A few weeks ago, I stumbled onto an extraordinary audio drama called The Bright Sessions and listened to every episode with a speed and an enthusiasm rivaling a ravenous rabbit discovering a carrot field. The podcast is ostensibly a psychotherapist secretly recording her therapy sessions with young people, with each tape labeled with a mysterious taxonomic nomenclature. We come to learn that not only do these young people have special powers (the ability to jump through time, the capacity to read other people’s thoughts, et al.). But what makes The Bright Sessions so compelling is its more intimate approach. You won’t hear New York City destroyed in grandiloquent fashion after a superhero battle. But you will delve deep into the hearts and souls of the show’s characters.

I contacted the show’s creator Lauren Shippen (she also voices one of the patients, Sam) to express my appreciation and soon found myself in a fun and lengthy email volley about how Shippen came to create The Bright Sessions, thoughts on what radio drama can do for genre that other forms can’t, and some discussion of the 1985 film Clue. In tribute to the hashtag #audiodramasunday, which has recently taken Twitter by storm, I’m hoping this will be the first in a series of Audio Drama Sunday interviews with radio drama creators and their programs to help listeners and producers alike get a sense of the marvelous offerings out there.

If you want to listen to The Bright Sessions, go the website. You can also chip into The Bright Sessions‘s Patreon fund, which greatly helps this show stay afloat.

EDWARD CHAMPION: In audio drama, we have quite a number of wonderful podcasts being made that deal with investigations — what I call the “missing tapes” genre (The Black Tapes, Tanis, Limetown, et al.). These shows have responded, perhaps knowingly or unknowingly, to Serial‘s great success. It’s almost as if audio drama needed its own spin on the “fake documentary” style pioneered by such television shows as The Office, Parks & Recreation, and the like. But somehow your hook, which involves a psychologist taping the sessions of her clients, manages to transcend the tropes. I’m very curious to know how much you researched the audio drama climate before you started creating this show and if you learned any lessons on how to build an audience from your potential investigation. Also, I’m not sure how steeped you are in Dr. Jacob L. Moreno‘s notion of drama therapy, but where did your interest in psychotherapy come from? Why did you feel psychotherapy would be a great format for radio? (I’m also wondering if you’ve ever listened to the podcast, The Psychology of Eating, an often inexplicably fascinating show that deals with patients talking about their eating habits.)

LAUREN SHIPPEN: I actually wrote the first episode of The Bright Sessions in June of 2014 — before even Serial had been released. While I love the faux-documentary format of those podcasts (and of course, adore Serial), that trope didn’t yet exist when I first came up with the concept of The Bright Sessions. Instead, it was somewhat inspired by two very different radio shows: Welcome to Night Vale and BBC’s Cabin Pressure.

I was listening to these shows while stuck in the famed LA traffic and fell in love with the idea of audio drama. These shows showed two very distinct, very different paths to take: Welcome to Night Vale is mostly one man speaking into a microphone and Cabin Pressure is a whole cast with a large production budget performing in front of a live audience. As much as I enjoy Cabin Pressure, I don’t have the same resources as the BBC; the WTNV route seemed more manageable — I had a nice microphone and a vague idea of editing. But I ultimately realized I couldn’t pull off what WTNV does. I think WTNV works as a largely one person show because of three things: Cecil Baldwin’s performance, the beautifully surreal but funny writing, and the music by Disparition. Without a similarly magical combination of things, one person talking can get boring fast.

I wish I could say the therapy concept came out of some deep, clever thought process but – if memory serves – I was sitting in the aforementioned traffic, talking out loud to myself as the character of Sam (this is a weird but important part of my writing process) when I realized I needed to give her someone to talk to. The first thing that popped into my head was “therapist” and from there, the floodgates opened and everything started to fall into place.

I wish I could say the therapy concept came out of some deep, clever thought process but – if memory serves – I was sitting in the aforementioned traffic, talking out loud to myself as the character of Sam (this is a weird but important part of my writing process) when I realized I needed to give her someone to talk to. The first thing that popped into my head was “therapist” and from there, the floodgates opened and everything started to fall into place.

