On Tuesday afternoon, the Associated Press’s Hillel Italie reported that a recently published spy novel — Q.R. Markham’s Assassin of Secrets — was being pulled after Markham’s publisher, Mulholland Books, had determined that Markham had lifted his text from other sources.

Reluctant Habits has obtained a finished copy of the Markham book. The following examples, compared from Markham’s book to the original sources, demonstrate just how much Markham (real name: Quentin Rowan) stole from other material.

* * *

Markham, Page 13: “His step had an unusual silence to it. It was late morning in October of the year 1968 and the warm, still air had turned heavy with moisture, causing others in the long hallway to walk with a slow shuffle, a sort of somber march.”

Taken from Page 1 of James Bamford’s Body of Secrets: Anatomy of the Ultra-Secret National Security Agency: “His step had an unusual urgency to it. Not fast, but anxious, like a child heading out to recess who had been warned not to run. It was late morning and the warm, still air had turned heavy with moisture, causing others on the long hallway to walk with a slow shuffle, a sort of somber march.”

* * *

Markham, Page 13: “The boxy, sprawling Munitions Building which sat near the Washington Monument and quietly served as I-Division’s base of operations was a study in monotony. Endless corridors connecting to endless corridors. Walls a shade of green common to bad cheese and fruit. Forests of oak desks separated down the middle by rows of tall columns, like concrete redwoods, each with a number designating a particular work space.”

Taken from Bamford, Page 1: “In June 1930, the boxy, sprawling Munitions Building, near the Washington Monument, was a study in monotony. Endless corridors connecting to endless corridors. Walls a shade of green common to bad cheese and fruit. Forests of oak desks separated down the middle by rows of tall columns, like concrete redwoods, each with a number designating a particular work space.”

* * *

Markham, Page 13: “Chase’s brown loafers made a sudden soundless left turn into a heavily deserted wing. It was lined with closed doors containing dim, opaque windows and empty name holders.”

Taken from Bamford, Page 1: “Oddly, he made a sudden left turn into a nearly deserted wing. It was lined with closed doors containing dim, opaque windows and empty name holders.”

* * *

Markham, Page 14: “…Chase mused, as he turned right into Room 32, a small office containing a massive black vault, the kind found in exclusive Swiss banks. Reaching into the front pocket of his gingham shirt, he removed a small card. Then, standing in front of the thick round combination dial, he began twisting it back and forth. Seconds later he yanked up the silver bolt and slowly pushed open the heavy door, only to reveal another wall of steel behind it. This time he removed a key from a small compartment inside the heel of his left shoe and turned it in the lock, swinging aside the second door to reveal an interior as bright and cheery as noonday sun.”

Taken from Bamford, Page 1-2: “Halfway down the hall Friedman turned right into Room 3416, a small office containing a massive black vault, the kind found in large banks. Reaching into his inside coat pocket, he removed a small card. Then, standing in front of the thick round combination dial to block the view, he began twisting the dial back and forth. Seconds later he yanked up the silver bolt and slowly pulled open the heavy door, only to reveal another wall of steel behind it. This time he removed a key from his trouser pocket and turned it in the lock, swinging aside the second door to reveal an interior as dark as a midnight lunar eclipse.”

* * *

Markham, Page 14: “Yet somehow, at forty-eight years old, Virginia-born Brewster had spent his entire adult life studying, practicing, defining the black arts of espionage and counterintelligence. Six years earlier, during the autumn of 1962, Brewster had been appointed the chief and sole employee of a secret new organization responsible for monitoring — ‘watchdogging,’ in the new president’s words — all of the other intelligence services: the CIA in particular.”

Taken from Bamford, Page 1: “At thirty-eight years old, the Russian-born William Frederick Friedman had spent most of his adult life studying, practicing, defining the black art of code-breaking. The year before, he had been appointed the chief and sole employee of a secret new Army organization responsible for analyzing and cracking foreign codes and ciphers. Now, at last, his one-man Signal Intelligence Service actually had employees, three of them, who were attempting to keep pace close behind.”

* * *

Markham, Page 15: “He was a natural administrator; he absorbed written material at a glance and never forgot anything. He knew the names and pseudonyms, the photographs, and the operative weakness of every agent controlled by Americans everywhere in the world. Brewster rarely met with any of them, and few of them knew he existed, but he designed their lives, forming them into a global subsociety that had become what it was, and remained so, at his pleasure. He was outranked by only three men in the American intelligence community.”

