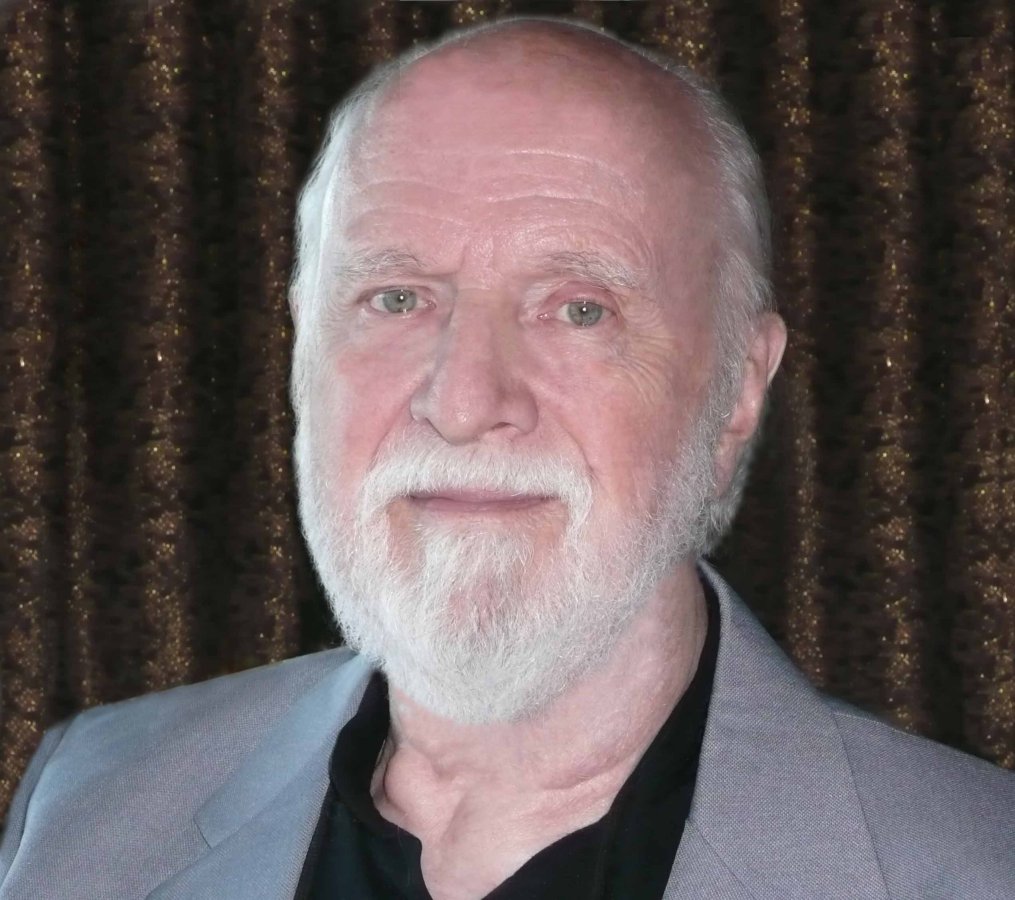

On Sunday morning, Philip Seymour Hoffman was found dead in his New York apartment. He was the victim of an apparent heroin overdose. The New York Police Department found a syringe sticking out of his arm. He was only 46.

Hoffman was a rara avis: an energetic and unforgettable vessel of thespic truth that comes once in a generation, if not every two. His dramatic range was as wide and as variegated as such indelible character actors as Paul Muni, John Cazale, or Lon Chaney Jr. You could watch three minutes of any Hoffman performance, even when he was cast in a mediocre movie, and learn six new things about acting. Hoffman’s smartest directors often imbued this great and irreplaceable performer with some physical limitation. In Charlie Wilson’s War, Mike Nichols put Hoffman behind glasses, dyed hair, and a mustache and Hoffman’s body moved inward, almost of its own will. One of his most memorable early performances was in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Hard Eight, a scene in which Hoffman is situated behind a craps table for three minutes, and the force of nature that emerged when Hoffman ferociously fired up a cigarette or addressed his audience simply could not be contained as he stood coiled in the same place.

The man never gave a boring or derivative performance. He could swing from Lester Bangs’s cautious idealism in Almost Famous, masticating ever so slightly while addressing the young music journalist as if his own convictions were malleable, to vampiric addiction in Owning Mahowny, always keeping his head down in shame and his arms scooping up sad racks of chips with the routine need of a man who knows nothing else. He played heroes, losers, villains, and psychotics, but he used the titanic force of his charisma to demand that we peer inside men we would otherwise avoid. In this sense and many more, Philip Seymour Hoffman was a true artist.

He walked on the stage and screen as if he had a thousand souls trapped inside him, all screaming to come out. Yet he was also fighting a chronic drug addition. There were reports last year of Hoffman falling off the wagon and entering rehab. It is truly tragic that drugs got him in the end.

We may never know the true totality of Hoffman’s demons, or what Hoffman had to sacrifice to give us his electric performances. It seems vulgar to probe further, even as any cursory flip through his cinematic performances reveals that they were all great, not a dud among them.

The loss of a talent as huge as Philip Seymour Hoffman feels like a referendum on American culture: a baleful strike against the waning truth and intelligence increasingly in short supply within our motion pictures. You could find the people that Hoffman played all across America, yet neither time nor place could contain this giant. Philip Seymour Hoffman will not be easily forgotten.