I wrote that pilot episode in essentially one sitting. Then I got swept up in other things and didn’t touch it for a year. By the time I came back to it, I had become more familiar with the audio drama landscape as a whole. I had binged Serial, Limetown, and The Message. But my format was already determined. That being said, I did look to these and other shows to see how and where they existed online and how they promoted themselves.

I’m tangentially familiar with Moreno’s work, but The Bright Sessions was not particularly influenced by any one psychological theory. I used my sister — an actual psychologist — as a resource for how a therapist would talk or what methods they might use and did online research when necessary. I think my interest in psychotherapy actually comes from my background as an actor. The conversations you hear in the podcast are very similar to internal conversations I will have when developing a character – you have to figure out all their baggage, what makes them tick. Bizarrely, a lot of acting techniques are pretty similar to therapeutic ones, so it was easy to connect the dots.

I think the therapy format works especially well on radio for two reasons. One: it’s straightforward and easy to follow. It can be hard to pull off convincing action in an audio format, but it’s very easy to put together two people having a conversation. Two: there’s a voyeuristic element to it that I think is intriguing to people. Even though our patients are extraordinary, they are still dealing with very real, human problems. I think there’s a lot of entertainment to be mined out of that and a lot to relate to. And because it’s an audio recording and not a video, I think it gives the listener the feeling that they are really there, listening in.

I think the therapy format works especially well on radio for two reasons. One: it’s straightforward and easy to follow. It can be hard to pull off convincing action in an audio format, but it’s very easy to put together two people having a conversation. Two: there’s a voyeuristic element to it that I think is intriguing to people. Even though our patients are extraordinary, they are still dealing with very real, human problems. I think there’s a lot of entertainment to be mined out of that and a lot to relate to. And because it’s an audio recording and not a video, I think it gives the listener the feeling that they are really there, listening in.

And no, I have not listened to The Psychology of Eating, though it sounds like something I need to put in my feed!

CHAMPION: On the subject of psychotherapists, I think one of the reasons your audio drama works so well is because Julia Morizawa is tremendously believable as Dr. Bright. We often hear an annoyed edge in her voice, a vague artificiality often vacillating with something real, with the slight pause just before she has to enter into that professional therapeutic mode. I’m so glad that your audio drama is paying attention to these minute cadences, whether deliberately or organically. It’s one of the aspects of therapy that can be irksome when you’re on the couch! And it leads me to wonder what work you did with Julia to hit these very precise notes and what prep you’ve done with your actors in general. Of course, what I’m detecting here may very well be the natural intimacy of radio! After all, if you listen to any of Anna Sale’s interviews on Death, Sex & Money, it often sounds like a therapy session. Why do you think the radio format lends itself more to a therapeutic vibe? Should audio drama be hitting this sweet spot if it expects to win over larger audiences? Also, how did these conversations with yourself in traffic contribute to the writing process you worked out?

SHIPPEN: Julia is a magical superhuman and The Bright Sessions would not be a tenth of what it is without her. That sounds like hyperbole; it isn’t. I’ve known Julia for about two years – we met in acting class at the BGB Studio in North Hollywood. That same studio is where I met Briggon Snow (Caleb) and Charlie Ian (Damien) — it’s a studio full of crazy talented people and I take as much advantage of that as possible. The moment I realized I didn’t want to play Dr. Bright myself (and yes, that was something I briefly flirted with), my mind immediately went to Julia.

I wish I could take credit for all the nuances that Julia brings to the role but all the layers and subtle shifts you hear are a testament to Julia’s talent as an actor. We certainly discuss the character and the story; I give my impressions and Julia always comes prepared with insightful questions and ideas. The first time we recorded, she lugged this enormous binder with her — it had the scripts, her own personal character biography, and pages of notes. Her dedication and attention to detail has made Dr. Bright an incredibly interesting and complex character and really changed the way I approached the writing her. No one, including myself, knows Dr. Bright better than Julia and I think that shines through.