Taken from Charles McCarry’s The Tears of Autumn: “He was a natural administrator; he absorbed written material at a glance and never forgot anything. He knew the names and pseudonyms, the photographs and the operative weakness of every agent controlled by Americans everywhere in the world. Patchen never met any of them, and none of them knew he existed, but he designed their lives, forming them into a global sub-society that had become what it was, and remained so, at his pleasure. His hair turned gray when he was thirty, possibly from the pain of his wounds. At thirty-five he was outranked by only four men in the American intelligence community.”

* * *

Markham, Page 15: “The machine measured their breathing, the sweat on their palms, their blood pressure and pulse, and it knew whether they had stolen money from the government, submitted to homosexual advances, been doubled by the opposition, committed adultery. The test was called the ‘flutter.'”

Markham, Page 15: “The machine measured their breathing, the sweat on their palms, their blood pressure and pulse, and it knew whether they had stolen money from the government, submitted to homosexual advances, been doubled by the opposition, committed adultery. The test was called the ‘flutter.'”

Taken from Charles McCarry’s The Tears of Autumn: “The machine measured their breathing, the sweat on their palms, their blood pressure and pulse, and it knew whether they had stolen money from the government, submitted to homosexual advances, been doubled by the opposition, committed adultery. The test was called the ‘flutter.'”

* * *

Markham, Pages 15-16: “To Brewster, the heart attack machine was the ordeal of brotherhood. He believed that those who went through it were cold in their minds, trained to observe and report but never to judge. They looked for flaws in humanity and were never surprised to find them; the polygraph had taught Chase so much about himself — taught him that guilt can be read on human skin with a meter.”

From Charles McCarry’s The Tears of Autumn: “To Webster, the flutter was the ordeal of brotherhood. He believed that those who went through it were cold in their minds, trained to observe and report but never to judge. They looked for flaws in men and were never surprised to find them: the polygraph had taught them so much about themselves — taught them that guilt can be read on human skin with a meter — that they knew what all men were.”

* * *

Markham, Pages 16-17: “His number two agent wore large horn-rimmed eyeglasses, had dirty-blond hair that covered his forehead and the tops of his ears, was broad-shouldered but slim, and very handsome. His eyes were a warm blue and he had the kind of weather-beaten face that suggested years of outdoor activity. Chase almost had the look of an old-time matinee idol, but there was a certain quirkiness, a wistfulness, a rueful irony to his face that left a different kind of emotional trademark. An almost dandified alienation. This, Brewster guessed, was what had endeared his number two man to all those serious dark-haired women in Paris and Milan.”

Taken from two sources (1) Raymond Benson’s High Time to Kill: “Group Captain Roland Marquis was blond, broad-shouldered, and very handsome. A neatly trimmed blond mustache covered his upper lip. His eyes were a cold blue. He had the kind of weather-beaten face that suggested years of outdoor activity, and the square jaw of a matinee idol.” (2) Geoffrey O’Brien’s Dream Time: “The mark this leaves on him is not shame but rather the wistfulness of the spy, his self-indulgent rueful irony, an emotional trademark that endears him to serious dark-haired women in Brussels and Milan. They are attracted to the way he embodies a dandified alienation.”

* * *

Markham, Page 17: “Also, it was evident to Brewster from the day he met Chase in Korea that he was the finest natural spy he had ever encountered. There was no easy explanation for his talent. Perhaps the first reason for his excellence was his truculent refusal to believe in anybody’s innocence. Chase treated all men and women as enemy agents at all times; they could be used, paid, praised. They could be loved. But they could never be trusted. What might seem paranoia in another man was shrewd intuition in Chase.”

Taken from Charles McCarry, The Last Supper: “Also, it was evident to Hubbard from the day Wolkowicz arrived in Berlin that he was the finest natural spy he had ever encountered. There was no easy explanation for this talent. Perhaps the first reason for his excellence was his truculent refusal to believe in anybody’s innocence. Wolkowicz treated all men, and especially all women, as enemy agents at all times; they could be used, paid, praised. What might seem paranoia in another man was shrewd intuition in Wolkowicz.”

* * *

Markham, P. 18:: “They’re reportedly responsible for the theft of those military maps from Hanoi from the Pentagon last month. A well-protected Mafia don was murdered about a year ago in Cuba. Zero Directorate supposedly supplied the hit man for that job.”

