Mister Enderby, which was originally published under the name Joseph Kell. He gave a bad review to one of his most enjoyable books and lost his position at the Yorkshire Post over this mischief.)

A Clockwork Orange doesn’t fit tidily next to the humorous name-dropping flaunt of Earthly Powers‘s Kenneth Toomey or even the satirical dystopia of The Wanting Seed, in which heterosexuality is taboo in an effort to curb the global population rate. It is something else entirely: a pre-Riddley Walker exercise in invented slang (known as NADSAT) that is smoothly discernible (likely because Burgess was, by all reports, an excellent teacher), an examination of free will and moral agency, and an often disturbing portrait of Alex, a fifteen-year-old thug who casually kills, rapes, and/or assaults the homeless, some poor bastard who regularly checks out crystallography books from the local library branch, and ten-year-old girls. To this very day, there are many who find Kubrick’s largely faithful film adaptation disturbing, but the novel is probably more unsettling — in large part because we have to imagine all the violence, which is framed within the context of a decadent “modern age” that, much like Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, is set “somewhere in the 20th century.”

Kubrick needed Malcolm MacDowell’s charm to carry the picture. But Burgess kept you reading by way of the hypnotic slang. But even an adult character like Deltoid, who punctuates his speech with endless yeses, reads as if it was specifically written for Aubrey Morris, who is brilliantly hilarious in Kubrick’s film. One doesn’t need a glossary to divine that “veck” is man or that “slooshy” is to listen or that “gulliver” is head because Burgess’s context is grammatically precise. And while anyone tackling the likes of Russell Hoban or Finnegans Wake is likely to throw these two masterpieces against the wall at some point, the sense of discovery in A Clockwork Orange (to say nothing of the modest length) makes the reading experience far more pleasurable — even when one is also contending with a monstrously violent protagonist who sharpens his savage instincts with drugged milk and leads three droogs to rip up public seats and assault and pillage anyone in sight. Burgess’s argot has the added benefit of bolstering the modest weaknesses of the novel. If A Clockwork Orange had been written in traditional English, then some of the more pat observations about self-serving government officials (in this case, the Minister of the Interior or the Inferior and his accomplice Dr. Brodsky, who, justifying the Ludovico technique that makes Alex recoil against violence, says, “We are concerned only with cutting down crime”) and the choice to be violent may not have landed as well. But even a reader drawn to Burgess’s lexical allure needs a breather from time to time. And Burgess seems to intuitively know when to break up the flow with his adult characters. So when the writer F. Alexander — who shares Alex’s name, though as a surname, suggesting how ubiquitous a thirst for violence is — tells Alex, “But the essential intention is the real sin. A man who cannot choose ceases to be a man,” Burgess is better able to sell this because of the contrast with the main language.

And while one might quibble over why there isn’t a single character in this book other than the prison chaplain who doesn’t seek some form of revenge, Burgess, writing in 1962, is remarkably prescient on what awaits the world. Of the swastika, Alex describes it as “a Nazi flag with that like crooked cross that all malchicks at school love to draw.” And while such an idea was horrifyingly unthinkable less than two decades after the end of the second world war, recent headlines demonstrate that Burgess is merely “reporting” from the future. The rundown apartment block where Alex lives with his “P and M” could pass for a contemporary housing development in a rundown part of town: it is defaced with graffiti and has an elevator that doesn’t work. Just five years before the Beatles televised “All You Need is Love” in front of a worldwide television audience, Burgess depicts “worldcasts,” “meaning that the same programme was being viddied by everybody in the world that wanted to, that being mostly the middle-aged middle-class lewdies.” In 2023, these “worldcasts” immediately remind anyone of today’s relentless live streaming. What would Burgess have made of Twitter or TikTok?

Burgess also anticipated certain Dirty Harry criminological attitudes that, as evidenced by the merciless trolls I fend off daily on TikTok, are still quite popular with today’s reactionaries. Forgiveness? Hell no! A prisoner must still be vilified after he has “done his time.” And even when he is “cured” through conditioning, he’s still suspect. Or, as Dr. Brodsky, the head of the Ludovico Technique, puts it:

What a change is here, gentlemen, from the wretched hoodlum the State committed to unprofitable punishment some two years ago, unchanged after two years. Unchanged, do I say? Not quite. Prison taught him the false smile, the rubbed hands of hypocrisy, the fawning greased obsequious leer. Other vices it taught him, as well as confirming him in those he had long practised before. But, gentleman, enough of words. Actions speak louder than. Action now. Observe, all.