I wish I could take credit for all the nuances that Julia brings to the role but all the layers and subtle shifts you hear are a testament to Julia’s talent as an actor. We certainly discuss the character and the story; I give my impressions and Julia always comes prepared with insightful questions and ideas. The first time we recorded, she lugged this enormous binder with her — it had the scripts, her own personal character biography, and pages of notes. Her dedication and attention to detail has made Dr. Bright an incredibly interesting and complex character and really changed the way I approached the writing her. No one, including myself, knows Dr. Bright better than Julia and I think that shines through.

On the whole, I don’t do much prep with my actors. I honestly don’t even give them that much direction when we record. They are all very talented people that I have worked with before and I trust their instincts. I’m still amazed I was able to convince these brilliant people into doing this little project — I really feel like I have an embarrassment of riches when it comes to our cast.

Our especially dedicated listeners (of which we have more than I could have dreamed — another embarrassment of riches) will be familiar with the music playlists I made for each character. While these have been very fun to share with our audience as bonus features, I made them for myself as a writing tool and for my actors as a way to round out the characters for them. While we were recording the first season, I shared these playlists as well as Pinterest boards. While not directly related to the plot, these were used to express some of the less tangible aspects of the characters.

Our especially dedicated listeners (of which we have more than I could have dreamed — another embarrassment of riches) will be familiar with the music playlists I made for each character. While these have been very fun to share with our audience as bonus features, I made them for myself as a writing tool and for my actors as a way to round out the characters for them. While we were recording the first season, I shared these playlists as well as Pinterest boards. While not directly related to the plot, these were used to express some of the less tangible aspects of the characters.

I think the phrase you used, “the natural intimacy of radio”, is exactly why it lends itself to the therapeutic feeling. With radio, the listener can imagine whatever they want about how the person looks, what the setting is like, etc. This engagement of the imagination engages us emotionally as well and creates this atmosphere of intimacy. I think this is furthered by the fact that most people listen to podcasts alone, with headphones on. It feels personal in a way that TV or film doesn’t. As for an audio drama sweet spot, I’m still trying to find that myself.

The traffic conversations have been a big part of my life in LA and I’m sure have gotten me a few strange looks at stoplights. When I’m working on a character — whether it’s one I’m auditioning for or one I’m creating from the bottom up — I have to determine some things about how they talk. Where in my voice does their dialogue sit? What’s their cadence? What filler words do they use? This can all be worked out on paper or in a script, but I find it’s much easier to work through this process out loud.

So, when I’m doing a task that is taking up most of my focus — driving, cooking, doing dishes — I’ll pass the time by having imaginary conversations with these characters. Some of these conversations simply help me get into the mindset, but some end up in the final product. I think I was able to write that first episode in one sitting because I had worked out most of it in the car when driving back from Santa Monica during rush hour (never do this).

CHAMPION: I’m tremendously fascinated with the work you’re doing with the actors to establish these characters and very curious how, in this case, Julia’s notes altered the writing. How much of this story do you have planned out? And how much of the story has been dictated by the notes from the actors? What did these music playlists reveal about these characters that, say, unpacking a history and a backstory didn’t? Your filler description reminds me very much of how David Mamet layers his scripts with underlined emphasis and includes all these filler words or how someone like Kevin Smith is especially demanding of inflection points. My own feeling is that there’s a certain futility in this process. Because there isn’t a single writer, no matter how talented, who can completely transcribe human speech without the final artistic output sounding deliberately stylized. This can often take us away from the reality of what we’re experiencing — unless, of course, one is deliberately striving for a heightened reality. But it does raise some questions. Because no matter what the art, one does have to find a balance between reality and fiction. If we’re reading transcribed speech from Mark Twain or Emma Bovary’s inflections, our minds can fill in the details. But radio is more explicit about speech, even if we’re still using our minds to imagine what’s happening before us. How do your conversations in the car help you to find a compromise between some “authentic” blueprint and the organic nature of conversation that you end up recording?