Taken from Raymond Benson’s High Time to Kill: “The maps disappeared from right under the noses of highly trained security personnel. A well-protected Mafia don was murdered about a year ago in Sicily. The Union supposedly supplied the hit man for that job.”

* * *

Markham, P. 20: “Some even thought he operated outside the apparatus; in fact, he was implanted so deeply within it as to be more or less detached from its rules.”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “…he operated outside the apparatus; in fact he was implanted so deeply within it as to be detached from its rules.”

* * *

Markham, P. 20: “But what happens to the market if you can’t keep a secret, if you never know which one of your people is going to be grabbed next and given a shot of something that makes him want to tell everything he knows?”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “But what happens to the market if you can’t keep a secret, if you never know which one of your people is going to be grabbed next and given a shot of something that makes him want to tell everything he knows?”

* * *

Markham, P. 21-22: “It made him think of a warm autumn evening a year before the shooting of John F. Kennedy when the president preempted regular television programming to give advance notice of the possible erasure of the world. Chase had been walking down K Street when the neon was just coming on. People were walking around in the usual way. Never had ordinary gestures — buying a newspaper, putting the key in the lock, shoving a quarter across the counter at the luncheonette — seemed so submissive, so humiliated. Even if a more precise hour were fixed for the great dissolution, the hand would continue in automaton fashion to shove the coin across the counter.”

From Geoffrey O’Brien’s Dream Time: “A year before the shooting of John F. Kennedy, for instance, on a warm autumn evening the President preempted regular television programming to give advance notice of the possible erasure of the world. On the street the neon was just coming on. People were walking around in the usual way. Never had ordinary gestures — buying a newspaper, putting the key in the lock, shoving a quarter across the counter, waiting on line to see the new adventure movie — seemed so submissive, so humiliated. The people on the street had in any case no way of responding. Even if a more precise hour were fixed for the great dissolution, the hand would continue in automaton fashion to shove the coin across the counter.”

* * *

Markham, P. 22: “As Chase himself would say years later, when he knew him better than anyone alive, the old man decided everything between his pelvis and his collarbone. Chase meant this as a compliment: anyone could be an intellectual.”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “As Patchen himself would say years later, when he knew him better than anyone alive, the old man decided everything between his pelvis and his collarbone. He meant this as a compliment: any damn fool could be an intellectual.”

* * *

Markham, P. 23: “…they called it that, never the ‘Soviet intelligence service’ or ‘the KGB,’ because in Brewster’s opinion there as no such thing as the Soviet Union, only the Russian empire operating under an assumed name.”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “…never ‘the Soviet intelligence service’ or ‘the KGB,’ because in their opinion there was no such thing as the Soviet Union, only the Russian empire operating under an assumed name.”

* * *

Markham, P. 23: “The victims were doing the Russians no harm, and even if the opposite had been true, it is seldom good practice for an intelligence service to kill an enemy it knows, because the victim will only be replaced by one that it does not know…”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “The victims were doing the Russians no harm, and even if the opposite had been true, it is seldom good practice for an intelligence service to kill an enemy it knows, because the victim will only be replaced by one that it does not know.”

* * *

Markham, P. 24: “He spoke fluent Arabic and English and was an expert in small arms, explosives, and small-scale guerrilla operations. ‘The strange thing about the operation,’ Brewster had noted at the time, ‘is that all of Lazarus’s shooters and all the supporting cast are bourgeois European leftists and students.”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “He spoke fluent Arabic and English and was an expert in small arms, explosives, and small-scale guerrilla operations. ‘The strange thing about this operation,’ Horace reported, ‘is that all of Butterfly’s shooters and all the supporting cast are Palestinian Arabs or bourgeois European leftists — romantic females, in about half the cases — who sympathize with the Palestinian cause.'”

* * *

Markham, P. 25:: “Black images of hundreds of small rectangles were scattered all over the torso and legs. ‘Who took this?’ ‘We did, in Milan, while he was waiting for his bags. Those are two-ounce gold ingots, two hundred and twenty…”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “Black images of hundreds of small rectangles were scattered all over the torso and legs. ‘Who took this?’ Yeho asked. ‘We did, in Milan, while he was waiting for his bags. Those are two-ounce gold ingots, two hundred and twenty of them…'”

* * *

Markham, P. 25: “Lazarus’s mission had been to create an asylum full of lunatics, and then unlock the doors and let them go. He was going to give them twenty-eight pounds of gold and a million dollars in currency, tell them they could kill anyone they wanted to kill anyone…”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “Butterfly’s mission had been to create an asylum full of lunatics, and then unlock the doors and let them go. He was going to give them twenty-eight pounds of gold and a million dollars in currency, tell them they could kill anyone they…”

* * *

Markham, P. 26: “Brewster gazed at Chase for several seconds in great seriousness — taking a quiet amount of pride in his creation. Then he threw back his head and laughed. ‘I was right, by golly,’ Brewster said.”

From Charles McCarry, Second Sight: “The OG gazed at him for several seconds in great seriousness. Then he threw back his head and laughed. ‘I was right, by golly,’ he said.”

* * *

Markham, P. 26: “An odd nickname for the elegant, tall, and very efficient and liberated young lady with a taste for cocktail dresses and thigh-high boots. After a slightly shaky start, Chase and Frankie had become close friends and what she liked to call ‘occasional lovers.'”

From John Gardner, Special Services: “An apt nickname for the elegant, tall, and very efficient and liberated young lady. After a slightly shaky start, Bond and Q’ute had become friends and what she liked to call ‘occasional lovers.'”

* * *

Markham, P. 26: “In the past, he had often found himself bored by the earnest young men who inhabited the workshops and testing areas of G Branch, but the times were changing. Within a week of her arrival, Frnakie had become the target of many seductive attempts by unmarried officers of all ages. Chase had noticed her, and heard the reports. Word was the colder side of Frankie’s personality was uppermost in her off-duty hours.”

From John Gardner, License Renewed: “In the past, he had often found himself bored by the earnest young men who inhabited the workshops and testing areas of Q Branch, but times were changing. Within a week of her arrival, Q Branch had accorded its new executive the nickname of Q’ute, for even in so short a time she had become the target of many seductive attempts by unmarried officers of all ages. Bond had noticed her, and heard the reports. Word was that the colder side of Q’ute’s personality was uppermost in her off-duty hours.”

* * *

Markham, P. 27: “This consisted of a leather suitcase together with a similarly designed, steel-strengthened briefcase. Both items contained cunningly devised compartments, secret and well-nigh undetectable, built to house a whole range of electronic….”

From John Gardner, License Renewed: “This consisted of a leather suitcase together with a similarly designed, steel-strengthened briefcase. Both items contained cunningly devised compartments, secret and well-nigh undetectable, built to house a whole range of electronic…”

* * *

Markham, P. 28: “The large, circular smoked glass table which formed a focal point at the center of the room seemed to sink into the carpet, and from there came the sound of splashing water as it gleamed with light to become a small pond with a fountain playing at its center.”

From John Gardner, License Renewed: “The large, circular, smoked glass table which formed a focal point at the center of the room seemed to sink into the carpet, and from it there came the sound of splashing water as it gleamed with light to become a small pond with a fountain playing at its center.”

* * *

Markham, P. 28: “Then he saw her, behind the fountain, a small light dim but growing to illuminate her as she stood naked but for a thin, translucent nightdress; her hair undone and falling to her waist — hair and the thin material moving and blowing as though caught in a silent zephyr.”

From John Gardner, License Renewed: “Then he saw her, behind the fountain, a small light, dim but growing to illuminate her as she stood naked but for a thin, translucent nightdress; her hair undone and falling to her waist — hair and the thin material moving and blowing as though caught in a silent zephyr.”

* * *

Markham, P. 29:: “They made love with a disturbing wildness, as though time was running out for both of them. The draining of their bodies left the agile Frankie exhausted. She fell asleep almost immediately after their last long and tender kiss. Chase, however, stayed wide awake, thinking back to Korea…”

From John Gardner, For Special Services: “After dining at a small Italian restaurant — the Campana, in Marylebone High Street — the couple had gone back to Q’ute’s apartment, where they made love with a disturbing wildness, as though time was running out for both of them. The draining of their bodies left the agile Q’ute exhausted. She fell asleep almost immediately after their last long and tender kiss. Bond, however, stayed wide-awake, his alert state of mind brought about by…”

* * *

Markham, P. 32: “Certainly, they’d seen changes in each other in the fifteen years since then, but the changes were physical. Their minds were as they had always been. Brewster believed in intellect as a force in the world and understood that it could be used only in secret. Chase knew, because he had spent his life doing it, that it was possible to break open the human experience and find the dry truth hidden at its center. Their work had taught them both that the truth, once discovered, was usually of little use; men denied what they had done, forgot what they had believed, and made the same mistakes over and over again. Brewster and Chase were valuable because they had learned how to predict and use the mistakes of others.”

