This is a running list of the books I’ve read in 2021 (I will update this over the course of the year):

1. Anka Radakovich, The Wild Girls Club

2. Pat Barker, Regeneration

3. Jane L. Mansbridge, Why We Lost the ERA

4. Michael Azzarad, Our Band Could Be Your Life

5. Renee Rosen, White Collar Girl

6. Anthony Haden-Guest, Studio 54, Disco, and the Culture of the Night

7. Jon Savage, England’s Dreaming

8. V.S. Naipaul, A House for Mr. Biswas

9. Siegfried Sassoon, Memoirs of an Infantry Officer

10. J.G. Ballard, Running Wild

11. J.G. Ballard, Empire of the Sun

12. Elaine Showalter, The Female Malady

13. Flannery O’Connor, The Complete Stories

14. Tim Lawrence, Love Saves the Day

15. Shirley Jackson, The Road Through the Wall

16. Martin Amis, Inside Story

17. Souvankham Thammavongsa, How to Pronounce Knife

18. Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory

19. Bryan Washington, Memorial

20. J.G. Ballard, The Kindness of Women

21. Rebecca West, The Return of the Soldier

22. Harvard Sitkoff, A New Deal for Blacks

23. Robert S. McElvaine, The Great Depression

24. Yaa Gyasi, Transcendent Kingdom

25. Sophie Ward, Love and Other Thought Experiments

26. Amity Shlaes, The Forgotten Man

27. Lynn Steger Strong, Want

28. Raven Leilani, Luster

29. J.G. Ballard, Concrete Island

30. Shirley Jackson, Hangsaman

31. Sylvia Plath, The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath

32. Rachel Devlin, Relative Intimacy

33. Shirley Jackson, The Bird’s Nest

34. Rumaan Alam, Leave the World Behind

35. Mariko Tamaki, Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up with Me

36. Gabrielle Bell, Inappropriate

37. J.G. Ballard, Hello America

38. J.G. Ballad, Millennium People

39. Adam Levin, Hot Pink

40. Catharine Arnold, Pandemic 1918

41. Matt Fraction, Big Hard Sex Criminals Volume 2

42. Bob Rosenthal, Cleaning Up New York

43. Gay Talese, Thy Neighbor’s Wife

44. J.G. Ballard, The Unlimited Dream Company

45. Richard Ford, Let Me Be Frank with You

46. The Best American Short Stories 2020

47. Vera Brittain, Testament of Youth

48. Lydia Millet, Omnivores

49. Peter Shapiro, Turn the Beat Around

50. Lydia Millet, George Bush, Dark Prince of Love

51. Don DeLillo, Great Jones Street

52. Lydia Millet, My Happy Life

53. China Mieville, October

54. Danielle Evans, The Office of Historical Corrections

55. Italo Calvino, The Baron in the Trees

56. Lydia Millet, Everyone Pretty

57. [Literary biography, title omitted for moral reasons]