CHAMPION: I’m tremendously fascinated with the work you’re doing with the actors to establish these characters and very curious how, in this case, Julia’s notes altered the writing. How much of this story do you have planned out? And how much of the story has been dictated by the notes from the actors? What did these music playlists reveal about these characters that, say, unpacking a history and a backstory didn’t? Your filler description reminds me very much of how David Mamet layers his scripts with underlined emphasis and includes all these filler words or how someone like Kevin Smith is especially demanding of inflection points. My own feeling is that there’s a certain futility in this process. Because there isn’t a single writer, no matter how talented, who can completely transcribe human speech without the final artistic output sounding deliberately stylized. This can often take us away from the reality of what we’re experiencing — unless, of course, one is deliberately striving for a heightened reality. But it does raise some questions. Because no matter what the art, one does have to find a balance between reality and fiction. If we’re reading transcribed speech from Mark Twain or Emma Bovary’s inflections, our minds can fill in the details. But radio is more explicit about speech, even if we’re still using our minds to imagine what’s happening before us. How do your conversations in the car help you to find a compromise between some “authentic” blueprint and the organic nature of conversation that you end up recording?

SHIPPEN: I had written the first nine episodes (which make up the first season) before we all sat down for the first table read. I had a clear idea of who these characters were and where I wanted the story to go. And then I heard it out loud, as interpreted by smart, talented people, and things shifted. I don’t want to go too much into what the initial overarching plot of The Bright Sessions was for fear of changing people’s perceptions of what it is now, but hearing Julia interpret the character of Joan Bright changed the way I thought of the character. She became more real, more human, and her motivations changed somewhat as a result. This shift changed a lot of other characters as well.

Similarly, our production meeting before season two provided a lot of inspiration. I shared the first few scripts and told the actors what I had in store. And then they shared their ideas about the characters and how they wanted them to grow. A lot of the plot for season two grew out of that. The finale episode of this season is a direct result of that production meeting and a few ideas that Charlie Ian floated around. A lot of The AM has been influenced by ideas that Julia has had. So, while I do all the actual writing, my actors absolutely deserve a lot of story credit for the second season.

Similarly, our production meeting before season two provided a lot of inspiration. I shared the first few scripts and told the actors what I had in store. And then they shared their ideas about the characters and how they wanted them to grow. A lot of the plot for season two grew out of that. The finale episode of this season is a direct result of that production meeting and a few ideas that Charlie Ian floated around. A lot of The AM has been influenced by ideas that Julia has had. So, while I do all the actual writing, my actors absolutely deserve a lot of story credit for the second season.

I don’t know what the music playlists revealed to the actors — that’s probably something I should ask them. For me, the mixes provide the general mood of the character; an energy. I listen to the mixes before writing the characters to get me in that mindset. It can also help me zero in on an overall theme within the character. For example, I built Sam’s whole playlist pretty quickly (she’s the character I voice so I know her very well) and afterwards I realized how much of the content had to do with the idea of “home.” That discovery told me a lot about the character and what was important to her.

I think you’re absolutely right — no writer can ever perfectly mimic natural speech. My use of filler speech, aborted starts to sentences, stutters, etc. function more as goal posts for the general speech pattern of the characters. Caleb says “like” a lot — he’s a teenager, he doesn’t always know how to express himself so he uses this filler word and doesn’t finish sentences sometimes. Sam has a lot of ellipses in her speech. She’s a nervous person so she stops to think of the right…word. I’ll write these kinds of things into the script and then the actors will adopt them and put them in the natural places, even when they aren’t written in. Then it becomes a volley between me and the actor — I write something, they improv and ad lib, I adopt those natural inclinations into writing the next time, so on and so forth.

The car conversations are vital in the early stages of developing a character. I can try and write out their speech patterns but it won’t solidify until I start saying it out loud. There are things that will look good on paper but sound stilted or unnatural when spoken aloud. And then there are questions that need to be answered. Does the speech go up at the end — if so, how would that affect the way they structure their sentences? Where do they pause? Why do they pause? Do they have to fill the pause with speech or can they sit in silence? All of these questions need to be answered and are easiest when worked through out loud. I don’t often return to these car conversations after I’ve gotten used to writing a character. Thought they can be helpful for figuring out how two characters who have never met talk to each other because each character relates to every other character in a unique way and that is going to change their speech.