Later, the lodger Joe observes of Alex, “He’s weeping now, but that’s his craft and artfulness.” Throughout all this, Alex paints himself as a victim. Bereft of his criminal tyranny, and the ability to act upon it, he is “a victim of the modern age,” reduced to suicidal ideation.

Of course, we must remember that this novel is being told exclusively from Alex’s first-person perspective and is thus unreliable. While we can plausibly believe that Alex murdered the cat-happy baboochka, which sends him to prison — given how frequently he reflects on it — can we fully believe that the drinks that Alex and his droogs bought for the Duke of New York regulars from the “pretty polly” they stole were received with the great cheer he describes? Did he really pick up two ten-year-olds from the Melodia? Were the scientists truly that callous? We can’t know for sure. And these ambiguities create a fascinating tension that roils just as loudly as the NADSAT. And this is decades before cyberpunk. On the other hand, Alex does tell us that “this biting of their toe-nails over what is the cause of badness is what turns me into a fine laughing malchick. They don’t go into the cause of goodness, so why of the other shop?” (Emphasis in original.) Perhaps this is another way that Alex justifies his criminal behavior after the fact. But he does have a point about how happiness is usually accepted in our world without exegesis.

The most repeated phrase in A Clockwork Orange is “the heighth of fashion.” And that is no accident. Much like a child with a case of the giggles putting on grown-up clothes in a fitting room, Alex yearns to be a man and actually does possess some manners, such as beating the shit out of his fellow droog Dim when he is rude to a singer. If Burgess seriously believed that all people are naturally violent, then how often are our true instincts hiding beneath that civilized veneer? It’s no wonder why this novel appealed to Kubrick so much. Alex is as fond of classical music as he is of violence, longing for “a big feast of it before getting my passport stamped, my brothers, at sleep’s frontier.” And this contrast still feels disconcerting in the 21st century.

One other great detail about A Clockwork Orange that rarely gets commented upon is how the street names reference authors. There’s “Kingsley Avenue,” named after Amis, “Wilsonway,” named after Burgess’s real name, Boothby Avenue, Priestly Place, and so forth. (Roger Lewis has jumped off from this to suggest Clockwork is a sinister codex.. In one of many signs of his decidedly unbalanced scholarship, Roger Lewis puts forth the dodgy conspiracy theory that Burgess collaborated with a CIA officer named Howard Roman to secretly reveal mind control experiments conducted by the government. Lewis’s “source” — an apparent spook he met on a public bench who may have just been some lonely dude who wanted to talk to someone — claims that “the capitalized lines on page twenty-nine of A Clockwork Orange give the HQ location of the pschotronic warfare technology.” I suppose that, if you stare at any great novel long enough, you’ll create your own Pizzagate.)

Burgess also has a great deal of fun inventing fictitious composers and bands. The teenyboppers at the Melodia listen to Johnny Zhivago. (And indeed the New Wave band Heaven 17 took its name from Burgess.) Alex doesn’t just listen to “Ludwig Van.” He’s also a fan of Friedrich Gitterfenster’s opera Das Bettzeug. (And I’m sorry. But if you don’t snicker at least a little over the name “Gitterfenster,” then you have no soul.) Or how about Otto Skadelig? “Skadelig” is “harmful” in Norwegian. All this madcap invention gives A Clockwork Orange an incongruously urbane feel despite all the invented Cockney-Russian slang.

These fecund imaginative details transform A Clockwork Orange into one of the rare old novels that has aged far better that Burgess could have ever predicted (and to his great regret). Much like Knut Hamsun’s Hunger (published in 1890!), you can read A Clockwork Orange at any point in history and still feel as if it was written in the last decade. That’s not an easy trick for any author to pull off. And, if he did indeed write this in three weeks, it’s one very big reason why Anthony Burgess deserves a lot more respect for his literary achievements.

Next Up: J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye!