Seven Years of Google Books: The Next Chapter

Presenter: James Crawford, Engineering Director, Google Books

On Thursday morning, a crowd of forty, sprouting into about seventy as the aspirin and hangover cures kicked in, listened to a engineer with a Spartan mien. Like many crunchers from Mountain View, James Crawford had the warmth and physique of an Eames lounge chair. He liked to explain things. He was confident he knew all the answers. He did, after all, work at Google.

“Google’s mission was and continues to be to organize information and make it accessible,” said Crawford early in his run. There were many sentences phrased like that. Had I known Crawford was going to speak like this, I would never have imbibed so much gratis scotch the night before.

The sense I got was that Crawford had delivered this speech many times. He ran down the stats. More than 15 million books had been scanned. That’s over 5 billion pages and 2 trillion words in 478 languages (including three books in Klingon, 82 titles in Kalaallisut, and none in Kutenal), with the earliest going back to 1473. Library partners include Stanford and the University of Michigan.

“For a lot of these books, we can simply chop off the spine and scan the pages.” For a moment, I feared that Crawford was some digital Robespierre who had recently discovered the guillotine. But I was reassured when Crawford pointed out that Google was “required to scan nondestructively.” Thank goodness for libraries and their preservation policies. To accomplish this scanning, Google holds the books down with cradles. The images are then put “through fairly sophisticated series of image algorithms,” with the curve of the pages flattened through software. Every word on the page is indexed. There is also a system of ranking algorithms to ensure, for example, that the right Hamlet rises to the top.

Crawford pointed out a “cluster problem” with the metadata. If you go to the Library of Congress, The Fellowship of the Ring (listed this way in Books in Print) will be listed as “Lord of the Rings, Vol. 1.” And J.R.R. Tolkien will be listed as “John Ronald Reuel Tolkien.”

But the biggest problem was, by far, digital rights. There are three million books in the public domain: those published before 1928. “So they’re not exactly the latest and greatest pageturners,” said Crawford, who revealed himself with such statements to be more interested in digitizing books rather than reading them. Less than a million books have clear ownership. Two and a half million books are available though partnership programs with publishers. “And then there’s all the rest in the middle: out of print but under copyright.”

The Google eBookstore, launched in December, aims to fix some of these problems. “We view the ebook as a thing you purchased,” said Crawford. “Once you’ve bought it, we feel you should read it on any device.” But what about the device known as the printed book? Crawford didn’t mention this. He was on a roll.

“We have the only really serious web reader in the business,” boasted Crawford. And it suddenly occurred to me that Crawford was referring to these Google tools as “an ebook ecosystem.” This seemed a bit Napoleonic to me, almost like insisting that one automobile plant was singlehandedly responsible for the car industry.

Crawford also brought up Google Cloud Sync, which collected a surprising amount of personal information. “We have in the cloud both the content of the book and we store the databases of what people have bought and what pages you are reading on.” In other words, if you shop at Google, they know all the books that you’ve bought. Crawford didn’t specify the degree to which this information is shared to other vendors. But he did point out that retailers had much of this intel at their disposal.

I was also troubled by Google’s tendency to dictate to the market what it wanted. “We want to help the independent bookstores do well in the digital age and not be hurt by digital.” Now I happen to share Google’s view that bringing in independent bookstores into its eBookstore is one method of preserving independent business. On the other hand, why should Google decide what’s right? Isn’t that the job of the FTC or an antitrust legislator? And what’s not to suggest that the Google eBookstore could prove harmful towards independent bookstores? On Tuesday, Tom Turvey — another Google Books representative — had said that he had “some of his best engineers working” on the experience of replicating a bookstore. Google may say that they are trying to help the indies now. But what’s to stop them from changing their policy if the books market shifts direction? This affiliate program for this is presently invitation only, but there are plans to open it up.

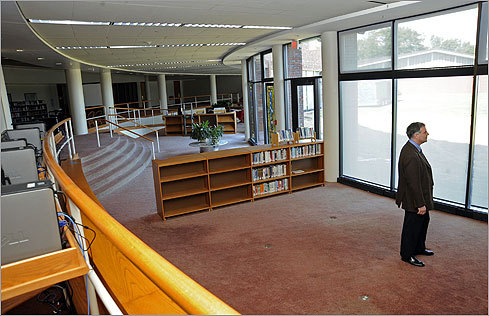

Crawford also revealed how libraries, faced with limited budgets, had relied on Google’s viewer for electronic versions of books. “They can take our viewer and put it on their website.” I don’t think it occurred to many in the crowd that commingling public and private resources may not necessarily be the most ethical solution. Wasn’t it vaguely predatory? Such questions had led the European Union to develop Europeana.

Crawford pointed out that many books published in the 16th and the 17th century were now available through Google in full color. But I was dubious when he said, “You can see them as if you’re the librarian.” Until we are able to touch these tomes, this statement will never be true. When Crawford brought up L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, observing “there are all these chapters that didn’t make it into the movie,” it was evident that he was on boilerplate and had not tailored his speech too much for the publishing crowd.

Google had recently signed an agreement with Hachette to work together on out-of-print titles in France. This would be the model for further uplift contracts. Google had also been experimenting with maps for books. Crawford brought up this interactive map for Around the World in Eighty Days. Google Books has also been used to chart how irregular verbs turn regular over time (e.g., “spoilt” transforming into “spoiled”) and, of course, the infamous Ngram Viewer, in which you can (for example) compare “The United States is” against “The United States are” over the course of time. But Crawford was disingenuous when he suggested that the dropoff of books referencing the start of a decade (as seen through the Ngram viewer) demonstrated “scientifically” that memories are getting shorter. Before making such a statement, one must account for the number of books published over the years, the speed of life in 1900 vs. the speed of life in subsequent decades, and any number of independent variables. Unfortunately, that kind of rigorous consideration isn’t always compatible with a slick Powerpoint presentation that must be delivered in nanoseconds.

Crawford also had a rather naive faith in international titles. One of his slides championed how “cross-boarder [sic] sales increased access to content,” but didn’t account for the territorial restrictions that Andrew Savikas and Evan Schnittman duked it out over on Tuesday. “As long as the publisher has worldwide rights,” said Crawford, “they should be able to move around the world.” Right. As long as I wake up tomorrow with wings on my back, I’ll be able to fly. In other words, that qualifier was a big if. If this was the type of vision that Google Books was promulgating, I wondered if Crawford’s work was clunkier and less state of the art than he realized.