CHAMPION: Aha! So as I suspected, your actors almost serve as “editors” for your scripts! This leads me to ask how you manage all the very helpful input you get from your talent. This may be tangentially related to the issue of natural vs. stylized speech, but have you ever faced a situation where your vision for the storyline gets disrupted by all the ideas from others? If so, how do you manage all the notes? How locked is the script when you eventually record it? Also, how and where are you recording it? Given that the patients are teenagers, I’m wondering if you ever considered using actual teenagers for the part. Aside from the car conversations and your work with the actors, do you talk to a lot of high schoolers to get a sense of their angst? (I’m thinking especially of Caleb and the adept way you handle his sexuality.) Given that you seem to be responding to what you have previously established with each episode, what steps have you taken to ensure that you never get caught up in tropes or predictable storylines? Do you have a natural end point in mind for The Bright Sessions?

SHIPPEN: The input from actors never feels too overwhelming or disruptive because it comes in bits and pieces. I’ll send out a script and get some questions and comments back and then I’ll make small adjustments to the script. A lot of the larger ideas come from “wouldn’t it be cool if” conversations about the overarching plot or character development. An actor will make a suggestion or float an idea about what could potentially happen in a season or in an episode and, if it works, I’ll take that suggestion and work it into the existing structure. As the sole writer of the podcast, all the details and specifics are up to me.

When we record, the script is 98% locked in, I’d say. It’s a final draft (that never seems to stop it from having typos) but occasionally an actor will ad lib or ask to say a line a slightly different way. But, beyond from a few minor line changes or improvs, the scripts tend to be consistent from page to episode. Editing also sometimes happens in post-production – I’ve cut out lines in the past that worked on the page but didn’t in the editing bay.

With a few exceptions, we record the episodes with both actors sitting across from each other, with individual mics on them. We go through the episode in it’s entirety a few times as I give notes. It’s a lot like acting in a class — we’re not crammed into a sound booth recording each line one-by-one — instead we’re recording the episode pretty much as it would happen in real life: two people sitting in a room together (my bedroom in this case — we’re very high tech).

Technically, only one of the patients is a teenager: Caleb. Adam is also in his teens, though not a patient, and Chloe is 20 when the series begins, so only just over that period in her life. But no, I never considered using actual teenagers. Firstly, there would be a lot of logistical and practical issues recording with someone under 18 and secondly, I never considered anyone other than Briggon for the role of Caleb. And he has nailed the high school voice, as I knew he would.

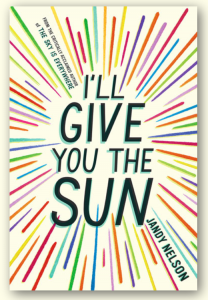

I honestly can’t remember the last time I talked to a teenager — I wish I could say I’ve done in-person research, but most of Caleb’s plot line is directly inspired by all the YA novels I read. Yes, I do still read Young Adult fiction. I’ve met my fair share of adults who don’t consider that a good use of time, but I politely disagree. YA fiction is consistently growing and changing and there are some real gems to be found. I read a lot, and in a lot of different genres, and one of the best things I’ve read in the past few years is I’ll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson. It is a book that I couldn’t put down and it has lingered in my mind ever since. I think it has had a lot of influence on the writing of both Caleb and Chloe and I can’t recommend it enough.

I honestly can’t remember the last time I talked to a teenager — I wish I could say I’ve done in-person research, but most of Caleb’s plot line is directly inspired by all the YA novels I read. Yes, I do still read Young Adult fiction. I’ve met my fair share of adults who don’t consider that a good use of time, but I politely disagree. YA fiction is consistently growing and changing and there are some real gems to be found. I read a lot, and in a lot of different genres, and one of the best things I’ve read in the past few years is I’ll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson. It is a book that I couldn’t put down and it has lingered in my mind ever since. I think it has had a lot of influence on the writing of both Caleb and Chloe and I can’t recommend it enough.