From Charles McCarry, The Tears of Autumn: “Patchen and Christopher saw changes in one another, but the changes were physical. Their minds were as they had always been. They believed in intellect as a force in the world and understood that it could be used only in secret. They knew, because they spent their lives doing it, that it was possible to break open the human experience and find the dry truth hidden at its center. Their work had taught them that the truth, once discovered, was usually of little use: men denied what they had done, forgot what they had believed, and made the same mistakes over and over again. Patchen and Christopher were valuable because they had learned how to predict and use the mistakes of others.”

* * *

Markham, P. 32: “They fought as they did, caring nothing about dying, because it seemed obvious to them that dying was the natural consequence of charging an American machine-gun position. Their bravery was an alien form of intelligence, dazzling but incomprehensible.”

From Charles McCarry, The Last Supper: “They fought as they did, caring nothing about dying, because it seemed obvious to them that dying was the natural consequence of charging a machine-gun position. Their bravery was an alien form of intelligence, dazzling but incomprehensible.”

* * *

Markham, P. 33: “Chase had never for a moment been blessed with the illusion that he was dead. He had known, touching the muzzle of the Bren with his swollen tongue, that he had not pulled the trigger. He realized, at the moment in which he felt the pain of the blow, that a Korean soldier had crept up…”

From Charles McCarry, The Last Supper: “Wolkowicz had never for a moment been blessed with the illusion that he was dead. He had known, touching the muzzle of the BAR with his swollen tongue, that he had not pulled the trigger. He realized, at the moment in which he felt the pain of the blow, that a Japanese soldier had crept up…”

* * *

Markham, P. 34: “He had a facial twitch; his cheek moved, causing the right eye to open like a caged owl’s. Chase had never seen an Asian with such an affection.”

From Charles McCarry, The Tears of Autumn: “He had a facial twitch; his cheek moved, causing the right eye to open and close like a caged owl’s. Christopher had never seen an Oriental with such an affliction.”

* * *

Markham, P. 34: “Only the table lamp, fitted with a brilliant photographic bulb, was burning. Colonel Zhao stood behind the lamp in the shadows. He removed a large hypodermic syringe from a leather case, and holding his hands in the light, filled it with an ampoule of yellow liquid.”

From Charles McCarry, The Tears of Autumn: “Now only the table lamp, fitted with a brilliant photographic bulb, was burning. Christopher stood behind the lamp in the shadows. He removed a large hypodermic syringe from the leather case, and holding his hands in the light, filled it with an ampule of yellow liquid.”

* * *

Markham, P. 34-35: “Chase sat with one flaccid leg wrapped around the other; his body shook and he wedged his hands between his crossed legs. ‘I want you to understand your situation. It’s possible for you to remain in this room indefinitely. Conditions will not change, except to get worse. No one will find you.’ Chase stopped trying to control his shivering. ‘They’ll find me,’ he said, ‘and when they do, you bastards…'”

From Charles McCarry, The Tears of Autumn: “Pigeon sat with one flaccid leg wrapped around the other; his body shook and he wedged his hands between his crossed legs. ‘I want you to understand your situation,’ Christopher said. ‘It’s possible for you to remain in this room indefinitely. Conditions will not change, except to get worse. No one will find you.’ Pigeon had stopped trying to control his shivering. ‘They’ll find me,’ he said, ‘and when they do, you bastard…'”

* * *

And that’s only through Page 17 35. As of Tuesday afternoon, I will have to put my investigations on hold due to several previously scheduled appointments. But I will carry on with my studies upon my return.

11/8/11 PM UPDATE: I have updated through Page 27.

11/8/11 PM UPDATE 2: Jeremy Duns, who did a Q&A with Markham and blurbed the book, offers his apologia.