58. Alison Bechdel, The Secret to Superhuman Strength

59. Jack Kerouac, The Dharma Bums

60. Tim O’Brien, Going After Cacciato

61. Lysley Tenorio, The Son of Good Fortune

62. Lydia Millet, How the Dead Dream

63. Tim O’Brien, If I Died in a Combat Zone

64. Tim O’Brien, Northern Lights

65. Nelson George, The Death of Rhythm and Blues

66. Richard Ford, Sorry for Your Trouble

67. Nelson George, Hip Hop America

68. Ernest R. May, The World War & American Isolation 1914-1917

69. Kazuo Ishiguro, Klara and the Sun

70. Tim O’Brien, The Nuclear Age

71. Lydia Millet, Love in Infant Monkeys

72. Richard Wright, Black Boy

73. Gay Talese, The Bridge

74. Lydia Millet, Ghost Lights

75. Gay Talese, Fame and Obscurity

76. Gay Talese, The Over Reachers

77. John D’Emilo and Estelle B. Freedman, Intimate Matters

78. Richard Wright, The Outsider

79. Richard Russo, Trajectory

80. Tim O’Brien, The Things They Carried

81. Jonathan Ames, A Man Named Doll

82. Gay Talese, Honor Thy Father

83. Lydia Millet, Magnificence

84. Alex Espinoza, Cruising

85. Mary Helen Washington, The Other Blacklist

86. Nelson George, Post-Soul Nation

87. J.G. Ballard, Rushing to Paradise

88. Darin Strauss, The Queen of Tuesday

89. Brett Harvey, The Fifties

90. Gayle E. Pitman, The Stonewall Riots: Coming Out in the Streets

91. Richard Russo, The Destiny Thief

92. Duncan Hannah, Twentieth Century Boy

93. Tove Ditlevsen, The Copenhagen Trilogy

94. Richard Russo, Everybody’s Fool

95. Langston Hughes, Not Without Laughter

96. Matt Fraction, Sex Criminals #5

97. Matt Fraction, Sex Criminals #6

98. Tim O’Brien, In the Lake of the Woods

99. Richard Wright, The Man Who Lived Underground

100. George Scuhlyer, Black No More

101. Paul Wilson, Center Square: The Paul Lynde Story

102. Ishamel Reed, The Terrible Twos

103. Rudolph Fisher, The Conjure-Man Dies

104. Lydia Davis, The Complete Short Stories of Lydia Davis

105. Ann Quin, Berg

106. Arna Bontremps, Black Thunder

107. A. Scott Berg, World War I and America

108. J.G. Ballard, Kingdom Come

109. Anna Kavan, I Am Lazarus

110. Joshua Cohen, The Netanyahus

111. Joshua Cohen, Four New Messages

112. Anna Kavin, Ice

113. Allan Berube, Coming Out Under Fire

114. Anna Kavan, Machines in the Head

115. Irwin Shaw, Five Decades

116. Ishamel Reed, Juice!

117. Martin Duberman, Stonewall

118. Lisa Wade, American Hookup

119. Moa Romanova, Goblin Girl

120. Ana Quin, Passages

121. Ishamael Reed, Mumbo Jumbo

122. Ben Passmore, Sports is Hell

123. Adrian Tomine, The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist

124. Darin Strauss, Half a Life

125. Adrian Tomine, Killing and Dying

126. Anna Kavan, A Charmed Circle

127. Ishmael Reed, The Last Days of Louisiana Red

128. Joshua Cohen, Moving Kings

129. Ishmael Reed, Yellow Back Radio Brokedown

130. Ishamel Reed, Reckless Eyeballing

131. Anna Kavin, The Parson

132. Ishmael Reed, Flight to Canada

133. Ishmael Reed, The Freelance Pallbearers

134. Ishmael Reed, The Terrible Threes

135. Elizabeth Cobbs, The Hello Girls

136. Matt Fraction, Who Killed Jimmy Olsen?

137. Lindy West, Shit, Actually

138. Lauren Oyler, Fake Accounts

139. William T. Vollmann, No Immediate Danger

140. Ishmael Reed, Japanese by Spring

141. Patricia Lockwood, No One is Talking About This

142. Kristen Radtke, Seek You

(Image: Creative Commons via benuski)

It is easy to forget, as brave women

It is easy to forget, as brave women

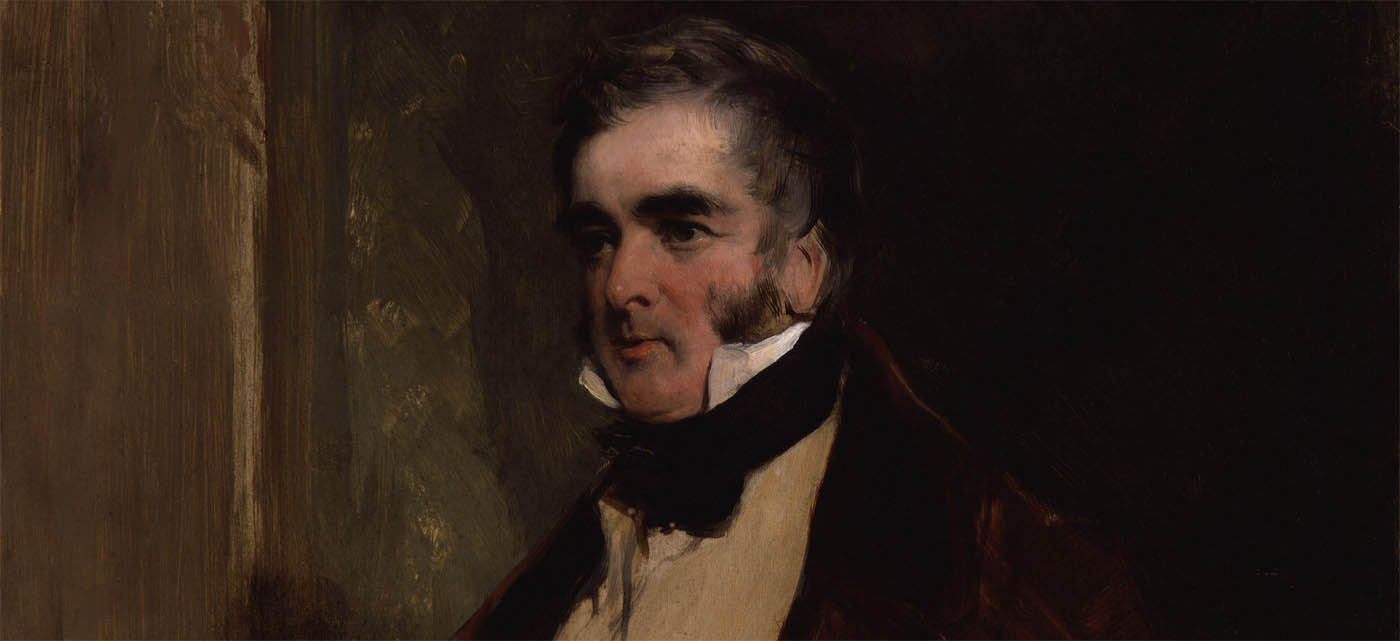

History has produced such a rich pile of devious political figures who spend every spare minute scheming and plotting their rise that today’s aspiring aristocrats, who can be found working every connection to get their kids into bright educational citadels and reliable sinecures, cannot come close to such cutthroat monomania. Yet there are also those who blunder into top office like bumpkins crashing high-class weddings through the simple repetitive act of placing one foot in front the other. William Lamb, aka Lord Melbourne, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom for eight years (1834, 1835-1841) and the subject of Lord David Cecil’s generous biography, was one such man.

History has produced such a rich pile of devious political figures who spend every spare minute scheming and plotting their rise that today’s aspiring aristocrats, who can be found working every connection to get their kids into bright educational citadels and reliable sinecures, cannot come close to such cutthroat monomania. Yet there are also those who blunder into top office like bumpkins crashing high-class weddings through the simple repetitive act of placing one foot in front the other. William Lamb, aka Lord Melbourne, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom for eight years (1834, 1835-1841) and the subject of Lord David Cecil’s generous biography, was one such man.

Three years ago, my jocular compadre Lydia Kiesling

Three years ago, my jocular compadre Lydia Kiesling