I also spend a lot of time on Tumblr, a website that definitely skews towards a younger audience. There’s actually quite a bit of linguistic discussion that happens on the site and I think I’ve absorbed a lot about how teenagers speak and interact. On top of that, I read fan fiction — not of The Bright Sessions, but of other things. Fan fiction is written about and by many different people, but a good portion of it either explores the lives of teenagers or is written by teenagers. Reading teenage dialogue written by a teenager will give you a pretty good idea of what teenagers sound like. So I think my ability to write compelling high school dialogue is a combination of reading YA fiction, reading fan fiction, and observing teenagers on social media.

This actually transitions well into your question about tropes. A lot of fandom conversation and fan fiction is centered around the idea of tropes — either leaning into them or breaking them. In order to avoid tropes, you have to know what they are. And yes, you can watch a lot of film and television, listen to a lot of audio drama, and read a lot of books to get an idea of what the cliches are but it is helpful to have tropes distilled for you. That’s what happens in fandom discussion.

All that said, I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about making things unpredictable. I focus on what stories I want to tell and sometimes that means taking a hard left and sometimes that means jumping directly into a trope – after all, cliches are cliches for a reason. But, to keep things engaging, it’s important to make a slight tweak when engaging with tropes. The Bright Sessions is built on this idea. A mysterious time traveler shows up! But…she can’t control her ability. A high school football player is having trouble expressing his emotions! But…not for the usual reasons. I think it’s really fun to lean into story beats that are familiar but give them a different flavor.

As for keeping the plot from getting predictable, I think it’s a delicate balancing act. A certain amount of predictability is a good thing, in my opinion. When I see a listener comment with a prediction about the plot, I’m pleased if that prediction is very close to correct. That tells me that I’m on the right path, that I’m not going to jump the shark. However, you don’t want your audience to be able to predict everything. And that’s where the red herring comes in (Clue is one of my all-time favorite movies and I’ve had to delete an entire paragraph explanation of why because this isn’t my chance to write a dissertation of Clue). Currently, I’m seeing a lot of predictions about the end of season two that could be correct. The predictions make sense in the context of what has happened so far but they are largely in response to something that is a bit of a red herring. As a result, I think the end of the season is going to be unexpected at the time and make complete sense looking back (that’s my hope anyway).

As for a natural end point for The Bright Sessions…no, I don’t have one. I’ve heard a lot of other audio drama creators say “I know exactly what the last episode/last line/last season of my podcast is” – I am not that person. I had no idea how this season was going to end when I started it. I know where I would like characters to end up emotionally but I’m really just letting this thing organically develop on its own terms. We’ll see where that takes us.

CHAMPION: Your method of scouring for youthful banter reminds me of how the great novelist Megan Abbott conducts research. She also writes about young people very well and scours many online forums to get the tone right for her last few books. But I’ve detected a bit of Alfred Bester and Theodore Sturgeon in The Bright Sessions. I’m curious to know more about The Bright Sessions‘s literary influences (including YA, of which, being a wide reader myself, I’m certainly not going to pull a Ruth Graham here!). Also, we’re living in a time in which we are saturated by endless superhero movies, Hugo Awards ballot stuffing by frightened white middle-aged libertarians, Comic-Con as a publicity machine, fan entitlement, and numerous other intrusions into genre storytelling. But the many genre audio drama podcasts I listen to — such as yours, Ars Paradoxica, Atheist Apocalypse, Tanis, Lily Beacon, Wolf 359, Eos 10, The Cleansed, far too many wonderful shows to list here — seem relatively insulated from these developments. It’s almost as if audio drama is operating in its own hermetic corner, relatively safe from any General Zod neck-snapping controversies. Do you think audio drama runs the risk of getting co-opted? Or capitulating to the audience too much? What do you feel you owe the audience? Do you think audio drama is enough of its own animal to beat the odds? And why (or why not) do you think that is?