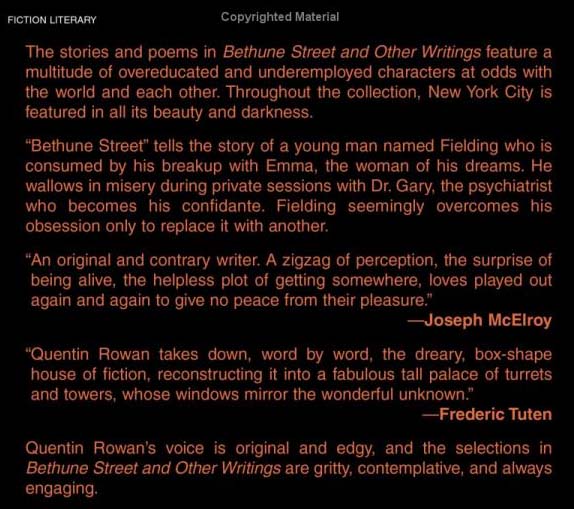

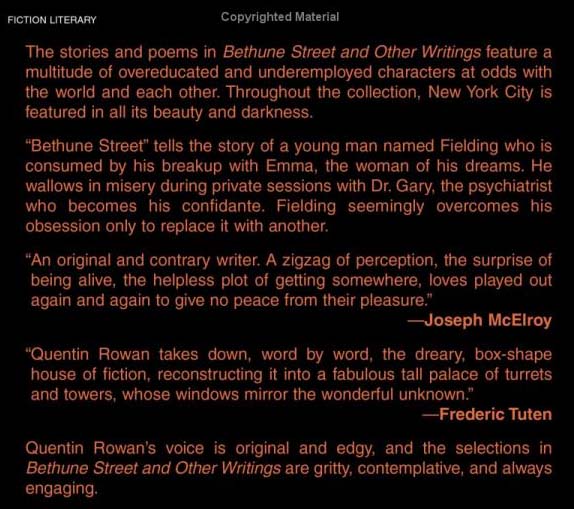

11/8/11 PM UPDATE 3: It gets worse. Quentin Rowan (aka Q.R. Markham) also managed to dupe The Paris Review. In the Spring 2002 issue (No. 161), The Paris Review published “Bethune Street,” which featured this passage:

Time gives poetry to a battlefield, or some equivalent modern-day gathering at the rim of the awful, and perhaps these St. Luke’s girls were like little flowers on an old rampart where an attack had been repulsed with heavy loss many years ago.

And here is a passage from Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana:

Time gives poetry to a battlefield, and perhaps Milly resembled a little the flower on an old rampart where an attack had been repulsed with heavy loss many years ago.

11/8/11 PM UPDATE 4: A tip from Sarah Weinman. Rowan also lifted passages in this story “Excellence” — which appeared in the Autumn 2003 issue of BOMB Magazine. Rowan’s passage:

There was a laboratory at Tembleke where a human brain was kept alive in breathwater. It was in a wooden cabinet like an old Frigidaire. I was taken by Provost Man to see it during those days and I wanted to ask questions about it — does it feel, think?

This text was lifted from Nicholas Mosley’s Accident:

There is a laboratory in Oxford where a human brain is kept alive. It is in a wooden cabinet like an old frigidaire. I was taken to see it during these days and I wanted to ask questions about it — does it feel, think.

11/8/11 PM UPDATE 5: Here’s a screenshot of blurbs from Joseph McElroy (“an original and contrary writer”) and Frederic Tuten (“Quentin Rowan takes down, word by word, the dreary, box-shape house of fiction…”) from the back flap of Bethune Street and Other Writings, which attest to Quentin Rowan’s “originality.” Note how Rowan is quick to describe himself as “original and edgy.”

11/8/11 PM UPDATE 6: More Quentin Rowan plagiarism. In this apparent essay on Erskine Childers’s The Riddle of the Sands, Rowan has lifted the whole thing from Ralph Harper’s The World of the Thriller. Here’s one small sample.

Rowan: “I have never found the same mixture of sickness and menace in Cold War novels. The rational crime, to use Camus’ term, does not frighten me in the same way as the sick crime. Many of the earliest spy stories still seem the best, and lately I’ve been fascinated by Erskine Childers’ The Riddle of the Sands.”

Harper: “I have never found the same mixture of sickness and menace in cold war novels. The rational crime, to use Camus’ term, does not frighten me in the same way as the sick crime. The early spy stories still seem the best, except for John Le Carre’s; but then he is a very fine writer.”

11/9/11 AM UPDATE: The Guardian‘s Alison Flood reports on the Markham fallout on the other side of the Atlantic. Assassin of Secrets has now been pulled in the UK.