SHIPPEN: I think it’s hard to say what’s not a literary influence on The Bright Sessions — everything I’ve written could probably be traced back to something I read once. I am an avid reader and I feel like every book I read becomes a part of my brain. YA has definitely had a big influence, David Mitchell is always in the back of my mind when I’m thinking about world-building (especially on top of existing reality — he’s a master at that), and Philip Pullman (an all-time favorite of mine) has definitely had a roundabout influence on the last few episodes of this season (and on my brain in general).

I think audio drama is excelling in genre storytelling for a few reasons. Firstly, genre film and TV can often fall into the trap of focusing too much on the “smashy-smashy” (as NPR’s Glen Weldon calls it). While people, myself included, go to these films for action, it is sometimes given attention to the detriment of character or plot. Unless the action is innovative and exciting enough to hold up a film (as it is in Mad Max: Fury Road, though that movie has pretty much everything going for it, in my opinion), you can’t just blow up buildings (or have Superman snapping necks) and hope people will be satisfied.

Audio drama is truly incapable of making that specific mistake. Action can happen in audio form – the audio montage in Wolf 359‘s “Mayday” is a stellar example of this — but action isn’t the go-to. Instead, the focus goes to the characters and the worlds. When you can’t distract the audience with shiny effects or crazy stunts, you have to work twice as hard to give them something to chew on. I think that motivates audio drama to innovate a lot more than other mediums.

Secondly, I think audio drama benefits from being independently produced. It costs money to make a podcast, but not Mad Max $150 million kind of money. There’s no studio to appease, no execs to give notes, no 20 person marketing team ready to merchandise your idea. Having audio drama be entirely in the hands of its creators provides the kind of freedom you can’t find in big genre movies. As a result, you see a lot more risk-taking and a lot more diversity in audio drama. Half of the podcasts you mentioned have female protagonists; Marvel has yet to make a female-led movie. There have been numerous news stories recently about how female characters in genre films were changed to male for fear that a female character wouldn’t sell toys. Even when genre creators try their best to widen the pool of main characters — and I really do believe that they are trying — there is a larger machine at work that can stall progress. To my knowledge, that machine has yet to exist in audio drama.

I couldn’t presume to predict where the audio drama world is headed — I’m still a newcomer but I feel like things have shifted in the year I’ve been working on The Bright Sessions. There’s more content than ever and the quality of said content seems to be getting better and better. I think there will certainly be attempts to co-opt audio drama — after all, it is a rapidly growing entertainment sector with low overheads and excellent advertising potential — but I don’t know what form that will take or how successful those attempts will be. But, whatever happens, I think audio drama will continue to find new and exciting ways to tell stories, whether independently or under a larger umbrella. Bigger is sometimes better.

As for what I feel I owe our audience: I want to continue to entertain and surprise them. I want to keep things unpredictable without making them ever feel like they’ve been misled or cheated. I don’t think I owe rainbows and sunshine — the audience doesn’t have to like every plot point or character — but I owe thoughtful writing, even when it’s painful. I owe them continued and respectful character development, enthusiasm to rival their own, and a satisfying conclusion to a story they’ve invested in.

As to when that conclusion will come is anybody’s guess.

Correspondent: Well, going back to one of the many questions that I just asked you about the idea of concocting this alternative universe, was it a matter of working within a loose world here? I mean, in a way, this book reminded me very much of a Michael Moorcock alternative history, like the Hawkmoon books that he wrote, which have only a few existing elements which suggest what may have happened. But it’s largely an excuse. This particular book gave Moorcock the freedom to explore this notion of ideas that have spun off into other terribly mutated forms. And I wanted to ask how this idea of worldbuilding relates to this idea of exploring ideologies, of which I plan to ask you more about.

Correspondent: Well, going back to one of the many questions that I just asked you about the idea of concocting this alternative universe, was it a matter of working within a loose world here? I mean, in a way, this book reminded me very much of a Michael Moorcock alternative history, like the Hawkmoon books that he wrote, which have only a few existing elements which suggest what may have happened. But it’s largely an excuse. This particular book gave Moorcock the freedom to explore this notion of ideas that have spun off into other terribly mutated forms. And I wanted to ask how this idea of worldbuilding relates to this idea of exploring ideologies, of which I plan to ask you more about.