11/9/11 AM UPDATE 2: This morning, The Huffington Post reported:

Sure enough, we see Markham lifting again for “9 Ways That Spy Novels Made Me a Better Bookseller”.

Rowan: “A spy was calm and had a faintly sardonic smile, like Alec Guinness playing George Smiley or Sean Connery eyeing Claudine Auger. A spy might be kind, but in an offhand way as if he were humoring you. Just as – as a bookstore clerk – I find myself talking to customers as if they were children, the spy has no time for your trivial concept of what is real and what isn’t.”

Lifted from Geoffrey O’Brien’s Dream Time: “A spaceman was calm and had a faintly sardonic smile, like Basil Rathbone playing Sherlock Holmes. A spaceman might be kind, but in an offhand way as if he were humoring you. Talking to you like a kid, with your trivial concept of what is real and what isn’t.”

11/9/11 AM UPDATE 3: List updated through Page 35.

11/9/11 AM UPDATE 4: Duane Swierczynski, who blurbed the Markham book, weighs in: “The whole affair leaves me feeling embarrassed, puzzled, and more than a little angry.”

11/11/11 UPDATE: In the comments section at Jeremy Duns’s blog, Duns has revealed that Quentin Rowan responded by email to his request for an apology:

Dear Jeremy,

My apologies for not making an apology sooner. People have told me to wait on writing anyone because I may still be in shock. Also, I just thought I ought to wait for a little perspective to come. I can see how angry you are and know that I deserve every bit of it and more. I promise you that the inside of my head is not a pretty place right now and i am not sitting somewhere enjoying this or laughing about it. There is nothing anyone can say that could make me feel worse than I already do. I am so sorry that I ever got you involved in this mess and would really like to try to explain it all to you. I just can’t do that if you are going to print it or tweet it (for legal reasons etc.) But if we can talk off the record, I will call you back or send a written explanation and fuller letter of apology. Once again, I am truly and deeply sorry, and still remain a great admirer of your work.

With deepest regrets,

Q

This is the first and only known Markham statement after he was unmasked as a plagiarist.

11/15/11 UPDATE: This morning, CBC Radio’s Q was kind enough to have me on their program. I hope to have audio in a bit (I’m typing this while stealing wi-fi), but I wanted to follow up on one question that the excellent Jian Ghomeshi asked me and which I failed to offer a suitable answer for. Jian asked me why wholesale plagiarism of the Rowan variety was wrong. And I offered a rather bizarre lemonade stand metaphor, describing a hypothetical scenario in which a parentless man stole somebody else’s kid, parked that kid in front of the lemonade stand and claimed it as his own, while pocketing all the revenue. Jian then asked me specifically why this was wrong. And I responded something to the effect of “I just feel that it’s wrong.” What I meant to say plainly beyond metaphor — and perhaps I was too dazzled by Jian’s impressive interviewing kung-fu to do so — is that Duchamp’s “Fountain” and Lethem’s “The Ecstasy of Influence” involve clear and traceable sources and thus, in my view, constitute enough transformation of the original sources to become art. I am with Danger Mouse on The Grey Album and with the Random House-cleared edition (that is, sources in the back) of David Shields’s Reality Hunger. In the case of Rowan, he’s essentially stealing labor from other writers in the manner of a robber baron and sharing neither revenue nor credit. And because writers are already underpaid and working long hours for their sentences, I feel this is an especially egregious stance against creative art and creative labor.

11/30/11 UPDATE: The Fix has published an essay by Rowan called “Confessions of a Plagiarist.” While Rowan has not lifted any passages for this piece, it is interesting that he has not apologized, stated plainly that he was wrong, or otherwise offered any form of contrition. He’s getting hammered in the comments.

2/14/12 UPDATE: The New Yorker‘s Lizzie Widdicombe wrote at length about Rowan and was kind enough to include Jeremy Duns and me in her very interesting piece.

Markham, Page 15: “The machine measured their breathing, the sweat on their palms, their blood pressure and pulse, and it knew whether they had stolen money from the government, submitted to homosexual advances, been doubled by the opposition, committed adultery. The test was called the ‘flutter.'”

Markham, Page 15: “The machine measured their breathing, the sweat on their palms, their blood pressure and pulse, and it knew whether they had stolen money from the government, submitted to homosexual advances, been doubled by the opposition, committed adultery. The test was called the ‘flutter.'”